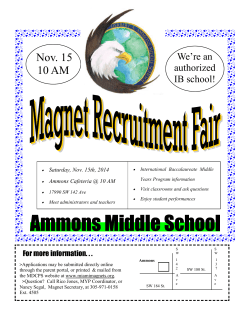

BUILD A BETTER