The Political Culture of the Sister Republics, 1794-1806

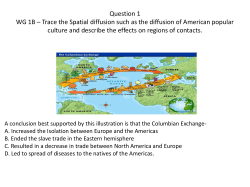

Table of Contents Timeline of the Sister Republics (1794-1806) 9 The political culture of the Sister Republics 17 ‘The political passions of other nations’ 33 Joris Oddens and Mart Rutjes National choices and the European order in the writings of Germaine de Staël Biancamaria Fontana 1. The transformation of republicanism The transformation of republicanism in the Sister Republics 43 ‘Republic’ and ‘democracy’ in Dutch late eighteenth-century revolutionary discourse 49 New wine in old wineskins 57 Andrew Jainchill Wyger R. E. Velema Republicanism in the Helvetic Republic Urte Weeber 2. Political concepts and languages Revolutionary concepts and languages in the Sister Republics of the late 1790s 67 Useful citizens. Citizenship and democracy in the Batavian Republic, 1795-1801 73 Pasi Ihalainen Mart Rutjes From rights to citizenship to the Helvetian indigénat 85 Political integration of citizens under the Helvetic Republic Silvia Arlettaz The battle over ‘democracy’in Italian political thought during the revolutionary triennio, 1796-1799 Mauro Lenci 97 3. The invention of democratic parliamentary practices Parliamentary practices in the Sister Republicsin the light of the French experience 109 Making the most of national time 115 The invention of democratic parliamentary practicesin the Helvetic Republic 127 The Neapolitan republican experiment of 1799 135 Malcolm Crook Accountability, transparency, and term limits in the first Dutch Parliament (1796-1797) Joris Oddens Some remarks André Holenstein Legislation, balance of power, and the workings of democracy between theory and practice Valeria Ferrari 4. Press, politics, and public opinion Censorship and press liberty in the Sister Republics 143 1798: A turning point? 151 Some reflections Simon Burrows Censorship in the Batavian Republic Erik Jacobs Censorship and public opinion 159 Liberty of press and censorship in the first Cisalpine Republic 171 Press and politics in the Helvetic Republic (1798-1803) Andreas Würgler Katia Visconti 5. The Sister Republics and France Small nation, big sisters 183 The national dimension in the Batavian Revolution 187 The constitutional debate in the Helvetic Republic in 1800-1801 201 An unwelcome Sister Republic 211 Pierre Serna Political discussions, institutions, and constitutions Annie Jourdan Between French influence and national self-government Antoine Broussy Re-reading political relations between the Cisalpine Republic and the French Directory Antonino De Francesco Bibliography 219 List of contributors 245 Notes 249 Index 319 The political culture of the Sister Republics Joris Oddens and Mart Rutjes On the morning of Monday, 22 January 1798, the inhabitants of The Hague witnessed a revolution within a revolution. Almost exactly three years earlier, reformist Dutch citizens had proclaimed the so-called ‘Batavian’ Revolution after the invasion of a French revolutionary army had caused the oligarchic regime of the Orangist stadholder to implode. In May 1795, the French had off icially recognized the independence of a Batavian Republic. In March 1796, the Batavian revolutionaries had established a Nationale Vergadering, a legislative and constituent assembly loosely modelled on the French Assemblée Nationale. In May 1797, the members of this Dutch National Assembly had completed a draft constitution, which was then put to a popular vote some months later. The outcome of the first referendum in Dutch history was dramatic: eighty per cent of the voters had rejected the draft constitution, which most had considered a weak compromise between different views that had struggled for dominance in the first Dutch parliament. A second National Assembly was elected, but this constituent body was faced with a similar deadlock of opinions. In the fifth month after the second Nationale Vergadering had first gathered in The Hague, on the said 22 January 1798, a radical minority staged a coup d’état and purged the parliament of its most insistent political adversaries. This act would turn the Batavian Revolution on its head.1 Between the French invasion of January 1795 and the coup of January 1798, the French Directoire had refrained from direct intervention in Dutch politics, as it had taken the position that the Batavians would be of most use as military allies when they were allowed to have a stable and independent republic. Now, after three years of difficult and fruitless deliberations over the constitution that was to guide this republic, it had instructed Charles Delacroix, the new French envoy to the Batavian Republic, to intervene more actively than his predecessor had done and make clear to the Batavian politicians that the French government would not tolerate any further delays.2 Delacroix gave his support to the coup that the Dutch radicals had been preparing, putting an end to the policy of French non-interventionism in internal political matters.3 18 Joris Oddens and Mart Rutjes On the same day, another sequence of major events occurred some 550 kilometres southwest of The Hague. In the city of Basel, delegates from all over the Swiss canton gathered in the Münster church to hear how the city council had decreed that the citizens of the city of Basel and those of the surrounding countryside would henceforth enjoy perfectly equal rights. The council had succumbed to the demands of representatives of the rural population, who had solemnly declared that they would not settle for less than ‘freedom, liberty and the sacred inalienable rights of the people’, as well as a constitution and a ‘national’ assembly that was to consist of citizens from both city and countryside. On the central square in front of the church, a tree of liberty was erected to celebrate the ‘unification’ of the people of Basel, inaugurating the ‘Helvetic’ Revolution. The Basel city government had come to embrace the need for change voluntarily, but not necessarily with great enthusiasm. More than by the revolutionary spirit that swept through the canton, its decision seems to have been prompted by the persistent rumour that a large French army was ready to intervene if the revolutionary demands of the people were not met. As had been the case in many cities of the Dutch Republic three years earlier, the mere threat of a French intervention had triggered a process of reform from within. 4 The Helvetic revolutionaries would not be granted as much room for manoeuvre as the Batavians three years earlier. In the weeks and months following the revolutionary events in Basel, citizens in many Swiss towns and villages forced their government to agree to reforms or step down. No such concessions were made, however, by the aristocratic government of the city state of Bern, which condemned the spirit of revolution and made plans to reconquer the Pays de Vaud, the Francophone canton that had been subject to German-speaking Bern until it had declared itself independent some weeks previously. On 28 January 1798, the French reacted by marching into the Swiss territory on the pretext of protecting the rights of the people of the Vaud against the Bernese; when negotiations failed, the French army moved against Bern, which fell on 5 March, breaking the resistance of the Swiss ancien régime. 5 It was the French general Brune who proclaimed, on 22 March, the unitary Helvetic Republic. Unlike the Batavians, who had been able to make the framing of a constitution a collective effort, the Helvetic people were forced to settle for a constitution written by Peter Ochs, a revolutionary from Basel who had intended the text of this constitution as a draft, and edited by the French Directors Jean-François Reubell and Philippe-Antoine Merlin de Douai.6 The imposing of a constitution that unified the Swiss confederacy dealt a severe blow to the enthusiasm The political culture of the Sister Republics 19 of many of the Swiss revolutionaries, even among those who had initially been in favour of a French intervention. Still further to the southeast, on the other side of the Alps, the citizens of Verona were witness to an entirely different event. On 22 January 1798, the French army abandoned the city to the Austrians, who entered through the city gates that very day.7 The French retreat followed from the Treaty of Campo Formio, which had stipulated the partial cession of the Venetian territories to the Emperor. For Napoleon’s armée d’Italie, the abandonment of Verona ended an episode that had caused serious damage to its desired image of a revolutionary army of liberation. In what has come to be known as the Pasque Veronesi, the people of Verona had revolted against what they considered a French occupation on Easter Monday 1797, taking over the city and its castles. A week later, the French had regained control when 15,000 soldiers had come to the rescue of the overpowered garrison, but it had by then become painfully clear that the French were unwanted in the city. When in the summer of 1797 the French had organized the first-ever free elections for the Veronese city government, the citizens had responded by electing the heroes of the counter-revolutionary revolt, after which the elections had been cancelled and the French military authorities had appointed a ‘democratic’ government of their choice.8 Now, six months later, the undesired ‘revolution’ of Verona was over. Some 140 kilometres west of Verona, in the Milanese Palazzo di Governo (the current seat of the Italian state archives), the Gran Consiglio of the ‘Cisalpine’ Republic seemed to experience a relatively ordinary day. The members of the lower house of the Cisalpine bicameral legislature discussed the grain and rice trade, the nomination of candidates for vacant positions in the departmental governments, and a proposal that sought to cease the holding of sessions that lasted until deep in the night.9 The Gran Consiglio and the Cisalpine upper house, the Consiglio dei Seniori, had started their sessions exactly two months earlier, on 22 November 1797. They represented a republic that had been created by Napoleon in June 1797 and that largely comprised present-day Lombardy and Emilia Romagna; they served a constitution that had been imposed on them by the French government and that was a faithful imitation of the French Constitution of the Year III.10 As Antonino de Francesco shows in this volume, this constitution had at first met with resistance amongst radical Italian revolutionaries, but after the coup of 18 Fructidor Year V (4 September 1797) had taken place in Paris, bringing a more radical French regime into power, they joined their more moderate colleagues in embracing the new constitutional order. 20 Joris Oddens and Mart Rutjes Their hopes for a viable and truly independent republic were soon to be crushed. On 22 January 1798, the history of the Cisalpine Republic was not to be written in Milan but in Paris, where the French foreign minister CharlesMaurice de Talleyrand summoned the Cisalpine envoys and presented them with a sixteen-article alliance treaty with France, containing extremely harsh and humiliating conditions.11 After the Cisalpine Directory and its envoys succumbed to French threats and the Gran Consiglio followed this example after ample discussions, the Consiglio dei Seniori refused to ratify the document. The French army responded to this reluctance with force: in April 1798, General Brune, who a month earlier had stood at the basis of the Helvetic Republic but was now the commanding general of the armée d’Italie, purged the Cisalpine Direttorio and both houses of parliament, setting in motion a whole series of coups, all initiated by rivalling French factions.12 22 January 1798: one day in the age of the democratic revolution.13 While the Batavian Revolution was reaching its peak, the Helvetic Revolution was only just getting underway. By contrast, the Veronese revolution, if there had been one at all, was coming to an end, whereas the Cisalpine revolution was taking a dramatic turn. Further southwards, in Naples and Rome, the revolution was yet to begin. From this cross-sectional view of late eighteenth-century revolutionary Europe, it should be sufficiently clear that parallels can be drawn between the revolutions in the various so-called ‘Sister Republics’.14 Recurring elements are the constitutions, the parliaments, the coups, and the French power politics. Similar chains of revolutionary events took place in various parts of Europe, some earlier, some later and in different tempos, but all within a time range of five to six years. While the above account of events merely scratches the surface of the study of the revolutionary era, the past decades have seen many innovative monographs that go far beyond such histoire evenementielle, and that can generally be brought together under the heading ‘political culture’. Almost all of these studies have been written by specialists of the various national, or in some cases regional, revolutionary contexts, who are often equally well-versed in the history and historiography of the revolution in France but know surprisingly little about the history of the ‘other’ Sister Republics. To state it boldly, most historians of the Batavian Revolution have until now most probably been unaware of the fact that 22 January 1798 was not only the day in which Dutch radicals staged a coup in The Hague, but that it also marks the beginning of the revolution in Basel. In this volume, we have therefore brought together experts on the French, Batavian, Helvetic, Cisalpine, and Neapolitan revolutions and their recent historiographies in The political culture of the Sister Republics 21 an attempt to bridge this gap and open up new possibilities to study what we believe should ultimately be seen and studied as one revolutionary sphere. National narratives A question we might f irst ask is whether the citizens of the different revolutionary republics were themselves aware of the political events that occurred in the various Sister Republics. At least when speaking of the Batavian Republic vis-à-vis the Helvetic and the various Italian Republics and vice versa, the answer should most probably be that this was hardly the case. As Andreas Würgler shows in this volume for Switzerland, newspapers and periodicals that had previously focused on news from abroad as a result of censorship restrictions were during the revolution largely filled with domestic political news. With the exception of key events in France – the coup of 18 Fructidor Year V, for example – the public was chiefly interested in the revolutionary events in their own country, which gave them enough to talk about. In the chaotic days following the Dutch coup of 22 January 1798, when the periodicals had trouble keeping up with the domestic news and were printing special issues, the creation of the Helvetic Republic seems to have been the last thing on the minds of Batavian citizens. If politicians knew more than ordinary citizens about what was happening in the other Sister Republics, it was probably not a great deal more. Recent scholarship suggests that the governments of the Dutch, Swiss, and Italian republics have never shown particular interest in establishing multilateral alliances including all the revolutionary republics, preferring instead to invest in ‘bonds of friendship’ with monarchies such as Spain, Denmark, or Sweden when this seemed more opportune. When the Helvetic and Cisalpine Republics were created, for instance, the Batavian government did little to welcome them. It seems to have intended to establish diplomatic relations with the Cisalpine Republic, but while the Cisalpine government sent an envoy to The Hague, no Batavian envoy ever arrived in Milan, and neither did the Batavian government bother to send an envoy to Aarau, from April 1798 the seat of the Helvetic government.15 Occasionally, the governments sent each other declarations in which they confirmed the ideological bonds between the revolutionary republics, but no action was taken to actively strengthen these bonds.16 As a matter of fact, relations between the Helvetic and Cisalpine Republics were even problematic, as the Cisalpine Republic strove to annex the Italophone parts of Switzerland from the beginning of its existence.17 22 Joris Oddens and Mart Rutjes The general state of ignorance or even indifference about the fate of the fellow Sister Republics, caused by a lack of information and the language barrier certainly but above all the self-centredness of the revolutionary nations, never changed after the Age of Revolution ended. Preoccupied as they were with their own pasts, historians from the nineteenth-century nation-states that were built on the foundations of their revolutionary predecessors – the Kingdom of the Netherlands, the Swiss Confederation, and, somewhat later, the Kingdom of Italy – have long focused on questions regarding the place of the revolution in their national Grand Narratives, and the nature of their relation to France during the revolutionary years. This means that those revolutions are mainly treated as a component of the diachronic development of their respective nation-states. The historical analysis of the revolutionary period is therefore dependent on the role that is ascribed to it within the dominant national historiographical narrative. In the case of the French Revolution, its role has been characterized as both positive and negative, but at least as an important episode in the development of the French nation-state.18 Most historians also see the French Revolution as an event that had a transnational and even global influence. No other revolution managed to enforce a break with the early-modern period in such a vigorous way, and its events and ideals are deemed to have had an enormous influence outside the French borders since 1789.19 But such an analysis, correct as it may be, can hardly be called comparative or even transnational, since it is a story told only from the perspective of the French Revolution and how it was received outside of France. Such a Rezeptionsgeschichte is important in understanding the dynamics of the revolutionary era, but it only tells part of the story. When we look at the different national historiographies of the other Sister Republics, we can clearly discern a divergence in the ways the revolutionary era has been judged during the past two centuries; this makes us realize all the more clearly how closely these judgments have been linked to contemporary political circumstances. In the Netherlands, throughout the nineteenth century and well into the twentieth century, the history of the Batavian Revolution of the 1790s and the reformist Patriot movement that had preceded it during the 1780s was mostly written by royalist historians who thought of the anti-Orangist revolutionary era as a ‘French Epoch’ and saw the Dutch revolutionaries either as marionettes operated by French puppeteers or as violent epigones of the French Jacobins of the Year II (1793-1794).20 This negative view became unsustainable during the later twentieth century. Ironically, it was Herman Colenbrander (1871-1945) who paved The political culture of the Sister Republics 23 the way for a revisionist approach by publishing an extensive collection of source material about the revolutionary years, though he himself is mostly remembered for his adherence to the puppet theatre metaphor. In recent decades, historians have increasingly ascribed to the Batavian revolutionaries a mind of their own and credited them as pioneers of the Dutch representative democracy and founders of the Dutch unitary state, while at the same time acknowledging that the Batavian and French Revolutions were deeply intertwined.21 Whereas in nineteenth-century Dutch historiography, one needs a magnifying glass to find historians who embraced the Batavian Revolution, in the contemporaneous Swiss historiography it is harder to find historians who altogether rejected the Helvetic Revolution. Much more than their Dutch counterparts, liberal Swiss historians such as Johannes Strickler (1835-1910) explained the Helvetik as a process of modernization and necessary break with the ancien régime, a view that was sometimes even shared, though with less ardour, by more conservative colleagues. The positive judgement of the Helvetic Era was, however, never unconditional; as in the Netherlands, but less exclusively, there always remained a certain ambivalence about the revolution because of the French military occupation of the Swiss cantons, the political interventions of the French, and the Napoleonic Era that followed the years of democratic reforms.22 In the twentieth century, the way the Helvetic Revolution was interpreted and judged remained strongly linked to fluctuations in the appreciation for the era that had preceded it: a glorification of the Swiss old regime (as well as anti-French sentiments) led to a more critical assessment of the revolution during WWI, while the same happened, though with less intensity, in the 1960s and 1970s when the study of the Swiss ancien régime experienced a revival.23 Interestingly enough, in recent years there has been a tendency to stress the continuities rather than the ruptures between the ancien régime and the Helvetic Republic, while at the same time, in the Netherlands, the conviction that the Batavian Republic should be seen as the most important rupture since Dutch independence has rapidly gained ground.24 The Italian historiography of the revolutionary era has long focused on the relation between the Revolution and the Italian Risorgimento, combining the familiar question regarding respectively the ‘Frenchness’ and ‘Italianness’ of the so-called revolutionary triennio (1796-1799) with another theme that has also been central to both the Swiss and the Dutch historiographical debate: the crucial importance of the revolutionary era for a much longer process of determining whether to opt for a number of independent states, a confederacy of interdependent states, or one centralized unitary state.25 24 Joris Oddens and Mart Rutjes The French ideal of unité et indivisiblité got a grip on all Sister Republics, and all saw internal divisions between unitarists and federalists, but not a single other theme is likely to have been shaped more by the way national historiographies have been embedded in national contexts, and thus by the directions in which the Dutch, Swiss, and Italian states have headed: for a country that went from a confederacy to a unitary state during the Batavian Republic and remained so ever since, or a country for which the Helvetic Republic was a short-lived unitary intermezzo, the historiographical perspective is quite different from that of a country that was formed only in 1870, where the leading question became, in retrospect, whether the seeds of the Italian unification had been sown during the revolutionary years. When, after WWII, the triennio started to be studied more in its own right, the all-absorbing question became whether it had been a triennio giacobino, that is to say whether the ideology of the leading revolutionaries from 1796 onwards was in fact the ideology of the French Jacobins of the Year II, i.e. that of the Jacobin leader Robespierre. As we have seen, nineteenth-century Dutch historians had previously concluded the same about the Batavian revolutionaries. The idea of giacobinismo italiano that was advanced by Armando Saitta (1919-1991) and led to a controversy with – amongst others – Franco Venturi (1914-1994) and Furio Diaz (1916-2011), dominated the debate on the Italian revolution throughout the first postwar decades. The position that the Italian revolutionary movement should be considered a monolithic Jacobin bloc has long remained influential, but more recently a new generation of historians has convincingly shown that in Italy, like elsewhere, there have been different revolutionary ideologies; as a result, the giacobini italiani have become patrioti and the triennio giacobino is now called the triennio democratico.26 The national perspective dominant in history writing has created the inevitable illusion that national developments must have had national causes, because sticking to the national framework has led to a blind spot for the international context.27 This perspective has obscured the fact that many facets of modern European politics, such as representative democracy, constitutions, national citizenship, and civic rights manifested themselves for the first time during the revolutionary era. In this book we want to show how the revolutionary political cultures took root in the different Sister Republics not only within their national context, but specifically how they were influenced by international contexts – if not from one Sister Republic to another, then surely because the revolutionaries in different countries were inspired by the same Enlightenment thinkers – and whether and to what extent the political experiments and experiences of the revolutionary The political culture of the Sister Republics 25 groups in different countries amounted to an international political culture or ideal. The transnational character of the revolutions A volume concerned with the revolutionary political culture of different European territories is comparative and transnational by nature. But such a statement raises all sorts of questions. It raises questions on a methodological level: how should historians go about in writing comparative histories? What does ‘transnational’ mean in the context of the late eighteenth century when most European nation-states had yet to be formed or even ‘imagined’, but when at the same time the revolutions were responsible for the creation of nation-states? It also raises a question concerning the nature of the revolution(s) of the late eighteenth century. Should the upheavals at the end of the ancien régime be characterized as (different) manifestations of a single revolutionary movement, or can we understand the revolutions better if we study them primarily as ‘national’ revolutions? This calls for a brief reflection on the scholarship on the transnational character of the revolutions of the late eighteenth century. Despite the dominance of the national perspective, over the past half-century a number of groundbreaking works have been written in which the revolutions were placed in a broader international pattern, following the argument that ‘this whole [Western] civilization was swept in the last four decades of the eighteenth century by a single revolutionary movement, which manifested itself in different ways and with varying success in different countries, yet in all of them showed similar objectives and principles’.28 This was done most famously by Jacques Godechot and R. R. Palmer in the 1950s and 1960s. Godechot emphasized that the revolutions of the late eighteenth century formed a part of a single ‘Atlantic Revolution’ that swept through Western and Central Europe and the Americas. It was possible to speak of a single revolution because, according to Godechot, the social and economic problems and circumstances that caused it were relatively similar in the different territories where revolution broke out.29 Palmer also saw the different revolutions as part of a larger movement, but he chose to focus more on its ideological coherence. In his view the revolutions were the outcome of a struggle between ‘democratic’ and ‘aristocratic’ groups and ideals, and he concluded that the era under investigation should therefore be called the Age of the Democratic Revolution.30 Although both authors admit that the revolution took different courses and had different 26 Joris Oddens and Mart Rutjes outcomes in specific countries, they stress their basic and fundamental similarities. This book also points to a number of similarities between the Sister Republics, but it focuses more on similarities and differences in political cultures than on social and economic circumstances or on a strict dichotomy between ‘aristocrats’ and ‘democrats’. The transnational perspective as employed by Palmer and Godechot has been far less popular than the national or local focus over the last half-century, but recently scholars have again become interested in linking the revolutionary movements of the Age of Revolutions. Historians are focusing once again on the ‘Atlantic’ character of the revolution,31 but also on its global scope, analyzing how revolutionary ideals and practices jumped back and forth around the globe, stressing reciprocity rather than the unidirectional influence of the American and French Revolutions.32 The international and reciprocal nature of the revolutionary ideals and practices will also be stressed in this volume, but with two important points in mind. First, the Sister Republics were called Sisters for a reason. They were the sisters of the French Republic, who could act as a caring sister but also as a dominant mother. The Sister Republics had been made possible by the French military, and they existed under the French sphere of influence. The Sister Republics had varying degrees of political autonomy, but the power relations were never equal. Though the patriotic governments of the Sister Republics should not simply be viewed as puppet regimes, we have to take the dominant role of France into account when analyzing the political culture of the Sister Republics.33 The second point concerns the geographical scope. The Sister Republics were not so much Atlantic or global phenomena as European ones. Studying the revolutions as part of a ‘European’ revolution is uncommon but, as many of the contributors to this book note, it is highly feasible.34 As mentioned above, revolutionaries in the different Sister Republics and France were mostly preoccupied with events in their own respective countries and often unaware of foreign developments. There were exceptions, however, as Malcolm Crook explains in his contribution. The French politician and ambassador JacquesVincent Delacroix published reflections on the various constitutions that were written at the time in the different republics, and Italian revolutionary Matteo Angelo Galdi called for a federation of sister republics based on France, Holland, and Italy.35 The celebrations that commemorated the foundation of the French Republic in 1798 included the insignia of the Sister Republics, together with a banner proclaiming an eternal alliance between them.36 These examples show the tension during the revolutionary era between the actors’ wish to create new political systems that would fit national cir- The political culture of the Sister Republics 27 cumstances and their belief that their ideals were of a common, enlightened, and universal nature. If these ideals were common, should this be reflected in the cooperation between the European states and to what extent? Or should each revolutionary republic follow its own autonomous path in the realization of the revolution’s ideals? The French had to ask themselves if it was just or even possible to implement their ideals in other countries, as Biancamaria Fontana points out in her discussion of the political thought of Germaine de Staël. Were the French ideals universal enough for all countries, and if so, could they be realized if local people felt that political change was forced upon them by foreign armies? De Staël believed it was not and felt that the very ideal of the revolution, namely self-government, necessarily meant that people had to be convinced rather than forced to accept political change, for any other solution would mean a failure of democratic principles and practice.37 Likewise, the citizens of the Sister Republics were asking themselves whether it was feasible to follow the ‘French model’ and to what extent French institutions reflected supranational ideals that made such an implementation even possible. The international, European context and the tensions within it need to be highlighted to understand the political culture of the Sister Republics. At the same time, this history can offer a historical perspective on current debates on European integration. Comparative and cross-national history In order to understand the nature and dynamics of the political culture(s) of the Sister Republics and the international dimension of their national development, a comparative or cross-national approach is required. Comparative history can be defined as a mode of analysis that is concerned with similarities and differences, explaining a given phenomenon by asking which conditions were shared and which were distinctive, usually, but not necessarily, by comparing different nations.38 Although comparing different national developments is a very apt method for modifying and falsifying specific national explanations for historical developments, there are several problems and pitfalls connected to the comparative method.39 The first problem concerns the broad scope of comparative history: a historian has to be not only a specialist in the revolutionary era on a specific region or country and the specific historiographical traditions and perspectives that differ from case to case, but a specialist on all of them – a task virtually impossible for an individual scholar in today’s highly specialized 28 Joris Oddens and Mart Rutjes and professionalized scholarship. We have therefore invited a range of researchers who are specialized in one of five selected topics with regard to one of the Sister Republics. Each section is preceded by an introduction in which an explicit comparison between the different countries is drawn concerning the topic of the section. This connects to a second problem of comparative history: which unit of comparison is to be chosen, since in principal anything can be compared with anything?40 Since this volume is interested with the nature and development of the political cultures of the revolutionary era, we have taken what we deem the most important elements of these political cultures as our units of comparison. An explanation as to why these specific elements have been selected follows in the next section. A last problem concerns the varying contexts of the regions or countries that are being compared. As mentioned above, there were similar developments within the different Sister Republics, but under different conditions and not at the same time. Whether reforms were instigated in 1795 when the Directoire was in power in France, or in 1801 when Napoleon was tightening his grip on the territories under the French sphere of influence, was of great importance to the success and direction of democratic developments in the Sister Republics. The problem of context here is not only diachronic but also synchronic: the local social and political contexts, not to mention historical developments were very different in the Dutch and Swiss Republics and the different territories in the Italian peninsula. This also means there are conceptual problems to deal with: did Dutch, Swiss, and Italian patriots mean the same things when they used the word ‘democracy’, or were the political circumstances and intellectual traditions so different that their meanings cannot be compared in a useful way?41 This volume is, to a large degree, concerned with exactly this type of question. We try to answer those questions in two ways. First, this book places concepts such as ‘citizenship’, ‘(parliamentary) democracy’, ‘liberty’, and ‘republic’ at the core of its investigations and asks what these elements of revolutionary political discourse (which was often proclaimed as being ‘universal’ by the protagonists) meant in different contexts. Second, although the structure of this book points to a predominantly inter-national comparison, it is complemented with attention for the cross-national transfer of political ideas and practices that highlights the international dynamic of national developments. The contributions in this volume, taking their cue from the perspective of political transfer (whereby the migration of political practices across national borders and their use as examples is studied42), show that The political culture of the Sister Republics 29 revolutionary political thought and practice were not simply the result of a singular intellectual and institutional mould of French fabrication. They were rather the result of a complex process of adaptation and a national reworking of intellectual debates that were international in nature. Revolutionaries all over Europe were in debate over the question which foreign and international ideas and practices could and should be adopted and which ones should be rejected. 43 We should not underestimate the dominating influence of France – as an inspiring example but also as a military force that could and sometimes did force its will on other nations. But it is important to stress that the French governments often let the Sister Republics make their own political choices, resulting in political structures that were a mix of old and new, domestic and foreign. This was caused, on the one hand, by the contingent nature of French foreign policy (in many instances during the revolutionary era, France did not even have a foreign policy), and the fact that many foreign patriots were able to influence French policymaking decisions. 44 On the other hand, French ‘constitution makers’ such as Pierre Daunou were sensitive to the idea that different nations needed different political systems and were therefore also concerned with the question which ‘universal’ ideals and practices should be part of the different constitutions and constitutional drafts of the Sister Republics. 45 The international and transnational focus of this study has helped to test and re-evaluate the national perspective that is commonly used as an explanatory and normative framework for the analysis of the Sister Republics. This becomes clear from most of the chapters in this book, in which many national historiographical accounts of the period of the Sister Republics are debunked. But it also provides new insights into the character of the revolutionary political culture as a whole. For example, what becomes clear from the section on republicanism is that the transformation of early modern republican thought during the revolutionary era was not a process limited to the American and French Revolutions, the countries that are usually studied in this respect. 46 In fact, the elaboration of the hybrid forms of republicanism that were the result of this transformation process was carried out with great conceptual depth and richness in the Sister Republics as well – something that, as Andrew Jainchill notes in his contribution, mainstream historiography of the Age of Revolution has too often neglected. 47 Another example concerns the extraordinary emphasis that all the sister regimes placed on civic education as a means to instill the new republican and democratic values and duties in present and future generations – thus 30 Joris Oddens and Mart Rutjes hoping to guarantee the future of these democratic republics. In the Batavian Republic, the first minister of education stated that ‘the young Citizens and Citizenesses of the State’ should be taught the foundations of the new enlightened regime from an early age, since these foundations were crucial for ‘the durability, maintenance and happiness of the Fatherland, which they should passionately love.’48 These notions and policies were also highly present in the other Sister Republics, and the international perspective employed in this volume shows that it was in fact a vital element central to all revolutionary regimes that were looking for ways to legitimate and perpetuate their political model. 49 The comparative element of this book, then, serves to highlight previously undervalued aspects of the political culture(s) of the Age of Revolution and looks to question some of the national historiographical models of historical explanation by bringing together – in English – knowledge on different aspects of the political culture of the Sister Republics in a systematic way. The political culture of the Sister Republics This volume seeks to study the political world of the Sister Republics from the broad and inclusive perspective of political culture. This means that politics is interpreted as much more than a factual struggle for power and is broadly defined as, in the by now classic words of Keith Michael Baker, ‘the activity through which individuals and groups in society articulate, negotiate, implement, and enforce the competing claims they make upon one another and upon the whole. Political culture is the set of discourses or political practices by which these claims are made.’50 This approach to politics more inclusively interpreted as political culture has been particularly rewarding and illuminating in the research concerning the French Revolution over the past three decades.51 We have gained a deeper understanding of politics and new and valuable perspectives on the political process by studying the way in which political habits, conventions, and styles take shape,52 by researching the way in which politics is embedded in a wider network of communication,53 and by analyzing the forms of argumentation and the meaning of key concepts used by political actors.54 Although this rich research on eighteenth-century political culture has helped our understanding of French political culture, it has had far less influence on the historiography of the Sister Republics.55 This volume hopes to fill this gap and strives to develop a new outlook on the differences and similarities between the various revolutionary states in Europe by applying The political culture of the Sister Republics 31 the fruitful framework of political culture. It does so by exploring five general themes that are deemed to be central to the creation and development of revolutionary political culture. The first section of this book addresses the ways in which modern forms of republicanism emerged in the Sister Republics, all of which were proud to call themselves republics. They therefore placed themselves within the rich tradition of republicanism – an overarching political category during the Age of Revolution. To properly understand the Age of Revolution, as Franco Venturi argued in 1971, historians thus need to ‘follow the involvement, modifications and dispersion of the republican tradition in the last years of the eighteenth century.’56 Following recent trends in historical research, the transformation of republican thought and practice will therefore be at the centre of this section, and the chapters discuss the critical appraisal of the classical and early modern languages of republicanism, the redefinition of republican citizen participation and political virtue, the enlargement of the republican political space, and the uses made of the American and French republican examples. The second part focuses on (additional) political key concepts of the revolutionary republics. The decades surrounding 1800 have been described, among others by the German historian Reinhart Koselleck, as the Sattelzeit in which political key concepts acquired their modern meanings and connotations.57 The culmination of this process of conceptual renewal and transformation coincided with the years of most radical change in other areas of political activity.58 This same pattern can be discerned in the Sister Republics, where similar intense and fundamental debates were conducted over the meaning of political key concepts such as liberty, equality, sovereignty, representation, and citizenship. These debates were particularly urgent because the meaning ascribed to these key concepts would be decisive in the process of creating a new political order. This section deals with the nature of this conceptual change and focuses on the changing meanings of citizenship and democracy/representation, concepts that were central to the most fundamental political change of the time: the development of parliamentary democracies within nation-states. In the third section, the development of parliamentary cultures in the countries under discussion will be investigated. Just like representative democracies, these ‘national’ parliaments (or the attempts to create them) were political novelties, which meant that most aspects of parliamentary culture had to be either invented or copied and adapted, either from former political assemblies or from foreign examples such as the French Assemblée Nationale. The chapters in this section will concentrate on the different 32 Joris Oddens and Mart Rutjes attempts to create national democratic parliaments. They discuss parliamentary rules, rhetoric, and tactics and consider the strategies that were employed when discrepancies between democratic ideology and practice became manifest. Did the activities of these parliaments, the informal parliamentary conventions, the political styles and codes of conduct eventually lead to a modern parliamentary culture? The chapters in part four deal with the interaction between press and politics in the revolutionary states. During the eighteenth century, public opinion developed and was increasingly reflected in a periodic political press. This political press (the forerunner of modern-day political journalism) became a powerful force within the political process of the revolutionary period, helped by the fact that freedom of the press and well-organized public opinion were seen by many revolutionaries as fundamental to the functioning of a representative democracy. This immediately led to debates within the Sister Republics on the limits of free speech and the proper place of public opinion and the role of the press. This section questions to what extent freedom of the press existed, whether openness of government was to be actively sought after, and whether politicians influenced public opinion via the press or whether the people behind the press tried to influence the political process. The book concludes with a section on the relationship between the French Republic and its Sister Republics, and explores recent revisionist insights into this relationship. It will particularly focus on the ways in which the Sister Republics, despite the obvious presence of the French, succeeded in shaping and establishing their own political objectives and arrangements. It also puts the relative success of the Sister Republics in maintaining a degree of independence from France in a comparative perspective. Before beginning with the first section, however, Biancamaria Fontana provides a prologue in which she discusses the views in revolutionary Europe on the future of the European order. Her contribution is a fitting prelude to the story of a revolutionary world – the political world of the Sister Republics.

© Copyright 2025