Prescriptions of Chinese Herbal Medicine for Constipation Under the National Health

ORIGINAL

ARTICLE

Prescriptions of Chinese Herbal Medicine for

Constipation Under the National Health

Insurance in Taiwan

Maw-Shiou Jong1,5, Shinn-Jang Hwang2,4, Yu-Chun Chen2,4, Tzeng-Ji Chen2,4,

Fun-Jou Chen3, Fang-Pey Chen1,5*

1

Center for Traditional Medicine, 2Department of Family Medicine, Taipei Veterans General Hospital, Taipei;

3

Graduate Institute of Integrated Chinese and Western Medicine, Chinese Medical University, Taichung;

4

Division of Family Medicine, Department of Medicine, and 5Institute of Traditional Medicine,

National Yang-Ming University School of Medicine, Taipei, Taiwan, R.O.C.

Background: Constipation is a common gastrointestinal problem worldwide. The aim of this study was to determine the

frequency of use and prescriptive patterns of Chinese herbal medicine (CHM) in treating constipation by analyzing the

claims data of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) from the National Health Insurance (NHI) in Taiwan.

Methods: The computerized claims dataset of the TCM office visits and the corresponding prescription files in 2004

compiled by the NHI Research Institute in Taiwan were linked and processed. Visit files with the single diagnostic coding

of constipation (ICD-9-CM code 564.0) were extracted to analyze the frequency and pattern of corresponding CHM prescriptions. The association rule was applied to analyze the co-prescription of CHM in treating constipation.

Results: There were 152,564 subjects who visited TCM clinics only for constipation in Taiwan during 2004 and received

a total of 387,268 CHM prescriptions. Subjects between 20 and 29 years of age comprised the largest number of those

treated (25.5%). Female subjects used CHM for constipation more frequently than male subjects (female:male = 3.31:1).

There was an average of 4.6 items of single Chinese herbs or formula in a single prescription for constipation. Ma-zi-renwan was the most commonly prescribed herbal formula, while Da-huang (Rheum palmatum) was the most commonly

used single Chinese herb. According to the association rule, the most common prescribed pattern of 2-drug combination

of CHM for treating constipation was Ban-xia-xie-xin-tang plus Ma-zi-ren-wan, while the 3-drug combination of CHM was

Fang-feng-tong-sheng-san, Rheum palmatum and Ma-zi-ren-wan.

Conclusion: This study showed the pattern of single Chinese herbs or herbal formulae used in treating constipation

in Taiwan. Further clinical trials are needed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of these CHMs in treating constipation.

[J Chin Med Assoc 2010;73(7):375–383]

Key Words: Chinese herbal medicine, constipation, pharmacoepidemiology, traditional Chinese medicine

Introduction

Constipation is a condition in which bowel movements

are infrequent, irregular, or difficult.1 It is a disorder

resulting from different causes such as insufficient

intake of dietary fiber, emotional influence, dysfunction

of the nervous system, structural abnormality, systemic

disease, or drug effects.1 Constipation is a common

gastrointestinal problem worldwide, and it affects at

least 8.5% of individuals in Taiwan, based on Rome II

diagnostic criteria.2 It often occurs in females, with

advanced age, low socioeconomic class and low educational position.2,3

The aim of treating constipation is to treat the underlying causes, improve symptoms, and resume the

normal physiological function of the bowel. Treating

constipation can be a comprehensive therapy tailored to

the individual.4 Drugs commonly used include bulk laxatives, osmotic laxatives, non-absorbable sugar, stimulant laxatives, cholinergic agents and other prokinetic

*Correspondence to: Dr Fang-Pey Chen, Center for Traditional Medicine, Taipei Veterans General

Hospital, 201, Section 2, Shih-Pai Road, Taipei 112, Taiwan, R.O.C.

E-mail: fpchen@vghtpe.gov.tw

Received: December 9, 2009

Accepted: June 22, 2010

●

J Chin Med Assoc • July 2010 • Vol 73 • No 7

© 2010 Elsevier Taiwan LLC and the Chinese Medical Association. All rights reserved.

●

375

M.S. Jong, et al

agents. Selective chloride channel activators, which can

increase intestinal water secretion, thereby increasing

intestinal motility and facilitating the bowel movement,

are also used.4,5

After excluding secondary constipation caused by

other problems, primary (idiopathic) constipation can

be classified into 3 categories: normal transit or irritable bowel syndrome, pelvic floor dysfunction, and slow

transit constipation. These 3 types of constipation overlap frequently. Normal and slow transit constipation are

usually treated by the drugs mentioned above.5 In

Eastern countries, traditional Chinese medicine (TCM)

is another option in addition to Western medicine for

treating constipation.6 The principles of diagnosis and

treatment of constipation in TCM are primarily based

on the manifestations of the syndrome Therefore, the

principal signs and symptoms of patients from which

a corresponding prescription of Chinese herbal medicine (CHM) is provided, is largely dependent on the

experience of the Chinese herbal doctors or from the

records of ancient Chinese books. The optimal choice

of CHM prescription for constipation is unknown.

Furthermore, whether these Chinese herbs or formulae

have modern pharmacological effects in the treatment

of constipation remains to be elucidated.

In Taiwan, the National Health Insurance (NHI)

has reimbursed medical expenses for Western medicine

for nearly all inhabitants since 1995 (22,134,270 beneficiaries at the end of 2004, covering nearly 98% of the

total population in Taiwan).7,8 The use of TCM has

been reimbursed by the NHI since 1996. People in

Taiwan are free to choose Western medicine or TCM,

and are allowed to visit primary care clinics or hospitals

without referral. Because all claims data are available to

researchers in electronic form, a large-scale survey of

pharmacoepidemiological issues can be easily conducted. The aim of the current study was to explore the

frequency and pattern of CHM use for subjects with

constipation by analyzing the NHI database in 2004 in

Taiwan.

(CM_CD2004.DAT and CM_OO2004.DAT), for

2004 from the NHIRD in Taiwan. The visit files recorded the dates of encounters, the medical care facilities and specialties, patients’ sex, birth date, and up to 3

diagnoses according to the International Classification

of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9CM). For privacy protection, the identification data of

patients and institutions was scrambled cryptographically to ensure anonymity. The prescription files contained the prescription records of CHM corresponding

to the office visits. A CHM prescription contains 1 to

several single Chinese herbs or herbal formulae. The

Chinese herbal formulae or single herbs are made in

powder or fine granules in Taiwan, and can be easily

mixed and dispensed into small packages so that 1 prescription can be taken at a time.

All TCMs are provided only in ambulatory clinics

under the coverage of NHI in Taiwan and there is no

inpatient care. In addition, only licensed TCM physicians are qualified for reimbursement. The insurance

benefits of TCM in Taiwan include CHM, acupuncture

and traumatology manipulative therapy, especially for

joint dislocation.

Study design

Methods

Although the concept of disease entities in TCM is

quite different from that in Western medicine, the

TCM physicians in Taiwan are requested to make the

diagnosis based on ICD-9-CM coding for visiting

claims. In this study, we utilized the data of subjects

with the single diagnostic code for constipation (i.e.

ICD-9 code 564.0) among TCM visits.

According to the theory of TCM, a single prescription from a TCM physician may contain a single Chinese herb or multiple herbs of various dosages, namely

a compound (Fu-Fang) or a classical formula (regimen,

remedy or Fang-Ji). These are a combination of compatible Chinese herbs in fixed dosages ascribed to classical or well-known Chinese textbooks of medicine, or

a classical formula plus some Chinese herbs called ChiaChien-Fang. In addition, several formulae can be put

together with or without 1 or several Chinese herbs for

different symptoms and signs manifested by a patient.

Data sources

Data analysis

The NHI program in Taiwan was initiated in 1995, and

the Bureau of the NHI began to release all claims data

in electronic form to the public under the National

Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) project

since 1999. The structure of the claims files is described

in detail on the NHIRD website and in our previous

report.6 Briefly, we obtained the database of TCM

claims, including the visit files and prescription files

The database software, IBM DB2 version 8.1 (IBM,

Armonk, NY, USA), was used for data linkage and processing. Regular statistics (mean and percentage) were

displayed for the frequency of use and pattern of CHM

prescriptions for constipation. Association rule mining, originally developed in the 1990s to identify which

groups or sets of items were likely to be purchased

together in the market, was applied to calculate the

376

J Chin Med Assoc • July 2010 • Vol 73 • No 7

Chinese herb use for constipation in Taiwan

prescription of the Chinese herbs for constipation.9,10

An association rule was applied to prescriptions as follows: when a physician prescribes drug A (or drugs

{A1,A2}, drugs {A1,A2,A3}, etc.), he/she will also prescribe drug B in X% of cases, and this co-prescribing is

present in Y% of all prescriptions. The support factor

is the ratio of co-prescriptions of all prescriptions (i.e.

Y% in the above example). The confidence factor is the

ratio of co-prescriptions to prescriptions for drug A

(i.e. X% in the above example). For executing the program to identify association rules in our dataset, we

chose 0.5% as the minimum support factor and 30%

as the minimum confidence level.11

Mu-xiang-bin-lang-wan (4.8%), San-huang-xie-xin-tang

(4.7%), Tao-ren-cheng-qi-tang (4.6%), and Gan-luyin (4.5%; Table 2).

Single Chinese herbs

The most common single Chinese herb prescribed

for constipation was Rheum palmatum (Da-huang)

(18.4%), followed by Magnolia officinalis (Hou-pu)

(6.6%), Scrophularia ningpoensis (Xuan-shen) (6.3%),

Citrus aurantium (fruit; Zhi-shi) (6.1%), Rehmannia

glutinosa (Sheng-di-huang) (6.0%), Ophiopogon japonicus (Mai-dong) (6.0%), Crataegus pinnatifida (Shanzha) (5.7%), Cannabis sativa (Huo-ma-zen) (5.1%),

Glycyrrhiza uralensis (Gan-cao) (5.0%), and Citrus

aurantium (peel; Zhi-ke) (4.5%; Table 3).

Results

Combination of CHM

Epidemiology

Among the 22,134,270 valid beneficiaries of the NHI

at the end of 2004 in Taiwan, 6,224,436 (28.1%) subjects had used TCM during that year, and 152,564

(2.5%) subjects visited the TCM clinics and used CHM

only for constipation. Among these constipation subjects, there were a total of 387,268 CHM prescriptions.

The peak age of subjects with constipation treated by

TCM was between 20 and 29 years of age (25.5%), followed by 30–39 years of age (19.4%), and 40–49 years

of age (15.7%; Table 1). Female subjects used CHM

for constipation more frequently than male subjects

(female:male = 3.31:1).

Chinese herbal formulae

Ma-zi-ren-wan (34.4%) was the most commonly prescribed Chinese herbal formula for subjects with

constipation, followed by Fang-feng-tong-sheng-san

(17.6%), Run-chang-wan (12.4%), Run-chang-tang

(7.7%), Da-chai-hu-tang (6.6%), Ping-wei-san (4.9%),

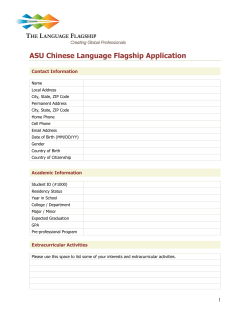

There was an average of 4.6 Chinese herbal items in a

single prescription for subjects with constipation. The

most common number of items in the prescription of

Chinese herbal formulae or single Chinese herbs for

subjects with constipation in Taiwan is 5 (16.6%), followed by 4 (16.5%), and 3 (15.3%; Figure 1). According to the association rule, the most commonly

prescribed pattern of a 2-drug combination of CHM

for treating constipation was Ban-xia-xie-xin-tang plus

Ma-zi-ren-wan (Table 4), while the 3-drug combination of CHM was Fang-feng-tong-sheng-san, Rheum

palmatum and Ma-zi-ren-wan (Table 5). The most

common 4-drug combination of CHM for constipation was Ophiopogon japonicus, Rehmannia glutinosa,

Scrophularia ningpoensis and Run-chang-wan, which

accounted for 0.3% of all prescriptions. The most common 5-drug combination of CHM was An-zhong-san,

Mu-xiang-bin-lang-wan, Run-chang-tang, Fang-fengtong-sheng-san and Ma-zi-ren-wan, which accounted

for 0.2% of all prescriptions.

Table 1. Age-specific frequency of the use of TCM in patients with constipation in Taiwan during 2004*

Subjects with constipation using TCM

Age (yr)

0–9

10–19

20–29

30–39

40–49

50–59

60–69

70–79

≥ 80

Total

Total patients

Males†

Females†

11,013 (7.2)

16,713 (11.0)

38,961 (25.5)

29,969 (19.6)

23,938 (15.7)

11,607 (7.6)

7,621 (5.0)

8,968 (5.9)

3,774 (2.5)

152,564 (100)

4,997 (3.3)

3,716 (2.4)

4,203 (2.8)

4,279 (2.8)

4,480 (2.9)

3,311 (2.2)

3,275 (2.1)

5,131 (3.4)

1,978 (1.3)

35,370 (34.05)

6,016 (3.9)

12,997 (8.6)

34,758 (22.7)

25,690 (16.8)

19,458 (12.8)

8,296 (5.4)

4,346 (2.9)

3,837 (2.5)

1,796 (1.2)

117,194 (65.95)

*Data presented as n (%); †male:female ratio is 1:3.31. TCM = traditional Chinese medicine.

J Chin Med Assoc • July 2010 • Vol 73 • No 7

377

M.S. Jong, et al

Table 2. Top 10 Chinese herbal formulae prescribed for constipation in Taiwan during 2004*

Chinese herbal formulae

(Chinese name)

Ma-zi-ren-wan

Fang-feng-tong-sheng-san

Run-chang-wan

Run-chang-tang

Da-chai-hu-tang

Ping-wei-san

Mu-xiang-bin-lang-wan

San-huang-xie-xin-tang

Tao-ren-cheng-qi-tang

Gan-lu-yin

Ingredients

Prescriptions, n (%)

Cannabis sativa, Paeonia lactiflora, Citrus aurantium, Rheum palmatum,

Magnolia officinalis, Prunus armeniaca

Saposhnikovia divaricata, Forsythia suspenae, Gardenia jasminoides,

Schizonepeta tenuifolia, Ephedra sinica, Ligusticum chuanxiong, Angelica

sinensis, Paeonia lactiflora, Atractylodes macrocephala, Rheum palmatum,

Mirabilite, Scutellaria baicalensis, Talcum, Gypsum Fibrosum, Mentha

haplocalyx, Platycodon grandiflorum, Glycyrrhiza uralensis, Zingiber officinale

Angelica sinensis, Notopterygium incisum, Rheum palmatum, Prunus persica,

Cannabis sativa

Rheum palmatum, Angelica sinensis, Rehmannia glutinosa, Cannabis sativa,

Prunus persica, Prunus armeniaca, Citrus aurantium, Scutellaria baicalensis,

Magnolia officinalis, Glycyrrhiza uralensis

Bupleurum chinense, Scutellaria baicalensis, Paeonia lactiflora, Pinellia ternate,

Citrus aurantium, Rheum palmatum, Ziziphus jujuba, Zingiber officinale

Atractylodes lancea, Magnolia officinalis, Citrus reticulate, Glycyrrhiza uralensis,

Zingiber officinale, Ziziphus jujuba

Saussurea lappa, Areca cathechu, Rheum palmatum, Coptis chinensis,

Phellodendron amurense, Cyperus rotundus, Ipomoea nil, Citrus reticulate,

Citrus reticulate (unripe), Curcuma phaeocaulis, Citrus aurantium, Sparganium

stoloniferum, Mirabilite

Rheum palmatum, Coptis chinensis, Scutellaria baicalensis

Prunus persica, Rheum palmatum, Cinnamomum cassia, Glycyrrhiza

uralensis, Mirabilite

Rehmannia gultinosa, Asparagus cochinchinensis, Ophiopogon japonicus,

Dendrobium nobile, Artemisia scoparia, Eriobotrya japonica, Scutellaria

baicalensis, Citrus aurantium, Glycyrrhiza uralensis

133,288 (34.4)

68,264 (17.6)

47,870 (12.4)

29,927 (7.7)

25,504 (6.6)

18,885 (4.9)

18,689 (4.8)

18,081 (4.7)

17,935 (4.6)

17,482 (4.5)

*Total number of prescriptions = 387,268.

Table 3. Top 10 single Chinese herbs prescribed for constipation in Taiwan during 2004*

Single Chinese herb (Chinese name)

Generic name

Da-huang

Hou-pu

Xuan-shen

Zhi-shi (fruit)

Sheng-di-huang

Mai-dong

Shan-zha

Huo-ma-zen

Gan-cao

Zhi-ke (peel)

Rheum palmatum

Magnolia officinalis

Scrophularia ningpoensis

Citrus aurantium

Rehmannia glutinosa

Ophiopogon japonicus

Crataegus pinnatifida

Cannabis sativa

Glycyrrhiza uralensis

Citrus aurantium

Prescriptions, n (%)

71,133 (18.4)

25,379 (6.6)

24,528 (6.3)

23,443 (6.1)

23,212 (6.0)

23.052 (6.0)

22,055 (5.7)

19,708 (5.1)

19,273 (5.0)

17,501 (4.5)

*Total number of prescriptions = 387,268.

Discussion

The current study, the first large-scale survey of the

use of CHM in the treatment of constipation in a

Chinese population, analyzed the claims dataset of

TCM office visits covered by the NHI in Taiwan. Our

results showed that females were dominant among

TCM users, which is in agreement with the results of

378

a systematic review by Peppas et al,3 who reported that

for those aged between 20 and 29 years, the femaleto-male ratio was 8.1. Chiarelli et al12 proposed that

hormonal factors may contribute to constipation in

women. Progesterone secreted during the luteal phase

of the menstrual cycle or during gestation is thought to

decrease the intestinal transit time, leading to constipation.12 In addition, we also found that most people

J Chin Med Assoc • July 2010 • Vol 73 • No 7

Chinese herb use for constipation in Taiwan

80,000

70,000

63,853 64,227

59,172

60,000

Number of prescriptions

54,187

49,405

50,000

40,000

33,968

30,000

26,663

18,926

20,000

8,553

10,000

4,105

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

≥10

Number of Chinese herbal formulae or

single herbs in a single prescription

Figure 1. The number of combinations of Chinese herbal medicine related to the number of prescriptions. The most common combination of Chinese herbal medicine used for treating constipation was 5, followed by 4 and then 3 items of Chinese herbal formulae or single herbs. There was a mean of 4.6 Chinese herbal items in a single prescription for subjects with constipation.

Table 4. Most common prescription patterns of a 2-drug combination of Chinese herbs in a single prescription for constipation in

Taiwan during 2004*

Chinese herbal formulae or single herbs

Ban-xia-xie-xin-tang plus Ma-zi-ren-wan

Shao-yao-gan-cao-tang plus Ma-zi-ren-wan

Yi-zi-tang plus Ma-zi-ren-wan

Platycladus orientalis plus Ma-zi-ren-wan

San-huang-xie-xin-tang plus Ma-zi-ren-wan

Xie-fu-zhu-yu-tang plus Ma-zi-ren-wan

Liu-wei-di-huang-wan plus Ma-zi-ren-wan

Gan-lu-yin plus Run-chang-wan

Da-huang-mu-dan-pi-tang plus Ma-zi-ren-wan

Cyperus rotundus plus Ma-zi-ren-wan

Support (%)

Prescription number

0.7

0.7

0.6

0.6

0.6

0.6

0.6

0.6

0.5

0.5

2,855

2,781

2,441

2,301

2,297

2,209

2,203

2,150

2,097

2,087

*Total number of prescriptions = 387,268.

using TCM for constipation were between 20 and

29 years of age (25.5%), followed by those between

30 and 39 years of age (19.6%), with the majority being

females. This result is different from the findings

reported by Higgins and Johanson,13 who showed an

increase in the prevalence of constipation with age.

Further studies are needed to clarify this issue and reveal

other causes.

J Chin Med Assoc • July 2010 • Vol 73 • No 7

Rheum palmatum, the most common single Chinese

herb for constipation, is also a component of 8 of the 10

most commonly used herbal formulae for constipation.

Rheum palmatum was first recorded in the classical

Chinese medical tome “Shennongbencaojing”, the earliest Materia Medica in China, before 25–225 AD. At

that time, Rheum palmatum was used as a type of purgative agent. The major bioactive constituents of Rheum

379

M.S. Jong, et al

Table 5. Most common prescription patterns of a 3-drug combination of Chinese herbs in a single prescription for constipation in

Taiwan during 2004*

Chinese herbal formulae or single herbs

Fang-feng-tong-sheng-sa, Rheum palmatum and Ma-zi-ren-wan

Angelica sinensis, Cistanche tubulosa and Ma-zi-ren-wan

Citrus aurantium, Magnolia officinalis and Ma-zi-ren-wan

Rehmannia glutinosa, Fang-feng-tong-sheng-san and Rheum palmatum

Areca catechu, Saussurea lappa and Ma-zi-ren-wan

Da-chai-hu-tang, Fang-feng-tong-sheng-san and Rheum palmatum

Crataegus pinnatifida, Fang-feng-tong-sheng-san and Ma-zi-ren-wan

Run-chang-tang, Rheum palmatum and Ma-zi-ren-wan

Citrus aurantium, Rheum palmatum and Ma-zi-ren-wan

Run-chang-wan, Rheum palmatum and Ma-zi-ren-wan

Support (%)

Prescription number

0.6

0.5

0.4

0.3

0.3

0.3

0.3

0.3

0.3

0.3

2,462

1,817

1,405

1,280

1,223

1,177

1,164

1,083

1,074

1,060

*Total number of prescriptions = 387,268.

palmatum are phenolic compounds, among which sennosides and anthraquinone glycosides are considered to

be the main purgative components.14 This stimulant laxative or its metabolites in the human body can stimulate the intestinal wall, enhance intestinal peristalsis, or

change the transport of liquid and electrolytes, thereby

enhancing gastrointestinal secretion and leading to

purgation.15 Besides Rheum palmatum, other Chinese

herbs also have the ability to modulate gastrointestinal

function. Mirabilite (sodium sulfate decahydrate) has

been reported to have osmotic laxative activity through

poor absorption of sulfate, which increases osmotic pressure and results in water and electrolytes being retained

in the intestinal cavity.16 Ipomoea nil extracts may affect

the ion transport of rat intestinal epithelia, leading to

water movement.17 The aqueous crude extract of

Prunus persica possesses spasmogenic activity in isolated

guinea pig ileum, which may be partially through the

cholinergic pathway.18 In animal experiments, the constituent arecoline in Areca catechu can stimulate colonic

motility through muscarinic acetylcholine receptors.19

Angelica sinensis may possess the ability to react with

serotonin receptors and then promote serotonergic

activity, thereby stimulating intestinal motility.20,21

The active ingredient in Rehmannia glutinosa,

catalpol, is an iridoid glycoside,22,23 and Gardenia jasminoides, which contains iridoid, may also possess purgative activity.24 In ritonavir-treated rats with slower

gastric emptying capability, gastrointestinal dysfunction

is improved after administration of a Scutellaria baicalensis extract.25 Zingiber officinale can speed up gastrointestinal transit in mice fed with a charcoal meal.26

The water-soluble components of Zizyphus jujuba can

reduce gastrointestinal transit time, thus enhancing

water retention in feces.27

The components of commonly used herbal formulae for treating constipation mostly have a purgation

380

effect, as described above by modern pharmacology.

However, there are some Chinese herbs that have an

opposite pharmacological function. For example, cannabidiol is a Cannabis sativa-derived compound that

can selectively inhibit croton oil-induced intestinal

hypermotility in mice,28 and decrease gastrointestinal

movement.29 Cyperus rotundus possesses antidiarrheal

activity.30 These Chinese herbs, which decrease gastrointestinal movement, have been used for the treatment

of constipation. Different pharmacological functions

may be due to the difference between a pure compound

and a crude extract of the herb, or the combined effects

of multi-component formulations, or through different

pathological mechanisms. How 1 Chinese herb can

exert effects that are diametrically opposed is still not

fully understood and deserves further investigation.

Glycycoumarin is 1 active component in Glycyrrhiza

uralensis. It has an antispasmodic effect on the contraction of mouse jejunum through inhibition of the

phosphodiesterase 3 mechanism.31 Other Chinese

medicines such as Magnolia officinalis,32 Mentha sp.,33

and Paeonia lactiflora34 have a spasmolytic effect, which

could possibly be beneficial for spasmodic constipation.35 In isolated animal tissue, the aqueous-methanol

crude extract of Saussurea lappa possesses a spasmogenic

effect through the cholinergic pathway. However,

under conditions such as a higher drug concentration

or intestinal hypermotility, the spasmolytic effect appears through a calcium channel blocker mechanism.36

Therefore, even for the same Chinese herb, there may

be different pharmacological functions with different

dosages or physical conditions.

Among the top 10 single Chinese herbs prescribed

for constipation, Scrophularia ningpoensis contains a

bioactive compound, iridoid, which possibly possesses

a purgative effect,23 and Crataegus pinnatifida was

once reported to have an antispasmodic effect.37 In the

J Chin Med Assoc • July 2010 • Vol 73 • No 7

Chinese herb use for constipation in Taiwan

classification of Chinese medicine, Ophiopogon japonicus is categorized as a Yin-tonifying medicinal, capable of nourishing Yin fluid and therefore moistening

the intestine.

In the top 10 Chinese herbal formulae prescribed

for constipation, Fang-feng-tong-sheng-san (Bofutsusho-san in Japanese) is usually used to combat

obesity.38 Da-chai-hu-tang extracts and San-huangxie-xin-tang extracts relax smooth muscle tone in the

gastrointestinal tract through phosphodiesterase inhibition, and are therefore capable of treating spasmodic

constipation.39 Ping-wei-san is usually applied for the

treatment of heartburn and gastritis.40 It is worth noting that Fang-feng-tong-sheng-san and Da-chai-hu-tang

have been reported to cause interstitial pneumonia or

hepatitis during clinical practice.41,42 It is often difficult

to completely understand the underlying mechanisms.

Therefore, it is necessary to conduct randomized,

double-blinded, placebo-controlled trials to assess the

efficacy and safety of these Chinese medicines in patients

with constipation. Additionally, Cistanche tubulosa contains iridoid glycosides, and thus possibly has purgative effects.43 Ban-xia-xie-xin-tang is reported to have

antidiarrheal activity,44 and Shao-yao-gan-cao-tang has

an antispasmodic effect.45

In our study, an average of 4.6 items, either Chinese

herbal formulae or single herbs, were contained in each

prescription for constipation. According to our results,

the most commonly prescribed CHM drug combination for treating constipation was mainly an herbal

formula and single herb.

This study was a retrospective analysis of the use of

CHM to treat constipation. Unlike clinical trials, which

can provide direct evidence of efficacy, many herbs in

the herbal formulae or single herbs frequently prescribed have been found to contain ingredients that assist defecation via varied mechanisms as discussed above.

In fact, the principle of TCM treatment is different

from that of Western medicine, as TCM involves the

patient’s constitutional needs, e.g. Bianzheng Lunzhi

(ᙃᢞᓵए, syndrome differentiation and treatment),46

and therefore, it is difficult to create a constitutionallymatched control group. With regard to the treatment

of constipation, although Chinese and Western medicine view the causes of the disease differently, both are

in agreement that constipation is a symptom rather than

a diagnosis. TCM treatment for constipation is based

on the syndrome of its subclassification; for example, if

the symptoms include a dry mouth, yellow urine, a red

tongue and surging pulse, it is subclassified as excess

syndrome (ኔᢞ) for which a formula such as Ma-zi-renwan can be prescribed, as it can discharge excessive

heat.47 On the other hand, if the symptoms include

J Chin Med Assoc • July 2010 • Vol 73 • No 7

fatigue, a pale complexion, pale tongue and a thready,

weak pulse, it is subclassified as deficient syndrome

(ဠᢞ). Therefore, a formula or single herb that can nourish Qi and Yin will be administered; in this case, Runchang-tang or Ophiopogon japonicus is a good choice.

In young people, constipation is mostly subclassified

as excess syndrome, which may explain why this study

found Ma-zi-ren-wan to be the formula most commonly prescribed for the treatment of constipation.

In conclusion, based on the availability of electronic

health care claims data in Taiwan, a population-based

survey of Chinese herbal pharmacoepidemiology on

constipation determined the frequency of use and patterns of prescriptions in a Chinese population. Nevertheless, the therapeutic effects and safety of those herbal

formulae or single herbs used requires further elucidation through efficiency-based clinical studies or

well-designed randomized, double-blinded, placebocontrolled trials.

Acknowledgments

This study was based on a portion of data from the

NHI Research Database provided by the Bureau of

NHI, Department of Health, and was managed by

the NHI Research Institutes in Taiwan. The interpretation and conclusions contained herein do not represent

those of the Bureau of NHI, Department of Health, or

National Health Research Institutes.

References

1. Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, Houghton LA,

Mearin F, Spiller RC. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology 2006;130:1480–91.

2. Lu CL, Chang FY, Chen CY, Luo JC, Lee SD. Significance of

Rome II-defined functional constipation in Taiwan and comparison with constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome.

Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2006;24:429–38.

3. Peppas G, Alexiou VG, Mourtzoukou E, Falagas ME. Epidemiology of constipation in Europe and Oceania: a systematic

review. BMC Gastroenterol 2008;8:5.

4. Johanson JF. Review of the treatment options for chronic constipation. Medgenmed [Computer file]. MedGenMed 2007;9:25.

5. Bharucha AE. Constipation. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol

2007;21:709–31.

6. Chen FP, Chen TJ, Kung YY, Chen YC, Chou LF, Chen FJ,

Hwang SJ. Use frequency of traditional Chinese medicine in

Taiwan. BMC Health Serv Res 2007;7:26.

7. Cheng SH, Chiang TL. The effect of universal health insurance

on health care utilization in Taiwan: results from a natural experiment. JAMA 1997;278:89–93.

8. Bureau of National Health Insurance, Department of Health,

Executive Yuan, R.O.C. Available at: http://www.nhi.gov.tw/

webdata/webdata.asp?menu=1&menu_id=4&webdata_id=

1399&WD_ID= [Date accessed: August 10, 2005]

381

M.S. Jong, et al

9. Berry MJ, Linoff G. Data Mining Techniques: For Marketing

Sales, and Customer Support. New York: Welly Press, 1997.

10. Han J, Kamber M. Data Mining: Concepts and Techniques. San

Francisco: Morgan Kaufmann Press, 2001.

11. Chen TJ, Chou LF, Hwang SJ. Application of a data-mining

technique to analyze coprescription patterns for antacids in

Taiwan. Clin Ther 2003;25:2453–63.

12. Chiarelli P, Brown W, McElduff P. Constipation in Australian

women: prevalence and associated factors. Int Urogynecol J 2000;

11:71–8.

13. Higgins PD, Johanson JF. Epidemiology of constipation in

North America: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol 2004;

99:750–9.

14. Xiao P, He L, Wang L. Ethnopharmacologic study of Chinese

rhubarb. J Ethnopharmacol 1984;10:275–93.

15. Ewe K. The physiological basis of laxative action. Pharmacology

1980;20(Suppl):2–20.

16. Heizer WD, Sandler RS, Seal E Jr, Murray SC, Busby MG,

Schliebe BG, Pusek SN. Intestinal effects of sulfate in drinking

water on normal human subjects. Dig Dis Sci 1997;42:

1055–61.

17. Tsai JC, Tsai S, Chang WC. Comparison of two Chinese medical

herbs, Huangbai and Qianniuzi, on influence of short circuit

current across the rat intestinal epithelia. J Ethnopharmacol 2004;

93:21–5.

18. Gilani AH, Aziz N, Ali SM, Saeed M. Pharmacological basis

for the use of peach leaves in constipation. J Ethnopharmacol

2000;73:87–93.

19. Xie DP, Chen LB, Liu CY, Zhang CL, Liu KJ, Wang PS.

Arecoline excites the colonic smooth muscle motility via M3

receptor in rabbits. Chin J Physiol 2004;47:89–94.

20. Deng S, Chen SN, Yao P, Nikolic D, van Breemen RB, Bolton

JL, Fong HH, et al. Serotonergic activity-guided phytochemical investigation of the roots of Angelica sinensis. J Nat Prod

2006;69:536–41.

21. Galligan JJ, Vanner S. Basic and clinical pharmacology of new

motility promoting agents. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2005;17:

643–53.

22. Tian YY, An LJ, Jiang L, Duan YL, Chen J, Jiang B. Catalpol

protects dopaminergic neurons from LPS-induced neurotoxicity

in mesencephalic neuron-glia cultures. Life Sci 2006;80:193–9.

23. Tundis R, Loizzo MR, Menichini F, Statti GA, Menichini F.

Biological and pharmacological activities of iridoids: recent

developments. Mini Rev Med Chem 2008;8:399–420.

24. Yamauchi K, Fujimoto N, Kuwano S, Inouye H, Inoue K. The

mechanism of purgative action of geniposide, an iridoid glucoside of the fruit of Gardenia, in mice. Planta Med 1976;30:

39–47.

25. Mehendale S, Aung H, Wang CZ, Tong R, Foo A, Xie JT, Yuan

CS. Scutellaria baicalensis and a constituent flavonoid, baicalein,

attenuate ritonavir-induced gastrointestinal side-effects. J Pharm

Pharmacol 2007;59:1567–72.

26. Yamahara J, Huang QR, Li YH, Xu L, Fujimura H.

Gastrointestinal motility enhancing effect of ginger and its active

constituents. Chem Pharm Bull 1990;38:430–1.

27. Huang YL, Yen GC, Sheu F, Chau CF. Effects of water-soluble

carbohydrate concentrate from Chinese jujube on different intestinal and fecal indices. J Agric Food Chem 2008;56:1734–9.

28. Capasso R, Borrelli F, Aviello G, Romano B, Scalisi C, Capasso F,

Izzo AA. Cannabidiol, extracted from Cannabis sativa, selectively

inhibits inflammatory hypermotility in mice. Br J Pharmacol

2008;154:1001–8.

29. De Filippis D, Iuvone T, D’Amico A, Esposito G, Steardo L,

Herman AG, Pelckmans PA, et al. Effect of cannabidiol on

382

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

43.

44.

45.

46.

47.

sepsis-induced motility disturbances in mice: involvement of

CB(1) receptors and fatty acid amide hydrolase. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2008;20:919–27.

Uddin SJ, Mondal K, Shilpi JA, Rahman MT. Antidiarrhoeal

activity of Cyperus rotundus. Fitoterapia 2006;77:134–6.

Sato Y, Akao T, He JX, Nojima H, Kuraishi Y, Morota T, Asano

T, et al. Glycycoumarin from Glycyrrhizae Radix acts as a potent

antispasmodic through inhibition of phosphodiesterase 3.

J Ethnopharmacol 2006;105:409–14.

Chan SS, Zhao M, Lao L, Fong HH, Che CT. Magnolol and

honokiol account for the anti-spasmodic effect of Magnolia officinalis in isolated guinea pig ileum. Planta Med 2008;74:381–4.

Grigoleit HG, Grigoleit P. Gastrointestinal clinical pharmacology

of peppermint oil. Phytomedicine 2005;12:607–11.

Yang HO, Ko WK, Kim JY, Ro HS. Paeoniflorin: an antihyperlipidemic agent from Paeonia lactiflora. Fitoterapia 2004;75:45–9.

Quartero AO, Meineche-Schmidt V, Muris J, Rubin G, de Wit

N. Bulking agents, antispasmodic and antidepressant medication

for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;2:CD003460.

Gilani AH, Shah AJ, Yaeesh S. Presence of cholinergic and calcium antagonist constituents in Saussurea lappa explains its use

in constipation and spasm. Phytother Res 2007;21:541–4.

Chang Q, Zuo Z, Harrison F, Chow MS. Hawthorn. J Clin

Pharmacol 2002;42:605–12.

Akagiri S, Naito Y, Ichikawa H, Mizushima K, Takagi T, Handa

O, Kokura S, et al. Bofutsushosan, an oriental herbal medicine,

attenuates the weight gain of white adipose tissue and the

increased size of adipocytes associated with the increase in their

expression of uncoupling protein 1 in high-fat diet-fed male

KK/Ta mice. J Clin Biochem Nutr 2008;42:158–66.

Saegusa Y, Sugiyama A, Takahara A, Nagasawa Y, Hashimoto K.

Relationship between phosphodiesterase inhibition induced by

several Kampo medicines and smooth muscle relaxation of gastrointestinal tract tissues of rats. J Pharmacol Sci 2003;93:62–8.

Riedlinger JE, Tan PW, Lu W. Ping wei san, a Chinese medicine for gastrointestinal disorders. Ann Pharmacother 2001;

35:228–35.

Hatanaka N, Yamagishi T, Kamemura H, Nakazawa I, Hirano

Y, Hosaka K, Sanno K, et al. A case of hepatitis and pneumonitis caused by Bofutsusyo-san herbal medicine. Nihon Kokyuki

Gakkai Zasshi 2006;44:335–9. [In Japanese]

Ikegami F, Sumino M, Fujii Y, Akiba T, Satoh T. Pharmacology

and toxicology of Bupleurum root-containing Kampo medicines

in clinical use. Hum Exp Toxicol 2006;25:481–94.

Xie H, Morikawa T, Matsuda H, Nakamura S, Muraoka O,

Yoshikawa M. Monoterpene constituents from Cistanche tubulosa: chemical structures of kankanosides A-E and kankanol.

Chem Pharm Bull 2006;54:669–75.

Kase Y, Hayakawa T, Ishige A, Aburada M, Komatsu Y. The

effects of Hange-shashin-to on the content of prostaglandin E2

and water absorption in the large intestine of rats. Biol Pharm

Bull 1997;20:954–7.

Ai M, Yamaguchi T, Odaka T, Mitsuhashi K, Shishido T, Yan J,

Seza A, et al. Objective assessment of the antispasmodic effect

of shakuyaku-kanzo-to (TJ-68), a Chinese herbal medicine, on

the colonic wall by direct spraying during colonoscopy. World J

Gastroenterol 2006;12:760–4.

Chen FP, Chen FJ, Jong MS, Tsai HL, Wang JR, Hwang SJ.

Modern use of Chinese herbal formulae from Shang-Han Lun.

Chin Med J 2009;122:1889–94.

Cheng CW, Bian ZX, Wu TX. Systematic review of Chinese

herbal medicine for functional constipation. World J Gastroenterol

2009;15:4886–95.

J Chin Med Assoc • July 2010 • Vol 73 • No 7

Chinese herb use for constipation in Taiwan

Appendix I. Summary of the scientific and Chinese equivalents of herbs and names appearing in this article

Angelica sinensis

Areca catechu

Artemisia scoparia

Asparagus cochinchinensis

Atractylodes lancea

Atractylodes macrocephala

Bupleurum chinense

Cannabis sativa

Cinnamomum cassia

Citrus aurantium

Citrus reticulate

Cistanche tubulosa

Coptis chinensis

Crataegus pinnatifida

Curcuma phaeocaulis

Cyperus rotundus

Dendrobium nobile

Ephedra sinica

Eriobotrya japonica

Forsythia suspense

Gardenia jasminoides

Glycyrrhiza uralensis

Gypsum Fibrosum

Ipomoea nil

ᅝូ

ឳᄏ

౼ຫ

֚॰מ

፧ؠ

ؠػ

־ո

ெࣤ

᷾ኔʻླྀʼ

ॹʻຫʼؼ

ۚⳠፚ

႓ຑ

՞⛹

⌇ؠ

ଉॵ

فක

႓

ࣣᆺ

ຑ

՞ඹ

ز౻

فፏ

ׄ

Ligusticum chuanxiong

Magnolia officinalis

Mentha haplocalyx

Mirabilite (sodium sulfate decahydrate)

Notopterygium incisum

Ophiopogon japonicus

Paeonia lactiflora

Phellodendron amurense

Pinellia ternate

Platycladus orientalis

Platycodon grandiflorum

Prunus armeniaca

Prunus persica

Rehmannia glutinosa

Rheum palmatum

Saposhnikovia divaricata

Saussurea lappa

Schizonepeta tenuifolia

Scrophularia ningpoensis

Scutellaria baicalensis

Sparganium stoloniferum

Talcum

Zingiber officinale

Ziziphus jujuba

՟ᮺ

দڸ

ᜳ๛ᆺ

ߝ࿎

ु

ຽ॰מ

ߟᢐ

႓ਹ

ת

ਹո

ே

ޖո

ո

چ႓

Օ႓

ଅ

ֵଉ

౸ग़

خ

႓ᴗ

Կᆆ

ᄶف

س᜶

Օའ

Appendix II. Summary of the English (Hanyu Pinyin) and Chinese equivalents of formulae and names appearing in this article

An-zhong-san

Ban-xia-xie-xin-tang

Da-chai-hu-tang

Da-huang-mu-dan-pi-tang

Fang-feng-tong-sheng-san

Gan-lu-yin

Liu-wei-di-huang-wan

Ma-zi-ren-wan

Mu-xiang-bin-lang-wan

ڜխཋ

תើ֨ྏ

Օྏ

Օ႓߃կྏؼ

ଅຏᆣཋ

زႏ

ք࠺چ႓Մ

ոՄ

Ping-wei-san

Run-chang-tang

Run-chang-wan

San-huang-xie-xin-tang

Shao-yao-gan-cao-tang

Tao-ren-cheng-qi-tang

Xie-fu-zhu-yu-tang

Yi-zi-tang

ؓષཋ

ᑮᆩྏ

ᑮᆩՄ

Կ႓ើ֨ྏ

ߟᢐز౻ྏ

ոʻுʼࢭྏ

ۨࢌດᅟྏ

Ԭྏڗ

ֵଉឳᄏՄ

J Chin Med Assoc • July 2010 • Vol 73 • No 7

383

© Copyright 2025