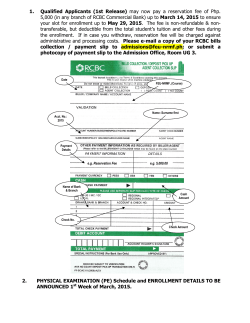

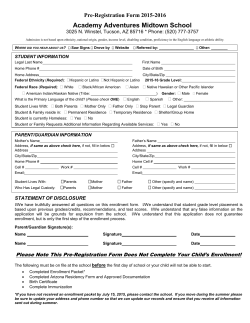

School Fees and Access to Primary Education: Assessing Four