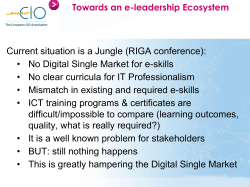

- European Conference on Digital and key enabling