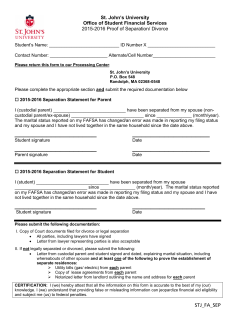

the Full Article