A Critique of the ACT Light Rail Business Case

A Critique of the ACT Light Rail

Business Case

24 Mar 2015

Leon Arundell B. Sc. Hons., M. Env. St., Grad. Dipl. Appl. Econ.

Critique of the ACT Light Rail Business Case

Page 1 of 17

About the author

Leon Arundell has tertiary qualifications in science, environmental studies and economics. He has worked in the alternative fuels and travel demand management areas of the Australian Greenhouse Office, at the Canberra Bicycle Museum, and for Pedal Power ACT. He founded Living Streets Canberra, and has served on the transport subcommittees of the Conservation Council ACT and of the Combined Community Councils of the ACT.

He conducted his first cost benefit analysis in 1979.

Acknowledgements

I thank Dr Leo Dobes, Max Flint, Max Kwiatkowski, Jim Wells, John L Smith, Geoff Davidson, Chris Emery and others who provided feedback and comments on the analysis. The views expressed in this paper are my own.

Leon Arundell, February 2015.

Notes

1. Except where otherwise indicated, page numbers and table numbers refer to the full Capital Metro Business Case.

2. Costs are quoted in present values (discounted to 2014) dollars, except for costs quoted from the ACT Government's 2012 Proposal to Infrastructure Australia which are in 2011 dollars.

Critique of the ACT Light Rail Business Case

Page 2 of 17

Contents

Correction ..................................................................................................................................

4

Discussion .................................................................................................................................

4

Main findings ............................................................................................................................

6

Issues .........................................................................................................................................

7

Bus rapid transit vs. light rail ...............................................................................................

7

Base case ..............................................................................................................................

7

Transit lanes ..........................................................................................................................

7

Data and estimation methods ................................................................................................

9

Costs .....................................................................................................................................

9

Benefits .................................................................................................................................

9

Travel time savings ..........................................................................................................

9

Agglomeration benefits ...................................................................................................

9

Bus, car and rail operating costs ....................................................................................

10

Land Use Benefits ..........................................................................................................

10

Wider economic impacts ...............................................................................................

10

Greenhouse emissions and other externalities ...............................................................

10

Tax benefit from increased labour supply .....................................................................

10

Attachment 1: Consideration of transit lanes and bus lanes ....................................................

11

Attachment 2: Table 58: Externality benefits (cents per km) .................................................

12

Critique of the ACT Light Rail Business Case

Page 3 of 17

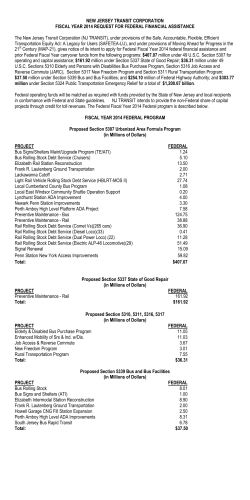

Correction

New evidence,obtained on 25 February 2015, indicates that:

• the claim at p.51 of the Business Case that “the total car travel time from Gungahlin to the City during morning peak averages approximately 35 minutes” is actually plausible in relation to a half hour “peak” for cars that leave Gungahlin between about 8 am and 8.30 am, and;

• the implied free flow travel time of 27.2 minutes is highly inaccurate. This travel time is implied by

(a) the claim at p. p.51 that “the total car travel time from Gungahlin to the City during morning peak averages approximately 35 minutes” and (b) the claim at p.52 of 7.8 total “minutes lost per vehicle due to congestion between points along the route in peak (compared to free flow conditions).”

This is shown by the results of the author's following timed drives along the route:

Date

Depart Gungahlin

Travel time (minutes)

Estimated congestion delay (minutes)

Thursday 25 Feb 2015

7.02 am

15

0

Thursday 25 Feb 2015

7.36 am

22

7

Thursday 17 May 2012

7.40 am

19

4

Friday 18 May 2012

8.01 am

25

10

Thursday 11 Feb 2015

8.01 am

35.5

20.5

Thursday 25 Feb 2015

8.24 am

35

20

Discussion

This is a critique of the undated “Capital Metro Full Business Case” that was prepared by the Australian Capital Territory Government's Capital Metro Agency and published in October 2014.

Any proposal to spend hundreds of millions of dollars warrants close scrutiny.

The key question for the proposed GungahlinCivic light rail projects is, “does Capital Metro's 2014 Business Case provide confidence that a decision to build light rail would be justified?”

The financial case.

This project cannot be justified on purely financial grounds. The Business Case estimated costs at $823 million (Table 18) and fare revenues at only $81 million (Table 46).

The economic case.

Critique of the ACT Light Rail Business Case

Page 4 of 17

Evaluation of the economic case requires assessment of the financial and nonfinancial costs and benefits of the project.

Some nonfinancial benefits can be readily quantified and expressed in dollar terms – for example changes in trip times, which can be converted to dollar values using factors that are commonly used, even if those factors are not universally agreed.

Some nonfinancial benefits are more difficult to quantify, and/or to express in dollar terms – for example, urban separation (Attachment 2) and agglomeration benefits.

The Business Case has done an admirable job of identifying and quantifying the financial and nonfinancial benefits of the light rail project, including many benefits that might otherwise be regarded to be intangible and unquantifiable. However it has omitted some costs and doublecounted some benefits.

An important question is “does Capital Metro's Business Case provide confidence that a decision to build light rail would be a better decision than the alternative decisions?”

The clear answer to this question is “no,” in relation to both of the principal “alternatives” of a bus rapid transit system, and extension of the existing bus lanes.

The Business Case provided no argument to support the proposition that the additional $338 million cost of light rail, relative to a bus rapid transit system, would be justified by its additional $60 million worth of benefits.i

Nor did it argue that the approximately $500 million additional cost of light rail, relative to bus lanes, would be justified by its additional benefits.

The fundamental question is, “Did the Business Case demonstrate that the benefits of light rail will make the costs worthwhile?”

The Business Case answered this question in the affirmative by estimating that light rail would have a benefit to cost ratio of 1.2. But the the lack of information about how the Business Case estimated costs and benefits, together with the magnitude of errors in the information that the Business Case did provide, raise genuine doubt about the validity of that conclusion.

The political case

The ACT Government's decision to proceed with light rail rather than bus rapid transit appears to be a political decision based on a belief of “high community support for LRT and that LRT is viewed as a long term transport solution within the Project Corridor”ii rather than on the Government's own assessment that “BRT is projected to deliver higher economic returns. … the economic returns that can be delivered through LRT investment alone are likely to be economically marginal and the net economic outcome for LRT under even minor adverse circumstances is likely to result in negative economic returns.iii

Consistent with the above belief, the Government did not evaluate the costs and benefits of converting existing lanes to transit lanes or bus lanes, and did not present them to the public either as interim or as long term options. The Government's 2012 Submission to Infrastructure Australia summarily dismissed the benefits of bus lanes and transit lanes.1

1

For a discussion of the Government's assessment of transit lanes, see Attachment 1.

Critique of the ACT Light Rail Business Case

Page 5 of 17

The chosen median alignment requires the construction of two additional traffic lanes for public transport. It is not clear whether, or to what extent, the purpose of proposing the median alignment was to find a politically acceptable way to provide additional space for general road traffic.

Critique of the ACT Light Rail Business Case

Page 6 of 17

Main findings

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Bus rapid transit is a better investment than light rail.

After adjusting for partial double counting of travel time benefits, the net benefit of light rail falls below zero.

The Business Case counted agglomeration benefits twice – in Wider Economic Impacts, and as Land Use Benefits. It overstated public transport patronage, onroad travel times, and travel time savings to public transport.

Lack of information in the Business Case makes it difficult to determine whether errors were made in the estimation of many of the costs and benefits and, where errors are identified, to quantify the impacts of errors.

The Business Case overestimated the benefits of light rail, because it assumed that the Government would not use transit lanes to address increasing congestion delays to public transport.

Transit lanes will provide public transport travel time benefits comparable to those of light rail, at a capital cost of about $16 million.

Travel time savings for car commuters will be comparable to those for tram users. Reduced car travel times will encourage more car commuting, which will in turn reduce light rail patronage, increase greenhouse emissions and create more pressure to convert valuable CBD properties to car parks.

The Business Case did not explain how it estimated that buses have greater greenhouse, noise, air pollution, water pollution, urban separation and road damage benefits than light rail.

Critique of the ACT Light Rail Business Case

Page 7 of 17

Issues

Bus rapid transit vs. light rail

“[Bus Rapid Transit] is projected to deliver higher economic returns.

On the other hand, the economic returns that can be delivered through {Light Rail Transit] investment alone are likely to be economically marginal and the net economic outcome for LRT under even minor adverse circumstances is likely to result in negative economic returns.”

ACT Government City to Gungahlin Transit Corridor Submission to Infrastructure Australia, 2012.

That submission estimated that bus rapid transit would provide net benefits of at least $243 million, at a benefit to cost ratio of at least 1.98.iv

Capital Metro's 2014 Light Rail Business Case confirmed that Bus Rapid Transit is a better investment than light rail, estimating that light rail offered a net benefit of only $121 million, at a benefit to cost ratio of only 1.2 (Table 18).

Base case

The Business Case used a “do nothing” base case that returned higher net benefit estimates than “business as usual.” v The Business Case incorrectly described “do nothing” as the 'likely situation'.

A more likely situation is that, faced with the prospect of GungahlinCivic commute times increasing by 22 minutes (p.51), the Government will implement low cost high return measures such as extending the existing bus lanes or converting some road sections to transit lanes.

Transit lanes

Unlike light rail or busways, transit lanes can be built and upgraded progressively, and in time to help the Government meet its commitment to increase the public transport journey to work mode share to 10.5% by 2016vi. They can be introduced as short T2 lanes (minimum 2 people per vehicle) in high priority locations such as the approach to Wakefield Avenue, and subsequently extended and/or upgraded to T3 lanes or busonly lanes.

On the basis that transit lanes cost one fiftieth the cost of light railvii it would cost about $16 million to build transit lanes between Civic and Gungahlin.

Removal of low occupancy vehicles from transit lanes has both direct and indirect impacts on congestion:

• The direct impacts are to reduce congestion in the transit lane and increase congestion in the remaining lanes.

• Reduced congestion in the transit lane will directly improve bus travel times and indirectly increase bus patronage, because “improving public transport travel times is the most important factor in encouraging greater use of public transport.”viii

Critique of the ACT Light Rail Business Case

Page 8 of 17

Increased congestion in the remaining lanes, combined with the attraction of faster travel times for passengercarrying cars, will indirectly reduce congestion by encouraging multiple occupancy car use. The historical evidence shows that the congestionreduction, pollution reduction and greenhouse emissions reduction impacts of increased walking, cycling and public transport patronage in the ACT have been more than negated by reductions in numbers of cars carrying passengers.ix Transit lanes offer the promise of reducing car numbers, and their consequent congestion, greenhouse and pollution impacts, by encouraging people to travel more than one per car.

• Increased congestion in the remaining lanes can be addressed if necessary by adding a short additional lane at the approach to and exit from each signalised intersection, as is the practice on arterial roads in Melbourne. An extra lane allows more vehicles through during each green signal phase. The extra lane can merge with the adjacent lane after the traffic has accelerated to normal speed.

There are currently two sections of bus lane on the GungahlinCivic route – a 1.3 km section between Sandford Street and the Federal Highway, and a 120 metre section at the approach to the Barton Highway intersection.

The travel time benefits of these bus lanes will increase in future, as congestion increases in the adjacent general traffic lanes. Travel time savings currently attributable to these transit lanes can be estimated in several ways. For example:

(1) A “current average Gungahlin to City morning peak [car] travel time of approximately 35 minutes,” combined with an average AM peak scheduled bus trip duration of 27 minutes (calculated from route 200 series timetables), imply that the existing bus lanes reduce travel time by more than twelve minutes;

(2) The 1.5 km of bus lanes cover 12.5% of the route, and so can be expected to reduce travel times by 12.5% of the 7.8 minutes of congestion delays – i.e. 1 minute;

(3) These bus lanes cover 15% of the traffic signals along the route, and so can e expected to reduce travel times by 1.2 minutes;

(4) The average AM peak scheduled bus trip duration of 27 minutes compares with a typical offpeak travel time of 22 minutes. This indicates that congestion on the 10.5 km of nonbuslane sections adds five minutes to the trip duration, and so extending bus lanes to the entire route would reduce current bus travel times by five minutes.

Transit lanes or bus lanes are unlikely to eliminate the entire 22 minutes of future congestion delays, because of the likelihood of some congestion within the transit or bus lanes.

Assuming that transit lanes or bus lanes extend for the whole of the route, reduce current congestion by five minutes per AM or PM peak trip, and reduce future congestion delays by eleven minutes per AM or PM trip, then they will provide travel time benefits of 16 minutes per AM or PM trip. For the 10,205 peak commuters in 2031 they will save 2,721 hours per day. This is two thirds of the 4,033 hours per day (p.74) that the Business Case projects for light rail, and more than this critique's 1,871 hours per day estimate for light rail.

•

Critique of the ACT Light Rail Business Case

Page 9 of 17

Data and estimation methods

The Business Case:

• overstated public transport patronagex and onroad travel timesxi by more than thirty per cent;

• withheld not only the information that it used to estimate costs, and the methods by which it estimated costs and benefits (p.20), but also the identities of all the advisors engaged on the projectxii;

• failed to explain why it did not use consultants' analyses for which Capital Metro had paid more than $150,000, but instead used analyses prepared by Capital Metro staff;

• did not explain the workings of the “strategic (macro) modelling … [which] considers landuse models to predict the volume of demand and travel patterns” to estimate “economic benefits” (Footnote, p.51). Nor did it test the modelling results by benchmarking them against the micro simulation results reported at p.51.

Costs

The base case did not provide enough information to permit the validity or accuracy of its cost estimates to be evaluated.

Cost estimates can be subject to significant error. For example in October 2010 the ACT Government announced that the Civic Cycle Loop had topped the Government's priority list. It subsequently published the report on which that announcement was based. That report estimated the cost of the Civic Cycle Loop at $180,000, A subsequent Walking and cycling feasibility study reestimated the cost of the Civic Cycle Loop at $6 million.

Benefits

Travel time savings

The Business Case doublecounted $168 million of travel time savings, by also adding them as land value increases.xiii After adjusting for this error, the net benefit of $121 million becomes a net cost of $10 million, and the benefit to cost ratio falls to 0.99.

The Business Case did not explain how it derived its highly implausiblexiv estimate of 4,033 hours per day of travel time savings to public transport. Nor did it state its estimates of travel time savings to car commuters, even though those savings will be comparable to savings to to public transport.xv

Agglomeration benefits

Some agglomeration benefits have been counted twice. They are included as a component (Table 26) of the $72 million of urban densification benefits (Table 27) that contribute to Land Use Benefits, and also as a separate $165 million component of the $198 million Wider Economic Impacts (Table 28).

Critique of the ACT Light Rail Business Case

Page 10 of 17

Bus, car and rail operating costs

“Total vehicle operating costs comprise basic running costs of the vehicle (depreciation, fuel, repairs and maintenance) in resource cost terms (i.e. excluding taxes and duties)” (p.97).

Tables 56 and 57 state that the operating (resource) costs for cars are 6.8 cents per kilometre, and the operating costs for rail and buses are 6.1 and 5.1 cents per kilometre, respectively.

These estimates are 85% below the NRMA's estimates of total running cost for medium cars.2

Land Use Benefits

Land use benefits (Table 25) seem to include all additional land uses within the light rail corridor as benefits of light rail, including land uses that in the absence of light rail would have occurred outside the light rail corridor but within the ACT.xvi

Wider economic impacts

Wider Economic Impacts (Table 28) do not include the Marginal Excess Tax Burden, or deadweight loss, that will be imposed on the ACT economy if rates or taxes are increased to pay for the light rail. Increase in taxation, or other reduction to disposable income, has a depressing effect on the economy. If a 20 percent figure is used, then the total financial cost of the project should be multiplied by 1.2.

Greenhouse emissions and other externalities

The Business Case not explain how it estimated that buses have greater benefits than light rail to greenhouse noise, air pollution, water pollution, urban separation and road damage (Attachment 2). Nor did it explain how (if at all) those estimates were incorporated into the cost benefit analysis.

Capital Metro has advised that the Business Case did not consider greenhouse emissions from light rail construction. Emissions due light rail construction have been estimated at 54 g CO2e per passenger kilometre travelled.xvii

Tax benefit from increased labour supply

The $31m estimated tax benefit from increased labour supply does not seem to allow for the costs of providing municipal services to those additional workers and their families. If the “tax benefit” is a way of paying for those services, rather than a “profit” to the ACT, then cost of providing those services should be subtracted from the $31m.

If this tax is received by the Australian Government rather than the ACT Government, then it is arguable that it should be excluded from consideration.

2

Car annual running costs , divided by 15,000 km per year: http://www.mynrma.com.au/motoring

services/buysell/buyingadvice/caroperatingcosts.htm, accessed 9 February 2015.

Critique of the ACT Light Rail Business Case

Page 11 of 17

Attachment 1: Consideration of transit lanes and bus

lanes

Table 22 of the ACT Government 2012 City to Gungahlin Transit Corridor Submission to Infrastructure Australia:

Commentary:

1. “short term relief” presumably refers to the problem that the number of cars and buses that use a transit lane or bus lane will increase over time. This problem can be addressed by progressively changing the transit lanes from T2 to T3 or T4, changing them to busonly lanes. If necessary, buses can use the adjacent general traffic lanes to overtake.

2. “may cause congestion:” transit lanes reduce congestion in the transit lane. Any resulting congestion increases in other lanes can be ameliorated by adding a short additional lane at the approaches to and exits from choke points such as signalised intersections. These lanes will increase the number of vehicles that can pass through the choke point in a given period, such as a green traffic signal phase.

3. “increase through traffic on north Canberra suburban roads” see above.

4. “tend to be ineffective … as they require manual enforcement [as do most of Australia's 300plus road rules] and hence suffer from high violation rates.” No evidence is offered to support the contention that violation rates are “high” or to indicate whether the consequences of violation rates are significant.

5. “transit lanes are unlikely to address in full current or future bus operating issues.”The same applies to bus lanes, busways and light rail.

6. “cause congestion along Northbourne Avenue:” See point 2 above.

Critique of the ACT Light Rail Business Case

Page 12 of 17

Attachment 2: Table 58: Externality benefits (cents per km)

Critique of the ACT Light Rail Business Case

Page 13 of 17

i

ii

iii

iv

v

vi

vii

viii

Relative costs and benefits of light rail and bus rapid transit are backcalculated from the 2012 results given in Table 10: Economic Results for Project Options of the 2012 Submission to Infrastructure Australia.

ACT Government 2012 City to Gungahlin Transit Corridor Submission to Infrastructure Australia, Table 22.

ACT Government 2012 City to Gungahlin Transit Corridor Submission to Infrastructure Australia, p.29

ACT Government 2012 City to Gungahlin Transit Corridor Submission to Infrastructure Australia, page 29.

“The base case scenario represents the likely situation if the project does not proceed. It assumes that only already approved and planned changes to road and bus networks occur.” (p.77). For a discussion of this, see The Canadian Treasury Board's CostBenefit Analysis Guide (Cost–Benefit Guide: Regulatory Proposals, Treasury Canada, 2007: http://sciencepolicy.colorado.edu/students/envs_5120/CanadaCBA.pdf ) explains:

“An important element of the assessment is ensuring that the baseline scenario is properly defined. The baseline situation does not necessarily mean that nothing will happen to the current situation over time if the policy is not implemented. Business will go on as usual and the resources of the economy will be allocated according to the forces of the market within the existing legal and regulatory environment. Over time, there will almost certainly be innovation and technological progress. Some of these changes may improve in the baseline scenario, while others may exacerbate the problem. To the degree possible, the impact of the technological changes that are in the pipeline, but not necessarily in the market, should be incorporated into the baseline scenario.

...It is this optimized baseline scenario that should be compared to the “with policy” scenario in order to calculate the incremental benefits and costs over the life of the regulation. It is not correct to compare a nonoptimized baseline scenario to an optimized “with policy” scenario, as this will overstate the incremental net benefits attributable to the regulation.”

The Government's election commitment of “increasing the public transport share of all work trips to 10.5% by 2016” was made in “ACT Labor’s plan to invest $37 million to transform public transport” on 15 October 2012. At the 2011 Census the public mode share was 7.8% well below the Government's 2004 sustainable Transport Plan target to increase the public transport mode share target from 6.7% in 2001 to 9% by 2011. A Canberra Times article ACTION patronage falls reported on 12 February 2015 that “So far in 201415, ACTION recorded 8.9 million passenger boardings.” The indicated 17.8 million boardings for the full year would represent a nominal 14% increase on the 17.6 million boardings recorded in 201011 (ACTION annual report), but a decrease of more than 4% after allowing for population growth.

Capital cost per mile of Bus on Arterial $US0.68m, which is one fiftieth the $US34.79m cost per mile of light rail: Currie, G, 2009, Research perspectives on the merits of Light Rail vs Bus, BITRE Colloquium Canberra 1819 June 2009, p.37: http://www.infrastructureaustralia.gov.au/publications/files/LightRailVSBus.pdf “The Transport Elasticities Study shows that improving public transport travel times is the most important factor in encouraging greater use of public transport.” The Sustainable Transport Plan for the ACT, ACT Government, 20014, p.19.

ix

x

xi

xii

xiii

For discussions of the impacts of reduced travel as car passengers, see How Canberra's Sustainable Transport Plan increased car dependence and changes in journey to work mode shares. (Living Streets News, November and December 2014.

The Business Case stated at p.50 that “The public transport commuter mode share across the whole of Canberra is … 11%.” The ACT public transport commuter mode share at the 2011 Census was 6.7% according to Quickstats, which is based on place of usual residence. A figure of 7.8% can be calculated from the Place of Enumeration Profile. ACTION bus trips per head of population have decreased since 2011. The Canberra Times reported on 12 February 2015 that “So far in 201415, ACTION recorded 8.9 million passenger boardings, well below the 9.3 million target for the halfway point of the financial year.”

The Business Case at p.51 refers to a “current average Gungahlin to City morning peak [car] travel time of approximately 35 minutes” and in Table 9 it states that the average congestion delay is 7.8 minutes. These figures imply a travel time of approximately 27.2 minutes in free flowing traffic.

But Google Maps estimates a travel time of 17 minutes, a timed drive of the route took only sixteen minutes, and even scheduled bus travel times (which allow for stopping at bus stops) are only 19 minutes for services that depart after 7.30 pm.

Leon Arundell's three timed AM peak drives from Gungahlin to Civic averaged only 26.5 minutes, departing Gungahlin 7.40 am on 17 May 2012 (19 minutes), 8.01 am on 18 May 2012 (25 minutes) and 8.01 am on 11 February 2015 (35.5 minutes).

Although the Business Case withheld the identities of all its contributing advisors, several are named in the April 2014 Project u

pdate 5 and it is public knowledge that Capital Metro “engaged Ernst and Young (EY) as the commercial advisors for the Capital Metro project with the initial objective of assisting in the delivery of a business case for the Capital Metro project and all necessary preliminary works” paid them more than $150,000. (Source: Capital Metro Annual Report 201314, pp.12,105: http://www.capitalmetro.act.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0020/644105/CapitalMetro

AnnualReport.pdf).

“Increases in land values largely reflect benefits such as travel time savings, which are already incorporated in the government's cost benefit analysis. To include them again is double counting.” Former manager of major project analysis for ACT Treasury David Hughes, Canberra Times, October 14, 2014.

“Doublecounting occurs because increased property prices only occur due to the perceived benefits of reductions in costs. Prices would not rise otherwise.” Adjunct associate professor Leo Dobes of the ANU Crawford School of Public Policy, Canberra Times, 16 July 2014.

xiv

Commuters who reap travel time savings from the light rail would be prepared to pay higher prices for property or for rents within the light rail corridor. For example, If the travel time savings of a particular location are worth $22 per week, people might be prepared to pay an extra $16 per week in rent or in loan repayments. They will still be $6 ahead, and the extra $16 will increase the value of the property. The value of travel time savings is the net personal benefit plus the consequent increase in land values. The value of travel time savings includes a least part of the land value increases. The Business Case estimates value of travel time savings at $222 million and the resulting land value increases at $168 million. This indicates a net personal benefit of $222m $168m = $54m. Instead of adding this $54m to the increase in land values, the Business Case adds the entire $222m.

P.74 states, “Travel time savings to public transport is estimated to be 4,033 hours per day across the whole network as a result of the light rail operation (in 2031).” The Business xv

Case did not explain how this estimate was derived. For the projected 5,195 AM peak and 5,012 PM peak patrons (p.65) that equates to 24 minutes of time saved per trip.

The following estimate indicates an average net time saving of 7.38 minutes per trip.

Walk to bus or tram stop: 1 minute loss (due to 1 km average spacing of 13 tram stops, compared with 0.63 km average spacing of 21 bus stops.)

Bus or tram travel time: 14 minute saving (tram travel time 19 minutes, allowing for some trips being less than the full distance; comparable bus AM peak travel time 42 minutes in 2031 based on current scheduled 27 minutes for the entire route at 2014 congestion levels, adjusted to 20 minutes to allow for some trips being less than the full distance, plus an additional 15 minutes of congestion delays – 22 minutes of additional congestion in the general traffic lanes, adjusted for some trips being less than the full distance and for the congestionavoiding affect of the existing transit lanes.)

Amenity benefit: 2 minute saving (“This amenity benefit is assumed to be valued at 10% of the journey time of the average light rail trip.” p.97.)

Bustram transfer time: 6 minute loss (12 to 28 minute cost per transfer: Currie, G, 2009, Research perspectives on the merits of Light Rail vs Bus, BITRE Colloquium Canberra 18

19 June 2009: http://www.infrastructureaustralia.gov.au/publications/files/LightRailVSBus.pdf Allow for late arrival: 3 minute saving. (One in four ACTION buses departs at least one minute early or arrives at least four minutes late. See http://www.action.act.gov.au/About_ACTION/howweretravellingpage/punctuality).

Walk from bus or tram stop to destination: 1 minute loss (due to 1 km average spacing of 13 tram stops, compared with 0.63 km average spacing of 21 bus stops.)

Net saving: 11minutes.

If 10,207 AM and PM peak patrons each save 11 minutes of travel time per trip, the total saving attributable to light rail is 1,871 hours per day.

Light rail will remove buses from the left lanes of Flemington Road and Northbourne Avenue (Table 4, p. 64) with an effect similar to adding new lanes for general traffic. Modelling results at p.51 show that light rail will AM peak reduce car travel times in 2031 by 15 minutes (i.e. from 57 minutes to 42 minutes).

“More than 5,000 car trips use the section between EPIC and the City” and “there are around 3,000 car trips using the stretch of road between Gungahlin and EPIC as part of a southbound journey to work that is fully within the corridor.” (p.52).

If GungahlinEPiC car trips increase in proportion to the population of Gungahlin grow in proportion to the population of Gungahlin (“Gungahlin’s population predicted to grow from its current population levels of around 50,000 to ... about 85,000 by 2031,” p.52), they will be 5,100 in 2031.

If EPiCCity car trips increase by the same number, they will be 7,100 in 2031.

Three minutes (38%) of current congestion delays are between Gungahlin and EPiC, and 4.8 minutes (62%) are between EPiC and the City (Table 9).

If the 15 minute travel time reduction due to light rail is split 38% (5.7 minutes) to GungahlinEPiC and 62% (9.3 minutes) to EPiCCity, then in 2031 those 12,200 drivers will save 1,585 hours each morning and a similar amount each afternoon, making a total of about 3,000 hours per day.

This compares with public transport travel time reduction estimates of 4,033 hours per day (Business Case) and 1,871 hours per day (as estimated in an endnote above).

xvi

xvii

“Increases in land values along the route may simply come at the expense of land values elsewhere in Canberra.” Former manager of major project analysis for ACT Treasury David Hughes, Canberra Times, October 14, 2014.

Boston Green Line totals 87 g GGE/PMT: Chester, Mikhail V. Lifecycle Environmental Inventory of Passenger Transportation in the United States. Institute of Transportation Studies, dissertations. 2008, Table 54 – Green Line Infrastructure Inventory.

© Copyright 2025