Volume 8 Issue 2 Year 2009 VHJOE Editor:

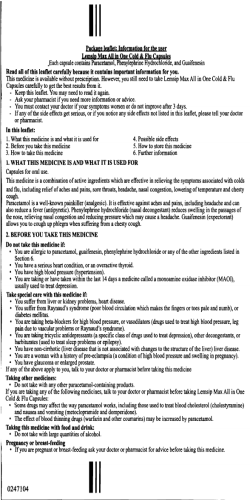

Vo l u m e 8 Issue 2 Ye a r 2 0 0 9 VHJOE Editor: John Deutsch, MD St. Mary’s Duluth Clinic International Editor: Manoop S. Bhutani, MD MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston TX Above: View of Interactive Atlas, showing selected anatomical structures (left) and corresponding oblique section (right). The Visible Human Journal of Endoscopy (VHJOE) is a PEER REVIEWED journal, featuring EMBEDDED VIDEO CLIPS and IMAGE-RICH articles. VHJOE publishes EXPERT REVIEWS from leading gastroenterologists as well as interesting CASE REPORTS. Additionally, VHJOE features the VISIBLE HUMAN INTERACTIVE ATLAS, a powerful, web-based application, developed by the Center for Human Simulation, which provides unparalleled views of human anatomy. Visit us online at www. vhjoe.org Editorial Board: William R. Brugge, MD Massachusetts General Hospital Peter R. McNally, DO Denver, CO Thomas J. Savides, MD University of California, San Diego C. Mel Wilcox, MD University of Alabama, Birmingham Visible Human Project® is a registered trademark of the U.S. National Library of Medicine. The National Library of Medicine is not affilated with the publication of this journal. Vo l u m e 8 Issue 2 Ye a r 2 0 0 9 Ta b l e o f Contents EDITORIAL Editorial: Non Steroidal Anti Inflammatory Agents in Gastroenterology John C. Deutsch, M.D.......................................................................................................1 ARTICLES NSAID Induced Small Bowel Strictures Managed by Combined Operative Endoscopy and Surgical Resection: A Case Report and 5 year Follow Up. P. Alexander McNally, BS; Lonnie L. Imlay, MD; Joseph Pineau, MD; Peter R. McNally, DO .................................................................2 Angioedema Presenting as Abdominal Pain With Vomiting. Ryan M Harden, MD, MS; John C Deutsch MD; Jay L Parker, DO.............................................................................................................6 C A P S U L E E N D O SCOPY NSAID Enteropathy and Capsule Retention; Complication or Guide to Therapy? Martin I. Radwin, M.D...................................................................................................9 TO P I C R E V I E W Topic Review: Clopidogrel and PPI Competition for CYP2C19: “Heart Attack or Heartburn?” Peter R. McNally, DO...................................................................................................13 CASES FROM THE ARMED FORCES INSTITUTE OF PATHOLOLOGY NSAID Ulcer Kathryn M. Johnson, CPT, MC, USA; Angela Levy, COL, MC, USA; Fidelina Desoto-Lapaix, MD; Leslie H. Sobin, MD......................................................................................................15 Visit us online at www. vhjoe.org Vo l u m e 8 Issue 2 Ye a r 2 0 0 9 LITERAT U R E R E V I E W Literature Review: FDA: Early Communication about an Ongoing Safety Review of clopidogrel bisulfate (marketed as Plavix) Peter R. McNally, DO.....................................................................................................18 F E AT U R E D M O V I E Featured Movie: Splenic Vein Gas : EUS Anatomy and the Visible Human John C. Deutsch, M.D....................................................................................................22 Editor’s Column || John C. Deutsch, M.D. Editorial: Non Steroidal Anti Inflammatory Agents in Gastroenterology This issue of VHJOE presents an article and a commentary regarding the potential for gastrointestinal complications associated with chronic use of non steroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). The case report, by McNally, et. al., demonstrates the utility of a combined operative endoscopic and surgical management of NSAID induced small intestinal stricture. In the “Capsule Endoscopy” section of the journal, Dr. Radwin, reviews the video capsule endoscopy findings with NSAID enteropathy and discusses the management issues related to capsule retention. NSAID Enteropathy and Capsule Retention; Complication or Guide to Therapy by Martin I. Radwin discusses anatomic changes which can be caused by these agents, as well as diagnostic and therapeutic interventions which may be required. These articles should help the reader in their approach to both NSAID complications as well as a more general approach to capsule endoscopy. For the readers enjoyment, I have included a video of Visible Human anatomy which corresponds to a capsule endoscopy exam of the upper intestine. As can be gathered from the article and commentary, capsule endoscopy is a valuable tool in assessing small bowel injuries, although Video Clip 1: Visible Human model and it is not a risk free cross sectional anatomy which corresponds procedure. Capsule to a small bowel capsule evaluation of the duodenum. retention can occur and can lead to surgery. Patency capsules are a relatively new method to lessen the risk, and it is important for capsule endoscopists to be familiar with the use of these items. Visit us online at www. vhjoe.org 11 Vo l u m e 8 Issue 2 Ye a r 2 0 0 9 Article || P. Alexander McNally, BS; Lonnie L. Imlay, MD; Joseph Pineau, MD; Peter R. McNally, DO NSAID Induced Small Bowel Strictures Managed by Combined Operative Endoscopy and Surgical Resection: A Case Report and 5 year Follow Up. Keywords: NSAIDs enteropathy, small bowel strictures, bowel obstruction, and capsule endoscopy. Disclaimers: none Abstract: We report a case of a 56 year old, Caucasian female with recurrent small intestinal obstruction caused by NSAID induced small bowel strictures. NSAID strictures in the small bowel were discovered by PillCam SB (Given Imaging, Ltd Yoqneam, Israel) endoscopy. Operative endoscopy was successful in limiting the length of small intestine resected by endoscopic dilation of multiple small bowel strictures and retrieving the retained SB capsule. As of January 2009, the patient has remained symptom free for 5 years. Case Report: This patient presented to our emergency department twice in the summer of 2004, with over four hours of acute onset abdominal pain and distention. On each occasion flat and upright abdominal films identified dilated loops of small intestine and air fluid levels. CT scan of the abdomen with intravenous and oral contrast was remarkable for small bowel dilation but without obvious cause, Figure 1. The patient had no history of prior abdominal surgery and colon cancer screening at 50 yrs was negative. Brief hospitalization with narcotic analgesia and nasogastric bowel decompression was effective in resolving symptoms. The patient resumed her usual activities and diet without limitation. An outpatient UGI small Figure 1: CT scan of abdomen showing dilation of small bowel loops. bowel follow through (SBFT) examination was scheduled, but not completed by the patient. Roughly, three months later the patient presented to the emergency department with similar symptoms and radiographic findings of small bowel obstruction. Laboratory tests 2 showed iron deficiency anemia. After brief hospitalization with intravenous fluids, narcotic analgesia and nasogastric decompression, the patient returned to baseline. Coloileoscopy showed only a few sigmoid diverticuli and upper endoscopy showed a small hiatal hernia and esophagitis. Biopsies of the Figure 2: UGI series with dedicated small bowel follow through. No stomach and duodenum identified only obvious bowel stenosis, dilation, or obstruction. Helicobacter negative, chronic gastritis. A dedicated UGI series with SBFT was carefully conducted and reviewed, but noted to be unremarkable, Figure 2. The patient’s past medical history was remarkable for seropositive rheumatoid arthritis, hyperparathyroidism, oral herpes simplex and gastroesophageal reflux. The patient had a past medical history of subtotal parathyroidectomy. Medications included Prilosec (omperazole) 20 mg daily, Plaquenil (hydroxychloroquine sulfate) 200 mg daily, Motrin (ibuprofen) 400 mg or 800 mg twice daily for over 8 years, and periodic prednisone for flares of rheumatoid arthritis. After a careful multidiscipline review of all studies and discussion with the patient, we felt the most likely cause of the patient’s recurrent symptoms was NSAID enteropathy or other obstructive etiology that would necessitate e x p l o r a t o r y abdominal surgery. Figure 3: PillCam SB showing white septae diaphragms. The diaphragms appear white by capsule endoscopy, because the peristaltic pressure of the capsule pressed on them causes capillary blanching - they are not white when viewed endoscopically. Visit us online at www. vhjoe.org We advised the patient that capsule endoscopy could give additional information as to the cause and location of recurrent small bowel obstruction, but there was a high likelihood that the capsule would not pass or would impact at the sight of the small bowel Figure 4: PillCam SB showing pathology. The patient circumferential white septae. gave informed written consent to proceed with capsule endoscopy, with knowledge that PillCam retention was likely. Images from the videocapsule showed multiple white septal strictures in the small intestine, Figures 3,4,5. Although the patient had no obstructive symptoms, the capsule did not pass spontaneously by two weeks. Surgical and gastrointestinal specialties planned for tandem operative intervention. After vertical midline incision, the small intestine was manually examined Figure 5: PillCam SB showing final recorded images of white septae and and confirmed the luminal debris at the obstructing ileal presence of multiple stricture. jejunal and ileal strictures, Figure 6. A palpable luminal defect (video capsule) was identified in the mid ileum. A pediatric colonoscope (Olympus PCF140L, 11.3mm Diameter, 3.2mm Channel, 168cm working length) was passed per os. The endoscopist advanced the colonoscope into the pylorus. Then the surgeon applied gentle pressure to the anterolateral aspect of the stomach to splint the endoscope and facilitate passage of the endoscope into the jejunum. From this point the Figure 6: Operative image of the serosal surface of the jejunum. Three endoscope was gently segmental strictures are seen and the advanced per os by tip of the endoscope lies beneath the the endoscopist with surgeon’s thumb. simultaneous gentle surgical traction and pleating of the small intestine over the tip of the endoscope and then gently sleeved over the length of the endoscope. As the endoscope was advanced multiple white circumferential strictures of variable diameter were evident in the distal jejunum, Figures 7,8. Vo l u m e 8 Issue 2 Ye a r 2 0 0 9 When the endoscope was advanced into the ileum, three consecutive strictures spaced over 1012 inches were encountered that obstructed passage of the colonoscope. With hand occlusion of the distal ileum Figure 7: Operative endoscopic image of sequential luminal strictures. by the surgeon, the endoscopist distended the lumen with air. The circumferential band-like nature of the strictures was evident. Through the scope (TTS), graded balloon dilation (12, 13.5, 15 mm OD and 240 cm length, CRE™ Wireguided Balloon Dilator, Boston Scientific Corp) was effective in disruption Figure 8: Operative endoscopic of the strictures. Mild image of luminal stricture with circumferential ulceration. intraluminal bleeding was evident and the endoscope easily advanced to the next obstructing stricture, where graded balloon dilatation was repeated twice more, Figures 9A,B,C. Ultimately the PillCam capsule was identified. Beyond this was a much denser luminal structure with luminal narrowing of ~5 mm, Figure 10. Graded balloon dilation was attempted, but at a 50% reduction of recommended pressure for a 12 mm CRE balloon dilation Figure 9A: Operative endoscopic image of CRE balloon dilation, pre-dilation. Visit us online at www. vhjoe.org 3 Vo l u m e 8 Issue 2 Ye a r 2 0 0 9 Figure 9B: Operative endoscopic image of CRE balloon dilation, intra-dilation. Figure 9C: Operative endoscopic image of CRE balloon dilation, post-dilation. gastrointestinal issues. a large serosal and mesenteric hematoma was evident, Figure 11. Examination of this stricture and the remainder of the ileum revealed a 10 cm segment of multiple, dense strictures and then normal distal ileum to the ileocecal region. The capsule was retrieved and a short segment of dense strictures in the distal ileum was surgically resected. The patient was managed in the usual post operative fashion and discharged from the hospital on a low roughage diet. She has been strictly prohibited from ingestion of any prescribed or over the counter NSAIDs and aspirin. At 5 years from surgery, this patient is well and has experienced no further bowel obstruction or other Discussion: NSAIDs are one of the most commonly used medications world wide, primarily because of their effectiveness as antiinflammatory and analgesic agents.1,2 Although NSAIDs have great benefit, significant morbidity and even mortality from chronic use of NSAIDs has been acknowledged in the upper gastrointestinal Figure 10: Operative endoscopic tract. A prospective image of tight stricture that impeded the passage videocapsule seen in the study by the Arthritis, foreground. Rheumatism, and 4 Aging Medical I n f o r m a t i o n System (ARAMIS) determined that 13 of every 1000 patients with rheumatoid arthritis who take an NSAID for 1 year have a serious gastrointestinal Figure 11: Operative image of complication.3 Most evolving serosal hematoma after physicians are aware of attempted CRE dilation of tight stricture shown in Figure 10. NSAID complications in the UGI tract to include pill esophagitis and gastroduodenal ulceration and hemorrhage, but only recently has the medical community become aware of the significant potential for NSAID injury of the small intestine.4,5,6,7 Prospective evaluation with capsule endoscopy has shown NSAID enteropathy to be very common in both healthy subjects and arthritic patients, with multiple small bowel erosions or ulcers discovered in over 70% of subjects treated with NSAID vs. 10% among control subjects.8,9 Small bowel enteropathy caused by NSAIDs has been hypothesized to occur through disruption of the mucosal and cellular integrity.10 NSAIDs act as lipid-soluble weak acids that interfere with enterocyte phospholipid membranes, uncoupling of mitochondrial phosphorylation, ultimately loss of mucosal barrier and cyclooxygenase-mediated compromise of villous blood flow.10,11 Small intestinal injury from NSAIDs runs a spectrum from macroscopically undetectable increased intestinal permeability and mild mucosal inflammation to ulceration to diagphragmatic strictures.4,5,12-15 Diaphragm strictures are rare but pathognomonic of NSAID use.4,5 There are often multiple, 2-3 mm thick septae, usually in the small intestine, which can reduce the size of the intestinal lumen to a pinhole.5,15,16 These diaphragm strictures are thin and easily missed on enteroclysis, where they may resemble plicae circularis.5 Our case illustrates several important clinical points concerning NSAID enteropathy and unexplained recurrent small bowel obstruction. First, in a patient with unexplained small intestinal obstruction on chronic NSAIDs and without previous abdominal surgery, NSAID enteropathy should be considered in the differential diagnosis. In this scenario, clinicians should not be surprised when endoscopic and radiographic testing are negative, as the obstructing diaphragmatic septae are easily and often missed, even on the most carefully conducted radiographic examinations.5,6 The utility of capsule endoscopy in this clinical situation is illustrated in the case we report. Secondly, the PillCam SB capsule (Given Imaging, Ltd Visit us online at www. vhjoe.org Yoqneam, Israel) dimensions are 11 x 26 mm, and should pass through the normal small intestine without difficulty. However, capsule endoscopy is usually conducted to evaluate for intrinsic pathology, such as occult gastrointestinal bleeding, anemia or possible Crohn’s disease. The benefit of discovery of occult small intestinal pathology, must be weighted against the risk of capsule retention, which has been reported to occur in 1% (investigation of obscure GI bleeding) to ~10% (investigation of suspected Crohn’s disease) of cases.17,18,19 Surprisingly, a retained videocapsule rarely impacts at a site of intestinal stenosis causing complete bowel obstruction.16,20-22 The Agile patency capsule (Given Imaging, Yoqneam, Israel) provides a means of evaluating luminal patency without the risk for capsule retention. The patency capsule is constructed from a dissolvable matrix, which is designed to disintegrate after 30 hours and pass though strictures in tiny pieces.23 Although the Agile patency capsule is helpful in evaluating the risk for capsule retention, it unfortunately does not provide luminal images. In our case, the patency capsule would have confirmed our preoperative suspicion of small intestinal stenosis, but would not have provided the key information on the number and extent of the NSAID enteropathy seen in our patient. Our preoperative suspicion of extensive NSAID enteropathy was confirmed by capsule endoscopy and guided our decision to proceed with tandem surgery and operative endoscopy. We hoped that surgically assisted enteroscopy would facilitate endoscopic positioning for TTS dilation of multiple strictures, monitor for complications of TTS dilations and preclude resections of long or even multiple segments of the small intestine. Our suspicions were confirmed, we cannot over emphasize the importance of visually monitoring the serosal surface during TTS of tight strictures for signs of injury that could have resulted in perforation or restenosis. At the time of this patient’s original presentation, balloon endoscopy was not available and not considered as an alternative to intraoperative endoscopy. Even now, the authors would suggest that the extensive nature of the NSAID enteropathy disclosed by capsule endoscopy in our report would still persuade us to proceed with a tandem surgical/operative endoscopic approach. Our experience of witnessing the serosal injury with dilation of tight NSAID strictures was helpful evaluating risk for bowel perforation. Had we followed the “rule of three,”24 for safe dilation of strictures, multiple sessions of balloon enteroscopy and sequentially larger TTS dilation sessions would have been needed to achieve luminal dilation of 15 mm used in our case. When small intestinal strictures are less numerous and less tight, single or double balloon enteroscopy and graded TTS dilation would be a less invasive option, shown to be useful by others.25,26 References inflammation in humans. Gastroenterol. 1987;93:480-9. 1. Cryer B. NSAID gastrointestinal toxicity. Current Opinion in Gastroenterology. 2000;16:495-502. 8. Graham DY, Opekun AR, Willingham FF, et al. Visible small intestinal mucosal injury in chronic NSAID users. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:55-59. 2. Wolfe MM, Lichtenstein DR, Singh G. Gastrointestinal toxicity of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. NEJM. 1999;340:18881899. 3. Singh G, Triadafilopoulus G. Epidemiology of NSAID-induced GI complications. J Rheumatol. 1999;26:Suppl 26:18-24. 4. Fortun PJ and Hawkey CJ. Nonsteroidal Inflammatory drugs and the small intestine. Current Opinion in Gastroenterology. 2007;23:134-141. 5. Adebayo D, Bjarnason I. Is nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) enteropathy clinically more important than NSAID gastropathy? Postgrad Med J. 2006;82:186-191. 6. Lang J, Price AJ Burke M, Gumpel JM, Bjarnason I. Diaphragm disease: pathology of disease of the small intestine induced by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. J Clin Pathol. 1988;41:516526. 7. Bjarnason I, Zanelli G, Smith T, Prouse P, Williams P, et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced intestinal Vo l u m e 8 Issue 2 Ye a r 2 0 0 9 Lastly, the technique of tandem surgery and operative endoscopy is an advanced surgical procedure that requires experience, skill, patience and cooperative planning.27,28,29 Our center has conducted a number of tandem procedures and suspect that disciplines of Surgery and Gastroenterology will continue to work more closely with NOTES, Rendezvous Laparoscopic cholecystectomy and ERCP, and therapeutic operative endoscopy. 9. Gomez-Rodriguez B, Cauendo-Alvarez A, Romero-Vasquez J, et al. NSAIDs erosive enteropathy assessed by capsule endoscopy: a prospective controlled trial. Gastroenterol. 2004;126:A96. 10. Bjarnason I, Takeuchi K, Simpson R. NSAIDs: the Emperor’s new dogma? Gut 2003;52:1376-1378. 11. Kelly DA, Piasecki C, Anthony A, et al. Focal reduction of villous blood flow in early indomethacin enteropathy: a dynamic vascular study in the rat. Gut. 1998;42:366-373. 12. Gargot D, d’Alteroche L, Desbazeille F, et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced colonic strictures: two cases and literature review. Am J Gastroenterol 1995;90:2035-2038. 13. Morris AJ, MacKenzie JF. Small bowel enteroscopy in undiagnosed gastrointestinal blood loss. Gut. 1992;33:887-889. 14. Maiden L, Thjodleifsson B, Theodors A. A quantative analysis of NSAID-induced small bowel pathology by capsule enteroscopy. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1172-1178. Visit us online at www. vhjoe.org 5 Vo l u m e 8 Issue 2 Ye a r 2 0 0 9 15. Goldstein JL. Videocapsule endoscopy to prospectively assess small bowel injury with celecoxib, naproxen plus omperazole, and placebo. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:133-141. 16. Cheifetz AS and Lewis BS. Capsule endoscopy retention: Is it a complication? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40:688-691. 17. Barkin JS, Friedman S. Wireless capsule endoscopy requiring surgical intervention. The world’s experience. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:A-83. 18. Pennazio M, Santucci R, Rondonotti E, et al. Outcome of patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding after capsule endoscopy: report of 100 consecutive cases. Gastroenterology. 2004;60:643-653. 19. Mow WS, Lo SK, Targan SR, et al. Initial experience with wireless capsule endoscopy in the diagnosis and management of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hep. 2004;2:3140. 20. Rondonotti E, Herrerias JM, Pennazio M, et al. Complications, limitations, and failures of capsule endoscopy: a review of 733 cases. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:712-716. 21. Delvaux M, Ben Soussan E, Laurent V, et al. Clinical evaluation of the M2A patency capsule system before a capsule endoscopy procedure in patients with suspected intestinal stenosis. Endoscopy. 2005;37:801-807. 22. Cave D, Legani P, deFrachis R, et al. ICCE consensus for capsule retention. Endoscopy. 2005 ; 62 :712-716. Article || Ryan M Harden, MD, MS; 23. Herrerias JM, Leighton JA, Costamanga G et al. Agile patency system eliminates risk of capsule retention in patients with known intestinal strictures who undergo capsule endoscopy. Gastroint Endosc 2008;67: 902-909. 24. Boyce HW. Dilation of difficult benign esophageal strictures. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:744-5. 25. Upchurch BR, Vargo JJ. Small bowel enteroscopy. Rev Gastroenterol Disord. 2008;8:169-77. 26. Aktas H, Mensink PB. Therapeutic balloon-assisted enteroscopy. Dig Dis. 2008;26:309-13. 27. Hammaker B and McNally PR. Utility of Emergent Endoscopy to Guide Laparoscopy in A Patient with Acute Cholecystitis and Unusual Laparoscopic Findings. http://www.vhjoe.org/ Volume5Issue1/5-1-3.htm 28. Wilhelm D, von Delius S, Burian M, Schneider A, Frimberger E, Meining A, Feussner H. Simultaneous use of laparoscopy and endoscopy for minimally invasive resection of gastric subepithelial masses - analysis of 93 interventions. World J Surg. 2008 Jun;32:1021-8. 29. Wilhelm D, von Delius S, Weber L, Meining A, Schneider A, Friess H, Schmid RM, Frimberger E, Feussner H. Combined laparoscopic-endoscopic resections of colorectal polyps: 10-year experience and follow-up. Surg Endosc. 2009 Jan 24. [Epub ahead of print] John C Deutsch MD; Jay L Parker, DO Angioedema Presenting as Abdominal Pain With Vomiting. Disclaimer: none. The authors reported no conflicts of interest regarding this report. clinical presentations including life threatening hypotension and airway obstruction. The case presented demonstrates a classic presentation of angioedema of the small bowel suggested by history, CT, EGD and confirmed with C1 esterase inhibitor assay. Introduction: Methods for Image Capture/Processing: Endoscopic Hereditary Angioneurotic edema (Angioedema) is a rare autosomal dominant condition in which there is a deficiency of functional C1 inhibitor(1) which leads to episodic interstitial fluid accumulation in the skin, larynx or gastrointestinal tract or other region leading to various Case Report Keywords: Angioneurotic Edema. Angioedema. 6 images were captured from endoscopy photographic images (Olympus) and digitized using Minolta Dimage A1 camera. This 21 year male presented to the emergency department in December of 2008 with a 12 hour history of cramping, mid- Visit us online at www. vhjoe.org epigastric abdominal pain and vomiting. He denied having this pain before and had no recent illnesses or illicit drug use. His pain was not associated with eating. His emesis was bilious and without Figure 1: CT scan showing distended hematemesis. He also stomach. denied constipation, diarrhea, melena, hematochezia urinary symptoms, pruritis, rash, fever and weight changes. CT scan in the emergency department suggested acute gastric outlet obstruction, as well as free abdominal fluid and bowel edema. (Figures 1-5) His symptoms started improving after receiving dilaudid, ondansetron and IV fluids in the emergency department. Figure 2: CT scan showing swelling near pylorus. The admitting diagnosis was “gastric outlet obstruction”. His past medical history was otherwise unremarkable and included depression, illicit drug use with drug-induced psychosis, and insomnia. Current medications included venlafaxine, olanzapine and zolpidem with no recent changes. He had no allergies. His family history was significant in that both his mother and grandfather had angioedema. His father had a myocardial infarction in his 40’s. Figure 3: CT showing free intraabdominal fluid. His physical exam included stable, normal vital signs. Patient appeared wellhydrated, healthy and in no distress. He had no swelling or hoarseness. Cardiorespiratory exam was normal. Abdomen was soft, without masses, rebound or guarding Vo l u m e 8 Issue 2 Ye a r 2 0 0 9 though he did have some moderate midepigastric tenderness to palpation. Laboratory analysis revealed an elevated white blood count of 14.7 with 93% PMNs, CBC was otherwise normal. His BMP was remarkable for a minimally elevated bicarbonate level of 30, BUN of 29, otherwise normal. His lipase was 15 and ionized calcium was 4.1. Figure 4: CT showing edema in distal duodenum and proximal jejunum. An upper gastrointestinal endoscopy with biopsy was performed after obtaining Figure 5: Coronal CT showing edema in informed consent distal duodenum. for the procedure. The EGD (Figures 6,7) revealed marked edema through the distal duodenum but without ulcerations or pathologic features. Biopsies of the jejunum revealed normal villus architecture with mild nonspecific chronic inflammation. The proximal duodenum was relatively normal. Gastric biopsy revealed chronic inflammation and numerous surface bacteria consistent with Helicobacter pylori infection. Based on the rapid improvement and family history, further laboratory studies were performed which included a normal TTG but low C4 level of 9 mg/ dL(normal 17-52 mg/dL), and low C1 Esterase inhibitor (C1 inh) antigen level of 5 mg/dL (normal 19-37 mg/dL). A diagnosis of Hereditary Angioedema Type I was made. Figure 6: Endoscopic image of distal duodenal edema. The patient’s symptoms completely resolved and he was discharged the day following admission. This patient was Visit us online at www. vhjoe.org 7 Vo l u m e 8 Issue 2 Ye a r 2 0 0 9 seen in allergy clinic and started on danazol, an androgenic steroid also known as 17alpha-ethinyl testosterone. Summary H e r e d i t a r y Angioedema (HAE) is an autonomic dominant condition Figure 7: Endoscopic image of relatively which causes normal proximal duodenum. recurrent non-pitting subcutaneous or sub mucosal edema involving the arms, legs, hands, feet, genitalia, trunk, face, tongue, larynx or bowel2 though clinical symptoms may vary.1 A prodrome may be present and attacks are occasionally associated with erythematic marginatum which makes it difficult to distinguish from anaphylaxis. Common triggers of these episodes include dental work, trauma, cold, medications including ACE Inhibitors, stress and pregnancy. Helicobacter pylori has been reported as an aggravating factor in this condition.3 There are two types of hereditary angioedema, Type I and Type II. Type I leads to synthesis of C1 inh, but it is not secreted by cells. Type II leads to synthesis and secretion of a non-functional C1 inh. More than 100 genetic abnormalities have been identified leading to hereditary angioedema and the prevalence is estimated at 1/50,000.4,5 References 1. Zuraw, Bruce L. Hereditary Angioedema. The New England Journal of Medicine 2008; 359: 1027-36. 2. Nzeako UC, Frigas E, Tremaine WJ. Hereditary angioedema as a cause of transient abdominal pain. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002 Jan;34(1):57-61. 3. Visy B, Füst G, Bygum A, Bork K, Longhurst H, Bucher C, Bouillet L, Cicardi M, Farkas H. Helicobacter pylori infection as a triggering factor of attacks in patients with hereditary angioedema. Helicobacter. 2007 Jun;12(3):251-7. 4. Bernstein IL. Hereditary angioedema: a current state-of-theart review, II: historical perspective of non-histamine-induced angioedema. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2008 Jan;100(1 Suppl 2):S2-6. 5. Pappalardo E, Caccia S, Suffritti C, Tordai A, Zingale LC, Cicardi M. Mutation screening of C1 inhibitor gene in 108 8 A similar type of condition, “familial angioedema,“ has been labeled angioedema Type III, though this proceeds through a different mechanism. The C1 inhibitor protein (C1 inh) attenuates the proteolytic manufacture of bradykinin and the loss or inactivity of this protein leads to elevated bradykinin levels which has been identified as a significant factor in angioedema.6 It is important the clinician understands this condition and disease process in order to avoid unnecessary workup and intervention. CT imaging shows edema7 which resolves in a relatively short time interval. In general, endoscopy with biopsy does not add specific information regarding the diagnosis of angioedema. However, endoscopy does allow inspection of the pharynx prior to insertion of the endoscope into the esophagus to evaluate for unexpected upper airway edema. Endoscopy also allows inspection for other conditions which could lead to abnormal small bowel imaging, such as sprue. Associated conditions, such as helicobacter infections can also be identified. Angioedema does not respond to typical therapies used in treatment of anaphylaxis though direct administration of fresh frozen plasma, epsilon-aminocaproic acid and danazol have been used.8 Cinryze, C1-esterase inhibitor product derived from human plasma, has recently been approved by FDA to prevent attacks of this condition.8,9 If there are no serious consequences of the attack (such as airway obstruction) most patients experience a resolution of their symptoms in 48-72 hours. unrelated families with hereditary angioedema: functional and structural correlates. Mol Immunol. 2008 Aug;45(13):3536-44. 6. Davis AE 3rd. The pathogenesis of hereditary angioedema. Transfus Apher Sci. 2003 Dec;29(3):195-203. 7. Wakisaka M, Shuto M, Abe H, Tajima M, Shiroshita H, Bandoh T, Arita T, Kobayashi M, Nakayama T, Okada F, Mori H, Uemura N. Computed tomography of the gastrointestinal manifestation of hereditary angioedema. Radiat Med. 2008 Dec;26(10):618-2.1. 8. Epstein TG, Bernstein JA. Current and Emerging Management Options for Hereditary Angioedema in the US. Drugs. 2008;68(18):2561-73. 9. Lavine G. C1-Esterase Inhibitor Infusion (Cinryze) to Prevent Hereditary Angioedema Attacks FDA approves new drug to prevent hereditary angioedema attacks. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2008 Nov 15;65(22):2080. Visit us online at www. vhjoe.org Capsule Endoscopy || Martin I. Radwin, M.D.. NSAID Enteropathy and Capsule Retention; Complication or Guide to Therapy? NSAID Enteropathy McNally et al. present an exemplary case report of stenosing NSAID-induced damage of the small intestine involving the cooperative use of several diagnostic and therapeutic modalities to obtain a successful long term outcome. In addition, this case queries a number of controversial issues surrounding the approach to the diagnosis and management of this heretofore under-recognized clinical disorder. The noted magnitude of anti-inflammatory use, the high frequency of small bowel pathology in normal volunteers1 and the relative rarity of such severe cases would suggest a spectrum of disease with the majority of patients subclinical and undiagnosed. Some authors have even suggested that NSAID damage of the small intestine may be more clinically relevant than NSAID gastropathy.2 The availability of wireless capsule endoscopy and deep enteroscopy rapidly changed the landscape of our ability to study the entity that we now call “NSAID enteropathy.” Prior to these modalities and actual visualization of the effects from these agents, surrogate information from indirect measurements of small bowel damage, using techniques such as permeability testing of intestinal integrity with Cr-EDTA Indium labeled leukocyte scintigraphy and fecal calprotectin,3 offered some insight into the epidemiology, protein loss and inflammatory component of this entity. Although pathologic features of NSAID damage were long appreciated in rats,4 one of the earliest direct observational studies of small intestinal mucosal damage in humans was performed with a balloon-assisted enteroscope to aid in the diagnosis of chronic blood-loss anemia.5 Subsequent use of intraoperative, push enteroscopy, and double-balloon enteroscopy has added to our knowledge of the pathologic and histologic features of this disorder. Unfortunately, these examinations are cumbersome, time-consuming, invasive and not always readily available. Therefore, capsule endoscopy has become the mainstay of our diagnostic and research approach to the study of NSAID enteropathy because of its ease of application, patient tolerance and non-invasive nature. The information obtained from a capsule study in this disorder far exceeds that which could be offered by radiologic techniques.6 Unfortunately, the varied findings such as small erosions or minor mucosal breaks to more severe stricturing diaphragms and ulcerations may have unclear clinical implications as the natural history of this entity is still as yet fully understood. The specificity of “pathognomonic” diaphragm disease has proven not as reliable as once thought. A compelling pilot Vo l u m e 8 Issue 2 Ye a r 2 0 0 9 study presented at the 2006 International Conference on Capsule Endoscopy (ICCE) by Bjarnason et al. revealed a 20% incorrect diagnosis rate by four experienced blinded clinicians when reviewing the studies of 18 patients with established Crohn’s disease and 13 patients with NSAIDinduced enteropathy.7 (See video quiz below) Capsule Retention The risk of capsule retention in diaphragmatic disease, such as in NSAID enteropathy or Crohn’s disease, is fairly high, although complete obstruction is rare.8,9 Capsule retention, as defined arbitrarily as a trapped capsule for at least 2 weeks, has been an area of significant controversy and concern amongst capsule users. Several high risk patients have been defined such as known Crohn’s disease, long term NSAID use, surgical adhesive disease or radiation therapy.10 Unfortunately, radiologic techniques have demonstrated significant inaccuracy at predicting retention after normal exams and even in the setting of tight strictures.11,12 Some investigators have conversely suggested that since retention usually occurs at a site of notable pathology, surgical or endoscopic therapy may be guided by this “complication” to an effective and definitive resolution of the problem.13 Currently, however, most still consider small bowel obstruction or documented stricture a contraindication to capsule endoscopy for the fear of retention and impaction. However, in one series, 19 cases of suspected small bowel obstruction underwent capsule endoscopy with only 4 retentions, none of which caused an acute, high grade small bowel obstruction requiring surgical remediation. These authors concluded that capsule endoscopy can be safely used to identify the etiology and site of a small bowel obstruction.13 Conservative practitioners, who may otherwise avoid the use of a potentially diagnostic capsule endoscopy in high risk patients, may presently use the Agile patency capsule (Given Imaging, Yoqneam, Israel) to assess functional patency of the small bowel (Figure 1). The device is an ingestible and dissolvable capsule made of a lactose/barium body surrounded by dissolvable plugs at each end and containing an internal radiofrequency identification (RFID) tag. The presence in the intestinal tract can be determined by an external scanner or alternatively with standard radiography. Identically sized as the capsule endoscope, the timer plugs at each end are designed to erode after about 30 hours allowing small intestinal fluids into the capsule body resulting in disintegration and passage if retained longer. Initial scanning or radiography is typically performed Visit us online at www. vhjoe.org 9 Vo l u m e 8 Issue 2 Ye a r 2 0 0 9 between 30-36 hours after ingestion. The patient is then followed if patency is unconfirmed by the continued presence of the capsule at first scanning, until it passes for closer examination. Qualitative visual and Figure 1 tactile assessment regarding the condition of the passed capsule body is a critical complimentary assessment of patency which is more important than time of passage. If softening or any deformation of the body is observed, regardless of the travel time through the gastrointestinal tract, patency would be considered highly suspect and capsule endoscopy should probably be avoided (Figure 2). A recent international, multicenter study by Herrerias et al. investigated the efficacy and safety of the Agile patency system in 106 patients with documented strictures on radiography.14 After Figure 2 ingesting the capsule, patients were scanned or radiographed at 3 intervals: 3238 hours, 68-72 hours and finally 94-100 hours or until the capsule was excreted and recovered by the patient. The capsule was qualitatively examined for disintegration regardless of time of passage. Patency was established if either the capsule passed “intact” or if the RFID signal was not detected by the 32-38 hour scanning or by radiography. If patency was established, the patient underwent standard capsule endoscopy. If patency could not be established during the first scanning, further determinations were performed at the subsequent intervals or until the capsule was recovered for examination. Of the 106 patients enrolled, 59 (56%) excreted the capsule intact and underwent a standard capsule study, while 47 (44%) were excreted in a deformed state and were excluded. Interestingly, 73% of the intact capsules were excreted by 60 hours after ingestion and in one patient up to 100 hours. In 26 (44%) of the patients, the capsule was excreted intact prior to the first scheduled scanning. The average passage time was 40 hours. All 59 subjects with intact capsules completed a standard PillCam study with no cases of capsule retention. Significant findings were found in 24 (41%) of the examinations. A total of 17 patients had adverse effects with the Agile capsule with only 3 considered severe consisting of pain and nausea. One of these severe cases was felt unlikely to be related to the Agile capsule. The authors concluded that the patency system is a safe and useful predictive tool in high risk contraindicated 10 patients, who would otherwise not benefit from the high yield of significant findings obtained on capsule endoscopy, by demonstrating successful passage of a similarly sized capsule. Several issues are raised by this study in clinical practice. The standard protocol for use of the Agile system dictates scanning close to but not later than 30 hours (Figure 3). If the RFID signal is present Figure 3 at this time, patency is not proven. However, it is clear from this study that passage of intact capsules may take up to 100 hours, most often due to slow transit through the colon. Practitioners using this system should therefore rely more on the qualitative assessment of the passed capsule condition than the time of passage. Otherwise, many patients who would benefit a PillCam study may be excluded. Patients should be strongly encouraged to retrieve the Agile capsule for evaluation despite the potential repulsiveness for some. In addition, the study didn’t evaluate those with deformed capsules as to the actual incidence of retention or obstruction with subsequent capsule endoscopy. It is possible that many of these patients would pass the PillCam eventually without clinical manifestations or need for invasive intervention. We have all experienced patients with known strictures or high risk manifestations who pass the capsule without any difficulty or may retain for months or longer with the rare need for endoscopic or surgical removal. In fact, as exemplified in the case by McNally et al., retention occurs at a site of significant pathology and can guide an elective approach, whether endoscopic such as balloon-assisted enteroscopy or intraoperative combined procedures for a therapeutic result. My experience has been complete acceptance and consent by patients of the strong potential for retention or even obstruction requiring surgery when fully explained and informed. These patients are desperate to have the exam because of the possibility of a resolution to their often chronic debilitating symptoms. Certainly, a retention requiring invasive intervention for a medically remediable condition would be unfortunate. Therefore, should we consider capsule retention in a symptomatic patient with stricturing disease a complication or a victory? The consequence of a procedure that can localize pathology where other diagnostics cannot is therapeutically desirable. The case presented by McNally et al. would probably not have had such a successful result if the anticipated and well informed capsule retention had not occurred. Every case should be considered individually, carefully assessing the probability and desirability of capsule retention as a diagnostic tool, possibly using the Agile system, before deciding whether to continue with a high risk exam. Visit us online at www. vhjoe.org Video Quiz Two patients are presented here followed by their blinded corresponding capsule images for the reader to match as an exercise in diagnostic acumen. Vo l u m e 8 Issue 2 Ye a r 2 0 0 9 Patient 1: 63 year old woman with a long standing history of osteoarthritis involving the cervical spine and hands who has been using Ibuprofen 600mg TID for several years. In the last 2 years, she has developed intermittent melenic stools and postprandial periumbilical cramping. Labs reveal an iron deficiency anemia and hypoalbuminemia with negative endoscopic studies for a bleeding source. Patient 2: 34 year old man with chronic diarrhea, abdominal bloating and colicky postprandial abdominal pain. During the last several months, he has observed maroon stools, low grade fevers, weakness, nausea and vomiting. An EGD revealed mild gastritis and colonoscopy was significant for mild colitis in the rectosigmoid. An ASCA was positive and the CRP was elevated. Visit us online at www. vhjoe.org 11 Vo l u m e 8 Issue 2 Ye a r 2 0 0 9 References 1. Maiden L, Thjodleifsson B, Theodors A, et al. A quantitative analysis of NSAID-induced small bowel pathology by capsule endoscopy. Gastroenterology 2005;128:1172-1178. 8. Barkin JS, Friedman S. Wireless capsule endoscopy requiring surgical intervention. The world’s experience [abstract]. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:A-83. 2. Adebayo D, Bjarnason I. Is nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) enteropathy clinically more important than NSAID gastropathy? Postgrad Med J. 2006;82:186-191. 9. Delvaux M, Ben Soussan E, Laurent V et al. Clinical evaluation of the use of the M2A patency capsule system. Endoscopy 2005;37: 801-807. 3. Davies NM, Saleh JY, Skjodt NM. Detection and prevention of NSAID-induced Enteropathy. J Pharm Pharmaceut Sci 2000;3(1):137-155. 10. Storch I, Barkin J. Contraindications to capsule endoscopy: do any still exist? Gastrointest Endosc Clin North Am 2006;16: 329-36. 4. Kent TH, Cardelli RM, Stamler FW. Small intestinal ulcers and intestinal flora in rats given indomethacin. Am J Pathol 1969;54:237-245. 11. Pennazio M, Santussi R, Rondonotti E et al. Outcome of patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding after capsule endoscopy: report of 100 consecutive cases. Gastroenterology 2004;126: 64353. 5. Morris AJ, Wasson LA, Mackenzie JF. Small bowel enteroscopy in undiagnosed gastrointestinal blood loss. Gut 1992; 887-889. 6. Costamagna G, Shah SK, Riccioni ME et al. A prospective trial comparing small bowel radiographs and video capsule endoscopy for suspected small bowel disease. Gastroenterology 2002;123:999-1005. 7. Bjarnason I, Voderholzer W, Adler S, Thjodleifsson B, Maiden L. NSAID-induced small bowel damage may be indistinguishable from that of Crohn’s disease by wireless capsule enteroscopy. The 5th International Conference on Capsule Endoscopy, March 6-7, 2006. Boca Raton, Florida. 12 12. Spada C, Spera G, Riccioni M et al. A novel diagnostic tool for detecting functional patency of the small bowel. Endoscopy 2005;37: 793-800. 13. Chiefetz AS, Lewis BS. Capsule endoscopy retention: is it a complication? J Clin Gastroenterol 2006;40(8):688-91. 14. Herrerias JM, Leighton JA, Costamanga G et al. Agile patency system eliminates risk of capsule retention in patients with known intestinal strictures who undergo capsule endoscopy. Gastroint Endosc 2008;67: 902-909. Visit us online at www. vhjoe.org Topic Review || Peter R. McNally, DO, FACP, FACG. Topic Review: Clopidogrel and PPI Competition for CYP2C19: “Heart Attack or Heartburn?” Platelet aggregation and thrombus production is the primary mechanism of acute coronary syndrome (ACS).1 The efficacy of clopidogrel in combination with ASA therapy has been clearly proven to reduce recurrent coronary events following acute myocardial infarction and the adverse cardiovascular outcomes associated with percutaneous cardiovascular interventions (PCI).2,3 The use of platelet inhibitor drugs as mono or combination therapy is now common place and has changed the management of ACS and the “standard of care” after PCI.4,5 Unfortunately, the improved cardiovascular survival provided by antiplatelet therapy has been confounded by a parallel increase in the occurrence of upper gastrointestinal events (UGIE). In 2008, leaders of the ACCF/ACG/AHA convened and published, “Expert Consensus Document on Reducing the Gastrointestinal Risks of Antiplatelet Therapy and NSAID Use.”6 These societies carefully reviewed the risks and the potential benefit of instituting prophylactic PPI therapy to minimizing UGIE and are outlined in Figure 1. Vo l u m e 8 Issue 2 Ye a r 2 0 0 9 Figure 2: Hepatic CYP450 Activation of Clopidogrel Increased awareness and understanding of the need for CYP2C19 activation of clopidogrel to effectively prevention ACS, has prompted reconsideration of the ACCF/ACG/AHA recommendations for the reduction of UGIE using PPIs, which are also metabolized through the CYP450 pathway, see Figures 3 and 4. The study by Gilard M, et al,16 reviewed in this issue of VHJOE, highlights the inhibitory pharmacokinetic effect of omperazole to decrease clopidogrel CYP2C19 activation and thereby a pharmacodynamic effect to increase platelet adhesiveness as measured by the Platelet Reactivity Index (PRI). Clopidogrel “poor” responders (defined as PRI >50%) were more common in the Omperazole group 60.9% vs. 26.7% in the placebo group (p < 0.0001).16 Deepak LB, et al. Circulation 2008; 118:1894-1909 Paralleling the observed increased risk for UGIE associated with antiplatelet therapy, has been the unexpected observed variance in the effectiveness of clopidogrel to prevent adverse cardiovascular events after acute myocardial infarction and PCI.7,8,9 Careful pharmacokinetic studies of clopidogrel have shown that this “prodrug” requires bioactivation through the hepatic cytochrome P450 isoenzyme pathway, with CYP2C19 isoenzyme most important, Figure 2.13 Genetic polymorphisms among CYP2C19 isoenzyme have identified decrease metabolic activity and direct decrease in clopidogrel activation in select patient groups (30% whites, 40% blacks, and 55% east Asian).14,15,16 Visit us online at www. vhjoe.org 13 Vo l u m e 8 Issue 2 Ye a r 2 0 0 9 New research data from two independent and large health care systems have identified adverse outcomes with the use of clopidogrel plus a PPI among patients discharged after hospitalization with a diagnosis of ACS.17,18 Juurlink, et al,17 conducted a large (n=13,636) population-based, nested case control study among Canadian patients aged > 66 yrs following discharge after acute myocardial infarction and determined that patients that experienced reinfarction within 90 days of discharge were more likely than event-free patients in the control group to have received concomitant therapy with clopidogrel and PPI. They further estimated that compared to no treatment, CYP2C19-inhibiting PPIs were collectively associated with a 40% relative increase in risk for recurrent myocardial infarction. Ho, et al,18 conducted a similar large (n=8,250) retrospective multicenter cohort study from 127 Veterans Affairs hospitals to assess the outcomes of patients taking clopidogrel with or without a PPI after hospitalization for acute coronary syndrome. Death or rehospitalization for ACS occurred in 20.8% (n=615) of patients taking clopidogrel without PPI and 29.8% (n=1,561) of patients taking clopidogrel with PPI, adjusted odds ration (AOR), 1.25, 95% (confidence interval, 1.11-1.41). Results of these and other studies, have prompted the Food and Drug Administration to launch an FDA: Early Communication about an Ongoing Safety Review of clopidogrel bisulfate (Plavix*) http://www.fda.gov/Cder/ drug/early_comm/clopidogrel_bisulfate.htm.19 This widespread FDA communication warns of the potential serious drug interaction between clopidogrel and the entire class of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) including PrilosecOTC, Figure 5. Confounding this class recommendation, is the knowledge that there is significant variance in the CYP450 metabolism of each of the PPIs and some appear to be preferentially metabolized by nonCYP2C19 pathways, i.e., pantoprazole (CYP2C9). It will require both pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic data to show which, if any PPIs are safe to use in conjunction with clopidogrel. Fortunately, the makers of clopidogrel (Plavix*), Sanofi-Aventis and Bristol-Meyers Squibb are working with the FDA to sponsor research to evaluate this issue. Until such time that safety studies are complete, all physicians will need to carefully evaluate the risk benefit ratio of coadministration of clopidogrel and PPIs. When both medications are required, selection of a PPI metabolized through a non-CYP2C19 pathway and spacing the administration of each medication by several hours may be helpful since the serum half-life short (1-2 hours) for most PPIs and competitive CYP450 interactions may be lessened.20 References: 1. Yusuf S, Zhao F, Mehta SR, et al. Clopidogrel in unstable angina to prevent recurrent events trial investigators. Effects of clopidogrel in addition to aspirin in patients with acute coronary syndromes without ST-segment elevation. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:494-502. 2. Gurbel PA, Bliden KP, Samara W, et al. Clopidogrel effect on platelet reactivity in patients with stent thrombosis: results of the CREST study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:1827-32. 3. Bliden KP, DiChiara J, Tantry US, et al. Increased risk in patients with high platelet aggregation receiving chronic clopidogrel therapy undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: Is current antiplatelet therapy adequate? J Am Coll Cardiol.2007;49:657- 66. 4. Antman EM, Hand M, Armstrong PW, et al. 2007 focused update of the ACC/AHA 2004 guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J AM Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:210-47. 14 5. Anderson JL, Adams CD, Antman EM, et al. ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina/ non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J AM Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:e1-157. 6. Bhatt DL, Scheiman J, Abraham NS, et al. ACCF/ACG/AHA 2008 Expert Consensus Document on Reducing the Gastrointestinal Risks of Antiplatelet Therapy and NSAID Use. A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Clinical Expert Consensus Documents. Circulation 2008;118:1894-1909. 7. Kim KA, Park PW, Hong SJ, et al. The effect of CYP2C19 polymorphism on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of clopidogrel: a possible mechanism for clopidogrel resistance. Clin Pharm Ther. 2008;84:735-41. 8. Desta Z, Zhao X, Shin JG, Flockhart DA. Clinical significance of the cytochrome P450 2C19 genetic polymorphism. Clin Pharmacokinetic 2002;41:913-58. Visit us online at www. vhjoe.org 9. Mega JC, Close SC, Wivott SD, Shen L, et al. Cytochrome P-450 Polymorphisms and Response to Clopidogrel. Engl J Med 2009;360:354-62. action of clopidogrel associated to aspirin. J Thromb Haemost 2006; 4:2508-9. 10. Pezalla E, Day D, Pulliadath I. Initial assessment of clinical impact of drug interaction between clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:1038-9. 16. Gilard M et al. Influence of omeprazole on the antiplatelet action of clopidogrel associated with aspirin: the randomized, double-blind OCLA (Omeprazole Clopidogrel Aspirin) Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008: 51:256-60. 11. Aubert RE, Epstein RS, Teagarden JR, et al. Abstract 3998: Proton pump inhibitors effect on clopidogrel effectiveness: the Clopidogrel Medco Outcomes Study. Circulation. 2008;118:S_815. 17. Juurlink DN, Gomes T, Ko DT, Szmitko PE, et al. A populationbased study of the drug interaction between proton pump inhibitors and clopidogrel. CMJA. 2009;180:713-8. 12. Mega JL. Close SL, Wivott SD, et al. Cytochrome p-450 polymorphisms and response to clopidogrel. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:354-62. 18. Ho PM, Maddox TM, Wang L, Fihn SD, et al. Risk of adverse outcomes associated with concomitant use of clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors following acute coronary syndrome. JAMA. 2009;301:937-944. 13. Frere C et al, Effect of cytochrome P450 polymorphisms on platelet reactivity after treatment with clopidogrel in acute coronary syndrome. Am J Cardiol 2008; 101:1088-93. 14. Trenk et al. Cytochrome P450 2C19 681G polymorphism and high on-clopidogrel platelet reactivity associated with adverse 1-year clinical outcome of elective percutaneous coronary intervention with drug eluting or bare-metal stents. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008; 51: 1925-34. 15. Gilard M et al. Influence of omeprazole on the antiplatelet Vo l u m e 8 Issue 2 Ye a r 2 0 0 9 19. FDA: Early Communication about an Ongoing Safety Review of clopidogrel bisulfate (marketed as Plavix) http://www.fda.gov/ Cder/drug/early_comm/clopidogrel_bisulfate.htm 20. Li XQ, Andersson TB, Ahlstrom M, Weidolf L. Comparison of inhibitory effects of the proton pump inhibiting drugs omperazole, esomprazole, lansoprazole, pantoprazole, and rabeprazole on human cytochrome P450 activities. Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 2004;32:821-827. Cases from the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology Kathryn M. Johnson, CPT, MC, USA; Angela Levy, COL, MC, USA; Fidelina Desoto-Lapaix, MD; Leslie H. Sobin, MD NSAID Ulcer Key Words: NSAIDs, colonic ulcer. Physical Exam: Introduction: On physical examination, his vital signs were within normal limits and BMI=25.4. Right lower quadrant tenderness was noted, but without rebound or guarding. Bowel sounds were present. A rectal exam revealed dark brown stool. History: A 60 year old African-American male with a history of alcohol abuse, cocaine dependence, chronic hepatitis C infection, degenerative joint disease, left hemicolectomy in 1994 for adenocarcinoma of the sigmoid colon and cholecystectomy in 1997 was seen prior to this presentation for iron deficiency anemia, and then presented to the emergency department with right lower quadrant pain and other symptoms spanning five days. He reported having watery diarrhea for the first two days of symptoms, after eating at a vendor. The watery diarrhea resolved, but his abdominal pain continued, with an additional symptom the day of presentation of formed stool with specks of blood. Laboratory Studies: WBC=10.4 K/cmm (nml) RBC=5.08 M/cmm (nml) Hemoglobin=14.5 g/dL (nml) HCT=44.5 % (nml) MCV=87.6 cmu (nml) RDW=22.9 % (high) PLT=174 K/cmm (nml) Visit us online at www. vhjoe.org 15 Vo l u m e 8 Issue 2 Ye a r 2 0 0 9 Glucose=104 mg/dl (nml) BUN=13 mg/dl (nml) Creatinine=0.9 mg/dl (nml) SGOT=232 IU/L (high) SGPT=89 U/L (high) Alkaline Phosphatase=59 U/L (nml) Amylase=38 U/L (nml) Lipase=39.3 U/L (nml) the ascending colon. Surgical resection was recommended. Procedure: The patient underwent a right hemicolectomy. Gross Pathology: Radiology Studies: A CT scan revealed circumferential annular mural thickening of the entire ascending colon, which resembled a longsegment apple-core like lesion. Endoscopy Studies: Endoscopy was performed and revealed a circumferential lesion with ulcerated areas, consistent with colon cancer, in Figure 1A In the ascending colon, there was an indurated, circumscribed, poorly delineated cobblestone like lesion located 3cm distal to the upper lip of the ileocecal valve. This lesion measured 2.5cm. in length and 3cm. in width. The lesion was composed of moderately broad firm rugae with multiple intervening narrow ulcers that measured in average 1mm. The mucosa of the broad rugae was shiny and ended in a sharp well defined manner at the margins of the ulcers. The cut surface of this lesion showed gross preservation of the bowel layers with the expected small distortions caused by the ulcers. Figure 1B Figure 1C Figure 1D Axial multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) images show circumferential mural thickening of the ascending colon (arrows) with surrounding inflammatory changes in the pericolonic fat. The luminal (mucosal) surface of the colon is irregular. The terminal ileum (arrowhead in B) is normal. Figure 2A Figure 2B Figure 2C Coronal MDCT images show that the mural thickening of the ascending colon extends to the hepatic flexure (arrow in B). Again noted is extensive mucosal irregularity. 16 Visit us online at www. vhjoe.org Histology: The sections from a 3cm indurated area of colon described grossly show submucosal fibrosis and crypt disarray, consistent with healing ulcers, as well as ulcers that lack mucosa and have a small amount of associated active inflammation. Overall, there is a paucity of inflammation, which is typical in cases of non-steroidal antiinflammatory drug Figure 1: Preserved architecture with an (NSAID)-induced isolated crypt abscess (4x). damage; however, there are scattered crypt abscesses and foci of cryptitis with prominent eosinophils. It is unclear whether they are part of the process or secondary to the stenosis. There are also areas of glandular atypia, but these are Figure 2: Crypt abscess with large population of eosinophils (10x). usually adjacent to healing erosions, the atypical areas are located in the regenerative zone and the epithelium matures at the surface, indicating regenerative atypia. Discussion: NSAIDs are the most commonly prescribed drugs in the Western world, but they are not without risks. There is a five fold increased risk of gastrointestinal hemorrhage or perforation in women over 75 who routinely use NSAIDs,1,2 and there is a ten to thirty fold increased risk of chronic refractory peptic ulcer in patients on long term NSAID therapy.1,3 However, the use of lower NSAID doses, proton pump inhibitors and the introduction of Figure 3: Discrete re-epithelialized ulcer with minimal surrounding inflammation (2x). cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) specific inhibitors have caused a decrease in serious gastrointestinal injury due to NSAID use. Although ulceration of the stomach and duodenum have been associated with NSAID use for quite some time,4,5 the toxicity effects of these drugs on the small and large intestine have only been investigated relatively recently.5,6,7,8 Vo l u m e 8 Issue 2 Ye a r 2 0 0 9 The endoscopic appearance of the colon in a patient using NSAIDs may be normal, or may display erosions, ulcers or Figure 4: Regenerative atypia in epithelium mucosal diaphragms, lining ulcer, lamina propria and submucosal fibrosis and closer view of crypt abscess which are believed with increased eosinophils (10x). to be pathognomonic of NSAID-induced injury.9,10 The luminal diameter of such mucosal diaphragms may be as small as 1mm. Circumferential linear ulcers are proposed to be the precursors to these mucosal diaphragms.11 To our knowledge, cases of “apple-core” lesions, such as ours, have not yet been described in the literature. The most common microscopic manifestation of NSAIDinduced colonic pathology is that of non-specific mucosal ulceration, but focal colonic crypt injury, such as cryptitis or crypt abscesses, is also common.1 NSAIDinduced colitis may morphologically mimic other forms of colitis, including inflammatory bowel disease, collagenous colitis, eosinophilic colitis and pseudomembranous Figure 5: Distinct submucosal fibrosis colitis1; however, under healed ulcer (2x). features that favor NSAID-induced injury include an increase in apoptotic bodies, intraepithelial lymphocytosis (similar to lymphocytic colitis) and unexpected tissue eosinophilia.1,12 In our case the lack of significant lamina propria inflammation and prominence of eosinophils within crypt abscesses are histologic clues to the correct diagnosis. The presence of ulceration in a background relatively devoid of increased inflammation is sometimes described as “clean ulceration” Figure 6: Discrete active ulcer with and is a typical finding only mild inflammation and partial reepithelialization (2x). in cases of NSAIDinduced colitis. Visit us online at www. vhjoe.org 17 Vo l u m e 8 Issue 2 Ye a r 2 0 0 9 The clinical history provided by the contributor was also supportive of the diagnosis. The patient had a three month history of NSAID use to alleviate joint pain. The opinions and assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors, and are not to be construed as official, or as reflecting the views of the Departments of the Army and Defense. References 1. Noffsinger A, Fenoglio-Preiser C, Maru D, Gilinsky N. Gastrointestinal Diseases. Washington, DC: American Registry of Pathlogy, 2007. 2. Wilcox CM, Shalek KA, Cotsonis G. Striking prevalence of over-the-counter nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use in patients with upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Arch Intern Med 1994;154:42-46. 3. Hawky CJ. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug gastropathy: causes and treatment. Scand J Gastroenterol 1996;220:124-127. 4. Silvoso G, Ivey KJ, Butt J. Incidence of gastric lesions in patients with rheumatic disease on chronic aspirin therapy. Ann Intern Med 1979;91:517-520 5. Odze R, Goldblum J, Crawford J. Surgical Pathology of the GI Tract, Liver, Biliary Tract and Pancreas. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2004. 6. Allison, MC, Howatson AG, Torrance CJ, et al. Gastrointestinal damage associated with the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. N Engl J Med 1992;327:749-754. 7. Davies NM, Saleh, JY. Detection and prevention of NSAIDinduced enteropathy. J Pharm. Pharmaceut Sci 2000;3:137-155. 8. Bjarnason I, Hayllar J, MacPherson AJ, et al. Side effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on the small and large intestine in humans. Gastroenterology 1993;104:1832-1847. 9. Lang J, Price AB, Levi AJ, Burke M, Gumpel JM, Bjarnason I. Diaphragm disease: pathology of disease of the small intestine induced by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. J Clin Pathol 1988;41:516-526. 10. Robinson MH, Wheatley T, Leach IH. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug-induced colonic stricture: an unusual cause of large bowel obstruction and perforation. Dig Dis Sci 1995;40:315319. 11.Going JJ, Canvin J, Sturrock R. Possible precursor of diaphragm disease in the small intestine. Lancet 1993;341:638-639. 12. Lee FD. Importance of apoptosis in the histopathology of drugrelated lesions in the large intestine. J Clin Pathol 1993;46:118122. Literature Review || Peter R. McNally, DO, FACP, FACG. Literature Review: FDA: Early Communication about an Ongoing Safety Review of clopidogrel bisulfate (marketed as Plavix). Influence of omeprazole on the antiplatelet action of clopidogrel associated with aspirin: the randomized, double-blind OCLA (Omeprazole CLopidogrel Aspirin) study Gilard M, Arnaud B, Cornily JC, Le Gal G, Lacut K, Le Calvez G, Mansourati J, Mottier D, Abgrall JF, Boschat J. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;51:256-60. Introduction: In this edition of VHJOE, Literature in Review, we highlight the important FDA: Early Communication about an 18 Ongoing Safety Review of clopidogrel bisulfate (marketed as Plavix). http://www.fda.gov/Cder/drug/early_comm/ clopidogrel_bisulfate.htm This widespread FDA communication warns of the potential serious drug interaction between clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs). Both of these medicines are “prodrugs” requiring hepatic metabolism for activation. Unfortunately, each medicine is metabolized through the same hepatic CYP450 pathway, and competitive inhibition by each leads to decreased activation for both. We have chosen the article by Gilard, et al, to review, because it offers an objective, readily available, and validated measurement (Platelet Reactivity Index, PRI) of this drug interaction and the significant increased risk of Acute Visit us online at www. vhjoe.org Coronary Syndrome for persons simultaneously prescribed clopidogrel and omeprazole. The article by Gilard, et al, specifically examines the effect of omeprazole on the effect of clopidogrel on PRI, but can be extrapolated to evaluation of the effect of all available PPIs on the platelet inhibitor effects of clopidogrel. Aim PowerPoint: In a prospective, randomized double-blind study, Gilard, et al, evaluated the impact of OMP 20mg/day vs. placebo on clopidogrel effect by measuring platelet phosphorylationVASP as expressed as PRI. Platelet activation & aggregation play an important role in the pathogenesis of arterial thrombosis and can lead to acute coronary syndrome (ACS) associated with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Clopidogrel (Plavix*) a thienopyridine, inhibits platelet activation induced by adenosine diphosphate (ADP). Clopidogrel metabolites form an inactive disulfide bond with the platelet P2Y12 ADP receptor, inhibiting platelet reactivity. Clopidogrel is a prodrug, needing hepatic metabolism to acquire platelet anti-aggregation properties. Vasodilator-Stimulated Phosphoprotein Phosphorylation (VASP) provides an functional index of platelet reactivity to clopidogrel. The authors sought to test the hypothesis that OMP reduces the biological action of clopidogrel (platelet reactivity index or PRI) , probably due to competitive inhibition of the CYP2C19 pathway. Vo l u m e 8 Issue 2 Ye a r 2 0 0 9 Study Design: Prospective, blinded, placebo controlled, randomized trial Consecutive patients undergoing elective coronary stent implantation were considered for inclusion All patients gave written informed consent Controlled Treatment (all patients received) - Aspirin 75 mg/day - Clopidogrel 300 mg loading, followed by 75 mg/day Randomization Treatment - Omperazole 20 mg or Placebo - Treatment daily for 7 days The higher the platelet reactivity index (PRI) the more frequently thrombosis occurs with clopidogrel treatment. Randomized N = 140 The hepatic CYP450 isoenzyme CYP2C19 is the dominant enymatic pathway of prodrug (clopidogrel) activation. Omeprazole (OMP) is a racemic compound commonly used to suppress gastric acid production in the treatment of peptic ulcer disease and Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD). OMP is a prodrug, predominantly metabolized by hepatic CYP450 isoenzyme CYP2C19. Competitive inhibition of the CYP2C19 metabolic pathway by OMP may decrease Clopidogrel activation thereby decreasing PRI values and increasing risk for ACS. N = 70 Omeprazole N = 70 Placebo Evaluable n = 64 (drop outs, 6) Evaluable n = 60 (drop outs, 9) Total Assessed for Eligibility, N=354 Study Design: Study Population: Exclusion Criteria - Previous treatment with Clopidogrel - Previous treatment with PPI - History of thrombocytopenia < 150K - Bleeding disorder - Liver disease - Peptic ulcer disease - Pregnancy Visit us online at www. vhjoe.org 19 Study Design: Study Evaluations Study Results: Platelet Reactivity Index (PRI) Conducted on Day 1 (pre-Clopidogrel) and 7 days after (clopidogrel + OMP vs. placebo) Platelet Reactivity Evaluation - Vasodilator-Stimulated Phosphoprotein (VASP) BiodisStago, Asnieres, France. - Platelet mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) - Platelet Reactivity Index (PRI) Platelet Reactivity Index (PRI) calculation: 100 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 % PRI = (MFI[PGE1] - MF1[PGE1+ADP] X 100 MFI (PGE1) Established Criteria for Clopidogrel response: Good % PRI < 50% Poor % PRI > 50% Study Results: Demographics Placebo N=60 Omeprazole N=64 P-value 63 62 ns ♂ Gender 75% 81% ns Smoker 71% 64% ns HTN 47% 53% ns FHx CAD 43% 34% ns DM 18% 9% ns BMI 27 27 ns 71% 66% ns Age Dyslipidemia Omp D1 Plac D1 Omp D7 Plac D7 0 -10 -20 -30 -40 -50 -60 -70 P < 0.0001 Placebo Omp Study Results: Summary Baseline demographic characteristics between the Omp and placebo treated groups were statistically similar, Table 1. Day 1, mean PRI was similar in both groups (83.9% vs. 83.2%), but PRI on Day 7 was significantly higher in the Omp group (51.4% vs.. 39.8%), (p< 0.0001) Figure 1. Clopidogrel “poor” responders (defined as PRI >50%) were more common in the Omp group 60.9% vs. 26.7% in the placebo group (p < 0.0001). Table 1 20 P < 0.0001 Study Results: Variation of PRI PRI Variation (%) P = NS PRI (%) Vo l u m e 8 Issue 2 Ye a r 2 0 0 9 Placebo N=60 Omeprazole N=64 P-value Previous MI 8% 11% ns Beta-blocker 91% 83% ns Ace Inhibitor 50% 48% ns Atorvastatin 68% 67% ns Other statin 28% 23% ns The odds ratio of being a clopidogrel “poor” responder when treated with Omp was 4.31 (95% CI 2.0 to 9.2). Conclusions: Omp significantly decreased the effect of clopidogrel on platelet activation as tested by VASP phosphorylation. Clinical implications of this study suggest that 1/3 of patients on clopidogrel alone are unprotected against ACS (PRI > 50%) and that patients co-treated with Omp have double the risk of ACS (60.9% have PRI > 50%). Visit us online at www. vhjoe.org The empiric prescription of Omp to prevent the potential of gastrointestinal bleeding caused by aspirin-clopidogrel antiplatelet therapy should be stopped. Risk stratification for GI complications should guide Omp use in these patients. Reviewer Comments Gilard, et al, do not answer the following questions? Although all of the PPIs are prodrugs with some metabolism through the CYP450. Each PPI has unique CYP450 metabolic pathways. This study does not determine if all PPIs convey the same negative effect on clopidogrel (PRI > 50%) as shown with Omp. PPI with important negative clinical implication for the coadministration of omp and clopidogrel among patients at risk for ACS. This study design should be applied in a similar fashion to evaluate the effect of other PPIs on clopidogrel and the ACS risk measured by PRI > 50%. Vo l u m e 8 Issue 2 Ye a r 2 0 0 9 For now, we should all use restraint in the prescription of PPI among patients on clopidogrel and follow the current recommendation of the FDA until further studies are available. Primary Pathway (Secondary pathway) Omperazole CYP2C19 (CYP3A4) Esomperazole CYP3A4 (CYP2C19) Lansoprazole CYP3A4 (CYP2C19,CYP1A) Dexlansoprazole CYP2C19 (CYP3A4) Rabeprazole CYP2C19 + CYP3A4 Pantoprazole CYP2C9 (CYP2C19 Æ sulfate conjugation) The investigators did not evaluate for CYP2C19 polymorphisms or other confounding variables that may have influenced clopidogrel hepatic metabolism and explained high PRI (>50%) seen in 30% of the placebo group. Dr. Gilard and colleagues are commended for using a readily available clinical assay (VASP phosphorylation) to demonstrate the effects of Omp on clopidogrel inhibition of the ACS marker, PRI. The study is well designed, the results striking and References: 1. Frere C et al, Effect of cytochrome P450 polymorphisms on platelet reactivity after treatment with clopidogrel in acute coronary syndrome. Am J Cardiol 2008; 101:1088-93. 2. Trenk et al. Cytochrome P450 2C19 681G A polymorphism and high on-clopidogrel platelet reactivity associated with adverse 1-year clinical outcome of elective percutaneous coronary intervention with drug eluting or bare-metal stents. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008; 51: 1925-34. 3. Gilard M et al. Influence of omeprazole on the antiplatelet action of clopidogrel associated with aspirin: the randomized, double- The identification of increased risk for Acute Coronary Syndrome when at risk cardiac patients receiving clopidogrel are concomitantly given PPIs has lead to the Food & Drug Administration to issue the following warning: “Healthcare providers should continue to prescribe and patients should continue to take clopidogrel as directed, because clopidogrel has demonstrated benefits in preventing blood clots that could lead to a heart attack or stroke.” “Healthcare providers should re-evaluate the need for starting or continuing treatment with a PPI, including Prilosec OTC, in patients taking clopidogrel.” “Patients taking clopidogrel should consult with their healthcare provider if they are currently taking or considering taking PPI, including Prilosec OTC.” blind OCLA (Omeprazole Clopidogrel Aspirin) Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008: 51:256-60. 4. Gilard M et al. Influence of omeprazole on the antiplatelet action of clopidogrel associated to aspirin. J Thromb Haemost 2006; 4:2508-9. 5. Small DS et al. Effects of the proton pump inhibitor lansoprazole on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of prasugrel and clopidogrel. J Clin Pharmacol 2008; 48: 475-484. 6. Siller-Matula JM et al. Effects of pantoprazole and esomeprazole on platelet inhibition by clopidogrel. Am Heart J 2009; 157:148e1-148.e5 Visit us online at www. vhjoe.org 21 Vo l u m e 8 Issue 2 Ye a r 2 0 0 9 Featured Movie || John C. Deutsch, M.D. Featured Movie: Splenic Vein Gas : EUS Anatomy and the Visible Human The featured movie for this issue shows an example of how digital anatomy can help explain pathologic conditions. A47 yr old patient with a history of cirrhosis from hepatitis C and alcohol was found to have weight loss and abdominal Figure 1: Visible Human model pain. A CT scan was showing the splenic vein, portal vein and proximal superior mesenteric vein. read which suggested possible splenic The left adrenal and spleen are added. a The aorta is shown and an arrow infarct and there was identifies the celiac artery. a question raised regarding splenic vein thrombosis. EUS was performed to further evaluate the CT findings. The video shows the CT images of note and a model (Figure 1) of some relevant anatomy with the spleen, splenic vein, left adrenal and celiac artery. A cross Figure 2: Visible Human cross section from the sectional anatomy that approximates the subsequent EUS images. Visible Human (Figure 2) shows images similar to what would be found during radial array EUS. The EUS images show hyperechoic material traveling from right to left, as would be expected in flow from the splenic vein towards the portal vein. We hope this video demonstrates how digital anatomy and the Visible Human can be used to help familiarize readers with anatomic relations in this important abdominal region. Video Clip 1: Shows the CT images of note and a model of some relevant anatomy with the spleen, splenic vein, left adrenal and celiac artery. 22 Visit us online at www. vhjoe.org

© Copyright 2025