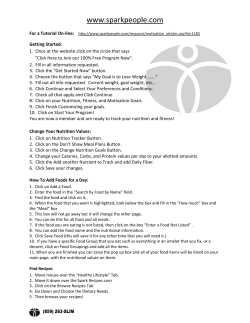

2012