Full Criminal Discovery in Kansas PDF fileâ¦

DISCOVERY IN KANSAS CRIMINAL CASES

1.

Summary.

A criminal defendant has significant mandatory and discretionary pretrial discovery

rights (a) under the Kansas Code of Criminal Procedure and (b) as recognized by the

Kansas appellate courts. A presumption in favor of full and open disclosure underpins

both mandatory and discretionary discovery. Other than protected Jencks materials,1 there

is no absolute bar on the compelled pretrial discovery of any category of materials for the

accused.

2.

Related Articles.

“The Use of Subpoenas in Kansas Criminal Cases to Obtain Discovery of

Documents, Records, Objects and Premises (And Anything Else) Controlled by Third

Persons.” A criminal defendant in Kansas has the right both by statute and under the

compulsory process clauses of the federal and state constitutions to obtain production

before trial of materials related to his defense by use of a subpoena duces tecum.

3.

Mandatory Discovery Is Governed by K.S.A. § 22-3212 (Supp. 2014) under the

Code of Criminal Procedure.

A.

The current criminal discovery statute.

The statutory authority for discovery in criminal actions is found in Kan. Sess. L. ch.

34, § 1 (2014), amending K.S.A. § 22-3212 (Supp. 2013). This discovery statute was first

enacted by the Kansas Legislature in 1970 as part of the new Kansas Code of Criminal Procedure. The statute now provides for mandatory production triggered by nothing more

than a defense “request” under subsections (a) and (b). Reciprocal discovery in favor of the

prosecution is established in subsection (c).

The current version of the statute, last amended in 2014, has three key parts. Section

(a) spells out the production duty of the prosecutor if a “request” is made with one

ambiguous condition – “if relevant.”

1

Jencks v. United States, 353 U.S. 657, 77 S.Ct. 1007 (1957), superceded by 18 U.S.C.A.

§ 3500(e) (added Pub. L. 85-269, Sept. 2, 1957, 71 Stat. 595; amended Pub. L. 91-452, Title I,

§ 102, Oct. 15, 1970, 84 Stat. 92.

(a) Upon request, the prosecuting attorney shall permit

the defense to inspect and copy or photograph the following,

if relevant:

(1) Written or recorded statements or confessions

made by the defendant, or copies thereof, which are or have

been in the possession, custody or control of the prosecution,

the existence of which is known, or by the exercise of due

diligence may become known, to the prosecuting attorney;

(2) results or reports of physical or mental examinations, and of scientific tests or experiments made in connection with the particular case, or copies thereof, the existence

of which is known, or by the exercise of due diligence may

become known, to the prosecuting attorney;

(3) recorded testimony of the defendant before a

grand jury or at an inquisition; and

(4) memoranda of any oral confession made by

the defendant and a list of the witnesses to such confession, the

existence of which is known, or by the exercise of due diligence

may become known to the prosecuting attorney.

It is hard to imagine a situation in which any of these four categories would not be

relevant. Further, one must assume that the “if relevant” condition to production in

subsection (a) has the same meaning given relevance in civil discovery. The material

sought itself need not be admissible at a trial; it is “relevant” for discovery if it might lead

to the discovery of evidence that is admissible at trial in support of a defense. See

Gleichenhaus v. Carlyle, 226 Kan. 167, 170, 597 P.2d 611 (1979) (“The scope of relevancy in

a discovery proceeding is broader than the scope of relevancy at trial. Relevancy includes

information which may be useful in preparation for trial. A request for discovery would

be considered relevant if there is any possibility that the information sought may be

relevant to the subject matter of the lawsuit.”).

Subsection (b) of the discovery statute is the second key provision. It now lists two

categories of discovery materials that are expressly defined as discoverable and then places

six limitations on the discovery related to those two categories:

-2-

(b)(1) Except as provided in subsection (l), upon request, the prosecuting attorney shall permit the defense to inspect and copy or photograph

books, papers, documents, tangible objects, buildings or places, or copies, or

portions thereof, which are or have been within the possession, custody or

control of the prosecution, and which are material to the case and will not

place an unreasonable burden upon the prosecution.

(2) The prosecuting attorney shall also provide a summary or

written report of what any expert witness intends to testify to on direct

examination, including the witness' qualifications and the witness' opinions,

at a reasonable time prior to trial by agreement of the parties or by order of

the court.

(3) Except as provided in subsections (a)(2) and (a)(4), and as

otherwise provided by law, this section does not authorize the discovery or

inspection of reports, memoranda or other internal government documents

made by officers in connection with the investigation or prosecution of the

case, or of statements made by state witnesses or prospective state witnesses,

other than the defendant.

(4) Except as provided in subsection (g), this section does not

require the prosecuting attorney to provide unredacted vehicle identification

numbers or personal identifiers of persons mentioned in such books, papers

or documents.

(5) As used in this subsection, personal identifiers include, but

are not limited to, birthdates, social security numbers, taxpayer identification

numbers, drivers license numbers, account numbers of active financial

accounts, home addresses and personal telephone numbers of any victims or

material witnesses.

(6) If the prosecuting attorney does provide the defendant's

counsel with unredacted vehicle identification numbers or personal identifiers, the defendant's counsel shall not further disclose the unredacted

numbers or identifiers to the defendant or any other person, directly or

indirectly, except as authorized by order of the court.

-3-

(7) If the prosecuting attorney provides books, papers or

documents to the defendant's counsel with vehicle identification numbers or

personal identifiers redacted by the prosecuting attorney, the prosecuting

attorney shall provide notice to the defendant's counsel that such books,

papers or documents had such numbers or identifiers redacted by the

prosecuting attorney.

(8) Any redaction of vehicle identification numbers or personal

identifiers by the prosecuting attorney shall be by alteration or truncation of

such numbers or identifiers and shall not be by removal.

The discovery statute also contains a provision for reciprocal discovery by the

prosecution, but it is only triggered in the defense first seeks discovery of scientific

evidence under subsection (a)(2), general discovery of physical evidence under subsection

(b)(1), or reports of expert witnesses under subsection (b)(2):

(c) If the defense seeks discovery and inspection under subsection

(a)(2) or subsection (b), the defense shall:

(1) Permit the attorney for the prosecution to inspect and copy

or photograph scientific or medical reports, books, papers, documents,

tangible objects, or copies or portions thereof, which the defense intends to

produce at any hearing, are material to the case and will not place an

unreasonable burden on the defense; and

(2) provide for the attorney for the prosecution a summary or

written report of what any expert witness intends to testify, including the

witness' qualifications and the witness' opinions, at a reasonable time prior

to trial by agreement of the parties or by order of the court.

To a large extent, subsection (c) mirrors what the prosecutor must provide the defense

under (b)(1) and (2). The statutory scope of mandatory discovery inn favor of the prosecution is more limited than the scope given the defense. There is no provision like (a)(2)

in favor of the prosecution and the defense only has to produce only those exhibits it

intends to “produce at any hearing.” More importantly, the defense can prevent a prosecutor’s discovery simply by not requesting discovery.

-4-

The rest of K.S.A. § 22-3212 covers very specific matters. For instance, subsection

(d) of the discovery statute is a reverse Jencks provision. If the defense cannot get reports

and witnesses’ statements from the prosecution, then the prosecution cannot get the reports

and witnesses’ statements from the defense:

(d) Except as to scientific or medical reports, subsection (c) does not

authorize the discovery or inspection of reports, memoranda or other

internal defense documents made by the defendant, or the defendant's

attorneys or agents in connection with the investigation or defense of the

case, or of statements made by the defendant, or by prosecution or defense

witnesses, or by prospective prosecution or defense witnesses, to the

defendant, the defendant's agents or attorneys.

The legislature made it very clear in subsection (f) that the trial court’s role in

criminal discovery is to be as limited as possible. Although the discovery statute speaks

only in terms of a request for discovery by the defense or prosecution, subsection (e) seems

to give the trial court some role in controlling at least the times and sequence of the disclosures if there is a disagreement. However, if the court is neither asked for nor gives an

order controlling times and sequence of the disclosures, either stipulations by the prosecution and defense or the statute itself controls timing and sequencing:

(e) All disclosures shall be made at the times and in the sequence

directed by the court. In the absence of other directions from the court or

stipulation by the parties, such disclosures shall be made as provided in this

section.

(f) The prosecuting attorney and the defense shall cooperate in

discovery and reach agreement on the time, place and manner of making the

discovery and inspection permitted, so as to avoid the necessity for court

intervention.

Subsection (g) of the discovery statute contains a truly remarkable procedure, which

has not yet been examined by any Kansas appellate court. The trial court is given the

power to deny, enlarge, or make any “other order as is appropriate” if either the prosecution or the defense simply makes a motion asking the trial court to examine an ex parte

statement justify something – the something does not need to be disclosed in the motion

requesting the ex parte examination of the written statement. In short, one of the litigants

will not even know what is going on behind closed doors.

-5-

(g) Upon a sufficient showing the court may at any time order that the

discovery or inspection be denied, restricted, enlarged or deferred or make

such other order as is appropriate. Upon motion, the court may permit either

party to make such showing, in whole or in part, in the form of a written

statement to be inspected privately by the court. If the court enters an order

granting relief following such a private showing, the entire text of the

statement shall be sealed and preserved in the records of the court to be

made available to the appellate court in the event of an appeal.

The statute makes no effort to define what “a sufficient showing” may be and it is hard to

imagine in light of the Jencks provisions what the prosecution or the defense might want

to hide. There are serious Brady and Giglio2 issues if the prosecution tries to hide or limit

the timing of disclosure of exculpatory evidence.

Although subsection (h) of the discovery statute requires that discovery is to be

completed no later than 21 days after the arraignment or such reasonable time as the court

may permit, most trial judges, prosecutors, and defense counsel pay little attention to this

time requirement or seek a scheduling order.3 The trial court also is given a good bit of

discretion on how to deal with discovery materials produced late.4

2

Brady v. Maryland, 373 U.S. 83 (1963); Giglio v. United States, 450 U.S. 150 (1972).

3

“(h) Discovery under this section must be completed no later than 21 days after

arraignment or at such reasonable later time as the court may permit.”

4

“(i) If, subsequent to compliance with an order issued pursuant to this section, and

prior to or during trial, a party discovers additional material previously requested or

ordered which is subject to discovery or inspection under this section, the party shall

promptly notify the other party or the party's attorney or the court of the existence of the

additional material. If at any time during the course of the proceedings it is brought to the

attention of the court that a party has failed to comply with this section or with an order

issued pursuant to this section, the court may order such party to permit the discovery or

inspection of materials not previously disclosed, grant a continuance, or prohibit the party

from introducing in evidence the material not disclosed, or it may enter such other order

as it deems just under the circumstances.”

-6-

To facilitate sentencing, the prosecution must provide the defendant’s adult and

juvenile criminal history.5

Lastly, following the lead of Congress, the Kansas Legislature has decided that

defense attorney’s and their experts cannot to be trusted with a “visual depiction of a child

under 18 years of age shown or heard engaging in sexually explicit conduct with intent to

arouse or satisfy the sexual desires or appeal to the prurient interest of the offender or any

other person.” The rationale advanced in Congress and followed by the Kansas Legislature

is so juvenile (pun intended) it does not deserve repeating or analysis. The limitation exists

- preparation of a defense is impeded and made more expensive - but the defense has to

live with it until the legislature realizes that the Board of Indigent Defense Services has to

pay a great deal more money to bring an expert from Chicago to look at visual depictions

than it would have to pay if the visual depictions were sent by Federal Express to the

expert in Chicago on an encrypted hard disk drive.6

5

“(j) For crimes committed on or after July 1, 1993, the prosecuting attorney shall

provide all prior convictions of the defendant known to the prosecuting attorney that

would affect the determination of the defendant's criminal history for purposes of

sentencing under a presumptive sentencing guidelines system as provided in K.S.A.

21-4701 et seq., prior to their repeal, or the revised Kansas sentencing guidelines act, article

68 of chapter 21 of the Kansas Statutes Annotated, and amendments thereto.

“(k) The prosecuting attorney and defense shall be permitted to inspect and copy

any juvenile files and records of the defendant for the purpose of discovering and verifying

the criminal history of the defendant.”

6

“(l)(1) In any criminal proceeding, any property or material that constitutes a

visual depiction, as defined in subsection (a)(2) of K.S.A. 21-5510, and amendments thereto,

shall remain in the care, custody and control of either the prosecution, law enforcement or

the court.

“(2) Notwithstanding subsection (b), if the state makes property or material

described in this subsection reasonably available to the defense, the court shall deny any

request by the defense to copy, photograph, duplicate or otherwise reproduce any such

property or material submitted as evidence.

“(3) For the purpose of this subsection, property or material described in this

(continued...)

-7-

B.

There have been very few significant amendments to the discovery statute

since 1970.

There have been a number substantive amendments of the discovery statute since

its original enactment in 1970. Kan. Sess. L. ch. 129, § 22-3212 (1970).

When the statute was first enacted, it required the involvement of the court to a very

large degree. That was all changed in 1980 by the Kansas Supreme Court. 228 Kan. clvi

(Dec. 5, 1980). The two key discovery subsections of the first statute began with this clause:

“Upon motion of a defendant the court may order the prosecuting attorney to permit . . .

.” This clause was changed by the Kansas Supreme Court in 1980 to read: “Upon request,

the prosecuting attorney shall permit . . . .”

The 1970 version also required that a discovery motion had to be made not later than

20 days after the arraignment and had to include all the items of discovery sought. A later

motion or an expanded motion could only be made as permitted by the court and in the

interest of justice. The 1980 amendment simply provided that requested discovery had to

be completed not later than 20 days after the arraignment.

The first version also required the discovery order to spell out the “time, place and

manner of making the discovery and inspection.” That was deleted in 1980 and replaced

with the direction that the prosecuting attorney and defendant are to cooperate in discovery “to avoid the necessity for court intervention.”

Court involvement since the 1980 amendment does not occur, under the terms of the

statute, unless a motion to compel or for sanctions is made under what is now subsection

(i). 288 Kan. clvii (Dec. 5, 1980) (formerly subsection 7). A judge may become involved

earlier, however, if a motion for discovery of something not specified in the statute is made

by the prosecution or the defense.

6

(...continued)

subsection shall be deemed to be reasonably available to the defense if the prosecution

provides ample and liberal opportunity for inspection, viewing and examination of such

property or material at a government facility, whether inside or outside the state of Kansas,

by the defendant, the defendant's attorney and any individual the defendant may seek to

qualify to furnish expert testimony at trial.”

-8-

In 1992, as part of the adoption of the Kansas sentencing guidelines scheme, the

legislature made one substantive change. Subsection (h) was added to require the prosecution to furnish the defense with the adult criminal history of the defendant that would

impact the defendant’s criminal history category. Kan. Sess. L. ch. 239, § 259 (1992).

In 1994, a new sections (k) was added to require the prosecution to furnish the

defense with the juvenile offender history of the defendant that would impact the

defendant’s criminal history category. Kan. Sess. L. ch. 291, § 61 (1994).

In 1997, subsection (c) was amended to broaden the obligation for reciprocal production by the defense. Prior to this amendment, the prosecution was obligated following

subsection (a)(2) and (b) requests to produce for the defense test reports and a number of

items that were material to the case. However, the defense’s reciprocal obligation was

limited to producing only the list of items “the defendant intends to produce at trial.” Kan.

Sess. L. ch. 181, § 4 (1997). There was no obligation to produce those items if they were

intended for introduction only at a pretrial hearing. The 1997 amendment deleted the

reference to “the trial” and inserted the phrase “any hearing.” The prosecution’s and the

defense’s discovery obligations are not yet co-extensive, but the 1997 amendment moved

them closer together.

And, lastly, in 2012, the Kansas Legislature decided that defense attorney’s are

allowed to arouse their sexual desire by looking at visual depictions of children engaged

in sexual acts only in the prosecutor’s office, but the prosecutor is able to do so anytime or

place he wishes. Kan. Sess. L. ch. 143, § 1 (2013).

In 2014, the legislature added the provision requiring the prosecution to provide the

defendant “a summary or written report of what any expert witness intends to testify to

on direct examination, including the witness' qualifications and the witness' opinions, at

a reasonable time prior to trial by agreement of the parties or by order of the court.” Kan.

Sess. L. ch. 34, § 1 (2014). That subsection previously mandated the disclosure not less than

30 days before the trial. Kan. Sess. L. ch. 133, § 12 (2013).

C.

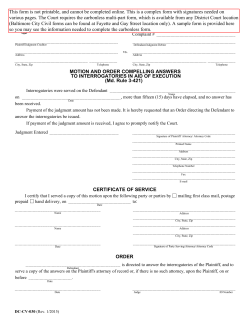

Discovery request forms.

To invoke a defendant’s discovery rights under subsections (a) and (b), only a

“request” is necessary. Despite the defense bar’s persist use of discovery motions filed

under the statute, a motion and order have not been required for more than 25 years. The

distinction between a request and an order is found in the statute itself as well as in its

-9-

history. Subsection (g) governs what happens when there is a discovery failure. It sets out

the steps to be taken when “a party discovers additional material previously requested or

ordered which is subject to discovery or inspection under this section.” Even though a

request is all that is needed, it is still a common practice among Kansas defense counsel to

move for an order of discovery. In the interests of judicial economy, as recognized by the

Supreme Court’s 1980 amendment of the statute, the preferred practice is for defense

counsel to submit a written request to the prosecutor and to file the original request with

the court clerk.

This is a simple request form that can be served and filed:

Defendant’s First Request for

Statutory Discovery and Inspection

The defendant requests the prosecuting attorney to permit the

defendant to inspect and copy or photograph all the materials for which

discovery is mandated by Kan. Sess Laws, ch. 34, § 1 (2014), amending K.S.A.

22-3212 (a), (b), (j), (k), and (l) (2013).

It is a good practice to title the initial document the “first request.” Subsequent discovery

requests for specific items falling within one of the statutory subsections can be given a

number in the title that distinguishes it from other requests.

While the short form is a sufficient request under K.S.A. § 22-3212, a detailed request

may be helpful for part-time prosecutor’s offices with small caseloads. The long request

form merely repeats the language of the statute in separate paragraphs. It is a convenient

checklist for a prosecutor’s secretary. This is the long request form:

Defendant’s First Request for

Statutory Discovery and Inspection

The defendant requests the prosecuting attorney to permit the defendant to

inspect and copy or photograph the following:

1. Written or recorded statements or confessions made by the

defendant that are or have been in the possession, custody, or control of the

prosecution, the existence of which is known, or by the exercise of due

diligence may become known, to the prosecuting attorney.

-10-

2. Results or reports of physical examinations, and of scientific tests

or experiments made in connection with the particular case, the existence of

which is known, or by the exercise of due diligence may become known, to

the prosecuting attorney.

3. Recorded testimony of the defendant before a grand jury or at an

inquisition.

4. Memoranda of any oral confession made by the defendant and a list

of the witnesses to such confession, the existence of which is known, or by

the exercise of due diligence may become known to the prosecuting attorney.

5. Books, papers, documents, tangible objects, buildings or places, or

copies, or portions thereof, that are or have been within the possession,

custody or control of the prosecution, and that are material to the case and

will not place an unreasonable burden upon the prosecution.

6. All prior convictions of the defendant known to the prosecuting

attorney that would affect the determination of the defendant's criminal

history for purposes of sentencing under the presumptive sentencing

guidelines system.

7. All juvenile files and records of the defendant known to the

prosecuting attorney for the purpose of discovering and verifying the

criminal history of the defendant.

Rather than automatically issuing a blanket request for statutory discovery in every

case, consider your case carefully and think about limiting the request. For instance, if

expert or other scientific or medical evidence is going to play an important part in the

defense, it may be tactically advisable NOT to request discovery under subsection (a)(2)

until a later time. Frequently prosecutors overlook the absence of a subsection (a)(2) request

and produce all expert witness materials. Be thankful because then you have no reciprocal

discovery obligation.

-11-

4.

Discovery May Be Ordered by the Court for Anything Relevant to the Defense.

A.

The list of mandatory discovery items in K.S.A. § 22-3212 is not exclusive.

K.S.A. § 22-3212 must not be read to limit discovery to the specifically listed

materials. The court can order production of anything under the State’s control as long as

production is not expressly barred by statute.

This is not a change from the practice before the 1970 enactment of the Kansas Code

of Criminal Procedure. Discovery orders have long been discretionary in Kansas. Perhaps

the last case to recognize this pre-Code standard was State v. Martin, 206 Kan. 388, 480 P.2d

50 (1971). Martin was charged with murder. He moved for the pretrial production and

inspection of a knife and some clothing in the possession of the prosecution. The motion

was denied. On appeal, the supreme court noted: "Other than the bald assertion of prejudice, defendant has failed to demonstrate in what manner his substantial rights were

affected by the denial of his motion." The denial of the discovery motion was affirmed. The

supreme court in this pre-Code case acknowledged without any discussion that discretion

to order discovery is vested in the district court:

Ordinarily, an application by the accused to inspect articles in the state's

possession which are relevant to the charge is addressed to the discretion of

the court, whose ruling will be set aside only upon a showing of an abuse of

discretion.

206 Kan. at 390.

Decisions under K.S.A. § 22-3212 have described the district court’s discovery

discretion in the broadest terms. The clearest example of this is State v. McIntosh, 274 Kan.

939, 58 P.3d 716 (2002), in which the supreme court found error in the district court’s

refusal to order a physical examination of a complaining witness, something not mentioned

at all in K.S.A. § 22-3212.

McIntosh was convicted of aggravated criminal sodomy, rape, and aggravated

indecent liberties with a child occurring over three years. Prior to trial, McIntosh filed a

motion requesting a physical examination of the alleged victim. The trial court denied the

motion. The court of appeals affirmed the denial of McIntosh’s motion. In so doing, the

court of appeals held that only those items expressly listed in section 22-3212 are subject

-12-

to discovery. Since a physical examination is not listed in the statute, the court held that the

trial court had no authority to order such an examination.

The supreme court granted McIntosh’s petition for review and reversed the court

of appeals, ruling that the trial court erred in denying McIntosh’s motion. The supreme

court expressly rejected the court of appeal’s reasoning:

This reasoning assumes that K.S.A. 2001 Supp. 22-3212 sets forth every

possible item subject to discovery in a criminal case. The Court of Appeals

failed to note that this court specifically recognized the contrary in State v.

Davis, 266 Kan. 638, Syl. ¶ 1, 972 P.2d 1099 (1999). The Davis court was faced

with determining whether the district court had the authority to order the

county attorney to mail documents to the defense that were clearly subject

to discovery and under the control of the State. K.S.A. 2001 Supp. 22-3212

provides that the prosecutor must permit the defense to "inspect and copy,

or photograph" the documents, but does not specifically provide that the

county attorney must mail the documents. The Davis court held that the

district court had the discretionary authority to order the county attorney to

mail the documents.

In reaching its decision, the Davis court observed:

"K.S.A. 22-3212 is based on Fed. R. Crim. Proc. 16. See State v. Jones, 209

Kan. 526, 528, 498 P.2d 65 (1972). The Federal Advisory Committee, in its

notes on Rule 16, states:

'[Rule 16] is intended to prescribe the minimum amount of discovery to

which the parties are entitled. It is not intended to limit the judge's discretion

to order broader discovery in appropriate cases. For example, subdivision

(a)(3) is not intended to deny a judge's discretion to order disclosure of grand

jury minutes where circumstances make it appropriate to do so.' Federal

Advisory Committee's Notes on 1974 Amendment on Rule 16.

"Federal courts interpreting Rule 16 have held that it is within the

sound discretion of the district judge to make any discovery order that is not

barred by higher authority. See United States v. Campagnuolo, 592 F.2d 852, 857

n. 2 (5th Cir. 1979); United States v. Sawyer, 831 F.Supp. 755, 757 (D. Neb.

1993)." Davis, 266 Kan. at 642-43, 972 P.2d 1099.

-13-

See also United States v. Richter, 488 F.2d 170, 173 (1973) ("The Federal

Rules of Criminal Procedure are intended to constitute a comprehensive

procedural code for criminal cases in the federal courts. But even the rules

themselves do not purport to set outer limits of the power of the court.").

The text of K.S.A.2001 Supp. 22-3212 is not all-inclusive. The fact

submission to physical examinations is not specifically provided for under the statute

does not mean the district court does not have the authority to order the examination

in a particular case. Therefore, the Court of Appeals erred in relying upon

K.S.A. 2001 Supp. 22-3212 to divest the district court of the authority to order

a physical examination.

274 Kan. at 949-50 (emphasis added).7

B.

Judicial and legislative policy favors full disclosure.

Five years after the 1970 enactment of K.S.A. § 22-3212, the Kansas Supreme Court

announced the fundamental policy principles to guide the district courts in criminal

discovery. The case was State v. Humphrey, 217 Kan. 352, 537 P.2d 155 (1975).

Humphrey was charged with multiple counts of illegal drug sales. “With the

exception of the testimony of a Kansas Bureau of Investigation chemist who identified the

drugs, the prosecution was based solely upon the testimony of John Eckhart, a special

agent of the Kansas Attorney General.” 217 Kan. at 353. Eckhart told the jury that he

7

Consist with its earlier decision in State v. Gregg, 226 Kan. 481, 602 P.2d 85 (1979),

concerning the district court’s authority to order a psychological examination of a

complaining witnesses in a sex offense case, the McIntosh court also held:

A district judge has the discretion to order a psychological or physical

examination of the victim in a sex crime case if the defendant presents a

compelling reason for such examination. Even if a district court finds a

compelling reason for ordering the psychological or physical examination,

further safeguard as to its admissibility remains.

266 Kan. at 939, Syl. ¶ 2.

-14-

bought marijuana and amphetamines from Humphrey on two separate occasions.

Humphrey’s defense was based on attacking Eckhart’s credibility during crossexamination and by presenting the testimony of Eckhart’s former wife and three

acquaintances.

Humphrey’s lawyer requested the district court to compel the prosecutor to produce

Eckhart’s criminal history record. The court denied the request. On appeal, the supreme

court held that the district court erred. The discovery statute was different in 1975. The

essence of what is now subsection (b) was then subsection (2). It provided for discovery on

motion by the defense and after certain hurdles were cleared by the defense. As the

Humphrey court wrote:

Such information would be discoverable if it is included within the ambit of

K.S.A. 22-3212 (2) which provides as follows:

"22-3212. Discovery and inspection.

...

"(2) Upon motion of a defendant the court may order the prosecuting

attorney to permit the defendant to inspect and copy or photograph books,

papers, documents, tangible objects, buildings or places, or copies, or

portions thereof, which are or have been within the possession, custody or

control of the prosecution upon a showing of materiality to the case and that

the request is reasonable. . . ."

It should be noted that this statute places in the trial court a broad

discretion to require the prosecuting attorney to disclose to the defendant

documents and other tangible objects which are or have been within the

possession or control of the prosecution. In order to obtain such discovery

the defendant has the burden of showing the materiality of the information

and that the request is reasonable.

217 Kan. at 357-58. The Humphrey court had no difficulty concluding that “absent some

good reason” a prosecutor should disclose a witness’ criminal history for crimes involving

dishonesty or false statement. The supreme court was careful to recognize that the district

court has broad discretion under K.S.A. § 22-3212 andthere must be a reason to deny

discovery:

-15-

We are simply declaring that under 22-3212 the trial court should liberally

grant discovery on motion of a defendant unless there is some good sound

reason to deny discovery. The norm should be for the trial court to allow discovery

to the defendant. An arbitrary refusal without reason to require the prosecutor

to disclose material information constitutes an abuse of discretion for the

reason that such action is contrary to the purpose of the Kansas Code of

Criminal Procedure and the minimum standards for criminal justice

discussed above.

217 Kan. at 359-60 (emphasis added).

The Humphrey court also considered the scope of K.S.A. § 22-3213, which controls

the disclosure of the witnesses’ statements. After Eckhart testified at the preliminary

hearing, Humphrey’s lawyer requested the production of Eckhart’s statements. The district

court ordered the production of Eckhart’s statements in the county attorney’s file but

denied the request for production of Eckhart’s statements held by the Attorney General’s

office. In ruling that the district court’s decision was wrong, the supreme court plainly set

the standard for enforcement of the discovery statute in the Code of Criminal Procedure:

The Kansas Code of Criminal Procedure by the provisions of 22-2103

declares that it is intended to provide for the just determination of every

criminal proceeding. Its provisions shall be construed to secure simplicity in

procedure, fairness in administration and the elimination of unjustifiable

expense and delay. In view of these stated purposes it is clear that the discovery

provisions under the criminal code should be liberally construed and the scope of

discovery should be as full and complete as is reasonably possible under the

circumstances.

217 Kan. at 356 (emphasis added).

For more than 30 years, the principles announced in Humphrey have remained the

law of Kansas. See e.g., State v. Burnison, 247 Kan. 19, 25, 795 P.2d 32 (1990), and State v.

Brinkley, 256 Kan. 808, 819, 888 P.2d 819 (Kan. 1995) (citing Humphrey) and State v. Kessler,

276 Kan. 206, ¶ 6, 73 P.3d 761 (2003) (citing Brinkley), repeating the rule that discovery in

criminal cases is to “be as full and complete as is reasonably possible under the circumstances.” In In re S.D.S., 2005 WL 43416 (Kan. App. 2005) (unpublished), the court of

appeals citing Kessler described the rule favoring discovery in criminal cases as unequivocal:

-16-

S.D.S. claims his request for exculpatory discovery material was

denied by the court. Our rules on such matters are unequivocal. Discovery

in criminal cases favors disclosure as fully and completely as is reasonably

possible. State v. Kessler, 276 Kan. 202, 212, 73 P.3d 761 (2003); See K.S.A.2003

Supp. 22-3212. The district court has broad discretion to require the

disclosure of relevant material that is in the possession of or under the

control of the State. 276 Kan. at 212.

C.

Even though policy favors full and complete discovery, the defense still

needs to make some showing of materiality and reasonableness to support

a discovery motion.

Criminal discovery is not unlimited despite the policy favoring full and complete

disclosure. In moving for a discovery order for some specific item, an accused still must

make a threshold showing that the item is material to the case and the request is

reasonable. The defendant in State v. Dykes, 252 Kan. 556, 847 P.2d 1214 (1993), was charged

with kidnapping and rape. Semen was found on the victim’s slacks. It was analyzed by the

FBI laboratory. Dyke’s DNA was consistent with the profile obtained from the semen

specimen. An FBI agent testified that the “probability of selecting another unrelated

individual chosen at random from the black population having a profile similar to Dykes’

is approximately one in six million.” Prior to trial, Dykes files a lengthy discovery motion

concerning the FBI’s database:

Dykes' motion to discover the FBI data base is a 12-page blanket

request for every conceivable document generated by the FBI and others

relating to any and all DNA testing, the calculation of probabilities of

population, genetic population, *559 and all information and tests used to

compute the DNA data base. In part, the motion requests:

(1) A written copy of a hard or soft copy of any computer program

describing the FBI's method for calculating frequencies of individual alleles

and calculating combined frequencies of the various probes used.

(2) For each probe used in this case, the test relied upon for

determining whether the population is in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium,

including the tables reflecting the raw phenotypic and genotypic data for the

black population.

-17-

(3) The source of samples for the black population data base including

the type, profession, or geographical region of people selected and the

criteria for determining the samples came from blacks.

The motion also requested any information accompanying samples

which pertains to the racial origin of the samples subject to proficiency

testing, the names of all analysts who performed the test on the samples, and

their notes, training, and results of the test.

252 Kan. at 558-59. The district court denied this motion.

On appeal, Dykes claimed the denial of his discovery motion was error. The

supreme court disagreed. Citing State v. Campbell, 217 Kan. 756, 782, 539 P.2d 329, cert.

denied, 423 U.S. 1017, 96 S.Ct. 453, 46 L.Ed.2d 389 (1975), this was the test applied by the

court to determine whether the district court abused its discretion:

For evidence to be discoverable, the defendant must show that the

evidence requested is in the possession or control of the prosecution and that

it is relevant or material in the preparation of the defense. The mere entertaining of a hope that something of aid may be discovered is not sufficient.

The court stated this test in two separate syllabi at the start of the opinion:

1. K.S.A. 22-3212 allows the trial court broad discretion to require

disclosure of documents and other tangible objects which may be in the

possession of or under the control of the prosecution. The defendant has the

burden of showing the materiality and reasonableness of a discovery request.

2. K.S.A. 22-3212 requires that the information sought by a criminal

defendant must be material to the particular case and capable of acquisition

by the prosecution with the exercise of due diligence, and the production of

the information must not place an unreasonable burden on the prosecution.

5.

Conclusion.

Criminal discovery from the prosecution in Kansas is remarkably broad. The only

limitations are the state Jencks act concerning witness statements, K.S.A. § 22-3213 (Supp.

2005), relevance, and reasonableness. A written request is all that is needed to secure

-18-

discovery of the items listed in K.S.A. § 22-3212(a) and (b). A motion with a showing of

relevance and reasonableness will secure production of anything else held by the

prosecution.8

8

And, do not forgot, discovery of tangible evidence and inspection of physical

places can be obtained pre-trial from third-parties using a subpoena. “The Use of

Subpoenas in Kansas Criminal Cases to Obtain Discovery of Documents, Records, Objects

and Premises (And Anything Else) Controlled by Third Persons.”

-19-

© Copyright 2025