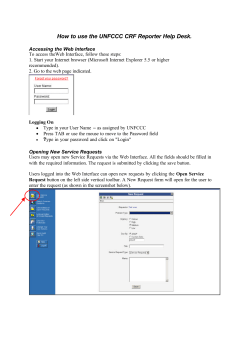

Assessment and Review under a 2015 Climate