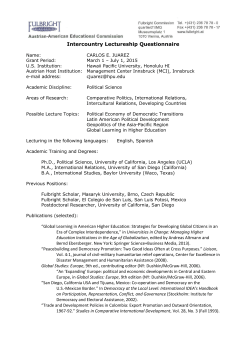

democracy after totalitarianism: the historical foundations of