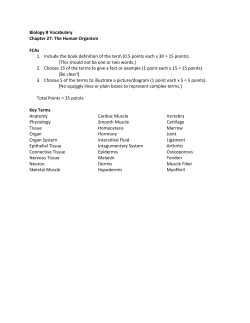

Bampton Thesis April 22 2015