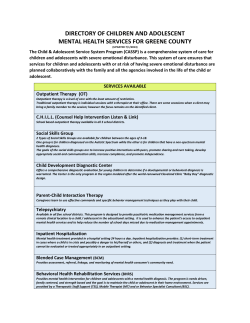

ADVOCATING FOR CHILDREN AND YOUTH IN RESIDENTIAL