Asian Art Takes a Transnational Turn the assessment

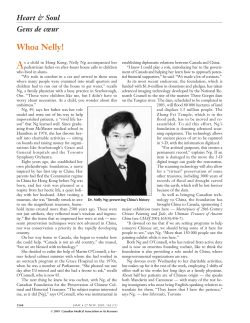

theassessment 40 Asian Art Takes a Transnational Turn Top-end collecting is now largely the accumulation of instantly recognizable, investment-grade trophies. The range of artists regularly offered in evening postwar and contemporary sales at Sotheby’s and Christie’s—which generate most of the market’s headlines—has contracted to a narrow band of 40 to 50 blue-chip Western names, many of them dead. It’s rumored that the bulk of the $1.1 billion spent in November came from wealthy Americans sinking money into Abstract Expressionist classics as a hedge against possible post-fiscal-cliff tax hikes. A similar air of risk aversion now hangs over the world’s top art fairs. Regardless of where on the planet an event takes place, the dominant U.S. and European galleries present selections of works by their familiar (sometimes all-too-familiar) brand artists and give a pronounced occidental slant to the word international. Just at the point when many in the art world are complaining about fair fatigue, a new event this spring in London, may/june 2013 | BlouinArtinfo.comAsia From top: Alexander Ochs Galleries, Berlin and beijing; Christie’s Sea Hyun Lee’s particular brand of globalism, seen in Between Red 162, 2012, evokes the familiar style of Toile de Jouy fabrics in the depiction of contemporary Chinese landscapes. It may be time to look at some basic art world definitions. Take the word international. A serious collector sitting at home in New York or London or Zurich, surrounded by Kapoor, Condo, Wool, Kiefer, and Murakami, probably feels if he bids at Sotheby’s, Christie’s, and Phillips auctions and buys at fairs like Art Basel and Frieze, his taste is already irreproachably international. Pretty well everyone involved in buying and selling contemporary art portrays it as an everexpanding global business. Christie’s reported that buyers at their February sales in London hailed from 33 countries, demonstrating “a truly global appetite for the category.” Yet the exaltation that followed the record $1.1 billion sales total at the three main houses in New York last November masked a creeping conservatism. Both new and existing buyers, chastened by the collapse of the financial market in late 2008 and early 2009, which burst bubbles for Chinese political Pop, Damien Hirst, and others, have retrenched. Sea hyun Lee and Hakgojae, Seoul After years of dominant venues offering a narrow view of international art, new fairs such as Art13 London are broadening buyers’ perspectives by scott reyburn at which about half the artists on view were born outside Europe and North America, offered the chance for visitors to take a wider view. Art13 London was organized by Tim Etchells and Sandy Angus, who cofounded the Hong Kong International Art Fair, and sold a majority stake to Art Basel’s MCH Group in 2011. “We wanted to create a global art fair with a high percentage of dealers who hadn’t shown in the U.K. before,” said Etchells in an interview after the event. “There’s a huge number of international people who live in London who want to see art from all round the world.” Further events in Istanbul and Sydney are planned for September. In London, 129 galleries from 30 countries set up shop under the stately cast-iron roof of Olympia Grand Hall in West Kensington. It was the first time 70 percent of the exhibitors had showed at a London fair, and Etchells’s and Angus’s background in Asia gave the event a distinctive feel. Galleries with spaces in China outnumbered U.S.–based dealers by 3 to 2; South Korea and Singapore each had six booths. Hakgojae from Seoul and Pearl Lam from Hong Kong and Shanghai occupied the prime positions at the front of the event. Conspicuous absences included Gagosian, White Cube, Hauser & Wirth, David Zwirner, Michael Werner, and Pace. “I’m not naming names, but there were certain galleries that I deliberately didn’t invite to Art13,” Etchells says. “If you’re a regular collector, you see the same brands all the time and it’s tedious. I also wanted to appeal to a slightly different audience. There were good-quality people there and very few tire-kickers.” In the run-up to the fair, the organizers carpet-bombed the £1 million-plus residences of Kensington and Chelsea with invitations. If tires were going to be kicked, they would be with handmade Jermyn Street brogues. Private museum owners such as Don and Mera Rubell from Miami, Li Bing from Beijing, and Ramin Salsali from Dubai were among the visitors and contributors to panel discussions. During the show’s run, March 1 through 3, 24,735 people turned up—less than half the attendance of established fairs such as the Armory Show or Art Basel. The most expensive confirmed sale was a Banksy ruined landscape of a Guantánamo Bay captive on a sunset-suffused beach. Priced at £375,000 ($570,000), it was bought by a U.K. collector from the London-based street-art dealer Lazarides. Detractors could easily dismiss this event as a showcase for dealers who can’t get into Frieze, a sort of Salon des Frieze refusés. They might also point out that the inaugural exhibitor list was padded with plenty of midmarket U.K. galleries catering primarily to a domestic audience. “We want to attract more dealers who haven’t been seen in London,” Etchells concedes. “We’ll target more countries so that we can build on the global perspective. We’d like to invite more galleries from Australia, for instance.” BlouinArtinfo.comAsia | may/june 2013 Yet there were plenty of non-British dealers at Art13, particularly from Asia, who’d flown thousands of miles to show works that asked challenging questions about what, exactly, international means in the context of today’s global art market. Many of these works were priced in the $20,000 to $100,000 range, which can be an awkward segment of the market. Wealthy buyers may regard it as too inexpensive to be blue-chip, yet too expensive to make a bet in the hope that it could be the next hot tech stock—or Jacob Kassay. In this price range fell three paintings from the “Collective Memory” series by Chinese artist Chen Shaoxiong, brought by Primo Marella Gallery of Milan and Beijing. Chen, who works in variety of media, is based in Guangzhou, one of the 202 cities in China that McKinsey & Company predicts will have more than a million inhabitants by 2025. Concerned with the psychological effects of urbanization and globalization, Chen uses his fingers to paint fuzzy, newsprint-style dot canvases of familiar landmarks that neatly infuse China’s millennia-old ink-painting tradition with an awareness of Georges Seurat, Roy Lichtenstein, and Gerhard Richter. The paintings Chen made after 2006 of Tiananmen Square and the Olympic stadium in Beijing have a meditative resonance that would have appealed to a writer like the late W.G. Sebald. But at Art13, Primo Marella was showing more recent finger-painted dot canvases of Venice, priced between €20,000 and €25,000 ($26–32,000). Quite what La Serenissima has to do with the Chinese collective memory remains obscure, but a painting of Palladio’s Il Redentore church found a buyer during the fair, underscoring Chen’s success in appealing to an international audience. Primo Marella is one of many globally-minded dealers who are betting that China 41 Earth, Ink & Fire, 2013, above, an installation combining the Song-style bowls of Korean artist Young-Jae Lee and hangings by Chinese ink painter Chen Guangwu, was sold at Art13 by Alexander Ochs Galleries, of Berlin and Beijing, for $65,000. Song Hyun-Sook, whose 17 Brushstrokes, 2002, left, earned $39,000 at Christie’s last November, nods to the West in her use of tempera on canvas while alluding to the Asian calligraphic tradition in her style. theassessment undergone internationalization. Uniform, recognizable, and with a secondary market easily trackable on Artnet (15 entries, top price $56,000), Lee’s stylized landscapes are cropping up at more and more of the world’s 200 art fairs. Hakgojae of Seoul found buyers for two at Art13, priced at £22,750 and £14,300 ($35,000 and $22,000). Lee’s formulaic but commercial vision made an instructive contrast in Hakgojae’s booth with two paintings by another Western-trained Korean artist, Song HyunSook. Song worked as a nurse in Germany in the 1970s before studying at the College of Fine Art in Hamburg. She paints austere canvases inspired by her childhood in rural South Korea. Unusually, these abstracted closeups of farmhouses, ceramic pots, wooden posts, and hanging ramie fabric are rendered in the Western medium of tempera, but with the broad sweeps of the Asian inkpainting tradition. Works are titled according to the number of strokes they take to complete. 12 Brushstrokes over 2 Brushstrokes, a canvas featuring the artist’s favorite motifs of hanging ramie and a wooden post, was being haggled over as the fair closed. Hakgojae was asking £21,450 ($28,000). Song’s secondary-market prices reached $HK300,000 ($39,000) at auctions in Hong Kong last year. Lee and Song were each in their own way definingly representative of the two strands of globalism running through Art13. Both artists, in their different ways, fuse East and West, old and new. Lee’s paintings, cannily commoditized, brashly colored, and conceptually knowing, have all the ingredients of Western-style international art. By contrast, Song’s gentler, more contemplative paintings refract a contemporary Minimalist aesthetic through the age-old calligraphic tradition. This art, with its technique more firmly rooted in the East, might be characterized as transnational. The Collins dictionary clarifies the distinction. International, adj.: Of, concerning, or involving two or more nations or nationalities. Transnational, adj.: Extending beyond the boundaries, interests, etc., of a single nation. may/june 2013 | BlouinArtinfo.comAsia “Asian artists are definitely returning to a more minimal, less ostentatious aesthetic,” says London-based art adviser Arianne Levene, who noticed a number of works that express new ideas with old techniques. “It feels appropriate for the world we live in today. Political Pop was very 1990s and 2000s. That felt right at the time.” Levene was one of the many Western advisers, dealers, and collectors who were impressed by the sheer distinctiveness of Art13. “I was pleasantly surprised,” Levene added. “There were some serious galleries from Asia who brought subtle, unexpected things. We don’t have any other fair in London that shows these kinds of artists. I hope they build on the international element.” The subtle, Minimalist strain of transnational art was also on show at the booth of New York and New England dealer Cynthia Reeves. She was offering the abstract ink paintings of Shen Chen, a U.S.–trained Chinese artist who divides his time between New York City and Beijing. Two of Chen’s canvases, the sort of works Rothko would have made if he’d taken up traditional Chinese ink painting, sold at the fair for $28,000 and $22,000. Alexander Ochs Galleries of Berlin and Beijing presented Earth, Ink & Fire, a refined collaborative installation of more than 200 monochrome Song Dynasty–style bowls by the Korean artist Young-Jae Lee, set on the floor in front of abstract hangings by the Chinese ink painter Chen Guangwu. It was snapped up by an Italian collector for €50,000 ($65,000). “You can no longer use the Western aesthetic to evaluate this art,” said Pearl Lam, who was showing works by the Chinese painters Zhu Jinshi and Su Xiaobai, both of whom studied in Germany and have established secondary markets in Asia, if not the West. Lam sold six of Zhu’s massively impastoed abstracts for up to $150,000, while two of Su’s lacquered color field paintings found buyers at up to $250,000. Pearl Lam galleries, Hong Kong and Shanghai 42 will eventually produce a new generation of contemporary-art collectors. They are also backing Africa as a growth market. The 2013 blanket triptych, Tibet, by Mali’s leading artist, Abdoulaye Konate, was given pride of place at the front of its booth at Art13. At the moment China is suffering from a shortage of contemporary-art collectors. After the crash of 2008, many of them migrated from names like Yue Minjun and Zhang Xiaogang into what they regarded as the safer haven of modern art. The early 20th-century calligrapher Qi Baishi became the most expensive Chinese “contemporary” artist when a 1946 scroll painting of his sold for RMB425.5 million ($65 million) at a 2011 auction in Beijing. “Young Chinese artists lack support from wealthy local collectors,” said Michela Sena, director of Primo Marella’s Beijing gallery. “Now Chinese contemporary art is required to be really international. The works have to speak a global language, be generally understandable and not local anymore. Only a few artists achieve this. Many from the past generation who are too restricted in their localism just disappear.” There is a new generation of Chinese contemporary artists, not particularly well represented at Art13, who have become instant internationalists. Liu Diu, for instance, makes digitally enhanced photos of giant amphibians running amok in Chinese megacities. The danger is that internationalization can lead to an artist’s losing the sense of place that originally made him interesting. As Seneca put it in his Moral Letters to Lucilius, “To be everywhere is to be nowhere.” At the moment, Chen Shaoxiong has just nine entries on Artnet, with a top auction price of $35,467. It’s not difficult to imagine him producing dot paintings of the most famous sights in the world, churning out global collective memories of the Statue of Liberty for the Armory Show, of Big Ben for Frieze London, and becoming rich in the process. This is rather like the moment in 2011 when the Indian artist Subodh Gupta cast limited-edition bronzes of Duchamp’s mustachioed L.H.O.O.Q. Mona Lisa rather than making sculptures out of the tiffin tins used in his village of Bihari. Great career move—one of the bronzes was bought by billionaire collector François Pinault—but what has been left behind? The Korean painter Sea Hyun Lee—who trained at London’s Chelsea College of Art and Design and produces monochrome inundated landscapes reminiscent of 18th-century porcelain and toile fabrics— is another artist who has From top: Chen Shaoxiong and Primo Marella Gallery, Milan; Cynthia-Reeves, New York Presented at Art13 by Milan-based Primo Marella Gallery, Chen Shaoxiong broadened the audience—and the market—for his “Collective Memory” series when he began employing his finger-painting technique to depict landmarks beyond China’s borders, such as in this 2012 view at right of a Venetian church by Palladio. Taking a subtler approach to blending diverse traditions, Shen Chen’s acrylic on canvas 42222-12, 2012, below, was brought to the fair by Cynthia Reeves, of New York and New England. BlouinArtinfo.comAsia | may/june 2013 For all Lam’s claims that these painters are beyond the ken of Western aesthetics, both are big on wall power in a very Western kind of way, and Su’s market has benefited from her training with Richter, the ne plus ultra of international artists. Su’s lacquer abstracts have climbed to prices as high as $355,000 at auctions in Asia. “Fairs like Frieze are too Eurocentric,” says Lam. “They want to define what is international, and that definition is American and European. Western Conceptual art loves to take political and economic positions. This is not so much the case in our culture. Chinese art is all about enhancing oneself internally.” Lam has a point. Asian culture is built on the intellectual bedrock of Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism. All are contemplative disciplines of thought that revere tradition, continuity, and a sense of personal growth within a communal context. Western culture, at least for the past 200 years, celebrates individualism, iconoclasm, subversion. Which view will prevail in the little world that is the global art market? (It’s salutary to remember that the entire value of the planet’s auction and dealer sales last year was valued by the European Fine Art Foundation at $56 billion, while Facebook is worth $60 billion.) At the moment, it is Westerners who organize the major contemporary art fairs in Asia, as well as in the U.S. and Europe. As Art13 exhibitor Ochs put it, “We have new broader markets, but the new art markets haven’t developed with them.” Meanwhile, international people continue to fly round the world to stay in international hotels to visit international art fairs where international galleries show international art that is explained in International Art English (IAE). There has always been an implicit, slightly colonialist assumption among American and European auctioneers, dealers, curators, and collectors that sooner or later the booming economies of Asia, with their fast-growing populations of high-net-worth individuals, will finally recognize the innate superiority of Western contemporary art. This epiphany has yet to happen. If it had, Sotheby’s and Christie’s would be holding auctions of Western contemporary art in Hong Kong, as they do with wine. This situation may well change. Thousands of students from China and other Asian nations are attending universities in Europe and North America and are being exposed to Western art. “A new generation of young Chinese collectors is growing up,” says Sena of Primo Marella. “They are starting to approach Western contemporary art, and I suppose that they will soon build interesting collections updated with an international taste.” The question is whether Western-style internationalism will become the mainstream of Asian collecting taste or growing economic and political power will give the region greater confidence in its own ways of thinking. What will happen, for instance, when entrepreneurs from China, Malaysia, and Korea start to organize their own contemporary art fairs? At the moment, the Christopher Wools and George Condos on your walls are worth 10 times more than Chen Shaoxiong, Sea Hyun Lee, Song Hyun-Sook, and even Zhu Jinshi. That might not be the case in 10 years’ time. 43 Shown by gallerist Pearl Lam, of Hong Kong and Shanghai, Zhu Jinshi’s impastoed abstractions, such as Children’s Dreams, 2012, were reported to be the first stop on tours of Art13 by art advisers from the fair’s sponsor, Citi Private Bank.

© Copyright 2025