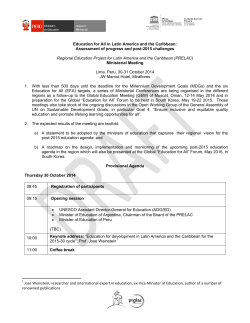

The Post-2015 Agenda â Delivering its Core Promises to Children