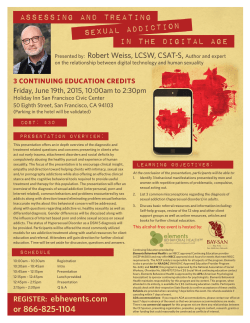

ABSTRACT EDUCATION FOR PROFESSIONALS ON