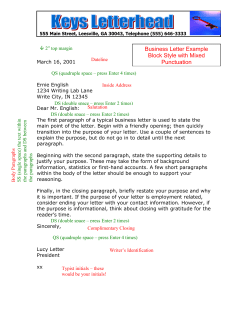

Paragraphs and Essays for College, Work, and Everyday Life