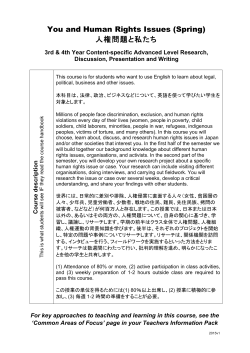

The Barefoot Guide 4