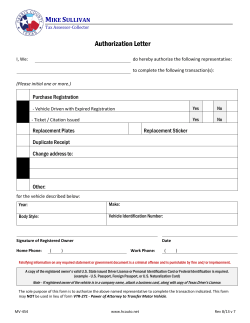

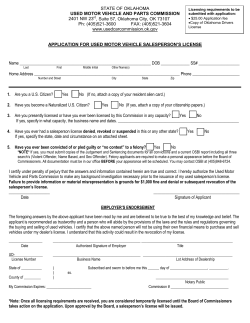

1