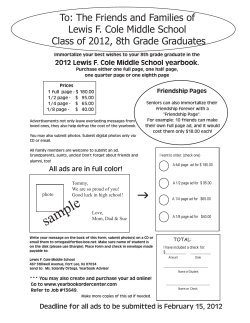

File