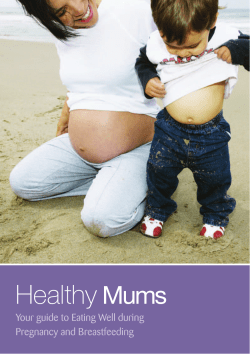

Maternal and pre-school child nutrition guidelines October 2012