t he treatment

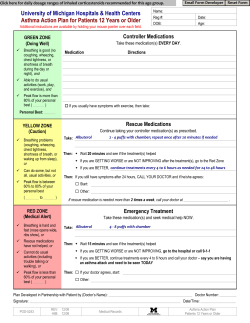

The treatment of acute asthma in children Sharon Kling, MB ChB, DCH (SA), FCPaed (SA), MMed(Paed), M Phil (Applied Ethics) Pierre Goussard, MB ChB, MMed(Paed) Robert P Gie, MB ChB, MMed(Paed), FCPaed (SA) Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, Tygerberg Children’s Hospital and Stellenbosch University, Tygerberg, South Africa ABSTRACT Despite advances in the understanding and management of asthma, children continue to present to health care institutions with acute asthma exacerbations. An accurate assessment of the severity of the acute attack is essential to ensure optimal treatment. The cornerstones of acute asthma treatment remain inhaled short-acting β2-agonists (SABA), oral corticosteroids, and oxygen. The inhaled therapy may be administered by means of an oxygen- or air-driven nebuliser, but the pressurised metereddose inhaler-spacer combination is preferable under certain circumstances. Inhaled ipratropium bromide should be added to the nebulised SABA in the event of a poor response to treatment. Other therapeutic options for non-responders are intravenous magnesium sulphate and intravenous salbutamol. INITIAL MANAGEMENT OF ACUTE ASTHMA IN CHILDREN The foundations of the treatment of acute asthma are bronchodilators, corticosteroids and oxygen. Inhaled β2-agonists constitute first-line therapy in acute asthma. Treatment with an inhaled short-acting β2-agonist (SABA) bronchodilator should be started as early as possible.4 The bronchodilator may be given by means of an oxygen- or air-driven nebuliser or with a metered-dose inhaler (MDI) and spacer combination.5 The SABA should be given as 3 doses 20 minutes apart, and the patient assessed for a response. Systemic corticosteroids (CS) should be administered early in the acute exacerbation. The oral route is the preferred route of administration of CS. The doses of SABA and CS are given in Table II. Poor response to initial therapy for acute asthma If there is an inadequate response to the above therapy after an hour, add nebulised ipratropium bromide (IB) every 20 minutes for the first 2 hours and 4-hourly thereafter.6 ISSUES RELATED TO INITIAL MANAGEMENT OF ACUTE ASTHMA Oxygen INTRODUCTION Great advances in our understanding and management of asthma have been made during the past two decades. Despite this and the improved use of controller medication, asthma exacerbations continue to pose a dilemma for paediatricians. Martinez1 points out that asthma exacerbations are a major component of asthma morbidity in both preschool and school-aged children, and that exacerbations occur despite adherence to adequate doses of controller therapy. Asthma is defined as a disease with variable airway inflammation and airflow obstruction. Asthma exacerbations are defined as ‘acute or subacute episodes of progressively worsening shortness of breath, cough, wheezing, and chest tightness – or some combination of these symptoms.’2 The pathophysiology of an asthma exacerbation includes airway oedema, mucus secretion and smooth-muscle spasm (bronchospasm). ASSESSMENT OF SEVERITY OF AN ACUTE ATTACK OF ASTHMA It is essential to assess the severity of an acute attack of asthma so that appropriate management can be instituted. The signs that should be assessed are pulse rate, respiratory rate, amount of breathlessness (ability to talk and feed), use of accessory muscles of respiration, extent and loudness of wheezing (which becomes less audible with increasingly severe airways obstruction), level of consciousness and presence of agitation (suggesting hypoxaemia). Table I details the features used in the assessment of severity of an acute attack.3,4 All children who have life-threatening asthma (Table I) or those with oxygen saturations <94% should receive high-flow oxygen via a mask or nasal-prong oxygen to obtain saturations ≥95%.4 Inhaled β2-agonists As previously stated, inhaled SABA may be given either by means of a nebuliser or with an MDI-spacer combination. Studies suggest that the MDI-spacer combination is more efficacious as well as more cost-effective than the nebuliser,5 provided that the patient is not acutely dyspnoeic.7 There is also evidence that children who receive the SABA via the MDI-spacer combination have fewer side-effects such as tachycardia and are less prone to hypoxia than when being nebulised.8 Homemade spacers such as the 500 ml cooldrink bottle are as efficacious as the commercially designed spacers.9 Children younger than 3 years of age will require a spacer which has a mask attached to the mouthpiece. For mild-moderate acute asthma attacks, 4-6 puffs of a SABA actuated into the spacer may be sufficient, but up to 10 puffs may be required for more severe asthma attacks. The puffs should not be actuated all at once, but at intervals of about 10 seconds between puffs, and 5 breaths of tidal breathing should follow each actuation. If the acute asthma attack is severe or life-threatening, the SABA should be administered at intervals of 2030 minutes by means of an oxygen-driven nebuliser. There is no advantage to giving continuous nebulised β2-agonists outside the intensive care unit (ICU); IB should be added if there is a poor response to the initial doses of β2-agonists. Correspondence: Dr Sharon Kling, Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, Faculty of Health Sciences, Stellenbosch University, PO Box 19063, Tygerberg 7505. Tel +27-21-938-9506, fax +27-21-938-9138, e-mail sk@sun.ac.za 22 Current Allergy & Clinical Immunology, March 2011 Vol 24, No. 1 Table I. Assessment of severity of acute asthma* Any one of the following in a child with severe asthma: Clinical signs Measurements Life-threatening asthma • Silent chest • SpO2 <92% • Cyanosis • PEFR <33% best or predicted • Poor respiratory effort • Hypotension, bradycardia • Exhaustion • Confusion or drowsiness Acute severe asthma • Unable to complete sentences in one breath; too breathless to talk or feed • Agitation • Accessory muscle use • P ulse rate >140/min in children 2-5 years old; >125/min in children >5 years old • R espiration >40 breaths/min in children 2-5 years old; >30 breaths/min in children >5 years old Moderate asthma • Able to talk in sentences exacerbation • Pulse rate ≤140/min in children 2-5 years old; ≤125/min in children >5 years old • SpO2 <92% • PEFR 33-50% • SpO2 ≥92% • PEFR ≥50% best or predicted • Respiration ≤40 breaths/min in children 2-5 years old; ≤30 breaths/min in children >5 years old SpO2 – oxygen saturation; PEFR – peak expiratory flow rate *Adapted from Davies et al.3 and the British Guideline on the Management of Asthma.4 Formoterol is a long-acting β2-agonist with a rapid onset of action, and it could therefore be used in the acute attack of asthma. A recent systematic review of nine trials concluded that formoterol may be used in the treatment of acute asthma in the setting of the emergency department.10 Steroid therapy If systemic steroids are used early on in the emergency department, the need for admission to hospital is reduced.11 Steroids have an onset of action of approximately 3-4 hours. The oral and intravenous routes have similar efficacy and onset of action, so the oral route is the preferred route of administration of CS.12,13 Intravenous therapy is only indicated in the child with very severe acute asthma who is vomiting or is too ill to take oral medication. The steroids should be given for approximately 3 days, but the length of the course does depend on the child’s condition and how long it takes for the child to recover from the acute attack of asthma. It is unnecessary to taper the dose of steroids unless the steroid course is longer than 2 weeks.4 Regarding inhaled steroids (ICS), their usual role is in the maintenance therapy of chronic asthma. ICS may improve airflow in acute asthma, with a more rapid onset than systemic steroids if administered in very high doses (approximately 5 times those given for maintenance therapy, in 2-3 divided doses, at varying intervals). The biggest disadvantage is the cost of the ICS compared to prednisone.14 There is currently insufficient evidence to recommend the use of ICS in acute asthma. It is, however, important that maintenance doses of ICS should be continued or started as soon as possible to form the basis of the child’s chronic asthma management plan.4 Ipratropium bromide (IB) The combination of the nebulised anticholinergic, IB, with a nebulised β2-agonist has been shown to result in greater bronchodilatation than a β2-agonist alone.6 The most severely affected patients benefit the most, and IB should be considered in combination with inhaled β2- agonists in the more severe forms of asthma, especially early in the acute attack, or if there is an incomplete response to inhaled β2-agonists on their own. Initially IB should be mixed in the same nebuliser as the β2-agonist and administered every 20-30 minutes for the first few hours after admission. Thereafter the β2-agonist should be weaned to 1-2 hourly depending on the clinical response, and the IB should be weaned to 4-6 hourly or stopped.4 OTHER THERAPIES IN THE MANAGEMENT OF ACUTE ASTHMA Magnesium sulphate A single dose of IV magnesium sulphate has been shown to be safe and effective in those patients with acute severe asthma who have had a poor response to initial therapy. The response to magnesium appears to be best in patients who present with very severe illness.15 The dose is 25-50 mg/kg/dose (maximum 2 g) by slow IV infusion. Intravenous salbutamol The use of IV salbutamol (15 µg/kg over 10 minutes as a once-off dose) in the early management of acute severe asthma in children presenting to the emergency department has been shown to reduce the duration of the exacerbation and hasten the discharge from hospital of the children.16,17 In the ICU IV salbutamol by continuous infusion may be considered if inhaled therapy is ineffective or for severe refractory asthma. It must be done with continuous ECG monitoring and regular electrolyte measurement (low serum potassium is a side-effect of multiple doses of inhaled and IV salbutamol). The dose of salbutamol consists of a loading dose of 5 µg/kg/min for 1 hour, then 1-2 µg/kg/min IV as an infusion.18 Intravenous aminophylline Theophylline and its water-soluble salt aminophylline are methylxanthine derivatives that have largely fallen Current Allergy & Clinical Immunology, March 2011 Vol 24, No. 1 23 Table II. Acute asthma management: drug dosages Inhaled short-acting β2-agonists Dose Salbutamol nebuliser solution (5 mg/ml) <2 years: 2.5 mg (½ ml) + 3 ml normal saline >2 years: 5 mg (1 ml) + 3 ml normal saline Fenoterol nebuliser solution (1 mg/ml) <2 years: 0.5 mg (½ ml) + 3 ml normal saline >2 years: 1 mg (1 ml) + 3 ml normal saline MDI + spacer (mask in children <3 years) 2-10 puffs, depending on severity of acute attack, each inhaled separately Corticosteroids Prednisone or prednisolone, oral 1-2 mg/kg/day, maximum dose 40 mg/day. Give for 3-5 days. No need for tapering Hydrocortisone 4 mg/kg 4-6 hourly IV Methylprednisolone 1-2 mg/kg 6 hourly IV Dexamethasone 0.15 mg/kg 6 hourly IV Anticholinergics Ipratropium bromide nebuliser solution 0.25 mg/ml; UDV 0.25 mg and 0.5 mg Add to short-acting β2-agonist nebuliser solution for first 1-2 hours, then wean to 4-6 hourly <2 years: 0.125 mg (½ ml) + 3 ml normal saline >2 years: 0.25 mg (1 ml) + 3 ml normal saline Intravenous salbutamol as single dose for severe asthma in emergency room 15 µg/kg as infusion over 10-15 minutes MDI – metered-dose inhaler, UDV – unit dose vial add-on therapy at presentation improved mean peak expiratory flow rates compared to placebo,25 and intravenous montelukast added to standard care in adults with acute asthma improved airway obstruction as measured by FEV1.26 Adrenaline Adrenaline 0.01 ml/kg of a 1:1000 solution administered subcutaneously may be used in patients who are moribund on presentation to the ED, or where inhaled therapy is not available. Intravenous fluids in acute asthma Patients with prolonged severe asthma may become dehydrated as a result of poor intake or vomiting. It is, however, inadvisable to overhydrate patients with acute asthma, and the recommended IV fluid volume in children should not exceed 50 ml/kg/24 hours. out of favour because of their narrow therapeutic index and potentially severe side-effects (cardiac arrhythmias, convulsions). Aminophylline is not indicated in patients with mild to moderate acute asthma, but it may be used in cases of near-fatal or life-threatening asthma in the ICU under continuous ECG monitoring.4 The loading dose is 6 mg/kg IV, then 0.5-1 mg/kg/hour by IV infusion; levels should be carefully monitored. Two studies have compared IV salbutamol and aminophylline.19,20 One study19 showed equivalent results, while the other demonstrated a shorter inpatient stay in the aminophylline group, but this group received a bolus plus infusion while the salbutamol group only received a bolus dose.20 There is insufficient evidence to either support or refute the use of antibiotics in acute asthma, but it is known that the majority of acute asthma attacks are precipitated by viral infections. Antibiotics should therefore not be given routinely.4 There is no evidence to support the use of heliox27 or mucolytics in children with acute asthma. Nebulised magnesium sulphate (on its own or with nebulised salbutamol) has shown some promise in respect of improved lung function in patients with severe asthma,28 but cannot currently be recommended for the routine treatment of acute asthma.4,28 Leukotriene receptor antagonists (LTAs) ICU INDICATIONS AND MANAGEMENT There is no clear evidence that oral LTAs have a role in the management of moderate to severe acute asthma exacerbations in children older than 2 years of age, although they do decrease symptoms, hospitalisations and steroid use in the primary care setting.4,21-24 A recent adult study suggested that oral montelukast as Table III. Indications for admission to intensive care unit Poor response to maximal pharmacological therapy in ward/emergency room Unproven therapies The indications for admission to ICU are detailed in Table III. Continuous nebuliser therapy with β2-agonists may be more effective than intermittent therapy in the setting of severe acute asthma.29 Some of the therapies used in the intensive care setting are detailed above (IV salbutamol and aminophylline). The discussion of mechanical ventilation and adjunctive intensive care therapies are beyond the scope of this article, and have been discussed in detail by Prof Tex Kissoon in Current Allergy & Clinical Immunology in August 2007.30 Figure 1 summarises the management plan for hospital treatment of children with acute asthma. Cyanosis and hypoxaemia (PaO2 <8kPa) unrelieved by O2 HOSPITAL DISCHARGE AND FOLLOW UP PaCO2 >4.5kPa It is difficult to define when patients can safely be discharged after being admitted with acute asthma. They should certainly be on treatment that they could manage at home, and be receiving minimal inhaled β2agonists. They should receive asthma education with emphasis placed on treatment and inhaler technique. They should be discharged on appropriate maintenance therapy, with a written action plan to manage exacerbations. They should have a follow-up appointment with their primary care provider within a week of discharge. PEFR <30% predicted or best Minimal chest movement, ‘silent’ chest Severe retraction Deteriorating mental status, lethargy or agitation Cardiorespiratory arrest aO2 – oxygen partial pressure; PaCO2 – carbon dioxide partial P pressure, PEFR – peak expiratory flow rate. 24 Current Allergy & Clinical Immunology, March 2011 Vol 24, No. 1 MANAGEMENT OF ACUTE SEVERE ASTHMA IN HOSPITAL Initial assessment DANGER SIGNS History, examination, oxygen saturation (SpO2), Cyanosis; SpO2 <92% peak expiratory flow (PEF) Previous ICU admission Acute episode >12 hours Recent oral steroids Drowsy or confused Silent chest on auscultation Initial treatment O2 Initiate therapy with O2, Inhaled short-acting β2-agonist (SABA) (nebuliser or MDI/spacer) 1 dose every 20 min x 1 hour inhaled SABA, oral steroids. Oral corticosteroid If no response Good response* Incomplete/poor response** Observe x 1 hour Add ipratropium bromide (IB) 4 hourly If stable, discharge Good response* Respiratory failure Poor response** Follow-up plan Discharge Admit to hospital Follow-up plan Continue O2, nebulised SABA+IB, oral corticosteroids Other options IV magnesium sulphate IV salbutamol (once-off dose) Admit to ICU IV magnesium sulphate Continue nebulised SABA+IB IV corticosteroids IV salbutamol and/or aminophylline infusions Intubation and ventilation *Good response • Not tachypnoeic • Minimal wheezing • No retraction • Able to speak and feed (young child) • PEF ≥80% predicted or personal best **Incomplete/poor response • Tachypnoeic • Persistent wheezing • Retraction present • Impaired speech or feeding • PEF ≤79% predicted or personal best Fig. 1. Management of acute asthma in hospital – adapted from Kling et al.31 (with permission of the editors). Declaration of conflict of interests SK & PG have given talks for MSD and GSK; SK was sponsored to the 2010 ALLSA Congress by Cipla Medpro; RPG declares no conflict of interest in respect of the contents of this article. REFERENCES 1.Martinez FD. Managing childhood asthma: challenge of preventing exacerbations. Pediatrics 2009; 123: S146-S150. 2.Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention 2009 (Update) www.ginasthma.org. Accessed 23 February 2010. 3.Davies G, Paton JY, Beaton SJ, et al. Children admitted with acute wheeze/asthma during November 1998-2005: a national UK audit. Arch Dis Child 2008; 93: 952-958. 4.The British Thoracic Society Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. The British Guideline on the Management of Asthma. May 2008, revised June 2009. www.brit-thoracic.org.uk. Accessed 23 January 2011. Current Allergy & Clinical Immunology, March 2011 Vol 24, No. 1 25 5.Schuh S, Johnson DW, Stephens D, et al. Comparison of albuterol delivered by metered dose inhaler with spacer versus a nebuliser in children with mild acute asthma. J Pediatr 1999; 135: 22-27. 6.Plotnick LH, Ducharme FM. Acute asthma in children and adolescents: should inhaled anticholinergics be added to beta 2-agonists? Am J Respir Med 2003; 2(2): 109-115. 7.Lugogo NL, MacIntyre NR. Life-threatening asthma: pathophysiology and management. Respir Care 2008; 53: 726-735. 8.Cates CJ, Rowe BH, Bara A, et al. Holding chambers (spacers) versus nebulisers for beta-agonist treatment of acute asthma. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2006, Issue 2. Art No CD000052. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000052.pub2. 9.Zar HJ, Brown G, Donson H, et al. Home-made spacers for bronchodilator therapy in children with acute asthma: a randomised trial. Lancet 1999; 354:979-982. 10.Rodrigo GJ, Neffen H, Colodenco FD, Castro-Rodriguez JA. Formoterol for acute asthma in the emergency department: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2010; 104: 247-252. 11.Rowe BH, Spooner C, Ducharme FM, et al. Early emergency department treatment of acute asthma with systemic corticosteroids. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2001, Issue 1. Art No CD002178. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002178.pub1. 12.Manser R, Reid D, Abramson M. Corticosteroids for acute severe asthma in hospitalised patients. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2001, Issue 1. Art No CD001740. DOI: 10.1002/14651858. CD001740.pub1. 13.Becker JM, Arora A, Scarfone RJ, et al. Oral versus intravenous corticosteroids in children hospitalized with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1999; 103: 586-590. 14.Volovitz B. Inhaled budesonide in the management of acute worsening and exacerbations of asthma: a review of the evidence. Respir Med 2007; 101: 685-695. 15.Silverman R. Treatment of acute asthma. Clin Chest Med 2000; 21: 361-379. 16.Browne GJ, Penna AS, Phung X, Soo M. Randomised trial of intravenous salbutamol in early management of acute severe asthma in children. Lancet 1997; 349: 301-305. 17.Browne GJ, Lam LT. Single-dose intravenous salbutamol bolus for managing children with acute severe asthma in the emergency department: Reanalysis of data. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2002; 3: 117123. 18.Shann F. Drug Doses. 13th ed. Melbourne: Royal Children’s Hospital, 2005. 19.Wheeler DS, Jacobs BR, Kenreigh CA, et al. Theophylline versus terbutaline in treating critically ill children with status asthmaticus: a prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2005; 6: 142-147. 20.Roberts G, Newsom D, Gomez K, et al. Intravenous salbutamol bolus compared with an aminophylline infusion in children with severe asthma: a randomised controlled trial. Thorax 2003; 58: 306-310. 21.Harmanci K, Bakirtas MD, Turktas I, et al. Oral montelukast treatment of pre-school-aged children with acute asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2006; 96: 731-735. 22.Robertson C, Proce D, Henry R, et al. Short-course montelukast for intermittent asthma in children: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007; 175: 323-329. 23.Nelson KA, Smith SR, Trinkaus K, et al. Pilot study of oral montelukast added to standard therapy for acute asthma exacerbations in children aged 6 to 14 years. Pediatr Emerg Care 2008; 24: 21-27. 24.Capsomidis A, Tighe M. Archimedes. Question 2. Is oral montelukast beneficial in treating acute asthma exacerbations in children? Arch Dis Child 2010; 95: 948-950. 25.Ramsay CF, Pearson D, Mildenhall S, Wilson AM. Oral montelukast in acute asthma exacerbations: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Thorax 2011; 66: 7-11. 26.Camargo CA, Gurner DM, Smithline HA, et al. A randomized placebo-controlled study of intravenous montelukast for the treatment of acute asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2010; 125: 374-380. 27.Rodrigo GJ, Pollack CV, Rodrigo C, Rowe BH. Heliox for non-intubated acute asthma patients. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2006, Issue 4. Art No CD002884. DOI: 10.1002/14651858. CD002884.pub2. 28.Blitz M, Blitz S, Beasely R, et al. Inhaled magnesium sulphate in the treatment of acute asthma. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2005, Issue 4. Art No CD003898. DOI: 10.1002/14651858. CD003898.pub4. 29.Camargo CA, Spooner C, Rowe BH. Continuous versus intermittent beta-agonists for acute asthma. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2003, Issue 4. Art No CD001115. DOI: 10.1002/14651858. CD001115.pub4 30.Kissoon N. The child with asthma – emergency and critical care issues. Current Allergy & Clinical Immunology 2007; 20: 116-122. 31.Kling S, Goussard P, Gie RP. Chapter 5. Management of asthma exacerbations and acute severe asthma. In: Green RJ, Motala C, Potter PC, eds. ALLSA Handbook of Practical Allergy, 3rd ed. Paarl: ALLSA, 2010. First Announcement $GYDQFHVLQ 3DHGLDWULFV$OOHUJ\ Joint Meeting ALLSA & PMG Congress 2011 20 - 23 October • Sun City • South Africa Provisional Programme • • • • • • • • • New concepts in food allergy Understanding wheeze in young children Allergy management in the year 2011 Primary immunodeficiency workshop and a clinical approach to recurrent infections in children Feeding newborns to prevent disease Infectious diseases in children Practice management and coding Financial Management for Doctors Ethics Session Organising Committee Dr Andrew Halkas Dr Humphrey Lewis Dr Andre van Niekerk Congress Office Joint Meeting ALLSA & PMG Congress 2011 T+27 011 447 3876 F +27 011 442 8094 suemc@icon.co.za www.allergysa.org

© Copyright 2025