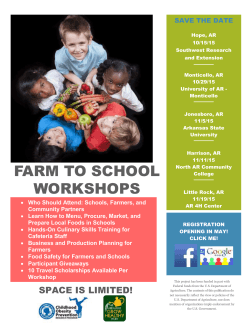

fulltext