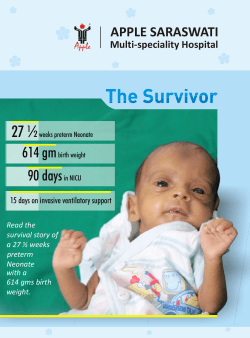

The pregnancy and post birth experience