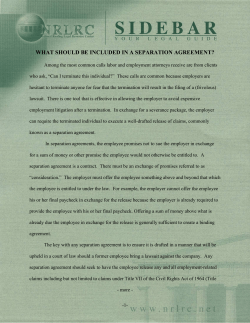

View PDF - Columbia Law Review