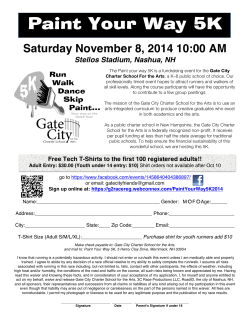

Document