Biomedical Research Journal - April 2015 Issue - 25.04

SCHOOL OF SCIENCE

BiomedicalResearchJournal

APRIL 2015 | VOLUME 2 | ISSUE 1

pISSN: 2349-3666; eISSN: 2349-3674

SCHOOL OF SCIENCE

BiomedicalResearchJournal

APRIL 2015 | VOLUME 2 | ISSUE 1

EDITORS-IN-CHIEF

EDITORIAL BOARD

Dhananjaya Saranath (Mumbai, India)

Ali Syed Arbab (Detroit, USA)

Alpana Ray (Missouri, USA)

Aparna Khanna (Mumbai, India)

Amit Agarwal (Bangalore, India)

Anandwardhan Hardikar (Sydney, Australia)

Anjali A. Karande (Bangalore, India)

Ashok B. Vaidya (Mumbai, India)

Basuthkar J. Rao (Mumbai, India)

Dhirendra Bahadur (Mumbai, India)

SECTION EDITORS

Hemant Malhotra (Jaipur, India)

Karuna Shanker (Lucknow, India)

Cancer Biology:

Kirti S. Laddha (Mumbai, India)

Mayur Yergeri (Mumbai, India)

Girish Maru (Navi Mumbai, India)

Mohan C. Vemuri (Frederick, USA)

Naganand Rayapuram (Evry, France)

Stem Cell Biology:

Nancy Pandita (Mumbai, India)

Partha Basu (Kolkata, India)

Vaijayanti P. Kale (Pune, India)

Paul J. Verma (Rosedale, Australia)

Prasad S. Adusumilli (New York, USA)

Nanotechnology:

Pritish Bhattacharya (New Jersey, USA)

Pulok Mukherjee (Kolkata, India)

Vilas G. Gaikar (Mumbai, India)

Purvish M. Parikh (Mumbai, India)

Ramesh Goyal (Ahmedabad, India)

Phytochemistry:

Sai Yendamuri (New York, USA)

Sukhinder Kaur Cheema (St. John's, Canada)

Lokesh Bhatt (Mumbai, India)

Sumitra Chanda (Rajkot, India)

Sunita Saxena (New Delhi, India)

Surinder K. Mehta (Chandigarh, India)

Tania Fernandez (San Francisco, USA)

Victoria M. Villaflor (Chicago, USA)

EDITORIAL OFFICE

EDITORIAL ASSISTANT

School of Science, NMIMS (Deemed-to-be University)

Bhaidas Sabhagriha Building,

Bhaktivedanta Swami Marg,

Vile Parle (W), Mumbai 400056, India.

Email: brj.sos@nmims.edu

Brijesh S. (Mumbai, India)

INDEXED WITH: Google Scholar, CiteFactor, DRJI

Biomedical Research Journal

General Information

Aims and Scope

well as provide hard copy of the Journal issues

“Biomedical Research Journal (BRJ)” is a

to the authors of the papers on request.

premier peer reviewed open access journal,

published by School of Science, NMIMS

Information for Subscribers

(Deemed-to-be) University, for promoting the

BRJ is planned as a six monthly publication

advancement of ideas in the interdisciplinary

with two issues published in the first year.

realms of Medicine, Science and Technology.

Currently, there are no subscription charges for

The goal is to share new discoveries and

the journal and can be accessed online. For

translational

submission instructions, subscription and

knowledge

with

scientists,

academicians, clinicians and students in the

additional

information

field of Biomedical and Biology/Chemistry/

http://science.nmims.edu

please

visit:

Biotechnology/Stem Cell Biology/Cancer

Biology in the realm of basic and applied

Disclaimer

aspects in the different areas.

The views and opinions expressed in the

BRJ aims at creating a platform to help

articles published in the journal are the sole

advance the domains and frontiers of inter- and

responsibility of the authors. The Publisher,

multi-disciplinary research across the various

NMIMS School of Science and the Editors

areas of sciences and recent advances in cross

cannot be held responsible for errors or any

pollination across biology, chemistry, and

consequences from the use of information

medicine. Integrative science is the present

contained in this journal.

and future of science, and the journal proposes

to highlight and emphasize contemporary

Copyright

technology towards understanding various

The Journal grants all users a free, permanent,

aspects of the sciences.

worldwide, continuous right of access to, and a

The initial focus areas of BRJ include

license to copy, use, distribute, perform and

review articles and original research papers in

display the work publicly and to make and

cancer biology, stem cell biology, nano-

distribute derivative works in any digital

technology and phytochemistry.

medium for any reasonable non-commercial

A rigorous peer review process is

purpose, subject to proper citation of

implemented to judge the effectiveness,

authorship and ownership rights. The journal

legitimacy and reliability of the research

also grants the right to make a printed copy for

content. The papers will be published online as

personal non-commercial use only.

Contents

April 2015, Volume 2, Issue 1

Editorial: Precision/personalized medicine in cancer

Dhananjaya Saranath and Aparna Khanna ..........................................................................................1

Advances in omics technologies in GBM

Uday B. Maachani, Uma Shankavaram, Kevin Camphausen and Anita Tandle ..................................6

Dendrimers based electrochemical biosensors

Saumya Nigam, Sudeshna Chandra and Dhirendra Bahadur ...........................................................21

Developmental signalling in maintenance and regulation of cancer stem cells

Sweta Dash, Raghava Reddy Sunkara and Sanjeev K. Waghmare ..................................................37

Diverging role of Nrf2 in cancer progression and prevention

Lokesh Gambhir, Rahul Checker, Deepak Sharma and Santosh K. Sandur .....................................57

Physiology of embryo-endometrial cross talk

Deepak N. Modi and Pradeep Bhartiya …………………..…………….............................………….....83

Human EGFR-2, EGFR and HDAC triple-inhibitor CUDC-101 enhances

radiosensitivity of glioblastoma multiforme cells

Cody D. Schlaff, W. Tristram Arscott, Ira Gordon, Kevin A. Camphausen and Anita Tandle ............105

Phenotypic and functional characterization of a marrow-derived stromal cell

line, M210B4 and its comparison with primary marrow stromal cells

Shweta Singh, Suprita Ghode, Moirangthem Ranjita Devi, Lalita Limaye and Vaijayanti Kale ........120

Editorial

Precision/Personalized Medicine in Cancer

Dhananjaya Saranath and Aparna Khanna

Recent technological advances have provided

decisions.

unprecedented

develop

including 'Next Generation Sequencing'

'Precision/

(NGS) with both availability and affordability

Personalized Medicine', with confluence of

will enable understanding of cancer and other

medicine and technology making significant

diseases, a feasible proposition.

platforms

opportunities

for

to

implementing

Thus,

advanced

technology

advances in treatment. The Cancer Genome

Next Generation Sequencing is massively

Atlas (TCGA), a large scale initiative started in

parallel sequencing enabling rapid sequencing

2006, to generate a comprehensive landscape

of the entire genome or exome sequencing on

for identification of alterations in tumor types

whole genome or cDNA (RNA-Seq), builds

with a view to develop better therapies, is on a

on the concept of 'NGS taking us into

wind down. The next phase is use of the

expanded genomic testing for risk prediction,

information

'Precision/

diagnosis, prognosis, treatment response and

Personalized Medicine'. Implementation of

disease free survival or overall survival in real

'Precision/Personalized Medicine' requires

time'.The understanding of the mechanisms

understanding of the biology of each cancer

and processes in cancer with single aberrations

type with precise definition of the cancer

or cumulative alterations including mutations,

genome. The different genome alterations will

rearrangements, amplifications, deletions,

identify the 'Founder Mutations' involved in

insertions and other alterations in cancer will

the early phase, but may not be associated with

be discerned. It is important to remember that

a fully transformed phenotype; 'Driver

several countries have initiated studies in this

Mutations' required for fully transformed

direction. Prime Minister David Cameroon,

phenotype;

Mutations'

UK, endorsed the 'Genomes Project' for

considered as collateral damage. Treatment

collection of data for whole genome sequences

against key oncogenic driver mutations in

from 100,000 individuals, to be completed by

individual cases with targeted drugs will be the

2017, sanctioning USD 475 million for

benefit of the 'Precision Medicine' approach.

sequencing studies, with a view to better

Rational choices for treatment have to be

understand

preceded by full genomic data and expression

cancer. Barack Obama, President, USA,

data,

launched the 'Precision Medicine' initiative

generated

and

facilitating

for

'Passenger

combination

therapy

complex

diseases

including

Biomed Res J 2015;2(1):1-5

Editorial: Precision/personalized medicine in cancer

2

with a USD 215 million for genomic data on

examples are targeted drugs Dabrafenib and

one million volunteers to accelerate patient

Trametinib, mitogen activated protein kinase

powered research that promises to accelerate

1/2

biomedical discoveries and provide clinicians

BRAFV600E/K;

with new tools, knowledge and therapies for

Bevacizumab, against vascular endothelial

individual patients. A result of better

factor A is a targeted therapy in cancers of the

understanding of cancer, is the current

colon, lung, breast, kidney and brain; whereas

repertoire of targeted therapy drugs and

Ramicirumab, a monoclonal antibody against

personalized medicine on the global scene.

vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2,

(MAPK1/2)

for

melanoma

angiogenesis

with

inhibitor,

In the past decade the advent of targeted

is used in gastric cancer and Non-small cell

therapy and new tailored drugs has led to a

lung cancer, and in combination with

revolution in treatment of lung cancer, with

Docetaxel improves outcomes in bladder

larger benefit, lower toxicity and better quality

cancer. HER2 gene antibody – Herceptin,

of life for the patient. The treatment is often

shows substantial survival benefits in all

based on molecular profiling of individual

newly diagnosed and recurrent breast cancer

patients with identified cancer, as also

patients

indicated in other cancers with a similar

expression of the gene. Development of

molecular profile. Thus, Tyrosine kinase

companion

inhibitors including Erlotinib, Gefitinib,

pathogenic molecular alterations and new

Afatinib targeting epidermal growth factor

targeted

receptors (EGFR), and ALK Inhibitors

guidelines for several molecular diagnostic

including Crizotinib, Ceritinibare beneficially

tests

used in patients with aberration of the genes in

Personalized Medicine' will enable the current

Non-small cell lung cancer, and indicated for

oncologists to 'Win the War against Cancer'.

with

diagnostics

drugs

are

amplification

go

and

indicating

hand-in-hand,

available.

Thus,

overthe

and

'Precision/

additional cancers with the appropriate

The current issue includes a review paper

molecular profile. Involvement of Kras,

and an original article on glioblastoma

EGFR, ALK, HER2, Braf, MET, AKTI,

multiforme

MAP2KI, PI3KC genes have been identified

aggressive brain tumor, a cancer with bad

in lung cancers, opening possibilities of

prognosis and median survival of 15 months.

targeted therapy with consequential benefits.

The conventional treatment of GBM using the

Thus, an additional aspect which has emerged

strategy

is combination therapy using two or more

chemotherapy,

targeted drugs, or targeted drugs plus the

incrementally in the last 30 years. With the

conventional chemotherapeutic drugs. A few

advent of molecular biology and consequent

Biomed Res J 2015;2(1):1-5

(GBM),

of

one

surgery,

has

of

the

radiation

advanced

most

and

only

Saranath and Khanna

3

improved understanding of basic tumor

for better contemporary treatment.

biology, targeted therapies have become

Nanomaterials

and

nanoparticles

cornerstones for cancer treatment. Several

including dendrimers, polymers, nanotubes,

signaling pathways including RTKs/PI3K/

oxides, and enzymes and their hybrids as

AKT/mTOR/VEGF/VEGFR are deregulated

catalysts for various sensors such as glucose

in

in

sensors, DNA sensors, neurotransmitters

and

sensors, are another facet of technological

progression of GBM. Dr. Anita Tandle and

advances with tremendous applications in

colleagues from National Cancer Institute,

health sciences. Dendrimers are synthetic

Bethesda, Maryland, USA, discuss the Omics

nanoscale compounds with unique properties,

of GBM and applications in novel therapies, in

resulting

the article, ‘Advances in Omics Technologies

applications. Dendrimers have a number of

in GBM’. The authors survey the technologies

features that make them ideally suited for

of genomics, transcriptomics, epigenomics,

sensor applications, such as, its high surface

proteomics,

post

area, high reactivity, easy dispersability and

transcriptional modifications of microRNAs

rapid fabrication. Dr. Saumya Nigam and Dr.

in GBM. A comprehensive information in

Dhirendra Bahadur, Indian Institute of

GBM will lead to better understanding of the

Technology Bombay, Mumbai, along with Dr.

cancer,

signal

Sudeshna Chandra, NMIMs (Deemed-to-be)

transduction pathways, and identify key

University, present a review on ‘Dendrimers

molecules associated with the pathogenesis,

based electrochemical biosensors’. The

culminating in development of new drugs and

review highlights the advanced development

'Personalized treatment'. The original article

of

by the group, ‘EGFR 2, EGFR and HDAC

electrochemical

triple

dendrimers. A must read review for all to

GBM,

playing

tumorigenesis,

a

treatment

major

resistance

metabolomics

highlight

inhibitor

the

role

and

various

CUDC-101

enhances

radiosensitivity of GBM cells’, convincingly

in

effective,

biomedical

rapid

and

and

biosensors

industrial

versatile

based

on

understand the technology.

shows enhancement of in vitro radiosensitivity

The concept of cancer stem cells (CSC)

of GBM and breast cancer cell lines

proposed earlier in the year 2000, are now well

selectively, with no effect on normal human

accepted to play a critical role in cancers. The

lung fibroblast cell line. The radiosensitization

CSCs are more of an enigma and relatively

of the cancer cell lines was attributed to

more difficult to decode the biology of CSCs.

inhibition of DNA double stranded break

The conserved Wnt/β-Catenin, Notch and

repair and modulation of cell cycle. A better

Sonic Hedgehog pathways regulate stem cell

understanding of the cancer will open avenues

pluripotency and cell fate decisions during

Biomed Res J 2015;2(1):1-5

Editorial: Precision/personalized medicine in cancer

4

normal embryonic development and adult

cells’ by Dr. Vaijayanti Kale and colleagues

tissue homeostasis, and aberrant activity

from the National Centre for Cell Science,

within these pathwaysis displayed in several

Pune, emphasizes importance of alternative

cancers. Human cancers contain a relatively

systems for investigating regulation of

dormant

hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs). The authors

cell

population,

CSCs,

with

characteristics similar to normal stem cells.

showed

Convincing evidence indicates that CSCs are

unequivocally

responsible

adipogenic lineage, and exhibited a higher

therapy

for

chemotherapy/radiation

resistance,

maintenance

that

the

cell

line

M210B4

differentiated

towards

and

HSC-supportive ability and conclude that the

consequent recurrence of the cancer. The roles

cell line M210B4 is an appropriate substitute

of Wnt, Notch and Hedgehog pathways in

to study HSC regulation in vitro.

cancers and their deregulation are of critical

The transcription factor Nrf2 containing

significance, directly linked to CSCs. In order

the conserved basic leucine zipper structure

to target the CSCs therapeutically, it is

belongs to the Cap 'N' Collar family, and plays

imperative to understand the molecular

a critical role in cell defense and survival

mechanisms regulating CSCs responsible for

pathways. Nrf2 often protects cells and tissues

maintenance and recurrence of cancer, and

from

develop combination therapies to target CSCs

transcription of cytoprotective genes, and

inhibiting the cumulative action of the

hence

deregulated genes. Dr. Sanjeev Waghmare and

protecting against redox-mediated injury and

his colleagues from Advanced Centre for

carcinogenesis. Paradoxically, the flip side of

Treatment, Research and Education in Cancer,

Nrf2 is protection of cancer cells from

Navi

the

chemotherapeutic agents and/or radiotherapy

intricately complex signalling cascades of

resulting in resistance to the therapy and

Wnt, Notch and Hedgehog genes, regulation

cancer

and maintenance of normal developmental

upregulated in several cancer types, and

processes, and their association in cancer, in

associated with poor prognosis in cancer

the article, ‘Developmental signalling in

patients. The dilemma of the dual action of

maintenance and regulation of cancer stem

Nrf2 has been well reviewed in the article,

cells’. Whereas, the article, ‘Phenotypic and

‘Divergent

functional

the

progression and prevention’ by Dr. Santosh

maintenance and regulation of a marrow-

Sandur and colleagues from Bhabha Atomic

derived stromal cell line, M210B4 and its

Research Centre, Mumbai. The review

comparison with primary marrow stromal

indicates a wider approach with better

Mumbai,

succinctly

characterization

Biomed Res J 2015;2(1):1-5

review

in

toxicants

and

considered

progression.

role

of

carcinogens

via

chemopreventive,

Nrf2

Nrf2

is

aberrantly

in

cancer

Saranath and Khanna

5

comprehension of the mechanisms of action of

infertility and intra-uterine growth retardation

Nrf2 and consequent design and development

are minimized or avoided in normal fetal

of drugs to handle the upregulation or

growth. The highly orchestrated embryo-

downregulation of Nrf2 in the preventive,

endometrial cross talk involves a plethora of

protective or destructive niche of normalcy

molecules including hormones, cytokines,

and diseases. Thus, 'One fit for all' is not a

growth factors, specific immune modulating

feasible solution in all conditions indicating

factors, to create the appropriate micromileu

importance

for establishing pregnancy. Dr. Deepak Modi

of

'Precision/Personalized

Medicine'.

and Mr. Pradeep Bhartiya from the National

The mechanisms of embryo implantation

Institute for Research in Reproductive Health,

and development resulting in pregnancy are

Mumbai, take us through the ‘Physiology of

comparable to cancer with respect to the

embryo-endometrial cross talk’ lucidly

growth

of

highlighting the various processes and

A receptive endometrium,

interactions. The networking interactions and

normal blastocyst, cross talk between fetal and

intricate physiology in a pregnancy is very

maternal compartments remodeling uterine

well explained. The applications in a clinical

vasculature, and selector activity comprise

scenario

innate requirements for successful pregnancy.

infertility treatment and development of

Adverse

contraceptive drugs are discussed.

processes

development.

events

and

such

mechanisms

as

preeclampsia,

for

successful

implantation,

Biomed Res J 2015;2(1):1-5

Review

Advances in OmicsTechnologies in GBM

Uday B. Maachani, Uma Shankavaram, Kevin Camphausen, Anita Tandle*

Radiation Oncology Branch, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda MD,USA

Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) is one of the most lethal human cancers and poses a great challenge in the

therapeutic interventions of GBM patients worldwide. Despite prominent recent advances in oncology, on

an average GBM patients survive 12–15 months with conventional standard of care treatment. To

understand the pathophysiology of this disease, recently the research focus has been on omics-based

approaches. Advances in high-throughput assay development and bioinformatic techniques have provided

new opportunities in the molecular analysis of cancer omics technologies including genomics,

transcriptomics, epigenomics, proteomics, and metabolomics. Further, the enormous addition and

accessibility of public databases with associated clinical demographic information including tumor

histology, patient response and outcome, have profoundly improved our knowledge of the molecular

mechanisms driving cancer. In GBM, omics have significantly aided in defining the molecular architecture of

tumorigenesis, uncovering relevant subsets of patients whose disease may require different treatments. In

this review, we focus on the unique advantages of multifaceted omics technologies and discuss the

implications on translational GBM research.

INTRODUCTION

Glioblastoma (GBM)

recurrence. As the name infers, it is

Brain tumors account for about 85–90% of all

multiforme microscopically showing regions

primary central nervous system (CNS) tumors.

of

Worldwide, approximately 343,175 new cases

multiforme genetically with various genetic

of brain and other CNS tumors were diagnosed

alterations leading to its aggressive nature.

pseudopalisading

and

hemorrhage,

in the year 2012 (http://www.cbtrus.org/).

The standard of care for treatment of GBM

Glioblastoma or Glioblastoma multiforme

includes surgical resection followed by

(GBM) is the most lethal and clinically

radiation and chemotherapy. The addition of a

challenging of brain tumors. Most patients die

chemotherapeutic agent, Temozolamide in

of their ailment in less than a year (Stupp et al.,

recent years changed the median survival of

2005). Some of the reasons for high fatality

for GBM patients to 14.6 months from 12.1

are the complex nature and diffuse character of

months with surgery and radiotherapy (Stupp

the tumor itself and the high rate of disease

et al., 2005). Also, currently there is no

Key words: Glioblastoma, Omics, Genomics, Transcriptomics, Epigenomics, Proteomics, Metabolomics.

*Corresponding Author: Anita Tandle, Radiation Oncology Branch, National Cancer Institute, 10 Center Drive

Magnuson Clinical Center Room B3-B100, Bethesda MD 20892, USA.

Email: tandlea@mail.nih.gov

Biomed Res J 2015;2(1):6-20

7

Maachani et al.

standard of care available for recurrent disease

instrumentation and bioinformatics data

and most of the patients die. Hence there is an

analysis have reshaped how we view the

urgent need to develop molecular targeted

cancer genome (Vucic et al., 2012). “Omics”

therapy for this devastating disease.

refers to the study of cancer as a whole entity

Some

responsible

of

the

for

molecular

molecules. It includes (but not limited to)

therapeutic resistance includes genetic and

DNA mutations, copy number changes,

epigenetic alterations, activation of stem cell

epigenetic changes like DNA methylation,

pathways,

tumor

transcriptome analysis and whole-genome

microenvironment and cellular metabolism.

DNA/RNA sequencing. The omics-based

However, the functional consequences of

recent

many of these alterations are largely unknown

transcriptomics, epigenomics, proteomics and

in GBM tumorigenesis (Frattini et al., 2013;

metabolomics have unveiled the molecular

Schonberg et al., 2013).

mechanisms behind various cancers and

changes

progression

focusing on the various micro- and macro-

and

and

GBM

alterations

in

the

approaches

including

genomics,

assisted in identification of next-generation

Omics

molecular markers for early diagnosis,

With the sequencing of the human genome, the

prognosis, predictive of response to treatments

study of biological systems underwent a major

and predisposition to gliomas (Cho, 2010;

genomic revolution. The major technological

Chin, 2013) (Fig. 1). The publically available

breakthroughs

multi-omics

in

high-throughput

assay

development, technological advancements in

databases

collected

by

International Cancer Genome Consortium

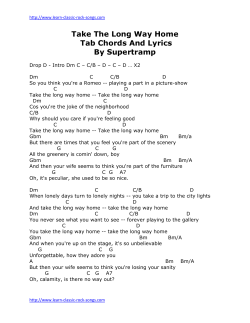

Figure 1: Omics in Glioblastoma.

Biomed Res J 2015;2(1):6-20

8

Advances in omics technologies in GBM

(ICGC) and The Cancer Genome Atlas

attempted to correlate mRNA signatures with

(http://cancergenome.nih.gov/)

network

the grades of gliomas and their clinical

group using a sample cohort of several

behavior to aid in overall prognosis and

hundred clinical specimens of GBM further

treatment response of patients (Mischel et al.,

elaborated the molecular processes funda-

2004; Kim et al., 2002). Transcriptomics is the

mental to GBM pathogenesis (Hudson et al.,

study of RNA transcripts that are produced by

2010; Verhaak et al., 2010).

the genome, under specific circumstances or

a

in a specific cell using high-throughput

Genomics/Transcriptomics

methods,

such

as

microarray

analysis,

Early work on gene expression analysis of

allowing the identification of genes that are

gliomas employed DNA microarrays and

differentially expressed in distinct cell

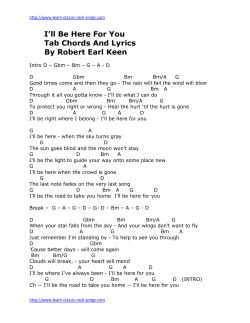

Table 1: Role of Omics in biomarkers identification and disease prognosis

GBM Biomarkers

Role in GBM prognosis

EGFR amplification

EGFR amplification is the most common event in primary GBM , with EGFRvIII being the most

EGFRvIII mutation

prominent mutated receptor tyrosine kinase receptor occurring in ~50% of GBM cases that

overexpress EGFR (Verhaak et al., 2010). A potential predictive biomarker for molecular

therapies.

PDGFRA

PDGFRA is mainly mutated and expressed in abnormally high amounts in proneural tumors

(Verhaak et al., 2010) and associated with poor prognosis in IDH1 mutant GBM (Brennan et al.,

2013).

TP53 mutation

TP53 gene although mutated, has no predictive or prognostic role. Can distinguish tumor grade

(Brennan et al., 2013).

1p/19q Co-deletion

1p/19q co-deletion is the most common genetic alteration in oligodendroglioma tumors and is

associated with favorable response to chemotherapy, radiation and survival (Alaminos et al.,

2005).

MGMT promoter

Promoter methylation of MGMT gene, inactivates DNA repair function (Esteller et al., 1999). It is

methylation

the first predictive epigenetic biomarker with a putative diagnostic role in detecting

pseudoprogression. MGMT methylation helps in molecular stratification of patients for

Temozolomide therapy (Malstrom et al., 2012).

VEGF

VEGF is considered to be the driving factor of tumor angiogenesis and has been identified in

64.1% GBMs. It is a strong predictor of survival , in patients with gliomas (Reynes et al., 2011)

PTEN

A gene level biomarker with poor survival outcomes for GBM (Baeza et al., 2003). PTEN is deleted

in 50–70% of primary and 54%–63% of secondary GBM. Also mutated in 14%–47% primary GBM.

Mutation is linked to resistance to targeted EGFR inhibitors in GBM (Deberardinis et al., 2008).

IDH1/2 mutation

IDH1 mutation is now recognized as an important driver in the etiology of low-grade and

secondary brain tumors (48). Has prognostic value in WHO grade III and IV GBM. Accumulation of

oncometabolite 2-hydroxygluatrate (2HG) considered as metabolomic imaging biomarker for

mutant IDH1 gliomas (Chen et al., 2014).

Biomed Res J 2015;2(1):6-20

9

Maachani et al.

Table 2: Molecular targeted therapies for glioblastoma

Other current strategies tested in GBMs

Pathways targeted

Agents

Molecular targets

Erlotinib (Roche)

Kinase inhibitors of

Epidermal Growth Factor Pathway

EGFR is amplified and frequently mutated in ~50% of GBMs and is

overexpressed in many malignant gliomas. Therefore could be used

Gefitinib (AstraZeneca)

EGFR

as a therapeutic targeted agent in GBM patients.

VEGF Pathway

Targeting vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) pathways to

Bevacizumab (Avastin;

Recombinant human

induce anti-angiogenic effects in the treatment of malignant gliomas

Genentech)

neutralizing monoclonal

has been in focus for past few years.

antibody to VEGF

Vatalanib (Novartis)

Kinase inhibitor of

VEGFR/PDGFR

Cediranib (AstraZeneca)

pan-VEGFR inhibitor

TGF-β is a multifunctional cytokine, which regulates gliomacell

Trabedersen (Antisense

Anti-sense TGF-β2

motility, invasion, and immune surveillance. Several small molecule

Pharma)

mRNA

Rapamycin (Sirolimus)

inhibitors of m-TOR

Transforming Growth Factor β(TGF-β) Pathway

inhibitors of TGF-β receptors have shown antitumor efficacy in

preclinical models of gliomas.

PI3K–AKT–mTOR Pathways

PI3K pathways regulate several malignant phenotypes including

antiapoptosis, cell growth, proliferation, and invasion. Activated PI3K

Temsirolimus (Sirolimus)

phosphorylates several downstream effectors, including AKT. mTOR

is a major player connecting multiple pathways downstream from

Everolimus (Novartis)

AKT.

PKC Pathways

Protein kinase C (PKC) is a serine/threonine kinase that regulates

enzastaurin (Eli-Lilly)

PKC-β inhibitor with

cell proliferation, invasion, and angiogenesis.

activity against glycogen

synthase kinase 3β

Note: Several of the above agents are being evaluated in clinical trials as monotherapies or in combination with other

treatment modalities such as chemotherapy or radiation in patients with malignant gliomas.

populations. Recent multi-omics (genomics,

(Verhaak et al., 2010). These subtypes were

transcriptomics

data

defined on the basis of distinct gene signatures

integration studies have utilized patient

and also characterized by different molecular

derived samples and cell lines to reveal

alterations and activated pathways (Verhaak et

heterogeneity among the primary GBM,

al., 2010; Brennan et al., 2013). The proneural

suggesting additional molecular subclasses:

subtype

neural, proneural, classical and mesenchymal

abnormalities in platelet-derived growth

and

proteomics)

was

mostly

characterized

by

Biomed Res J 2015;2(1):6-20

10

Advances in omics technologies in GBM

factor receptor-α (PDGFRA) or in isocitrate

methylation

dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1); whereas mutation of

promoter-associated

the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)

specific loci accompanying tumor suppression

was found in the classical subgroup, and

in GBM (Sturm et al., 2014), such as

mutations in neurofibromin 1 (NF1) were

(CDKN2A), RB1, PTEN, TP53 (Costello et

common in mesenchymal tumors. The neural

al., 1996; Nakamura et al., 2001; Baeza et al.,

subtype seemed to be similar to the classical

2003; Amatya et al., 2005) and other

subtype but with a higher frequency of TP53

previously unrecognized regulatory genes

mutations (Brennan et al., 2013). Cytogenetic

EMP3, PDGFB (Alaminos et al., 2005; Bruna

and molecular studies have also identified a

et al., 2007). Most significantly, O-6-methyl-

number

chromosomal

guanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT)

abnormalities and genetic alterations in

promoter hypermethylation was identified

malignant

novel

occurring in ~45% of adult patients with GBM

candidates, particularly in GBMs. The

(Esteller et al., 1999; Brennan et al., 2013).

identification of molecular subtypes has

MGMT hypermethylation leads to gene

revealed a set of core signaling pathways

silencing, and reduced gene expression levels

commonly activated in GBM (Table1)

which compromises its ability to repair

(Furnari et al., 2007) and could be used in

damaged DNA by alkylating agents like

molecular targeted therapies (Table 2).

Temozolomide (Felsberg et al., 2011). Thus,

of

recurrent

gliomas,

as

well

as

have

identified

frequent

hypermethylation

of

gene methylation could be used as a biomarker

to predict sensitivity to chemo- radiotherapy

Epigenomics

enzymatic

(Wick et al., 2012; Malmström et al., 2012).

modifications of DNA and associated histone

Further, based on DNA methylation patterns,

proteins to regulate gene expression. In recent

proneural subtype is classified into CpG island

years these changes have been recognized as

methylator phenotype (CIMP) positive and

important causes of phenotypic changes in

CpG–CIMP-negative GBM subsets which

human

The

strongly correlates with IDH1 gene mutation

epigenetic changes are dynamic in nature and

status (Noushmehr et al., 2010; Turcan et al.,

play an important role in gene expression and

2012). Glioma CIMP (G-CIMP) is a powerful

DNA structure.

determinant

Epigenetic

changes

cancers

involve

(Esteller,

2007).

Epigenetic alterations,

of

tumor

aggressiveness

especially those related to changes in histone

(Riemenschneider et al., 2010; Brennan et al.,

acetylation, are a recent focus for therapeutic

2013). These epigenomic and other multi-

drug targeting in clinical trials. Genomic-array

omic

(microarray)

mutations,

techniques

Biomed Res J 2015;2(1):6-20

studying

DNA

analyses

have

altered

revealed

proteins,

several

miRNA

11

Maachani et al.

expressions and pathways associated with

efficient biomarker validation, treatment

GBM pathogenesis and prognosis.

monitoring and can be translated into clinical

applications in an affordable manner. Various

Proteomics

plasma/serum

Proteomic profiling represents the large-scale

identified earlier for GBM including YKL-40,

examination of protein expression, post-

GFAP

translational modification, and understanding

(Jayaram et al., 2014). Reynes et al. (2011)

how different proteins interact with each other.

reported inflammatory markers (C-reactive

Using various bioinformatics techniques, the

protein, IL-6 and TNF-) and angiogenesis

information can be unified into protein

markers such as VEGF and soluble VEGF

networks.

histopathology

receptor 1 to be significantly elevated in the

represents the gold standard for the typing and

plasma of GBM patients. Jung et al. (2007)

grading of gliomas and depends largely on

identified GFAP as a discriminatory serum

certain architectural similarities of tumor cells

biomarker

with normal glial cells (Tohma et al., 1998;

osteopontin (OPN), validated using IHC and

Riemenschneider et al., 2010). We feel that the

ELISA in GBM patients, was shown to

underlying disease pathology would result

correlate

into differential proteomic profiling of

(Sreekanthreddy et al., 2010). In an extended

diseased tissue and the surrounding disease-

effort, the TCGA group also generated protein

free normal tissue. Recent technological

expression data from 214 GBM patient

advances in proteomics has allowed analysis

samples using a high throughput antibody-

of glioma patient biopsies, proximal fluids,

based reverse phase protein arrays (RPPAs)

cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and cyst fluid,

(Brennan et al., 2013) revealing several

plasma, glioma cell lines. This has allowed a

mutations, altered genes, proteins and their

comprehensive proteomic profiling of glioma

pathways underlying GBM pathophysiology

biology to aid the traditional histopathology in

(Dong et al., 2010).

Currently,

biomarkers

and

matrix

for

been

metalloproteinase-9

GBM.

with

have

Similarly,

poor

serum

prognosis

improving our understanding of glioma

Some of the challenges in using protein

processes and to better evaluation of drug

profiling more commonly in characterizing

responses to treatment (Somasundaram et al.,

and quantifying accepted protein biomarkers

2009). The techniques involve evaluation of

includes high costs, lengthy production times

protein arrays, including antibody and aptamer

and most importantly lack of high specificity

arrays. This allows simultaneous detection of

antibodies.

multiple

approach has the potential to identify novel

proteins/phosphoproteins.

These

high throughput techniques can be used for

diagnostic,

Moreover,

prognostic,

the

and

proteomic

therapeutic

Biomed Res J 2015;2(1):6-20

12

Advances in omics technologies in GBM

biomarkers

for

human

gliomas.

The

Spectroscopy (MRS), Nuclear Magnetic

application of proteomics in neuro-oncology

Resonance (NMR), have helped in profiling

is still in its developing stage. Please refer

global metabolomic signatures in cancers

recent reviews by Whittle et al. (2007) and

including glioma (Dunn et al., 2005; Serkova

Niclou et al. (2010) for more on the current

and Niemann, 2006). Several key differences

status of glioma proteomics and its clinical

in metabolite profiles have been identified in

applications.

GBM cancer cells when compared to normal

controls, providing a novel insight into GBM

Metabolomics

tumorigenesis (Spratlin et al., 2009). As

Nearly a century ago, Otto Warburg made a

metabolomics reflect underlying altered

seminal observation that even in the presence

genotype-phenotype, it can be used as a

of adequate oxygen cancer cells metabolize

predictive biomarker for measure of efficacy

glucose by aerobic glycolysis, termed as

and as a pharmacodynamic marker, for both

Warburg effect (Warburg et al., 1924; 1927).

traditional

Moreover,

disease-related

agents. Using the 1H-NMR spectra and neural

altered cellular metabolism has come into

networks, human glioma cell cultures can be

forefront of cancer research. Now, there is

separated into drug-resistant and drug-

increasing evidence that the underlying

sensitive groups before treatment with

genetic alterations contributing to glioma

nitrosourea treatment (El-Deredy et al., 1997).

pathogenesis is also responsible for altered

Frequent genetic alterations in glioma such as

cellular metabolism (Parsons et al., 2008).

MYC amplification, PTEN deletion or protein

Metabolomics refers to the global quantitative

loss and EFGR amplification are associated

assessment of endogenous enzyme kinetics,

with multiple downstream metabolic targets

cellular biochemical reactions, and synthesis

(Deberardinis et al., 2008). IDH1 and IDH2

of cellular metabolites within a biologic

metabolic genes are mutated in ~12% of

system, (Griffin and Shockcor, 2004; Boros et

primary gliomas, 86% of grade II and III

al., 2005). Although considerable progress has

gliomas and secondary glioblastoma through a

been made in understanding GBM biology

gain-of-function mutation that alters the

through genetic analysis, little is known about

enzymatic activity of the protein product,

the underlying metabolic alterations in glioma.

which results in the production of 2-

In recent years, several biochemical and

hydroxyglutarate (Dang et al., 2009). The

biophysical

very

Spectrometry

recently

techniques

(MS),

chromatography,

such

liquid-

Magnetic

Biomed Res J 2015;2(1):6-20

chemotherapy

and

hormonal

as

Mass

detection of 2-HG metabolic product has been

and

gel-

proposed to be a potential tool for in vivo

Resonance

distinction of secondary from primary

13

Maachani et al.

glioblastomas (Esmaeili et al., 2013). More

Srinivasan et al., 2011). More recently several

recently Chen et al. (2014) showed that

lines of evidence have implicated over-

IDH1-mutant glioma growth is facilitated by

expression of miR21 with chemo and

overexpression of glutamate dehydrogenase 2

radioresistance of GBM cells. Its expression

gene (GLUD2) and it could be targeted for

levels have been associated with glioma grade

growth

Hence,

and as a candidate independent marker for

metabolomics applications in a clinical

overall survival (Chao et al., 2013; Wu et al.,

perspective may have a favorable impact on

2013). Thus, integrative omics analysis has

glioma grade, metabolic state and treatment

revealed the importance and scope of

stratification of glioma patients.

translational

inhibitory

effects.

repression

in

microRNA-

mediated GBM pathogenesis. Please refer to

Other Omics: microRNAs

additional reviews (Sana et al., 2011; Karsy et

In recent years, microRNAs (miRNAs) have

al., 2012; Nikaki et al., 2012) for more

emerged in the forefront of cancer molecular

detailed coverage on miRNA expression and

biology.

function in GBM.

MicroRNAs

are

key

post-

transcriptional regulators that inhibit gene

expression by promoting mRNA decay or

Omics data integration methods

suppressing translation (Iorio and Croce,

The post-human genome project era has

2012). Experimental and clinical evidence

generated enormous heterogeneous and large

supports that miRNAs play pivotal role in

data sets. As vast gene profiling datasets and

cancer

proliferation,

technologies are being developed, they have

apoptosis and metastasis (Cho, 2011; Iorio and

created an unprecedented need to develop

Croce, 2012). The functional role of miRNAs

technologies to process the data in a

was first discovered in human gliomas (Li et

meaningful way. The efforts have yielded

al., 2013). Several miRNA expressions are

meaningful results in cancer biomarker

found to be dysregulated in GBM. TCGA

discovery, protein interactions and genotype

group identified alterations in 149 miRNAs

to phenotype correlations (Park et al., 2005).

(Dong et al., 2010) and an expression

However, current omics technologies cannot

signature comprising 10 miRNAs with

model

prognostic prediction (Srinivasan et al., 2011).

molecules by analyzing individual genes,

miR-128, miR-342 and miR-21 are known to

proteins or metabolites. This is often not very

play both oncogenic and tumor suppressive

effective

roles and are being explored as possible

heterogeneous nature of human cancers.

markers for GBM (Dong et al., 2010;

Cancer is a complex biological system and

gene

regulation,

interactions

due

to

between

the

multiple

complex

and

Biomed Res J 2015;2(1):6-20

14

Advances in omics technologies in GBM

requires a better understanding of the disease's

network and analyze experimental data in the

complexity at systems-level (Faratian et al.,

context of pathways using multiple source

2009; Hu et al., 2013). Pathway and network

omics data (Wang et al., 2012; Blazier and

based methods have taken more important role

Papin, 2012; Federici et al., 2013). Although

in analysis of high-throughput data, that can

currently there are tools available to process

provide a global and systematical way to

large datasets generated by one platform, it is

explore the relationships between biomarkers

expected that soon tools combining data

and their interacting partners (Wang et al.,

across multiple platforms will be available to

2015). Integration of data from multiple omic

researchers. This will help in integrating

studies can not only help unravel the

research results into a framework of whole

underlying

biological systems to support translation of

molecular

mechanism

of

carcinogenesis but also identify the signature

research into clinical applications.

of signaling pathway/networks characteristic

for specific cancer types that can be used for

Omics Advantages in GBM therapy

diagnosis, prognosis and designing tumor

So far clinical translation of an effective GBM

targeted therapy.

therapy has been hindered by multiple factors,

Most recently, attempts at integration of

including diffuse infiltration at the time of

multiple high-throughput omics data have

diagnosis, significant cellular heterogeneity

concentrated on comparing data acquired

(both

using

conditions/

difficulty in crossing the blood-brain barrier

platforms to explore functional and regulatory

by effective drugs, and the role of tumor

associations between genes and proteins

progenitor cells in reestablishment of resistant

(Faith et al., 2007; McDermott et al., 2009).

disease following chemo and radiotherapy.

This has culminated into combining functional

Current standard treatment of GBM consists

characterization and quantitative interactions

of attempted gross total surgical resection

extracted from various biomolecules such as

followed by concurrent temozolomide and

DNA, mRNA, proteins and metabolites (Chen

radiation therapy (RT) (Clarke et al., 2010).

et al., 2011; Coban and Barton, 2012; Mitchell

Although, RT provides good local control, it is

et al., 2013) (Fig. 1). Some analysis utilizes

not very beneficial in controlling the disease

pathways in the form of connected routes

recurrence. In case of GBM, majority of

through a graph-based representation of the

patients die from recurrent disease, as

metabolic network (Blum and Kohlbacher,

currently there is no effective therapy for

2008). Other approaches focus on the

recurrent GBM. Therefore, the addition of

functional module of protein interaction

systemic chemotherapy to RT can help in

various

experimental

Biomed Res J 2015;2(1):6-20

intratumoral

and

intertumoral),

15

Maachani et al.

controlling

recurrence

and

offering

an

methyl group to the middle guanine in a GGG

additional radiosensitization benefits in GBM,

sequence to convert it to O6-methylguanine.

benefiting both definitive and palliative

Temozolomideexerts

strategies for disease management (Stupp R et

activity by interfering with repair of damaged

al., 2006; Clarke et al., 2010). So far non-

DNA after radiation treatment (Mrugala and

omics studies have identified few GBM targets

Chamberlain, 2008). In a recent randomized

at the protein level, but fail to see an overall

trial,

role of molecules in signaling pathways,

Temozolomide chemotherapy with radiation,

protein-protein interactions, and role in

significantly

metabolic processes. Unfortunately so far only

survival from 12.1 months to 14.6 months, for

one drug has been identified (Temozolomide)

GBM patients (Stupp et al., 2005, Clarke et al.,

which can radiosensitize GBM patients. Thus,

2010). The consequent analysis of these

non-omics techniques will compliment whole

patients by Hegi et al. (2005) reported that

genomic/epigenomics/metabolomics approach

patients with methylated MGMT gene

of omics technologies. Without publically

promoter were benefited from this treatment

available databases, the surge of preclinical

compared to patients with unmethylated

and clinical information seen in the GBM field

MGMT promoter. The MGMT promoter

over last few years, would have not been

methylation silences the gene function

possible. As omics studies expand our

required

understanding of the molecular pathways

methylation and therefore cannot counteract

driving GBM tumorigenesis, more druggable

the action of Temozolomide. Thus, omics has

targets will be identified to treat GBM patients.

been helpful in predicting tumor response to

Also, understanding of ionizing radiation at

Temozolomide and to guide clinical decision

the level of molecular biology will lead to

making. The other most common types of

development and production of targeted

chemotherapies for GBM under investigation

radiosensitizers. Temozolomide is currently

include

the only radiosensitizing agent used for GBM

antiangiogenic therapies, immunotherapies,

with class I evidence of benefit (Mrugala and

gene

Chamberlain, 2008). It is a novel oral

therapies and drugs to overcome resistance

bioavailable

(Table 2).

second-generation

alkylating

its

concomitant

to

and

improved

reverse

targeted

therapies,

antineoplastic

adjuvant

progression

the

molecular

free

O6-guanine

therapies,

radiation-enhancement

agent. At physiologic pH it undergoes

hydrolysis to its active form methyltraizeno-

Challenges and Prospective

imidazoleoarboxamid

The

Oncogenic transformation is a complex,

mechanism of action of MTIC, is to transfer a

multistep process that differs widely between

(MTIC).

Biomed Res J 2015;2(1):6-20

16

Advances in omics technologies in GBM

and even within cancer types. Advances in the

therapeutic agents for GBM. The advances

large scale omics technologies have led to

with respect togene expression profiling,

identification of promising GBM disease

signaling pathway characterization, glioma

biomarkers. The major challenge is how to

stem cell identification, regulatory RNA

bring omics research into accurate and reliable

studies,

clinical use. In case of GBM, omics

immunomodulation approaches, have resulted

technologies have their limitations due to late

in several ongoing clinical studies evaluating

diagnosis of disease, intrinsic molecular

new therapeutic agents for GBM (Table 2). It is

complexity and genetic heterogeneity of

evident that omics based cancer research is

GBMs. To find consistencies that can be

going to play a pivotal role in diagnosis,

therapeutically targeted on the basis of

treatment and monitoring of GBM patients.

metabolomic

changes

and

molecular analysis, poses a major problem.

However, we are optimistic that the wealth of

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

information generated by omics techniques

The authors claim no conflict of interest.

has paved a roadmap for designing new

REFERENCES

Alaminos M, Davalos V, Ropero S, SetienF, Paz

relevant metabolic routes for interactive

MF, Herranz M, et al. EMP3, a myelin-related

network

gene located in the critical 19q13.3 region, is

Bioinformatics 2008;24:2108–2109.

navigation

and

visualization.

epigenetically silenced and exhibits features

Boros LG, Lerner MR, Morgan DL, Taylor SL,

of a candidate tumor suppressor in glioma and

Smith BJ, Postier RG, Brackett DJ, et al. [1,2-

Cancer

13C2]-D-glucose profiles of the serum, liver,

neuroblastoma.

Res

2005;65:

2565–2571.

Amatya V, Naumann U, Weller M, Ohgaki H. TP53

promoter methylation in human gliomas. Acta

Neuropathol 2005;110:178–184.

Baeza N, Weller M, Yonekawa Y, Kleihues P,

Ohgaki H. PTEN methylation and expression

in glioblastomas. Acta Neuropathol 2003;

106:479–485.

pancreas, and DMBA-induced pancreatic

tumors of rats. Pancreas 2013;31:337–343.

Brennan CW, Verhaak RG, McKenna A, Campos

B, Noushmehr H, Salama SR, et al. The

somatic genomic landscape of glioblastoma.

Cell 2013;155:462–477.

Bruna A, Darken RS, RojoF, Ocana A, Penuelas S,

Arias A, et al. High TGFbeta-Smad activity

Blazier, AS, Papin JA. Integration of expression

confers poor prognosis in glioma patients and

data in genome-scale metabolic network

promotes cell proliferation depending on the

reconstructions. Frontiers in Physiology 2012;

methylation of the PDGF-B gene. Cancer Cell

3:299.

2007;11:147–160.

Blum T, Kohlbache, O. MetaRoute: fast search for

Biomed Res J 2015;2(1):6-20

Cha TF, Xiong HH, Liu W, Chen Y, Zhang JX.

17

Maachani et al.

MiR-21 mediates the radiation resistance of

MA, Driggers EM, et al. Cancer-associated

glioblastoma cells by regulating PDCD4 and

IDH1 mutations produce 2-hydroxyglutarate.

hMSH2. Journal of Huazhong University of

Nature 2009;462:739–744.

Science and Technology. Medical sciences

2013;33:525–7529.

Thompson CB. The biology of cancer:

Chen MH, Yang WL, Lin KT, Liu CH, Liu YW,

Huang KW, et al. Gene expression-based

chemical

Deberardinis RJ, Lum JJ, Hatzivassiliou G,

genomics

identifies

metabolic reprogramming fuels cell growth

and proliferation. Cell Metab 2008. 7:11–20.

potential

Dong H, Luo L, Hong SJ, Siu HC, Xiao YH, Jin L,

therapeutic drugs in hepatocellular carcinoma.

et al. Integrated analysis of mutations, miRNA

PloS one 2011; 6:e27186.

and mRNA expression in glioblastoma. BMC

Chen RH, Nishimura MC, Kharbanda S, Peale F,

Deng YZ, Daemen A, et al. Hominoid-specific

enzyme

GLUD2

promotes

growth

of

IDH1(R132H) glioma. Proc Natl Acad Sci

USA 2014;111:14217–14222.

Syst Biol 2010; 4:163.

Dunn WB, Bailey NJ, Johnson HE. Measuring the

metabolome: current analytical technologies.

Analyst 2005;130:606–625.

ElDeredy W, Ashmore SM, Branston NM, Darling

Chin L. Comprehensive genomic characterization

JL, Williams SR, Thomas DGT. Pretreatment

defines human glioblastoma genes and core

prediction of the chemotherapeutic response

pathways (vol 455, pg 1061, 2008). Nature

of human glioma cell cultures using nuclear

2013;494:506–506.

magnetic

Cho WC. Circulating microRNAs as minimally

invasive biomarkers for cancer theragnosis

and prognosis. Front Genet 2011;2:7.

resonance

spectroscopy

and

artificial neural networks. Cancer Res 1997;

57:4196–4199.

Esmaeili M, Vettukattil R, Bathen TF. 2-

Cho WCS. An omics perspective on cancer

Hydroxyglutarate as a Magnetic Resonance

research, (Springer, Dordrecht; New York,

Biomarker for Glioma Subtyping. Transl

2010).

Oncol 2013;6:92–98.

Clarke J, Butowski N, Chang S. Recent advances in

Esteller M, Hamilton S, Burger P, Baylin S,

therapy for glioblastoma. Arch Neurol 2010;

Herman J. Inactivation of the DNA repair gene

67:279–283.

O6-methylguanine-DNA

methyltransferase

Coban Z, Barton MC. Integrative genomics: liver

by promoter hypermethylation is a common

regeneration and hepatocellular carcinoma. J

event in primary human neoplasia. Cancer Res

Cell Biochem 2012;113: 2179–2184.

1999;59:793–797.

Costello J, Berger M, Huang H, Cavenee W.

Esteller

M.

Cancer

epigenomics:

DNA

Silencing of p16/CDKN2 expression in human

methylomes and histone-modification maps.

gliomas by methylation and chromatin

Nat Rev Genet 2007; 8:286–298.

condensation.

Cancer

Res

1996;56:

2405–2410.

Dang L, White DW, Gross S, Bennett BD, Bittinger

Faith JJ, Hayete B, Thaden JT, Mogno I,

Wierzbowski J, Cottarel G, et al. Large-scale

mapping and validation of Escherichia coli

Biomed Res J 2015;2(1):6-20

18

Advances in omics technologies in GBM

transcriptional regulation from a compendium

of expression profiles. PLoS Biol 2007;5: e8.

Hu YF, Li JQ, Yan WY, Chen JJ, Li Y, Hu G, Shen

BR. Identifying novel glioma associated

Faratian D, Goltsov A, Lebedeva G, Sorokin A,

pathways based on systems biology level

Moodie S, Mullen P, et al. Systems biology

meta-analysis. BMC Syst Biol 2013;7:Suppl

reveals new strategies for personalizing cancer

2,S9.

medicine and confirms the role of PTEN in

Hudson TJ, Anderson W, Aretz A, Barker AD, Bell

resistance to trastuzumab. Cancer Res 2009;

C, Bernabe RR., et al. International network of

69:6713–6720.

cancer genome projects. Nature 2010;464:

Federici G, Gao X, Slawek J, Arodz T, Shitaye A,

Wulfkuhle JD, et al. Systems analysis of the

993–998.

Iorio MV, Croce CM. MicroRNA dysregulation in

NCI-60 cancer cell lines by alignment of

cancer:

protein pathway activation modules with "-

therapeutics. A comprehensive review. EMBO

OMIC" data fields and therapeutic response

Mol Med 2012;4:143–159.

signatures. Mol Cancer Res 2013;11:676–685.

Felsberg J, Thon N, Eigenbrod S, Hentschel B,

diagnostics,

monitoring

and

Jayaram S, Gupta MK, Polisetty RV, Cho WC,

Sirdeshmukh

R.

Towards

developing

Sabel MC, Westphal M, et al. Promoter

biomarkers for glioblastomamultiforme: a

methylation and expression of MGMT and the

proteomics view. Expert Rev Proteomics

DNA mismatch repair genes MLH1, MSH2,

2014;11:621–639.

MSH6 and PMS2 in paired primary and

Jung CS, Foerch C, Schanzer A, Heck A, Plate KH,

recurrent glioblastomas. Int J Cancer 2011;

Seifert V, et al. Serum GFAP is a diagnostic

129:659–670.

marker for glioblastoma multiforme. Brain

Frattini V, Trifonov V, Chan JM, Castano A, Lia M,

2007; 130:3336–3341.

Abate F, et al. The integrated landscape of

Karsy M, Arslan E, Moy F. Current progress on

driver genomic alterations in glioblastoma.

understanding microRNAs in glioblastoma

Nature Genet 2013;45:1141–1149.

multiforme. Genes & Cancer 2012; 3:3–15.

Furnari FB, Fenton T, Bachoo RM, Mukasa A,

Kim S, Dougherty ER, Shmulevich I, Hess KR,

Stommel JM, Stegh A, et al. Malignant

Hamilton SR, Trent JM, et al. Identification of

astrocyticglioma: genetics, biology, and paths

combination

to

treatment.

Genes

&

Dev

2007;21:

2683–2710.

Griffin JL, Shockcor JP. Metabolic profiles of

cancer cells. Nat Rev Cancer 2004;4:551–561.

Hegi ME, Diserens A, Gorlia T, Hamou M, de

gene

sets

for

glioma

classification. Mol Cancer Ther 2002;1:

1229–1236.

Li M, Li J, Liu L, Li W, Yang Y, Yuan J. MicroRNA

in

Human

Glioma.

Cancers

2013;5:

1306–1331.

Tribolet N, Weller M, et al. MGMT gene

Malmstrom A, Gronberg BH, Marosi C, Stupp R,

silencing and benefit from temozolomide in

Frappaz D, Schultz H, et al. Temozolomide

glioblastoma. N Engl J Med 2005;352:

versus standard 6-week radiotherapy versus

997–1003.

hypofractionated radiotherapy in patients

Biomed Res J 2015;2(1):6-20

19

Maachani et al.

older than 60 years with glioblastoma: the

Nordic randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet

Oncol 2012;13:916–926.

Cell 2010;17:510–522.

Park SJ, Lee SY, Cho J, Kim TY, Lee JW, Park JH,

Han MJ. Global physiological understanding

McDermott JE, Taylor RC, Yoon H, Heffron F.

and metabolic engineering of microorganisms

Bottlenecks and hubs in inferred networks are

based on omics studies. Appl Microbiol

important

Biotechnol 2005;68:567–579.

for

virulence

in

Salmonella

typhimurium. J Comput Biol 2009;16:

Parsons DW, Jones S, Zhang XS, Lin JCH, Leary

RJ, Angenendt P, et al. An integrated genomic

169–180.

Mischel PS, Cloughesy TF, Nelson SF. DNAmicroarray analysis of brain cancer: molecular

classification for therapy. Nat Rev 2004;5:

782–792.

analysis of human glioblastomamultiforme.

Science 2008;321:1807–1812.

Reynes G, Vila V, Martin M, Parada A, Fleitas T,

Reganon E, Martinez-Sales V. Circulating

Mitchell HD, Eisfeld AJ, Sims AC, McDermott JE,

markers of angiogenesis, inflammation, and

Matzke MM, Webb-Robertson BJM, et al. A

coagulation in patients with glioblastoma. J

network integration approach to predict

Neurooncol 2011;102:35–41.

conserved regulators related to pathogenicity

Riemenschneider MJ, Jeuken JW, Wesseling P,

of influenza and SARS-CoV respiratory

Reifenberger G. Molecular diagnostics of

viruses. PloS One 2013;8:e69374.

gliomas: state of the art. Acta Neuropathol

Mrugala MM, Chamberlain MC. Mechanisms of

2010;120(5):567-584.

disease: temozolomide and Glioblastoma –

Sana J, Hajduch M, Michalek J, Vyzula R, Slaby O.

look to the future. Nat Clin Pract Oncol 2008;

MicroRNAs and glioblastoma: roles in core

5:476–486.

signalling pathways and potential clinical

Nakamura M, Yonekawa Y, Kleihues P, Ohgaki H.

Promoter hypermethylation of the RB1 gene in

glioblastomas. Lab Invest 2001; 81:77–82.

Niclou SP, Fack F, Rajcevic U. Glioma proteomics:

status and perspectives. J Proteomics 2010;73:

1823–1838.

in

gliomagenesis:

targeting

miRNAs in glioblastomamultiforme therapy.

Expert

Opin

1636–1644.

Schonberg DL, Bao S, Rich JN. Genomics informs

glioblastoma biology. Nat Genet 2013;45:

1105–1107.

Serkova NJ, Niemann CU. Pattern recognition and

Nikaki A, Piperi C, Papavassiliou AG. Role of

microRNAs

implications. J Cell Mol Med 2011;15:

Investig

Drugs

2012;21:

1475–1488.

Noushmehr H, Weisenberger DJ, Diefes K, Phillips

HS, Pujara K, Berman BP, et al. Identification

biomarker validation using quantitative 1HNMR-based metabolomics. Expert Rev Mol

Diagn 2006;6:717–731.

Somasundaram K, Nijaguna MB, Kumar DM.

Serum proteomics of glioma: methods and

applications. Expert Rev Mol Diagn 2009;9:

695-707.

of a CpG island methylator phenotype that

Spratlin JL, Serkova NJ, Eckhardt SG. Clinical

defines a distinct subgroup of glioma. Cancer

applications of metabolomics in oncology: a

Biomed Res J 2015;2(1):6-20

20

Advances in omics technologies in GBM

review. Clin Cancer Res 2009;15:431–440.

Qi Y, Wilkerson MD, et al. Integrated genomic

Sreekanthreddy P, Srinivasan H, Kumar DM,

analysis identifies clinically relevant subtypes

Nijaguna MB, Sridevi S, Vrinda M, et al.

of

Identification of potential serum biomarkers of

abnormalities in PDGFRA, IDH1, EGFR, and

glioblastoma:

NF1. Cancer Cell 2010;17:98–110.

serum

osteopontin

levels

correlate with poor prognosis. Cancer Epidem

Biomar 2010;19:1409–1422.

glioblastoma

characterized

by

Vucic EA, Thu KL, Robison K, Rybaczyk LA,

Chari R, Alvarez CE, Lam WL. Translating

Srinivasan S, Patric IR, Somasundaram K. A tenmicroRNA expression signature predicts

survival in glioblastoma. PloS One 2011;6:

cancer 'omics' to improved outcomes. Genome

Res 2012;22:188–195.

Wang J, Zuo Y, Man YG, Avital I, Stojadinovic A,

Liu M, et al. Pathway and network approaches

e17438.

Stupp R, Hegi ME, van den Bent MJ, Mason WP,

for identification of cancer signature markers

Weller M, Mirimanoff RO, et al. Changing

from omics data. J Cancer 2015;6:54–65.

paradigms – an update on the multidisciplinary

Wang JL, Zhang YJ, Marian C, Ressom HW.

management of malignant glioma. Oncologist

Identification of aberrant pathways and

2006;11:165–180.

network activities from high-throughput data.

Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, Weller M,

Brief Bioinform 2012;13:406–419.

Fisher B, Taphoorn MJB, et al. Radiotherapy

Warburg O, Posener K, Negelein E. Uber den

plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide

Stoffwechsel der Carcinomzelle. Biochem

for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med 2005;352:

Zeitschr 1924;152:309–344.

987–996.

Warburg O, Wind F, Negelein E. The metabolism

Sturm D, Bender S, Jones DTW, Lichter P, Grill J,

Becher O, et al. Paediatric and adult

glioblastoma:

multiform

of tumors in the body. J Gen Physiol 1927;8:

519–530.

(epi)genomic

Whittle IR, Short DM, Deighton RF, Kerr LE,

culprits emerge. Nat Rev Cancer 2014;14:

Smith C, McCulloch J. Proteomic analysis of

92–107.

gliomas. Br J Neurosurg 2007;21, 576–582.

Tohma Y, Gratas C, Van Meir EG, Desbaillets I,

Wick W, Platten M, Meisner C, Felsberg J,

Tenan M, Tachibana O, et al. Necrogenesis and

Tabatabai G, Simon M, et al. Temozolomide

Fas/APO-1 (CD95) expression in primary (de

chemotherapy alone versus radiotherapy alone

J

for malignant astrocytoma in the elderly: the

novo)

and

secondary

glioblastomas.

Neuropathol Exp Neurol 1998;57:239–245.

Turcan S, Rohle D, Goenka A, Walsh LA, Fang F,

Yilmaz E, et al. IDH1 mutation is sufficient to

establish

the

gliomahypermethylator

phenotype. Nature. 2012;483:479–483.

Verhaak RGW, Hoadley KA, Purdom E, Wang V,

Biomed Res J 2015;2(1):6-20

NOA-08 randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet

Oncol 2012;13:707–715.

Wu L, Li G, Feng DY, Qin HZ, Gong L, Zhang J,

Zhang ZG. MicroRNA-21 expression is

associated with overall survival in patients

with glioma. Diagn Pathol 2013; 8.

Review

Dendrimers based Electrochemical Biosensors

Saumya Nigam1, Sudeshna Chandra2, Dhirendra Bahadur1*

1

Department of Metallurgical Engineering and Material Science, Indian Institute of Technology Bombay, Powai,

Mumbai, India

2

Department of Chemical Sciences, School of Science, NMIMS (Deemed-to-be) University, Vile Parle (W), Mumbai,

India

Electrochemical biosensors are portable devices that permit rapid detection and monitoring of biological,

chemical and toxic substances. In the electrochemical biosensors, the bioreceptor is incorporated into the

transducer surface; and when in contact with the analyte, generates measurable signals proportional to the

analyte concentration. Materials with high surface area, high reactivity, and easy dispersability, are most

suited for use in biosensors. Dendrimers are nanomaterial gaining importance for fabrication of

electrochemical biosensors. These are synthetic macromolecules with regularly branched tree-like and

globular structure. The potential applications of dendrimers as biosensors are explored due to their

geometric symmetrical structure, chemical stability, controlled shape and size, and varied surface

functionalities, with adequate functional groups for chemical fixation. The current review provides multifaceted use of dendrimers for developing effective, rapid, and versatile electrochemical sensors for

biomolecules. The redox centers in the dendrimers play an important role in the electron transfer process

during immobilization of biomolecules on the electrodes. This has led to an intensive use of dendrimer

based materials for fabrication of electrochemical sensors with improved analytical parameters. The review

emphasizes development of new methods and applications of electrochemical biosensors based on novel

nanomaterials.

INTRODUCTION

Dendrimers

are

globular

repetitive and radial branching units and the

macromolecules with well-defined, mono-

terminal functional groups. To achieve a high

disperse,

spatial

degree of precision and structural order,

conformations, and a wide spectrum of

dendrimers are synthesized in a stepwise

chemical and physical properties (Tomalia et

fashion. The number of repeat branching

al., 1985). These characteristics indicate

molecules used during the synthesis refers to

significant differences from the classical

the generation of dendrimers, which also

polymeric molecules. Structurally, these

governs the shape and size of the dendrimers.

macromolecules are divided into three

Generally, two different methods namely,

architectural

divergent and convergent, are adopted for the

three

hyperbranched

dimensional

regions:

the

central

core,

Key words: Dendrimers, Biosensors, Polyamidoamine, Polypropylene imine, Bioreceptors, DNA sensor.

*Corresponding Author: Dhirendra Bahadur, Department of Metallurgical Engineering and Material Science,

Indian Institute of Technology Bombay, Powai, Mumbai, India.

Email: dhirenb@iitb.ac.in

Biomed Res J 2015;2(1):21-36

Dendrimers based electrochemical biosensors

22

synthesis of dendrimers, and classified into

geometric progression with every generation

different “generations”. It is the hyper-

followed by increase in molecular weight.

branching of the molecule from the centre of

This compromises the reaction kinetics,

the dendrimer towards the periphery that

making it slower and synthesis of high

results in homostructural layers between the

generation dendrimers becomes difficult,

focal points (branching points). The number of

further lowering the yield of desired product.

focal points from the core towards the outer

Addition of each branching unit requires care

surface is the generation number. Thus,

and precision to prevent structural defects and

generation refers to the number of repeated

asymmetry in the dendrimer structure.

branching cycles performed during the

Secondly, the separation of desired dendrimer

synthesis. The core part of the dendrimer is

from the by-products is hindered due to

denoted generation “zero” (G0). For example

molecular similarity exhibited by the by-

if a dendrimer is made by convergent

product as well as the desired dendrimer. On

synthesis, and the branching reactions are

the other hand, convergent method employs

performed onto the core molecule three times,

synthesis of small dendrites from the exterior

the resulting dendrimer is considered a third

and the reaction proceeds inwards to the

generation

central core. The convergent procedure results

dendrimer.

Each

successive

generation results in a dendrimer roughly

in

lesser

twice the molecular weight of the previous

purification of dendrimers resulting in high

generation.

degree

of

structural

defects

monodispersity.

and

easy

Despite

the

The two synthetic methods have inherent

possibility of purer and flawless dendrimers,

advantages and disadvantages. Using the

the convergent method falls short in synthesis

divergent synthesis method, the dendritic

of higher generation dendrimers. This choice

molecule is formed from a central core which

is limited due to the steric forces crowding the

then extends radially outwards through

dendrites around the central core molecule.

addition of branching molecules. The main

Despite the difficulties, these macro-

advantage of the divergent method is that high

molecules have gained interest over classical

molecular

is

polymers due to the varied options presented

attained with desired repetitive branching

by dendritic macromolecules. The freedom of

monomers. Thus, the dendrimer can be tailor

choice of central core, branching monomeric

made to achieve maximum functionalities and

units and surface functional groups from the

properties. However, two major challenges are

vast pool of molecules gives rise to a

encountered in divergent synthesis. First, the

multivalent system. Ethylenediamine, 1,4-

number of reaction points increase in

diaminobutane,

nanoscaffold

Biomed Res J 2015;2(1):21-36

architecture

1,12-diaminododecane,

23

Nigam et al.

cystamine, 1,6-diaminohexane and ammonia

sensor response to be used in biosensing

are the most common core molecules. The

applications.

Various

varied core and branching monomers affect

ferrocene,

polystyrene,

the internal chemical environment, three

carbohydrates, etc. have been explored for

dimensional structures and size of internal

surface modification (Ashton et al., 1997;

cavities in the dendrimer. Due to the different

Chen et al., 2014; Hung et al., 2013; Yoon et

structural and chemical properties, these user-

al., 2000). The conductivity of the moieties

customized dendrimers find applications in