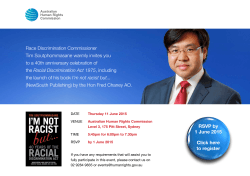

caste discrimination and human rights