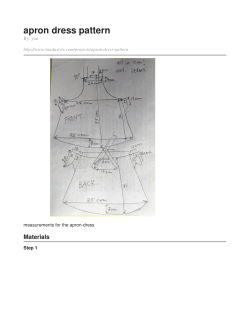

The January 2010