Dianne B Cherry 1980; 60:877-881. PHYS THER.

Review of Physical Therapy Alternatives for

Reducing Muscle Contracture

Dianne B Cherry

PHYS THER. 1980; 60:877-881.

The online version of this article, along with updated information and

services, can be found online at:

http://ptjournal.apta.org/content/60/7/877

Collections

This article, along with others on similar topics, appears

in the following collection(s):

Manual Therapy

Spasticity

e-Letters

To submit an e-Letter on this article, click here or click on

"Submit a response" in the right-hand menu under

"Responses" in the online version of this article.

E-mail alerts

Sign up here to receive free e-mail alerts

Downloaded from http://ptjournal.apta.org/ by guest on September 9, 2014

Review of Physical Therapy Alternatives for

Reducing Muscle Contracture

DIANNE B. CHERRY, MS

Passive stretching is a technique frequently used to treat muscle contractures;

however, because it can activate the stretch reflex and has little carry-over, it

may not be as effective as other modes. Four approaches to treating muscle

contracture are described: 1) activation or strengthening of the weak opponent,

2) local inhibition of the contracted muscle, 3) general inhibition of hypertonus,

and 4) passive lengthening. Specific examples of techniques, their rationales,

and suggestions for use of each are discussed.

Key Words: Contracture, Exercise therapy, Muscles, Physical therapy.

A primary objective of physical therapy is maintaining or regaining range of motion in cases of

orthopedic or neuromuscular dysfunction, in order to

prevent or reduce myostatic contracture. A muscle

may become tight and develop a myostatic contracture if the joint it crosses does not go through full

range of motion regularly. Manual passive stretching

of the tight structures is frequently used to prevent or

reduce such contractures.1-4 Passive stretching is the

most obvious and direct solution; unfortunately,

stretching may be of limited effectiveness and is often

painful.4 Research in kinesiology and neurophysiology provides some alternatives to passive stretching.

These alternatives will be reviewed, and the purposes

and rationale of each will be considered.

There are many possible causes of myostatic contracture, which can be understood as an intrinsic

muscle shortening sufficient to prevent full range of

motion, though at the end of the available range there

is a resiliency or spring. The problems of limited

range of motion caused by capsulitis, bony deformity,

skin or soft tissue contracture, or fixed irreversible

muscle contracture of long-standing duration are best

treated by modalities and methods other than those

to be discussed here. Individual muscles will not be

discussed, since contracture can present a problem in

almost any muscle. For clarity, the tight or contracted

muscle will always be referred to as the antagonist,

for it opposes the motion desired, while its opponent

Ms. Cherry is Assistant Professor of Physical Therapy, Department of Health Science, Cleveland State University, Cleveland, OH

44115 (USA).

This article was submitted September 19, 1978, and accepted December 18, 1979.

on the other side of the joint will be referred to as the

agonist, whose movement would be in the direction

desired to reduce the contracture.

CAUSES OF CONTRACTURE

Most definitions of muscle contracture include the

concept that a muscle or group of muscles has

shortened sufficiently to prevent complete range of

motion of the joint or joints it crosses.2-4 The shortening may be caused by intrinsic adaptive change in

response to prolonged positioning, as often occurs

after orthopedic immobilization.2 Another cause is

poor positioning, as in poliomyelitis or myelomeningocele with dynamic imbalance of muscle power,

when a stronger, unopposed muscle shortens and is

never lengthened by its weak opponent.1, 5 Contracture may also result from influences extrinsic to the

muscle; for instance, CNS damage can cause spasticity and prolonged fixed postures.2 The result may be

the same as in intrinsically caused contracture, with

the spasticity "accompanied by reciprocal inhibition

and weakness in the antagonist muscle group, giving

rise to unbalanced muscle pull and the development

of contractures."6 (Wyke's use of the term antagonist

is opposite to the meaning used in this article.)

ALTERNATIVE APPROACHES TO REDUCING

MUSCLE CONTRACTURE

Passive stretching uses forced motion to restore the

normal range of motion when this range is limited by

loss of soft tissue elasticity.3 Its effect on muscles is to

lengthen the elastic portion of the muscle passively,

allowing greater length and hence greater range at

Volume 60 / Number 7, July 1980

Downloaded from http://ptjournal.apta.org/ by guest on September 9, 2014

877

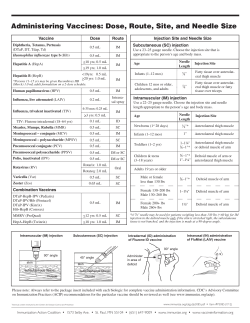

I. Activation or Strengthening of the Weak Agonist

A. Resistance or load

1. maximal resistance in diagonal spiral patterns

2. progressive resistance exercises

B. Unconscious automatic righting and equilibrium

reactions

C. Facilitatory techniques

1. vibration to agonist

2. quick icing and brushing

3. tapping

4. EMG feedback

5. manual contacts

6. traction

7. approximation

8. repeated contractions

9. quick stretch

II. Local Inhibition

A. Vibration to agonist

Figure. Summary of suggested

III. General Inhibition

A. Key points of control

B. Slow rocking

C. Slow rhythmical rotation of pelvis

on thorax

D. Moving surface

E. Inverted position

IV. Passive Lengthening

A. Prolonged positioning

1. orthoses and splints

2. adaptive equipment

3. positioning for activities of daily

living

B. Manual passive stretch

techniques for reducing muscle

the affected joints. However, "any increase in range

obtained by forced motion will be lost unless maintained by active motion or by supportive devices."3

Passive motion requires no participation by the patient and results in no motor learning, so it does not

improve the capacity for active motion of the tight

muscle or its opponent. Muscle tightness is therefore

likely to recur. Also, inasmuch as passive lengthening

stimulates the stretch reflex,7, 8 which causes the muscle to contract even more, passive stretching becomes

a self-defeating activity. Thus, passive stretch may

not be the technique of choice in treating muscle

tightness. Alternative solutions for lengthening contracted muscles should be explored.

Physiology and technique must be considered in

selecting the most appropriate method to reduce contracture (Figure). Integrity of the muscle and surrounding muscles and their innervation are important

considerations. When tightness is caused by spasticity,

the spastic muscle responds to stretch differently than

does normal muscle. The spastic muscle or muscle

group is characterized by exaggerated resistance to

passive stretch and, frequently, powerful reciprocal

inhibition of its opponent.9 Tightness caused by spasticity and tightness of a normal muscle adaptively

shortened because of plaster immobilization may require different modes of intervention. Treatment is

more effective in preventing contractures from spasticity than it is in reducing it. The ability of the

patient to cooperate and participate in treatment is

another factor to be considered in selecting a method

of treatment.

Four approaches to lengthening or stretching reversible muscle contractures will be discussed. One

approach is to activate or strengthen the weak, over-

878

B. Neutral warmth

C. Prolonged icing

D. Hold-relax/contract-relax

contracture.

stretched agonist opposing the tight muscle. A second

approach is to inhibit selectively the tight muscle so

it will tolerate being stretched without immediate

activation of the stretch reflex. A third approach is to

reduce hypertonus, when present, in the limb or the

entire body to allow a spastic tight muscle group to

relax and be lengthened. The last approach is passive

lengthening. Some of these methods may be used

simultaneously—one may enhance another. Many of

the techniques proposed have been found to be empirically effective but must be validated by clinical

research.

Activating or Strengthening the Weak Agonist

The agonist working in opposition to a contracted

muscle is in a position of excess length, to which it

has adapted by changing its spindle bias.8, 10 The

agonist is unable to shorten effectively against the

contracture in its antagonist. If innervation is intact

and the agonist has the ability to function at all, a

double benefit will be gained by improving its ability

to contract. If the agonist becomes stronger, it will be

able to counter the contracture of the antagonist and

pull the joint through more complete range. Also, the

antagonist will be reciprocally inhibited,10 allowing

itself to be stretched because the stretch reflex is also

inhibited. Ultimately, if the weak agonist can be

activated and strengthened, better muscle balance

around the joint may result, reducing the potential

for recurrence of myostatic contracture.4, 7

Strengthening the muscle opposing a contracted

muscle is an approach that may be applied to almost

any kind of patient in whom the agonist can be

activated. Techniques that improve or facilitate the

PHYSICAL THERAPY

Downloaded from http://ptjournal.apta.org/ by guest on September 9, 2014

function of the weak agonist are very useful for the agonist fail. Also, even if the agonist can be

orthopedic rehabilitation as well as for treating neu- activated, it will move through more complete range

rological problems because if innervation is intact, of motion if the stretch reflex of the tight antagonist

muscles are likely to respond to treatment most opti- can be inhibited; therefore, inhibition of the tight

mally. Examples of clinical problems in which acti- muscle should be considered. Inhibition can be devation of the weak agonist may be effective are muscle veloped locally within a limb segment or it can be

contracture in the remainder of an amputated limb, obtained more generally within the limb and entire

after immobilization for a fracture or other reasons, body by way of the CNS.

lower motor neuron lesions in which some intact

Local inhibition is useful for localized tightness,

innervation remains, and spasticity and hypertonus.

especially within one muscle group at one joint, such

Selection of technique will depend on the nature of as after plaster immobilization following injury or

the problem and the ability of the patient to cooper- surgery. Vibration to the opposing muscle group

ate. Effective strengthening methods that employ re- causes reciprocal inhibition to the contracted mussistance or load on the muscle include maximal re- cle.10, 15 Neutral warmth causes decreased gamma mosistance in diagonal spiral patterns11 and progressive tor neuron activity; prolonged icing causes slower

resistance exercises.12 Methods that use unconscious nerve conduction and diminished spindle and myautomatic responses to activate the weak agonist in- otatic reflex activity.19 The hold-relax and contractclude elicitation of the righting and equilibrium re- relax techniques of proprioceptive neuromuscular faactions.10, 13, 14 The long-term effectiveness of these cilitation11 work by means of successive induction,

techniques results from demanding that muscles prac- when a muscle is inhibited after a contraction while

tice skills that they will be expected to perform when its opponent is facilitated.10 The hold-relax procedure

has been found to be more effective than passive

therapy is completed.

If the agonist is extremely weak or inhibited or stretching in lengthening the hamstring muscles in

both, facilitatory techniques may enhance its function normal individuals.20

and increase its strength, thereby enabling it to oppose

the tight antagonist effectively. These facilitation

techniques use exteroceptive and proprioceptive stimGeneral Inhibition

ulation, causing summation in the CNS, which lowers

the threshold of efferent, or muscle action, response.

Carefully applied stimulation may make it easier for

Another approach to passive stretching is based on

the desired muscle to respond.10 Many different kinds inhibition of muscle tone throughout the body, which

of techniques facilitate the function of a weak muscle. may be accomplished through both somatic and auFor example, vibration,10, 15 quick icing and brush- tonomic components of the CNS. Generalized inhiing,7, 16 and tapping14 may be done easily with simple bition may be particularly effective when hypertonus

equipment. Electromyographic (EMG) feedback has or spasticity interferes with normal movement. Inhibeen effective in improving control in muscles oppos- bition causing a reduction of hypertonus may allow

ing spasticity.17 Proprioceptive neuromuscular facili- greater active or passive range of motion because the

tation includes a variety of techniques such as manual stretch reflex would not respond as readily to movecontacts, traction, approximation,18 repeated contrac- ment. Spasticity can be considered a release-fromtions, quick stretch, and resistance.11 All of these inhibition phenomenon. Therefore, methods that detechniques, used individually or in combination, en- velop inhibition may decrease spasticity and improve

able a therapist to elicit a response from a weak or motor control.6 Inhibitory techniques may also be

inhibited muscle that the patient alone is unable to effective when a patient's neuromuscular control is

activate adequately.

inadequate (because of age, mental status, or CNS

Vibration may be particularly useful when the an- dysfunction) to participate in the activation of the

tagonist is spastic and the agonist is very much in- agonist or the hold-relax technique. Bobath9, 21 and

hibited. Applying vibration to the weak agonist can Rood16 have both developed techniques that use genhelp cause activation in that muscle and simultaneous eralized inhibition of hypertonus. Bobath has dereciprocal inhibition in its spastic antagonist, allowing scribed particular movement patterns of proximal

easier movement in the desired direction.15

joints ("key points of control") that affect tone of the

trunk and limbs.14, 21 By these patterns of movement

Local Inhibition

the tight or spastic muscle groups may be inhibited

and, simultaneously, normal movement facilitated.

An agonist may be unable to contract at all, or a This technique enables the patient to develop active

muscle may be so tight that attempts to strengthen agonist control at the same time, enhancing effective-

Volume 60 / Number 7, July 1980

Downloaded from http://ptjournal.apta.org/ by guest on September 9, 2014

879

ness of the treatment. When the spastic limb is inhibited, its muscles will not respond to stretch as

readily, permitting the limb to move through more

complete range of active motion and preventing the

development of myostatic contractures.

Ayres has proposed that slow rocking, which provides vestibular stimulation of low frequency, inhibits

the reticular formation of the CNS and has a calming

effect.22 It is a technique employed by parents of

infants over the ages and is probably the basis for

such calming measures as using wind-up swinging

chairs and walking the floor. For the individual with

spasticity, slow rocking may help reduce tone to allow

normal movement.

Little has been written about several other inhibitory techniques, learned empirically by those therapists working with very spastic patients. One such

technique is slow, rhythmical rotation about the body

axis, frequently the pelvis rotating on the thorax. It

may be done manually by the therapist, and certain

spastic individuals may learn to rotate themselves.

This slow rotation reduces hypertonus in the limbs

and trunk, allowing more freedom of movement and

more normal movement. The rationale for this technique has not been described but may be related to

Bobath's "key points of control"14, 21 and elicitation

of normal righting reactions.13

Another little-described or -explained technique

that may empirically be found effective in decreasing

spasticity is to treat the patient on a slightly moving

surface, such as that provided by a ball, bolster, or

equilibrium board. The rationale of this technique is

twofold: 1) the slightly moving surface is relaxing,

probably like the effect of a rocking chair or other

gentle motion and 2) carefully graded and planned

movement of the supporting surface requires subtle

equilibrium responses as the patient adjusts to being

moved. With careful monitoring, normal muscle action to maintain balance may develop and the patient

with spasticity may learn to move in a more normal

way.14

The head-down or inverted position may be useful

for general inhibition of tone.16, 22, 23 Gellhorn describes the influence of increased blood pressure in

the head as stimulating the carotid sinus in the neck

and causing a generalized parasympathetic effect.23

Reduction of muscle tone is one result and can be

noted in small children during inversion for postural

drainage, for they often relax completely, some to the

point of falling asleep. Hyperactive or irritable children may be calmed in this position. A person with

hypertonus who can tolerate inversion may benefit

by the general reduction in tone, for movement may

be less restricted, muscles may relax, and potential

contractures may be easier to prevent.

880

Passive Lengthening

Three different approaches to avoid eliciting the

stretch reflex when lengthening a contracted muscle

have been described. There are times, however, when

none of these methods may be used, either because

the agonist is too weak to respond or because attempts

to inhibit the antagonist tone are unsuccessful. In

conditions of weakness or paralysis, the neurophysiological mechanism may be so disturbed that the

muscle may not respond to stimulation. Advanced

stages of muscular dystrophy and peripheral neuropathies are examples of disabilities that may require

direct passive lengthening because in each condition

the tight muscle and its opponent are unresponsive to

other measures of intervention.

If passive lengthening is selected as the appropriate

alternative, there are two kinds of techniques from

which to choose. One technique is prolonged holding

of the desired position at the point of maximum

tolerated length of the contracted muscle.10 The

stretch receptors of a muscle will become less sensitive

to stretch applied very slowly and maintained for a

long time.24 A variety of methods may be employed.

Orthoses and splints may be used to hold joints in

desired positions.14 Adaptive equipment may enable

an individual to function in certain positions more

readily. For example, a barrel chair for hip abduction

in sitting for a person with an adduction tendency or

a prone standing board for extension in weight bearing for persons with lower extremity flexor problems

may be effective. Individuals can be taught which

positions for sitting, sleeping, and other daily activities will be most helpful in correcting muscle shortness. For example, individuals with muscular dystrophy may be taught to use a long sitting position to

maintain hamstring muscle length. The advantages of

positioning are that it 1) avoids the position of contracture for the duration of the positioning, 2) may be

maintained over a long period so that treatment

effectiveness is prolonged, 3) may be incorporated

into the patient's daily routine, which increases the

likelihood of its being done regularly, and 4) is usually

painless.

If the above treatment suggestions are inapplicable

or ineffective, the technique of manual passive

stretching of the tight antagonist may be employed.4

Passive stretching is likely to be most effective in

individuals whose stretch reflex is inhibited, either by

cortical effort at relaxation or in paralytic conditions.

Very slowly applied passive stretch is likely to be the

most effective technique, for it should avoid eliciting

the stretch reflex and may cause the muscle to be

locally inhibited.24 An example of the latter is myelomeningocele, in which severe weakness or paralysis

PHYSICAL THERAPY

Downloaded from http://ptjournal.apta.org/ by guest on September 9, 2014

and tightness are often present in the same muscle.

Only positioning and passive exercises will be effective in gaining range at those joints that have no

active movement.

SUMMARY

Passive stretch to a contracted muscle has several

disadvantages. It does not improve active motion of

the opposing muscles and may elicit a stretch reflex

contraction in the contracted muscle if innervation to

the spinal cord is intact. This reflex contraction is

undesirable because it interferes with the desired

motion. Also, stretching is often painful.

Four approaches to reducing muscle contracture

have been described. Ideally, the weak opponent

muscle or agonist should be strengthened, if possible,

to enable it to move the joint through full range and

prevent recurrence or further development of the

muscle contracture. Other alternatives that may be

used before, or instead of, strengthening the weak

agonist include specific local inhibition to the contracted muscle or general inhibition to the limb or

entire body. If the stretch reflex can be inhibited, the

agonist may contract more easily and the tight muscle

may be stretched more easily and effectively. Finally,

prolonged maintenance in the desired position by

means of adaptive equipment and splints and performing activities of daily living may be more comfortable and more effective than passive manual

stretching because the procedures are carried out for

longer periods.

The variety of techniques available for treatment

of muscle contractures challenges physical therapists

to gain an understanding of the principles on which

the techniques are based and to develop skill in their

application. Research is needed to establish which

procedures are most effective for what kinds of problems, as well as to determine the scientific rationale

of procedures empirically found to be effective. Research may also lead to development of additional

techniques.

REFERENCES

1. Egli H: Basis for selection of mobilization technics. Phys Ther

Rev 3 8 : 7 5 9 - 7 6 1 , 1957

2. Adams RD: Diseases of Muscle: A Study in Pathology, ed 3.

Hagerstown, MD, Harper & Row, Publishers, 1975, pp 1 9 4 196

3. Rusk HA: Rehabilitation Medicine, ed 4. St. Louis, C.V.

Mosby Co, 1977, pp 9 8 - 1 0 2

4. Krusen FH, Kottke FJ, Ellwood PM: Handbook of Physical

Medicine and Rehabilitation, ed 2. Philadelphia, W.B. Saunders Co, 1971

5. Badell-Ribera A, Swinyard CA, Greenspan L, et al: Spina

bifida with myelomeningocele: Evaluation of rehabilitation

potential. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 4 5 : 4 4 3 - 4 5 3 , 1964

6. Wyke B: Neurological mechanisms in spasticity: A brief review of some current concepts. Physiotherapy 62:316-323,

1976

7. Rood MS: Neurophysiological mechanisms utilized in the

treatment of neuromuscular dysfunction. AJOT 10:220-224,

1956

8. Eldred E: Functional implications of dynamic and static components of the spindle response to stretch. Am J Phys Med

4 6 : 1 2 9 - 1 4 0 , 1967

9. Bobath B: Observations on adult hemiplegia and suggestions

for treatment. Physiotherapy 45:279-289, 1959.

10. Griffin JW: Use of proprioceptive stimuli in therapeutic exercise. Phys Ther 54:1072-1079, 1974

11. Knott M, Voss DE: Proprioceptive Neuromuscular Facilitation. New York, Harper & Row, Publishers, 1968

12. DeLorme TL: Restoration of muscle power by heavy resistance exercises. J Bone Joint Surg 27:645-667, 1945

13. Bobath K, Bobath B: The facilitation of normal postural

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

reactions and movements in the treatment of cerebral palsy.

Physiotherapy 50:246-262, 1964

Semans S: The Bobath concept in treatment of neurological

disorders. Am J Phys Med 46:732-785, 1967

Bishop B: Vibratory stimulation: Three possible applications

of vibration in treatment of motor dysfunctions. Phys Ther

5 5 : 1 3 9 - 1 4 3 , 1975

Stockmeyer SA: An interpretation of the approach of Rood

to the treatment of neuromuscular dysfunction. Am J Phys

Med 46:900-956, 1967

Skrotzky K, Gallenstein JS, Ostering LR: Effects of electromyographic feedback training on motor control in spastic

cerebral palsy. Phys Ther 58:547-559, 1978

Freeman MAR, Wyke B: Articular contributions to limb muscle reflexes. Br J Surg 53:61-69, 1966

Newton MJ, Lehmkuhl D: Muscle spindle response to body

heating and localized muscle cooling: Implications for relief

of spasticity. Phys Ther 45:91 - 1 0 5 , 1965

Tanigawa MC: Comparison of the hold-relax procedure and

passive mobilization on increasing muscle length. Phys Ther

52:725-735, 1972

Bobath B: The treatment of neuromuscular disorders by

improving patterns of coordination. Physiotherapy 5 5 : 1 8 22, 1969

Ayres AJ: Sensory Integration and Learning Disorders. Los

Angeles, Western Psychological Services, 1972, p 120

Gellhorn E: Principles of Autonomic-Somatic Integration.

Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 1967, pp 3 - 8

Harris FA: Facilitation techniques. In Basmajian JV (ed):

Therapeutic Exercise, ed 3. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins

Co, 1978, pp 1 0 4 - 1 0 5

Volume 60 / Number 7, July 1980

Downloaded from http://ptjournal.apta.org/ by guest on September 9, 2014

881

Review of Physical Therapy Alternatives for

Reducing Muscle Contracture

Dianne B Cherry

PHYS THER. 1980; 60:877-881.

Cited by

This article has been cited by 2 HighWire-hosted articles:

http://ptjournal.apta.org/content/60/7/877#otherarticles

Subscription

Information

http://ptjournal.apta.org/subscriptions/

Permissions and Reprints http://ptjournal.apta.org/site/misc/terms.xhtml

Information for Authors

http://ptjournal.apta.org/site/misc/ifora.xhtml

Downloaded from http://ptjournal.apta.org/ by guest on September 9, 2014

© Copyright 2025