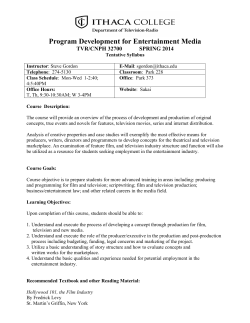

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, DOMINGUEZ HILLS SONS OF RESEARCH CONDUCTED BY: LEAH HOLLAR

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, DOMINGUEZ HILLS PORTRAYALS OF THE ANTITHESIS OF HEGEMONIC FEMININITY ON SONS OF ANARCHY RESEARCH CONDUCTED BY: LEAH HOLLAR A RESEARCH PAPER SUBMITTED TO DR. SHARON SHARP TO SATISFY THE REQUIREMENT FOR COMMUNICATIONS 490 CARSON, CA DECEMBER 6, 2012 Introduction Female characters on television have come a long way since the days of June Cleaver, the doting housewife on Leave it to Beaver. The mild-mannered women who ruled the domestic space on television in the past have been replaced with gun-toting, promiscuous, over-emotional women who are criminals, single mothers, powerful professionals, and lesbians. Whether these female characters are represented as over-emotional, women who fail at love on reality shows like The Bachelor, or an androgynous lesbian on Showtime’s The L Word, women on television are increasingly portrayed as the antithesis of hegemonic femininity. At the end of her work titled Postfeminist Television Criticism: Rehabilitating Critical Terms and Identifying Postfeminist Attributes, Amanda Lotz calls for feminist media scholarship that “must adopt new ways to identify and explore textual developments as theorists recognize new ways of understanding relations of power and gender circulating in societies, and the women living in those societies redefine their concerns and priorities” (117). Examining this new breed of female characters is important in the discourse of feminist media studies. By studying these subjects of popular culture we are able to better understand our own societal and cultural concerns and priorities. Sons of Anarchy is the most-watched series on the FX network. The show earned record ratings for the network with it’s fifth season premier episode. Actress Katey Sagal has received critical acclaim for her role, even winning a Golden Globe for “Best Actress in a 2 Television Drama Series” in 2011. By analyzing the female lead character on a quality television series, Gemma Teller Morrow (Katey Sagal) on Sons of Anarchy, I will show how she portrays the antithesis of hegemonic femininity. My analysis will draw from feminist media studies, gender studies, and quality television studies. Literature Review Quality Television Quality television is a rather broad genre with many sub genres that fall into it. Some characteristics of this genre include “reliance on an ensemble cast, its deployment of multiple overlapping plot lines, its social and cultural commentary, and its combination of old genres to create new ones” (Thompson 12-16). High quality production and filming, along with a creative aural style also mark the genre. A look at contemporary American quality programming is explained by Janet Akass and Kim McCabe as tending to exhibit, “naturalistic performance styles, recognized and esteemed actors, a sense of visual style created through careful, even innovative, camerawork and editing, and a sense of aural style created through the judicious use of appropriate, even original music” (26). A higher level of engagement on the part of the quality television viewer sets this genre apart from its competition. Complex narrative, storytelling, and relationships - rather than a focus on the mundane and trivial, are pursued. (Akass, McCabe, 26-27). Quality television stands out as a unique genre not 3 only because of its industrial and technical features but also due to its cultural and societal implications. Aniko Imre, writing on gender and quality television said, “The global dispersion of quality programs underscores the need for feminist translations in the face of recent industrial and scholarly efforts to remasculinize television by emphasizing aesthetic value at the expense of television’s ideological aspects” (Imre, 393). Her call for feminist translations of quality television emphasizes the genre’s deeper ideologies, which are often explored. Quality television is more prevalent on cable and premium channels like HBO and Showtime but has expanded as programming demands have risen and production values are increased. The philosophies behind the programs of the genre focus on something deeper than purely “violence for violence sake.” Gender Hegemony In order to argue that Gemma Teller Morrow is the antithesis of the hegemonic ideal of femininity, it is important to explain the theory on gender hegemony. Prior to sociologist Mimi Schippers’ book Recovering the Feminine Other: Masculinity, Femininity, and Gender Hegemony, a theory for hegemonic femininity had not yet been defined in gender studies. In her book, Schippers uses R.W. Connell’s conceptualization of gender hegemony to provide a clear understanding and theory of hegemonic femininity, stating that, “Hegemonic femininity consists of the characteristics defined as womanly that establish and legitimate a hierarchical and complementary relationship to hegemonic 4 masculinity and that, by doing so, guarantee the dominant position of men and the subordination of women” (94). Connell lays out womanly virtues as including, “compliance, nurturance, and empathy” (Connell, 188). Schippers also draws on Connell’s theories of hegemonic gender relations as they relate to women who engage in hegemonic masculinity. Women who engage in such behavior as promiscuity and aggressiveness are stigmatized and faced with social sanctions. Their refusal to accept the role of femininity laid out by society threatens men’s exclusive possession of hegemonic masculine characteristics (Schippers, 95). Women who engage in hegemonic masculinity are seen as a threat to the traditional gender binaries. Whether on television or in real life, these stigmatized women are seen as threatening to men because they hold the power of masculine characteristics. Kerry Fine, in her study of female western heroic characters who subvert the gender binary, describes Gemma Teller Morrow as a woman who takes “an active role in pursuing her own justice” (158). By placing female characters in roles traditionally reserved for men of power, the “socially constructed terms of who is permitted to exercise that power are redefined” (153). “Gemma does not neatly fit into the valuehierarchical structure into which the other women are relegated. So while the series in general reinforces the gender binary and traditional gender performances, Gemma’s character resists the simple classification as feminine” (Fine, 164). With Gemma wielding the power, she is placed outside the gender binary, and therefore becomes the antithesis of hegemonic femininity. 5 Feminist Media Studies In order to understand hegemonic femininity and issues of femininity, it helps to look into the many feminist media studies that exist. Going back to Amanda Lotz’s criticism of postfeminist television, she calls for a deeper understanding of characters without quickly dismissing them as part of the hegemonic system. Lotz says: Feminist theory is beginning to offer tools for understanding the complexity of living feminism in a world full of tangled issues and priorities for women with many different opportunities and privileges. Examining the intricacy of these images provides a much more productive route for feminist media criticism than simple categorization of new characters and series as anti-feminist because of character flaws or moments of conservative ideology. Especially when series and characters resonate with audiences to the degree that many recently have, we must explore what is in these texts with an eye to their complexity instead of quickly dismissing them as part of a hegemonic, patriarchal, capitalist system. (114) Lotz highlights the need for in-depth analysis, rather than simply categorizing characters or series. By focusing on the complexity of the texts, we acknowledge that dismissing them as belonging (or not belonging) to the hegemonic system leaves room for further discourse. In discussing femininity and its role in feminist media studies, Belinda Stillion Southard 6 uses Sex and the City as an example of feminist struggles. She writes, “What is meant by ‘feminine’ is integral to understanding how femininity differs from and intersects with what is considered ‘feminist.’ Historically, femininity is a traditional and accessible means of assessing a woman’s worth as defined by men and is often associated with domesticity” (157). Femininity, then, can be an ideal produced by men but what is considered ‘feminist’ is the ideals of scholars. Stillion Southard says that femininity and feminism can intersect, Television’s adaptation of feminism typically conflates feminism and femininity in that women cannot successfully represent both concepts without eclipsing one or the other. Additionally, these two concepts are constantly exchanged in that these characters exercise their feminist freedoms, but remain preoccupied with their attractiveness, or femininity. (Stillion Southard, 158) This modern portrayal of women who are concerned with feminist ideals but also with their femininity we’ve seen on shows from The Mary Tyler Moore Show to Sex and the City. Lynne Joyrich, in her book, Re-viewing Reception: Television, Gender, and Postmodern Culture, points out the importance of looking at masculinity when analyzing feminist issues. Joyrich says, While the figure of femininity has been quite productive...for cultural analysis, the figure of masculinity has recently become important for 7 feminist analysis. Critical of the way in which the concept of ‘sexual difference’ is simply projected onto women as the different sex...feminist theorists have interrogated the supposed unity of gender identity and attempted to dismantle the dualistic logic which underpins this assumption. (71) By placing women in roles of power on television, the subversion of femininity has enabled a strategy depicting an excess of ‘maleness’ and ‘hypermasculinity’ in popular culture. Joyrich says, A common strategy of much of television is to react against this feminine inscription through the construction of a violent hypermasculinity--an excess of ‘maleness’ that acts as a shield. In this way, television’s defense against the feminine may be seen as corresponding with television theory’s attempts to dispense with the same; by either resisting the feminine position (as many TV texts do) or else incorporating and hence speaking for it (as occurs in some recuperative critical texts), the real presence of women within both these particular televisual and critical discourses is deemed unnecessary. (79) This defense seems to create new female characters who resist the hegemonic ideals of femininity. An extended study of feminism can also help us understand woman and her role in 8 society. Kathleen Hall Jamieson, in her book, Beyond the Double Bind: Women and Leadership focuses on the many double binds that women face (ex: the uterus-brain bind —“you can’t conceive children and ideas at the same time”) and how they can overcome them. She says, “While a true woman culture may no longer be relevant, femininity is still defined by a key set behavioral and cosmetic virtues, that, if violated, automatically suggests a woman is either promiscuous or masculine” (1995). This definition of femininity, which plagues our society despite evolution in the feminist movement, is a good example of a dichotomy in gender hegemony. Many optimistic feminist theorists believe that women can, indeed, “have it all.” Aniko Imre reminds us we live in a “postfeminist” era. She says, “Thanks to earlier, successful feminist struggles for equal rights, women can now have both family and careers, and can live and love like men without giving up their femininity” (391). The evolution of women existing solely in the home to inhabiting both the office and the home has been an important progression in the feminist timeline, and can regularly be seen portrayed on television. Women are increasingly shown in positions of power, and even in masculine roles, while still maintaining their femininity. Long seen as an issue in feminist media studies is the ‘male gaze’. As Laura Mulvey says, “Women are regarded as objects of fetishistic display for male viewers’ pleasure” (4). Suzanna Danuta Walters, on the same topic, says women are also viewers, even if our representation is man-made. Feminist critics have been quick to point out that the representation of 9 women in this media-saturated society is particularly fraught with contradictions and dilemmas. For it is women who more often than not are the “imaged” in our culture...Yet women are in the strange and unique position of also being spectators, consumers of their very own image, their very own objectification. At the same time that we witness our own representation, we are also, so often, denied a place in that process of representation--denied a voice--so that more often than not those images of ourselves that stare at us from the glossy pages of the women’s magazines or from the glowing eye of the television screen are not of our own creation. They are, in more senses than one, truly “manmade.” (22-23) Women can be spectators of their own objectification, and can even relate to the representation at times, but the overwhelming creators of the female image are most commonly men. The problem with men being the creators and enforcers of the female stereotype is the hegemonic gender values they place on women. “In both popular culture and academic discourse, maleness remains a protected provenance for the cultivation of privileged forms of masculinity, while feminism becomes in both arenas a diluted discourse about women’s desires for domestic security, love, and family” (Gardiner, 347). We see this pattern of diluted discourse about women’s desires everywhere. A great example is Carrie Bradshaw (Sarah Jessica Parker) on Sex and the City who has financial independence and 10 her own career but ultimately wants a man in her life. Analysis Sons of Anarchy is considered to be a quality television show. It features an ensemble cast, which includes Ron Perlman and Katey Sagal, is structured with multiple overlapping plot lines, and combines elements of several classic genres to create a new hybrid. An update to the Western drama genre, Sons of Anarchy features a violent motorcycle gang that is busy in drug dealing, gun running, and sometimes the porn business. Created, written, produced, directed, and sometimes starring Kurt Sutter, the show features Sutter’s own creative, if viciously violent, aural style. Depictions of violence and sex always come at a karmic cost to the characters. Viewers remain engaged throughout complex narratives and revolving cast of characters. The show is set in the small, fictional town of Charming. The ruthless members of SAMCRO (Sons of Anarchy Motorcycle Club, Redwood Original) are constantly working to protect the small-town values of Charming against capitalist forces. As the matriarch of the SAMCRO motorcycle club, and the “old lady” of the club’s leader, Clay Morrow (Ron Perlman), Gemma occasionally shows her archetypal feminine qualities. Overall, however, her actions go against the conventional womanly virtues laid out by Connell. Gemma is increasingly noncompliant when it comes to the law, she commits adultery, drinks heavily and is violent. Gemma Teller Morrow becomes the antithesis of hegemonic femininity as the Sons of Anarchy series develops. 11 Her aggression, oftentimes used in order to protect herself, her family, or the motorcycle club, is carried out with a gun. Fine highlights Gemma’s use of a gun on the show, a trait that is traditionally the “symbol of male power” (158). In the finale of the second season, “Na Triobloidi” (FX12/1/2009) Gemma seeks revenge on the woman who helped in her capture and eventual rape. Gun drawn, she fires without hesitation and kills the woman. In the episode “Bainne” (FX 11/16/10) Gemma visits a black-market orphanage, where she believes her kidnapped grandson may be held. When the nuns running the orphanage refuse to divulge the whereabouts of the baby, Gemma grabs a baby from it’s cradle and threatens to kill it if the nuns don’t speak up. “While it may seem that her figuration as the protective (grand) mother might somehow feminize her aggression to be socially acceptable, the scene is arranged to make it clear that she is not acting on simple maternal instinct, a socially constructed gendered behavior in itself, but that she wields instrumental aggression in an unfeminine way” (Fine, 168). Her choice to threaten to kill a baby, rather than threaten to take the life of one of the adults in the room, shows Gemma’s general lack of instinct to protect and nurture. (Fine, 170). Gemma’s promiscuity becomes an issue after her marriage to Clay Morrow unravels at the end of the fourth season. The first episode of the fifth season opens with Gemma seen having sex with an unknown man. While the man becomes a prominent character later in the season, her actions prove reckless as she wakes up with no recollection of the previous night’s events. While she was not the first to commit adultery, (she catches her husband with another woman at the end of the fourth season) her actions are still seen as 12 unsavory. The fifth season marks her unraveling as she faces social sanctions for her behavior. Her son, Jax Teller, now the President of the SAMCRO motorcycle gang, becomes increasingly distant, and Jax’s wife won’t trust Gemma to baby-sit their children. The motorcycle club is its own society within a small town. A set of governing rules of the club are overseen by the club’s leader, while important decisions are voted on by all the male members of the club. The men make important decisions which occasionally come with deadly consequences that the women are forced to suffer. The misfortunes have included rape--in the case of Gemma, and the death of a husband--in the case of Opie Winston (Ryan Hurst) and Lyla Winston (Winter Ave Zoli). Similar to the way in which crime dramas have been criticized for portraying women as either “pros” or “prostitutes” (Nunn, Biressi, 93), Sons of Anarchy falls into casting their female characters in stark contrasts as professionals or sex objects. Gemma Teller Morrow is often seen working in the office on paperwork or emerging from her shiny black Cadillac SUV. Gemma’s daughter-in-law, Tara Knowles (Maggie Siff), is also portrayed as a “pro”. As a surgeon at a local hospital, Tara places a lot of importance on her career. The other women of the motorcycle club, such as Opie’s wife, Lyla, are porn actresses or faceless women who are commonly seen romping around the clubhouse halfnaked, being taken advantage of by the men. This fetishistic display of women benefits the male gaze and epitomizes the contrast of the “pros” or “prostitutes” phenomenon. As sexual objects, women who have not earned “old lady” status are referred to as “sweet 13 butt,” “crow eater,” or “gash.” These promiscuous women are treated as objects by the men and shunned by the club’s “old ladies.” Sons of Anarchy is a mostly “man-made” product, so the portrayal of women who exemplify hegemonic gender values is diminished. While Gemma Teller Morrow is not an average housewife, she still desires domestic security, love, and family. After finding out that her husband put a hit on her daughter-in-law, Gemma pulls a gun on Clay Morrow in the episode “Hands.” (FX 11/8/11) He beats her badly. From this point on, she does everything in her power to protect her son, going so far as to risk a new love by deceiving her former love. Katey Sagal, speaking with NPR about her role as Gemma said, “It was not so much the heinous things she does; it was that at her core, her motivation is her children, is her child. At any cost, she will protect him and her club." Gemma’s devotion to motherhood and loyalty to the club which serves as a family makes her more feminine despite her aggression actions. Gemma Teller Morrow is an overtly sexual alpha female amidst the manliest of men. Her refusal to accept the role of femininity laid out by society is a threat to man’s exclusive powers. The men in the motorcycle club see her as a mother figure - but it was her motherhood that made her the target of a sexual assault by a group attempting to gain power in Charming. Gemma was gang-raped in the beginning of season 2. The man behind the rape said in the episode “Small Tears,” (FX 10/15/2009) “unraveling the matriarch will destabilize them. They’re all little boys who need a strong mommy.” Rather than acting immediately on emotions, she decides to wait to tell anyone until she 14 is sure justice can be sought. Her toughness and calculation in seeking power makes her less feminine. Her power however has allowed her to survive throughout the show, without being killed off as a result of her gender transgressions. Conclusion Gemma Teller Morrow does not embody the womanly virtues as laid out by Connell. She engages in hegemonic masculinity with her aggressive and violent nature, and faces social sanctions for such actions. Gemma therefore does not fit the model of hegemonic femininity. While she, and many contemporary female television characters, does not fit into the value-hierarchical structure, she does broaden the markers of her gender. This new performance of the feminine alters the gender binary, if only on television. Her complexity allows viewers to engage with and analyze the text in a deeper way. Female characters like Gemma, who take on such complex roles that allow them to wield aggressive power while acting to protect loved ones, are important to the feminist media discourse. 15 Works Cited Connell, R.W. Gender and Power: Society, the Personal and Sexual Politics. Cambridge: Polity, 1987. Print. Fine, Kerry. "She Hits Like a Man, But She Kisses Like a Girl: TV Heroines, Femininity, Violence, and Intimacy." Western American Literature 47.2 (2012): 153-73. Project MUSE. Web. 12 Nov. 2012. Gardiner, Judith Kegan. Masculinity Studies & Feminist Theory : New Directions. n.p.: Columbia University Press, 2002. eBook Collection (EBSCOhost). Web. 25 Nov. 2012. Imre, Anikó. "Gender And Quality Television." Feminist Media Studies 9.4 (2009): 391- 407. Academic Search Premier. Web. 1 Oct. 2012. Jamieson, K.H. Beyond the double bind: Women and Leadership. New York: Oxford UP, 1995. Print. 16 Joyrich, Lynne. Re-viewing Reception: Television, Gender, and Postmodern Culture. Bloomington, IN: Indiana UP, 1996. Print. “Katey Sagal, Holding Court On ‘Sons of Anarchy’” Fresh Air. NPR. WHYY, Philadelphia, PA. 31 Oct. 2012. Radio. Transcipt. Lotz, Amanda D. "Postfeminist Television Criticism: Rehabilitating Critical Terms and Identifying Postfeminist Attributes." Feminist Media Studies 1.1 (2001): 105-21. Academic Search Premier. Web. 27 Nov. 2012. McCabe, Janet, and Kim Akass. Quality TV: Contemporary American Television and beyond. London: I.B. Tauris, 2007. Print. Mulvey, Laura. Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema. Germany: Grin Verlag, 1999. Print. Nunn, Heather, and Anita Biressi. "Silent Witness : Detection, Femininity, and the Post- mortem Body." Feminist Media Studies 3.2 (2003): 193-206. Web. 20 Nov. 2012. Schippers, Mimi. “Recovering the Feminine Other: Masculinity, Femininity and Gender Hegemony.” Theory and Society. 36 (2007): 85-102. Academic Search Premier. Web. 1 Oct. 2012 Thompson, Robert J. Television's Second Golden Age: From Hill Street Blues to ER : Hill Street Blues, St. Elsewhere, Cagney & Lacey, Moonlighting, L.A. Law, Thirtysomething, China Beach, Twin Peaks, Northern Exposure, Picket Fences, 17 with Brief Reflections on Homicide, NYPD Blue, Chicago Hope, and Other Quality Dramas. New York: Continuum, 1996. Web. Walters, Suzanna Danuta. Material Girls: Making Sense of Feminist Cultural Theory. Berkeley: University of California, 1995. Web. 18

© Copyright 2025