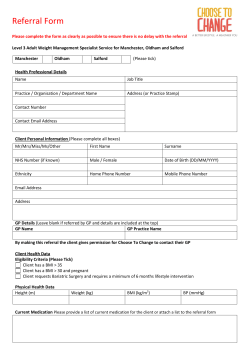

FOR HEALTH PROFESSIONALS