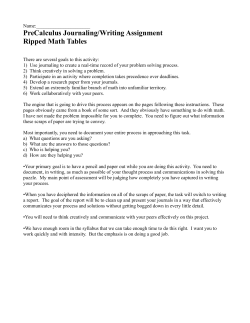

Single-Column Edition