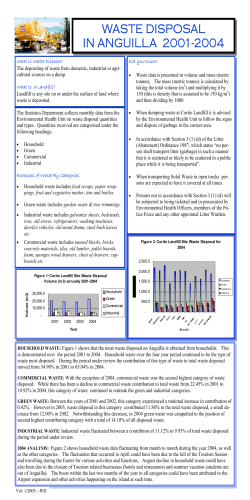

INTEGRATED MUNICIPAL SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT