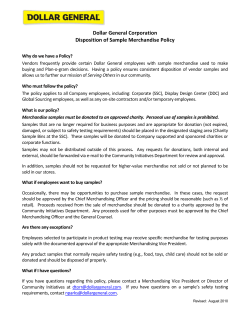

Merchandise Management