human sustainable development - NASC Document Management

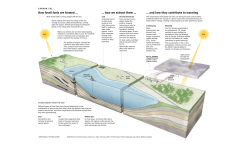

HUMAN SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT: GLOBAL ISSUES Trilochan Pokharel Deputy Director of Studies Nepal Administrative Staff College tpokharel@nasc.org.np Abstract Sustainable development is widely researched and written discipline of the new millennium. Defined in Brundtland conference in 1987 as meeting present needs without compromising the ability to satisfy future need attracted attention for a balance between environmental sustainability and development activities. A progressive definition that emerged these days argues sustainability needs to have convergence with human development. Therefore, it proposes clear arguments of distinction between the ‘to be sustained’ and ‘to be developed’. This study elucidates some fundamental assumptions and gaps between sustainability and human development based on the country level data from 187 countries on human development and environmental aspects. First, there is imbalance between use of natural resources and level of development. This sustains the arguments of that developed countries are exploiting natural resources and also threatening the sustainability by increasing carbon dioxide emissions, a major pollutant posing pressure on global climate change. Second, developing countries are the direct victim of global environmental degradation. The human cost of degradation is several times higher in developing countries who already are marred by poverty and poor governance structure. 1. Introduction It has been many years that we have started discussing about development. Several useful theories, indicators and methods have been devised to explain and measure development. Recent approaches are human development and sustainable development. These two concepts basically argue to consider development to a broader perspective rather than a mere concept of economic growth. Much have been written and discussed about these issues ever since their evolution. These approaches have worked good to redefine development to a newer concept but need further revision in addressing the issues of sustainability of development (Ross, 2009). Human sustainable development involves two important concept together- human development and sustainable development. This is an approach used to produce a better understanding and promoting sustainable development with human face. Human development and sustainable development if considered independently may have shortcomings of disciplinary limitations. To have a common understanding and reinforcing each-other, it is better to bring these two approaches together. A classical human development index has limitation to explain the environmental cost of the development (Neumayer, 2001). It basically ranks countries based on health, education and access to income. Countries are criticized for not maintaining environmental balance against the progress in human development (United Nations Development Programme [UNDP], 2014), allowing rooms to criticize for shortage of not addressing environmental concerns adequately (Bravo, 2014). The criticisms are simple but carry worth Paper presented in 13th South Asia Management Forum, 26-27 March 2015, Colombo, Sri Lanka considerations. An appealing question is whether countries with high development indicators are doing justice with environment (Mazilu & Guirgea, 2011). The contradictions of the recent development phenomena concern on the ‘growing wealth but, at the same time, growing environmental degradation’ (Melamed & Paul, 2013). Defined by Brundtland Commission 1987 and expanded by the Earth Summit 1992, sustainable development considers three pillars of development – economic, social and environmental growth (Soubbotina, 2004). Each pillars contains number of development indicators that must be satisfied by the countries. Despite the tremendous development achievements in the new millennium, there are contradictions abound. There are debates on the cost of development against cost of environment. Are countries able to achieve a balance between development and environmental sustainability? Who are paying for the human cost of development? What should be basis for achieving sustainability in the development? There are number of questions like this that the development discourse has to propose further. 2. Objectives This paper serves major two objectives. First, this analyses the relationship between human development and environmental factors. It helps to know the contribution of the countries to impose environmental threats. Second, it analyses the impact of environmental degradation in human lives. This analysis allows to enhance understanding the cost of environmental degradation. In addition, this paper makes a global comparison of countries in terms of relative contribution to environmental degradation and its human impact. 3. Materials and Methods This study uses data from Human Development Report 2014 for 187 countries (United Nations Development Programme [UNDP], 2014). The data used in this analysis are human development index (composite of healthy life, knowledge and decent standard of living), primary energy supply (fossil fuels, renewable sources, electrification), carbon dioxide emission, natural resources (natural resources depletion and forest area), effects of environmental threats (deaths of under 5 children due to outdoor and indoor air pollution, unsafe water, unimproved sanitation or poor hygiene and population living on degraded land) and impact of natural disasters (number of deaths and population affected). The study uses bivariate analysis methods to derive inferences. Using scatter diagrams, the relationships of human development index with environmental variables are displayed. A bivariate correlation analysis between environmental factors are and human development is done to derive conclusions. 4. Results and Analysis The relationship between development and environment is always contending. There is no straightforward relationship of environmental impact of development. Human impacts of environmental degradation imposed by developmental activities demand careful analysis. In this section, countries’ position based on the relationship between environmental factors and human development are displayed. A growing argument is the imbalance between development and 2 Paper presented in 13th South Asia Management Forum, 26-27 March 2015, Colombo, Sri Lanka impact on ecological balance. Consumption of fossil fuels is remarkably higher among the countries with higher development indicators (Figure 1). Figure 1: HDI and fossil fuels as % of total energy supply (N=134) First contradiction is that countries with high development are dependent to non-renewable resources. Countries with higher human development are also responsible for higher consumption of fossil fuels. Qatar, Kuwait, Australia, United States, United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Japan, Saudi Arabia are among the countries with more than 80 percent consumption of fossil fuels as primary energy along with high development indicators. It may imply exploitation of fossil fuels is inevitable for attending the goals of development for all countries. Such competition may pose a threat for sustainability of development. On the other hand, countries with low development also have low consumption of fossil fuels but their current consumption pattern may reject the pledge to phase out fossil-fuel subsides (Swift, Turnbull, Schmidt, & Kertzmann, 2012). Figure 2 displays the relationship between human development and carbon dioxide emissions. Countries with high development are posing enormous threat to the environment by producing huge amount of carbon dioxide. This calls for an action to redefine the development discourse. It urges for advocacy to audit environmental impact of development. Particularly countries like Qatar, Kuwait, Trinidad and Tobago, United States, Oman, Brunei, Luxemburg, Saudi Arabia and Australia are among the countries with high human development and high carbon dioxide emissions rate. Among the countries with high carbon emissions are fossil oil dependent. Basically, the countries in G20, by providing subsidies for fossil fuel exploration, ‘are directing large volume of finance into high carbon assets that cannot be exploited without catastrophic climate effects; diverting investment from economic low-carbon alternatives such as solar, wind and hydro power’ (Bast, Makhijani, Pickard, & Whitley, 2014). 3 Paper presented in 13th South Asia Management Forum, 26-27 March 2015, Colombo, Sri Lanka Figure 2: HDI and carbon dioxide emissions (tonnes) (N=186) Other side of analysis proposes an alarming message. As expected, there is strong inverse relationship between development and child survival (Figure 3). The deaths of under five children due to indoor air pollution is higher among the less developed countries. It is mainly the due to increase in pneumonia and other acute lower respiratory infections (ALRI), which accounts for 900,000 deaths out of 2 million under five deaths (World Health Organization [WHO], 2012). It is mainly because households in less developed countries depend on traditional sources of energy like firewood, crop residues, dung, straw and coals. These sources produce high level of indoor pollution causing a serious threat to the survival of children and women. Supplementing these arguments, results show that countries using less fossil fuels have higher child deaths due to indoor air pollution. Countries like Zambia, Niger, Togo, Cameroon, Tanzania and Mozambique use less than 20 percent fossil fuels as primary energy but have more than 200 under 5 child deaths per 100,000 children (Figure 4). On the other hand, countries that use large proportion of fossil fuels have low health impact on child survival. However, studies claim the health impacts of fossil fuels are inevitable (Bailey, 2011) and such impacts may transmit across the globe, particularly affecting less developed countries for the reasons they are not accountable. In addition, the projected growth in demand of energy in developing countries in the coming years may increase the health impact more seriously (McMichael, Woodward, & van Leeuwen, 1994). 4 Paper presented in 13th South Asia Management Forum, 26-27 March 2015, Colombo, Sri Lanka Figure 3: HDI and U5 death due to indoor air pollution (N=182) Could be of low level but a conclusion can be derived that in order improve in child survival, countries have to change sources energy from traditional sources to fossil fuels. Data show, consumption of fossil fuels can explain about 35 percent variation in under five mortality due to indoor air pollution (Figure 4). This evidence projects a possible struggle among developing countries for increasing dependency in non-renewable resources to attain development goals. It will be hard for the developed countries to deny the demands of developing countries. It may increase the burden in already strained environmental balance. Hence, it necessary to harmonize the relationship in human ecology (Marten, 2001) for achieving human sustainable development. Figure 4: Fossil fuels as % of primary energy and U5 death due to indoor air pollution (N=131) Child health alone is a strong indicator of countries’ socio-economic development. Higher child mortality explains multiple disadvantages of the countries in many aspects including environmental factors. Not enough has been written about the impact of high consumption of fossil fuels on child health. Perera (2008) argues ‘[c]onsideration of the full spectrum of health risks to children from fossil fuel combustion underscores the urgent need for environmental and 5 Paper presented in 13th South Asia Management Forum, 26-27 March 2015, Colombo, Sri Lanka energy policies to reduce fossil fuel dependence and maximize the health benefits to this susceptible population. We do not have to leave our children a double legacy of ill health and ecologic disaster.’ Table 1 explains the relationships among the environment and development variables. The contradictory environment and development nexus is not a new phenomenon but needs more careful and decomposed analysis. Evidences are contentious. It reinforces the argument whether we applaud the progress of developed countries at the cost of exploitation on environmental balance. A positive relationship (r=0.603, p<0.01) between human development index and consumption of fossil fuels raises question of sustainability of development. Despite having many claims for reduction in consumption, fossil fuels will remain a major source for much of the 21st century (Lincoln, 2005). But the alarming message is the increasing cost of sustainable development. It has direct impact on emission of carbon dioxide which has a positive relationship with level of development. The tradition of high emissions from the first world countries including North American and European continent has been exceeded by the Asian countries (Siddiqi, 1996) indicating a gradual shift in geography of fuel consumption. Table 1: Correlation of environmental factors with human development index (N=187) Variables Fossil fuels as % of primary energy supply Renewable sources as % of primary energy supply Carbon dioxide emissions (tonnes) Natural resource depletion Forest area as % of total land area % change in forest between 1990 to 2011 Fresh water withdrawals (% of total renewable water resources) Death rate of under five children due to outdoor air pollution Death rate of under five children due indoor air pollution Death rate of under five children due to unsafe water, unimproved sanitation or poor hygiene % of population living on degraded land Number of deaths due to natural disasters (per year per million population) Population affected due to natural disaster (per million people) Correlation value 0.603** -0.579** 0.583** -0.130 0.052 0.372** 0.146 -0.609** -0.709** -0.766** -0.454** -0.117 -0.354** ** p<0.01 Interestingly an inverse relationship of development with utilization of renewable sources of energy has given enough room to question on the sustainability of the development practices. Countries like Australia, Greece, the United States of America, Ireland, Israel, Japan, Saudi Arabia, Russia and Canada are countries with low dependency on renewable resources among others. Two Asian giants, China and India, are among the countries with less than 30 percent dependency in renewable energy. With the growing increase in demand of energy, these countries tend to exploit non-renewable resources in the coming days. Even in global estimate, 6 Paper presented in 13th South Asia Management Forum, 26-27 March 2015, Colombo, Sri Lanka the contribution of renewable energy is just around one-fifth, of which modern renewables account only 10 percent (REN21, 2014). On the other hand, human impacts of environmental degradation are huge for less developed countries. For example, deaths of children under five due to outdoor (r=-0.609, p<0.01) and indoor air pollution (r=-0.709, p<0.01) and unsafe water, unimproved sanitation or poor hygiene (r=-0.766, p<0.01) is exceptionally higher among the less developed countries. Poor countries are unable to invest in protection of human health due to environmental degradation. WHO (2015) estimates environmental hazards cause as much as 25 percent of global deaths. Of these, most of the deaths occur in developing countries and are preventable. There could be multiple disadvantages for human health due to loss in environmental standard. For example, global environmental changes like loss of bio-diversity may impose health consequences ‘by increasing instability in disease transmission in animal population, which are the source of most of the pathogens affecting humans’ (Taylor, Latham, & Woolhouse, 2001). Table 1 is also evident for large number of population from less developed countries are living on degraded land. Degraded land is characterized with decrease in land productivity or usefulness of a particular place due to human interference (Johnson & Lewis, 2007) and increasing environmental disadvantages making the survival of people dependent to those lands more difficult. There could be several reasons for land degradation. But whatever the reasons are, it mostly affects the poor and marginal rural people living worldwide disproportionately (Gisladotier & Stocking, 2005). It is unjust to argue land degradation as simply a technological problem (Levia, 1999) but is a result of complexities in the natural ecosystem and human social systems (Wrold Meteorological Organization, 2005) including development practices. Land degradation impacts indifferently but more to population depending on land for their survival (Reddy, 2003). There are projections that land degradation continues to increase with an accelerated rate aggravated by climate change and increasing extraction of land. In many developing countries increasing use of chemical fertilizers and non-degradable pollutants may pose additional threat to land quality. Land degradation and climate change have causal relationship. They reinforce the severity of impact. And the impacts are more severe to marginal population living in less developed world who cannot fight the environmental shocks. Although natural disasters do not discriminate the countries based on their level of development, the impacts greatly vary. Results of this study show people of less developed countries have higher impacts of natural disasters (r=-0.354, p<0.01). Disasters have multiple influences in socio-economic and human lives. It is not only disasters that increases vulnerability to human lives but the socio-political, economics and governance status of a country determine the human impact of disasters. There is increasing trend of climate induced disasters. Many developing countries including Nepal, India, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and the Maldives are experiencing climate induced disasters. For example, Nepal is at high risk of flood, outburst of glacial lakes, depletion of snow deposits in mountain and erratic rains. Likewise, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and the Maldives are experiencing risk with sea level rise. Countries in South Asia region have endured a series of catastrophic disasters compounding with the pains of poverty and poor performance in human development (Memon, 2012). Disaster risk is connected with the process of human sustainable development. Disasters put development at risk while development in 7 Paper presented in 13th South Asia Management Forum, 26-27 March 2015, Colombo, Sri Lanka human capacity may reduce the disaster risk (United Nations Development Programme [UNDP], 2004). The analysis shows that indicators that do not consider environmental factors are insufficient to portray a clear picture of development. Development practices must account the environmental cost for reducing the imbalance pressure in consumption of natural resources. Human sustainable development is an approach to increase the commitments of countries to consider their development activities through a sustainability perspective and maintain a standard between ‘to be developed’ and ‘to be sustained’. 5. Conclusion Sustainable development is a buzz word of this century and will keep dragging discourses for many years to come. The discourse has encouraged countries to redefine development activities from a different and broader framework. Defining development is tricky and contextual. But it is necessary to define and act on. There are enough theoretical writings on putting human face into development and ensure the sustainability of development outcomes. But the results are yet to confirm the practices. There is a trending gap in ecological balances. Since the principle of human development is to enlarging choices of people, such choices are not uniform throughout the world. The world is interdependent. None of the development and environmental issues is confined to political boundary of a country. It cuts across and beyond. Therefore, we cannot ignore the environmental impact of human activities. Anand and Sen (2000) call for not to ‘abuse and plunder our common stock of natural assets and resources leaving the future generations unable to enjoy the opportunities we take for granted today’. As ‘access to ecosystem services will become more critical factor for economic success and resilience in the 21st century’ (Ewing, et al., 2010), achieving an ecological balance is a challenge for both developed and developing countries. The trend of exploiting natural resources is shifting to developing countries including Asia and Pacific region where resource intensive production is practiced (WWF, ADB & Global Footprint Network, 2012). Despite the several commitments and improvements in technology to reduce the pressure on environment, there is continuing imposition on environment. The increasing pressure on ecological footprint has clarion call for rethinking our development activities for achieving human sustainable development. The fundamental question of meeting the gap for achieving the global target of human sustainable development without compromising the lives of developing countries is critical. It may be possible only by integrating sustainability issues in development activities and using innovation and technology to reduce strain on environmental factors. Thus, there is need to emphasize human sustainable development rather than merely focusing on development without considering the critical factors of sustainability. 6. References Anand, S., & Sen, A. (2000). Human development and economic sustainability. World Development, 28(12), 2029-2049. 8 Paper presented in 13th South Asia Management Forum, 26-27 March 2015, Colombo, Sri Lanka Bailey, D. (2011). Gasping for air: Toxin pollutants continue to make millions sick and shorten life. Natural Resource Defense Council. Retrieved January 20, 2015, from http://www.nrdc.org/health/files/airpollutionhealthimpacts.pdf Bast, E., Makhijani, S., Pickard, S., & Whitley, S. (2014). The fossil fuel bailout: G20 subsidies for oil, gas and coal exploration. London: Overseas Development Institute & Oil Change International. Retrieved January 25, 2015, from http://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odiassets/publications-opinion-files/9234.pdf Bravo, G. (2014). The Human Sustainable Development Index: New calculations and a first critical analysis. Ecological Indicators, 37, 145-150. doi:doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2013.10.020 Ewing, B., Moore, D., Goldfinger, S., Oursler, A., Reed, A., & Wackernagel, M. (2010). Ecological footprint atlas 2010. Oakland: Global Footprint Network. Gisladotier, G., & Stocking, M. (2005). Land degradation control and its global environmental benefits. Land Degrataion and Development, 16, 99-112. Johnson, D. L., & Lewis, L. A. ( 2007). Land degradation: Creation and destruction. Oxford, UK: Rowman & Littlefield. Levia, D. F. (1999). Land degradation: Why is it continuing? Ambio, 28(2), 200-201. Lincoln, S. F. (2005). Fossil fuels in the 21st century. Ambio, 34(8), 621-627. Marten, G. G. (2001). Human ecology: Basic concepts for sustainable development. London: Earthscan . Mazilu, M., & Guirgea, D. (2011). Contradiction between the human development and the necessity of implementing the sustainable development principles. Present Environment and Sustainable Development, 5(2), 241-253. McMichael, A. J., Woodward, A. J., & van Leeuwen, R. E. (1994). The impact of energy use in industrialised countries upon global population health. Medicine and Global Survival, 23-32. Melamed, C., & Paul, L. (2013). How to build sustainable development goals: integrating human development and environmental sustainability in a new global agenda. London: Overseas Development Instittute. Retrieved January 18, 2015, from http://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/8290.pdf Memon, N. (2012). Disasters in South Asia: A regional perspective. Karachi: Pakistan Institute of Labour Education and Research. Neumayer, E. (2001). The human development indexand sustainability: A constructive proposal. Ecological Economics, 39, 101-114. Retrieved January 30, 2015, from http://www.lse.ac.uk/geographyAndEnvironment/whosWho/profiles/neumayer/pdf/Article%20in %20Ecological%20Economics%20(HDI).pdf Perera, F. P. (2008). Children are likely to suffer most from our fossil fuel addiction. Environmental Health Perspectives, 116(8), 987-990. Reddy, V. R. (2003). Land degradation in India: Extent, costs and determinants. Economic and Political Weekly, 38(44), 1-7. REN21. (2014). Renewables 2014: Global status report. Paris: REN21. Retrieved February 2, 2015, from http://www.ren21.net/portals/0/documents/resources/gsr/2014/gsr2014_full%20report_low%20re s.pdf Ross, A. (2009). Modern interpretations of sustainable development. Journal of Law and Society, 36(1), 32-54. Siddiqi, T. A. (1996). Carbon dioxide emissions from the use of fossil fuels in Asia: An overview. Ambio, 25(4), 229-231. Soubbotina, T. P. (2004). Beyond economic growth: An introduction to sustainable development. Washington DC: The World Bank. Swift, A., Turnbull, D., Schmidt, J., & Kertzmann, S. (2012). Fuel facts. Natural Resource Defence Council. Retrieved Januray 24, 2015, from http://endfossilfuelsubsidies.org/files/2012/05/fossilfuelsubsidies_report-nrdc.pdf Taylor, L. H., Latham, S. M., & Woolhouse, M. E. (2001). Risk factors for human disease emergence. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of Lodon Biological Sciences, 356(1411), 983989. 9 Paper presented in 13th South Asia Management Forum, 26-27 March 2015, Colombo, Sri Lanka United Nations Development Programme [UNDP]. (2004). Reducing disaster risk: A challange for development. New York: UNDP. United Nations Development Programme [UNDP]. (2014). Human development report 2014. New York: UNDP. United Nations Development Programme [UNDP]. (2014). National human development report: Montenegro. Montenegro: UNDP. Retrieved January 25, 2015, from http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/nhdr_eng_-web.pdf WHO. (2015, February 6). Environment and health in developing countries. Retrieved from The Health and Environment Linkages Initiative: http://www.who.int/heli/risks/ehindevcoun/en/ World Health Organization [WHO]. (2012). Indoor air pollution, health and the burden of disease. Geneva: WHO. Retrieved January 27, 2015, from http://www.who.int/indoorair/info/briefing2.pdf Wrold Meteorological Organization. (2005). Climate and land degration. Geneva: World Meteorological Organization. Retrieved February 3, 2015, from http://www.wmo.int/pages/themes/wmoprod/documents/WMO989E.pdf WWF, ADB & Global Footprint Network. (2012). Ecological footprint and investment in natural capital in Asia and the Pacific. Manila: ADB. 10

© Copyright 2025