CASE REPORT Cyclophosphamide Therapy for Corticoresistant Drug Reaction With

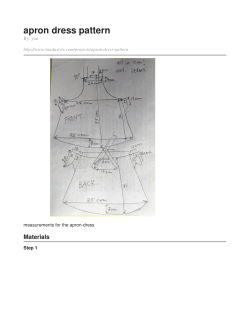

CASE REPORT Cyclophosphamide Therapy for Corticoresistant Drug Reaction With Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms (DRESS) Syndrome in a Patient With Severe Kidney and Eye Involvement and Epstein-Barr Virus Reactivation Emilie Laban, MD,1 Eva Hainaut-Wierzbicka, MD,1 François Pourreau, MD,2 Mokrane Yacoub, MD,3 Emilie Sztermer, MD,4 Gérard Guillet, MD,1Guy Touchard, MD,2 and Frank Bridoux, MD, PhD2 DRESS (drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms) syndrome is a severe adverse drug reaction with significant mortality, characterized by erythroderma, fever, lymphadenopathy, and visceral involvement. We report a case of multivisceral DRESS syndrome with posterior multifocal placoid pigment epitheliopathy and acute tubulointerstitial nephritis responsible for dialysis-dependent acute kidney failure in the context of reactivation of Epstein-Barr virus infection. Because of resistance of the skin and kidney manifestations to prolonged corticosteroid therapy, a 6-month course of oral cyclophosphamide resulted in complete recovery of all symptoms. To our knowledge, this is the first case showing the efficacy of cyclophosphamide in severe DRESS syndrome. Am J Kidney Dis 55:e11-e14. © 2010 by the National Kidney Foundation, Inc. INDEX WORDS: Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome; cyclophosphamide; kidney failure; acute interstitial nephritis; posterior multifocal placoid pigment epitheliopathy. D RESS (drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms) syndrome is a rare and severe drug-induced reaction with systemic involvement, mainly of the liver, lung, heart, and pancreas. DRESS syndrome, which also is known as drug hypersensitivity syndrome, typically appears after a 2- to 6-week exposure to a triggering drug. An increasing number of medications have been associated with DRESS syndrome, but most often the condition is triggered by anticonvulsants, allopurinol, and sulfasalazine. The mortality rate is estimated at 10%-20%.1 Kidney failure, mainly related to acute tubulointerstitial nephritis, occurs in 10% of cases, with recovery of kidney function usually obtained after withdrawal of the causative drug and corticosteroid therapy.2-6 We report a patient who developed corticosteroid-resistant DRESS syndrome with ocular and severe kidney involvement in the setting of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) reactivation. Treatment with cyclophosphamide resulted in complete resolution of symptoms. CASE REPORT A 48-year-old white woman was hospitalized for sudden vision loss and diffuse pruriginous maculopapular erythroderma with facial edema and palate erosions. Clinical examination findings otherwise were normal, with neither lymph- adenopathy nor fever. Her recent medical history included depression and recent tendonitis, for which she had used alprazolam (6 weeks before, for 1 day), fluoxetine (4 weeks before, for 1 day), and ibuprofen for 2 weeks before admission. Biological investigations showed hypereosinophilia (eosinophils, 1,700/L) and hepatitis (alanine aminotransferase, 87 IU/L; ␥-glutamyl-transpeptidase, 219 IU/L; and alkaline phosphatase, 270 IU/L). Serum creatinine level was 1.1 mg/dL (97 mol/L). Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), calculated using the 4-variable Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study equation, was 57 mL/min/1.73 m2 (0.95 mL/s/1.73 m2). Test results for antinuclear, anti-DNA, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies and cryoglobulins were negative. Complement levels were normal. Ophthalmologic tests showed bilateral decreased visual acuity (2/10) and anterior uveitis associated with acute posterior multifocal placoid pigment epitheliopathy From the Departments of 1Dermatology, 2Nephrology, Pathology, and 4Ophthalmology, CHU Poitiers, Poitiers, France. Received July 17, 2009. Accepted in revised form October 29, 2009. Originally published online as doi:10.1053/j.ajkd. 2009.10.054 on January 28, 2010. Address correspondence to Frank Bridoux, MD, PhD, Department of Nephrology, CHU Poitiers, Hôpital Jean Bernard, 2 rue de la milétrie, 86021 Poitiers, France. E-mail: f.bridoux@chu-poitiers.fr © 2010 by the National Kidney Foundation, Inc. 0272-6386/10/5503-0031$36.00/0 doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.10.054 3 American Journal of Kidney Diseases, Vol 55, No 3 (March), 2010: e11-e14 e11 e12 Laban et al Figure 1. Eye and kidney lesions. (A) Bilateral ocular fundi show bilateral acute posterior multifocal placoid pigment epitheliopathy with round lesions at the posterior pole. (B) Fluorescein angiography shows early hypofluorescence and late progressive impregnation of the lesions. (C, D) Kidney biopsy, light microscopy. (C) Acute interstitial nephritis with diffuse inflammatory infiltrate within the cortex (periodic acid–Schiff; original magnification, ⫻100). (D) Interstitial infiltrate shows numerous plasma cells, lymphocytes, macrophages, and severely damaged tubules (hematoxylin and eosin stain; original magnification, ⫻400). Fifteen days after admission (Fig 2), the patient developed severe kidney failure with a creatinine level of 5.1 mg/dL (453 mol/L, corresponding to an eGFR of 10 mL/min/1.73 m2 [0.17 mL/s/1.73 m2]), 24-hour urinary protein excretion of 0.22 g, and slight microscopic hematuria, associated with asymptomatic pancreatitis (lipase, 1,341 IU/L; normal, ⬍60 IU/L; and amylase, 793 IU/L; normal, ⬍100 IU/L). The eosinophil count was 5,900/L. Oral prednisone (1 mg/ kg/d) therapy led to a rapid decrease in serum lipase, eosinophil, and creatinine levels to 200 IU/L, 1,700/L, and Serum creatinine (µmol/L) (APMPPE; Fig 1A and B). Intraocular pressure was normal. A skin biopsy showed vacuolization of epidermal basal cells, lymphocytic exocytosis, and infiltration of the superficial dermis by mononuclear cells and eosinophils. Direct immunofluorescence study results were negative. Ibuprofen therapy was stopped on admission, and 3 intravenous methylprednisolone pulses (500 mg/d) resulted in improvement in skin lesions and correction of biological abnormalities within 5 days. However, skin eruption relapsed, accompanied by fever spikes. Blood cultures were negative. Drug exposure and main clinical manifestations: Therapy: IV corticosteroid pulses (days 2-3) Figure 2. Course of the case: drug exposure, clinical manifestations, and evolution of kidney function with treatment. Abbreviation: IV, intravenous. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Alprazolam Fluoxetine Ibuprofen Vision loss and erythroderma Acute myocarditis General condition recovering Oral corticosteroids (day 15 to month 6) IV cyclophosphamide (day 34) Oral cyclophosphamide (day 51 to month 6) Dialysis (day 31 to day 56) Cyclophosphamide in Severe DRESS Syndrome 2.3 mg/dL (203 mol/L; corresponding to an eGFR of 24 mL/min/1.73 m2 [0.40 mL/s/1.73 m2]), respectively. Kidney and abdominal ultrasound scans were normal. On day 27, while the patient was receiving 1 mg/kg of prednisone, she developed asymptomatic electrocardiographic signs characterized by T-wave inversion in the inferior territory without echocardiographic changes, but with a serum troponin-T level of 3.5 g/L (normal, ⬍0.01 g/L), suggestive of acute myocarditis. On day 31, serum creatinine level reached 5.7 mg/dL (502 mol/L; eGFR, 8 mL/min/1.73 m2 [0.13 mL/s/1.73 m2]). A kidney biopsy showed acute interstitial nephritis with diffuse interstitial inflammatory infiltrates composed of lymphocytes, plasma cells, macrophages, eosinophils, and neutrophils, focally showing a granulomatous pattern with scattered giant cells. Proximal and distal tubules showed severe tubulorrhexis. No viral inclusions were observed. Glomeruli, intrarenal arterioles, and arteries were unremarkable (Fig 1C and D). Immunohistochemical studies showed a prominent CD4⫹ T-cell infiltrate admixed with foci of CD8⫹ T cells, CD68⫹ macrophages, and CD20⫹ B cells. Results of immunofluorescence study with anti-immunoglobulin, C3, C1q, and C4d conjugates were negative. Computed tomography of the thorax, abdomen, and pelvis and bone marrow biopsy showed normal findings. Hemodialysis therapy was started on day 31. Prednisone (1 mg/ kg/d) was reinforced on day 34 by 1 intravenous pulse of cyclophosphamide (750 mg/m2), relayed by oral cyclophosphamide (100 mg/d) on day 51. Dialysis independence was obtained on day 56. Analysis of serum for cytomegalovirus and human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) DNA using polymerase chain reaction and tests for hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and HIV were negative. However, a significant increase in EBV DNA viral load (0.6 log) was detected between weeks 5 and 7 from admission. EBV immunoglobulin G level was 1,106 U/mL without detectable EBV immunoglobulin M (Polyantigenic Enzygnost; Dade-Behring, www.dadebehring.com). Results of immunohistochemical studies of the skin biopsy specimen using a specific anti-EBV latent membrane protein monoclonal antibody (Dako, www.dako.com) were negative. The patient’s general condition and visual acuity recovered after 3 months. Skin lesions disappeared and kidney function improved slowly with progressively tapered prednisone dosages and oral cyclophosphamide, which was stopped after 6 months. EBV viral load became undetectable at 6 months. Normalization of the eosinophil count was achieved only after introduction of cyclophosphamide. Ten months after admission, creatinine level was 1.2 mg/dL (102 mol/L) with eGFR of 53 mL/min/1.73 m2 (0.85 mL/s/1.73 m2) and 24-hour urine protein excretion was 0.2 g/d (Fig 2). DISCUSSION In the present case, the diagnosis of DRESS syndrome was established on the association of eosinophilia, erythroderma, and systemic symptoms, including hepatic, pancreatic, cardiac, and kidney manifestations. Although a role for alprazolam and fluoxetine was not fully excluded, e13 ibuprofen was the most likely causative drug.7 Contrasting with the usual manifestations of DRESS syndrome, the clinical presentation was marked by severe ocular lesions followed by dialysis-dependent kidney failure despite rapid withdrawal of the culprit drugs and steroid therapy. Ocular involvement is a rare feature of DRESS syndrome, with only 2 previously reported cases, both induced by lamotrigine. Schauer et al8 described a 63-year-old woman with DRESS syndrome, acute bilateral panuveitis, increased intraocular pressure, and decreased visual acuity, associated with HHV-6 reactivation. Complete recovery was obtained after withdrawal of the anticonvulsant drug. Gitteau et al9 reported an epileptic 19-year-old woman with acute bilateral vision loss related to APMPPE 4 weeks after the introduction of lamotrigine therapy. General and ophthalmologic recovery occurred 6 weeks after lamotrigine therapy withdrawal and oral prednisone. APMPPE is a rare entity characterized by bilateral multifocal yellowish-white placoid lesions of the retinal pigment epithelium. It is associated with various conditions, including systemic vasculitis, sarcoidosis, ulcerative colitis, streptococcal infections, and after vaccination.10 In the present case, the severe loss in visual acuity was secondary to both uveitis and APMPPE, without increased intraocular pressure. No infectious or autoimmune cause was found, and EBV reactivation was diagnosed 5 weeks from the onset of symptoms. Visual recovery occurred 50 days after drug withdrawal with corticosteroid plus cyclophosphamide therapy, suggesting that druginduced hypersensitivity should be considered as a potential cause of APMPPE. Kidney involvement in patients with DRESS syndrome usually is mild, but some patients may develop severe kidney failure.2-6 As described here, kidney failure may be delayed and occur after corticosteroid therapy withdrawal. Kidney biopsy, rarely performed, shows acute immunoallergic interstitial nephritis associated with tubular necrosis in patients with dialysis-dependent kidney failure.3,6 In this case, kidney involvement was particularly severe, characterized by diffuse interstitial inflammation with focal granuloma and extensive acute tubular necrosis, which probably accounted for the prolonged kidney failure and resistance to corticosteroid treatment. e14 Laban et al DRESS syndrome frequently is associated with reactivation of HHV, particularly HHV-6, and less commonly cytomegalovirus and EBV.7,11 However, the pathogenic role of viral infection is unknown. It has been suggested that reactivation of herpesvirus may modify drug metabolism, induce the production of reactive metabolites, and enhance drug-induced T-cell activation, resulting in the prolonged course and recurrence of the disease.12 In the present case, EBV replication, which was detected 5 weeks from the onset and probably was favored by steroid-induced immunosuppression, might have enhanced the diffusion and severity of systemic symptoms. Treatment of DRESS syndrome is based on rapid withdrawal of the drug implicated as the causative agent, with a delayed stop associated with poor prognosis. Systemic corticosteroid therapy, commonly used in patients with severe visceral involvement, should be used with caution because of the risk of recurrence through viral reactivation.1,7,11 In the case of steroid-resistant life-threatening symptoms, in patients with active herpesvirus infection, the indication and choice of immunomodulating or immunosuppressive therapies is challenging. Various agents, such as intravenous immunoglobulins12 and cyclosporine,13 have been used successfully. To our knowledge, the present observation is the first showing a beneficial effect of cyclophosphamide in patients with DRESS syndrome. Cyclophosphamide, an alkylating drug capable of slowing or stopping cell growth of lymphocytes and polymorphonuclear leukocytes, has shown efficacy in various autoimmune diseases.14 Because tolerance was good without increased EBV replication, cyclophosphamide deserves to be added as an effective therapeutic option in DRESS syndrome with severe systemic and kidney involvement resistant to steroid therapy. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Support: This work was supported by a grant from AREN Poitou-Charentes. Financial Disclosure: The authors declare that they have no relevant financial interests. REFERENCES 1. Eshki M, Allanore L, Musette P, et al. Twelve-year analysis of severe cases of drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms: a cause of unpredictable multiorgan failure. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145(1):67-72. 2. Ghislain PD, Bodarwe AD, Vanderdonckt O, Tennstedt D, Marot L, Lachapelle JM. Drug-induced eosinophilia and multisystemic failure with positive patch-test reaction to spironolactone: DRESS syndrome. Acta Derm Venereol. 2004;84(1):65-68. 3. Garnier A, El Marabet el H, Kwon T, et al. Acute renal failure in a 3-year-old child as part of the drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome following hepatitis A. Pediatr Nephrol. 2008;23(4):667-669. 4. Vauthey L, Uçkay I, Abrassart S, et al. Vancomycininduced DRESS syndrome in a female patient. Pharmacology. 2008;82(2):138-141. 5. Vaida I, Roszkiewicz F, Gruson B, Makdassi R, Damaj G. Drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms after chlorambucil treatment in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Pharmacology. 2009;83(3):148-149. 6. Augusto JF, Sayegh J, Simon A, et al. A case of sulphasalazine-induced DRESS syndrome with delayed acute interstitial nephritis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24(9): 2940-2942. 7. Descamps V, Valance A, Edlinger C, et al. Association of human herpes virus 6 infection with drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms. Arch Dermatol. 2001; 137(3):301-304. 8. Schauer P, Salaun N, Bazin S, Labrouze JM, Bourguignon G. DRESS syndrome with bilateral panuveitis, elevated intraocular pressure, and HHV-6 reactivation: a case report. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2006;29(6):659-664. 9. Gitteau Lala E, Cussenot B, Majzoub S, et al. DRESS syndrome and acute posterior multifocal placoid pigment epitheliopathy (APMPPE): a case report [abstract]. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2007;30:287A. 10. Quillen DA, Davis JB, Gottlieb JL, et al. The white dot syndromes. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;137(3):538-550. 11. Descamps V, Mahe E, Houhou N, et al. Drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome associated with Epstein-Barr virus infection. Br J Dermatol. 2003;148(5):1032-1034. 12. Fields KS, Petersen MJ, Chiao E, Tristani-Firouzi P. Case reports: treatment of nevirapine-associated DRESS syndrome with intravenous immune globulin (IVIG). J Drugs Dermatol. 2005;4(4):510-513. 13. Zuliani E, Zwahlen H, Gilliet F, Marone C. Vancomycin-induced hypersensitivity reaction with acute renal failure: resolution following cyclosporine treatment. Clin Nephrol. 2005;64(2):155-158. 14. Allison AC. Immunosuppressive drugs: the first 50 years and a glance forward. Immunopharmacology. 2000; 47(2-3):63-83.

© Copyright 2025