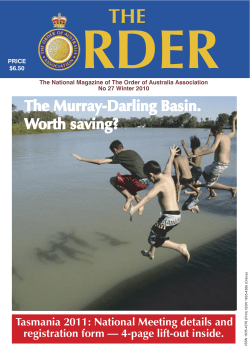

T B : D