Resource Guide: Finding the Origin of Your Immigrant Ancestors Barry J. Ewell

Resource Guide:

Finding the Origin of Your Immigrant Ancestors

Barry J. Ewell

Bj57barry@msn.com

Last Edit: March 23, 2007

INDEX

Introduction: Where are Permitt Lee and Maxey Ewell?

How to Use this Presentation

Definitions to Remember

A Methodology:

How to Find the Origin of Your Immigrant Ancestors

Step 1: Identify Important Information

to Know About Your Ancestor

Step 2: Start a Profile and Timeline of Your Ancestor

Step 3: Start Your Document/Record Search in America

Step 4: Review and Learn about Immigration Patterns

A Few Words about Maps

Beginning your Search

Step 5: Review Your Data: Is It Time to Track

Your Ancestor in the Country of Origin?

What Records to Search and Why:

Using the Paper Trail of Your Immigrant Ancestors

to Find Their Origins

Federal Census Records

How to use Census Records

Starting Points for Further Research

Death Records

How to Use Death Records

Starting Points for Further Research

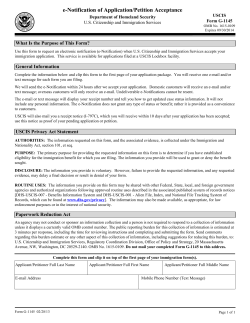

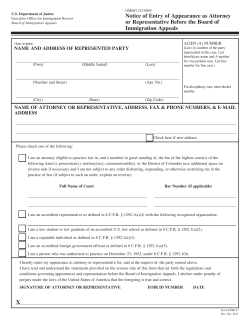

U.S. Naturalization Records

Pre-1906

Post-1906

How to Use Naturalization Records

Starting Points for Further Research

Ship's Passenger Lists

Prior to 1820

Between 1820 to about 1891

About 1891 to 1957

Available Immigration Passenger Lists

How to Use Passenger Lists

Starting Points for Further Research

Passport Applications

Starting Points for Further Research

Other Immigration Lists

Page

8

9

9

10

10

11

12

12

13

13

14

15

15

15

16

16

16

16

17

17

17

17

18

18

18

19

19

19

20

21

21

21

22

1

Probate Records

How to Use Probate Records

Starting Points for Further Research

Land Grants and Transfers

How to Use Land Records

Starting Points for Further Research

Social Security Applications

Starting Points for Further Research

Social Security Death Index

Starting Points for Further Research

Societies

Lineage/Hereditary Societies

Immigrant and Early Settler Societies

European Ancestry Societies

Nationality or Ethnic Lineage Societies

Genealogical Societies

Society Publications

Starting Points for Further Research

Military Records

Service Records

How to Use Service Records

Pension Records

How to Use Pension Records

Military History

Starting Points for Further Research

Cemeteries

How to Use Tombstones and Sexton Records

Starting Points for Further Research

Obituaries

Immigrant Church Records

Where to Find Archives for Major

U.S. Religious Denominations

Starting Points for Further Research

Township, City, County, and State

Histories and Biographies

Starting Points for Further Research

Colonial Town Records

Using Maps and Gazetteers to Help

Find Ancestor Origins

Locate Record Locations

Identify Changing Boundaries

Recognize Changes in Place Names

Topographical Features

Plot the Migration Patterns of Ethnic Group and Ancestors

Starting Points for Further Research

How to find your ancestor when you

hit a “brickwall” and you’re out of clues

Step 1: What do you know about your family?

Step 2: Find out what has been written

about the immigration/migration of

22

22

23

23

23

24

24

25

25

26

26

26

26

27

27

27

27

27

28

28

29

29

29

30

30

31

33

34

34

36

38

38

38

38

39

39

40

40

40

41

41

41

41

42

43

43

2

your ancestors country men.

Step 3: Learn what you can about immigration

patterns of the group/people from

which your family belonged.

Step 4: Compile what you have learned.

Step 5: Start a Systematic Search.

Start your search in America.

When ready, start your search in the country of origin.

43

43

44

44

44

44

Immigration/Migration Patterns:

Revealing Clues to Finding the Origin

of Your Immigrant Ancestors

47

Immigration/Migration Patterns

for the Genealogists: Think like a Historian

America: People on the Move

Starting Points for Further Research

African American Immigration

What are some of the important immigration facts?

Are there any clues to family naming patterns?

(Old Jones Naming Pattern)

Arab World Immigration

What are some of the important immigration facts?

Are there any clues to family naming patterns?

Asian Indian, Korean, and Southeast Asian Immigration

What are some of the important immigration facts?

Chinese, Japanese, and Filipino Immigration

What are some of the important immigration facts?

Czechs and Slovaks Immigration

Danish Immigration

Why and when did they come?

Where did they settle?

What were their social and work conditions?

Are there any clues to family naming patterns?

Dutch Immigration

What are some of the important immigration facts?

When and why did they come?

Where did they settle?

What was their religious background?

What were their social and work conditions?

Are there any clues to family naming patterns?

Eastern European Immigration

What are some of the important immigration facts?

English Immigration

What are some of the important immigration facts?

Why did they come?

When did they come?

Are there any clues to family naming patterns?

New England & Virginia Naming Patterns

Are there unique groups to remember?

What was their religious background?

47

47

49

50

50

50

51

52

52

52

53

53

54

54

55

56

56

56

56

56

58

58

58

59

59

60

60

61

61

62

62

62

63

63

64

64

64

3

Puritans

Where did the Puritans come from?

Finnish Immigration

When did they come and where did they settle?

Are there any clues to family naming patterns?

Forced Migrations

When did they come and where did they settle?

French Immigration

What are some of the important immigration facts?

When and why did they come?

New France

Louisiana

French Americans

Where did they settle?

What was their religious background?

German Immigration

What are some of the important immigration facts?

Why did they come?

When did they come?

Where did they settle?

What were their social and work conditions?

What was their religious background?

Are there other unique groups to remember?

Are there any clues to family naming patterns?

Greek Immigration

What are some of the important immigration facts?

Why did they come?

When did they come?

Where did they settle?

What were their social and work conditions?

Hungarian Immigration

Why did they come and where did they settle?

Icelandic Immigration

When did they come and where did they settle?

Are there any clues to family naming patterns?

Irish Immigration

What are some of the important immigration facts?

Why did they come?

When did they come?

Where did they settle?

What were their social and work conditions?

What was their religious background?

Are there any clues to family naming patterns?

Italian Immigration

What are some of the important immigration facts?

When did they come and where did they settle?

What were their social and work conditions?

Are there any clues to family naming patterns?

Jewish Immigration

What are some of the important immigration facts?

Are there any clues to family naming patterns?

64

65

67

67

67

69

69

71

71

71

71

72

73

73

74

76

76

76

76

77

78

78

79

79

80

80

80

80

80

81

83

83

84

84

84

85

85

85

86

87

87

88

89

90

90

90

91

92

93

93

93

4

Latino and Caribbean Migration and Immigration

Are there any clues to family naming patterns?

Mexican Immigration

Norwegian Immigration

Why did they come?

When did they come?

Are there any clues to family naming patterns?

Polish Immigration

Why did they come and where did they settle?

What were their social and work conditions?

What was their religious background?

Russian Immigration

Why and when did they come?

Where did they settle?

What were their social and work conditions?

What was their religious background?

Scandinavian Immigration

What are some of the important immigration facts?

When did they come?

Where did they settle?

What were their social and work conditions?

What were the naming patterns?

Are there any clues to family naming patterns?

Scottish and Scotts-Irish Immigration

What are some of the important immigration facts?

Scottish

When and why did they come?

Are there any clues to family naming patterns?

The Scotch-Irish

When and why did they come?

Where did they come from?

Where did they settle?

What was their religious background?

What were the naming patterns?

Additional Notes

Starting Points for Further Research

Research Libraries and Societies

Helpful Websites

Swedish immigration

Why did they come?

When did they come and where did they settle?

What were the naming patterns?

Welch Immigration

Why and when did they come?

Where did they settle?

Are there any clues to family naming patterns?

Westward Migration 1783-1912

1783–1912: When and why did they come?

Starting Points for Further Research on Migration

Migration Charts

Roads and Trails

94

94

95

96

96

96

96

98

98

99

99

101

101

102

103

103

105

105

105

106

106

106

106

108

108

108

108

109

110

110

111

111

111

112

112

113

113

114

116

116

116

117

118

118

118

118

120

120

120

121

121

5

Migrations From the Eastern States 1780s to 1840s

The Oregon Trail

Starting Points for Further Research

California Gold Rush

Starting Points for Further Research

Orphan Trains

Starting Points for Further Research

On the move: Life on Wagon Trains

Railroads

Starting Points for Further Research

Mail systems

Starting Points for Further Research

Homestead Act

Starting Points for Further Research

The Dust Bowl and the Okie Migration

Starting Points for Further Research

1000 Year North American Immigration Timeline: 1000 to 2002

123

125

126

127

128

129

129

130

133

133

134

134

135

135

136

136

138

State, County, and City Histories

Example of State History

Virginia History

Colonization

Royal Rule

Revolutionary Period

Post-Revolutionary Period

Civil War and Reconstruction

20th Century

Commonwealth

Starting Points for Further Research

SHG Resources: State History, 50 States

146

146

146

146

146

147

148

148

149

150

150

150

A Few Additional Resources by State

Alabama

Alaska

Arizona

Arkansas

California

Colorado

Connecticut

Delaware

District of Columbia

Florida

Georgia

Hawaii

Idaho

Indiana

Kansas

Kentucky

Louisiana

Maine

Maryland

151

151

151

151

151

151

151

151

151

151

151

151

152

152

152

153

153

153

153

153

6

Massachusetts

Michigan

Minnesota

Mississippi

Missouri

Montana

Nevada

New Hampshire

New Jersey

New Mexico

New York

North Carolina

North Dakota

Ohio

Oklahoma

Oregon

Pennsylvania

South Carolina

South Dakota

Tennessee

Texas

Utah

Vermont

Virginia

Washington

West Virginia

Wisconsin

153

153

153

154

154

154

154

155

155

155

155

155

155

155

155

155

156

156

156

156

156

156

156

156

156

156

156

Just in Case: Important Research Notes

and Practices for Finding Immigrant Ancestors

Learn How to Use the Web in Your Research

Research From your Desktop

Starting Points for Further Research

Search Engines

Online Databases

Learn to Use Google and Refine

Your Skills in Internet Searches

Verify Your Data

Field Research Is Still A Required genealogy Skill

In Search of a Name: A Few Helpful Reminders

Finding Clues in Family Naming Patterns

How to Increase Your Success in Finding the Ancestors Maiden Name

Starting Points for Further Research

Understanding Old Script

158

158

158

158

158

159

159

160

160

160

161

161

162

164

164

Resource

158

7

Ancestor Immigration and Migration

Keys to Unlocking Our Family History

Barry J. Ewell

Bj57barry@msn.com

Last Edit: March 23, 2007

Presentation Description

Where did your ancestors come from or live? Learn how you can use this information to understand your

heritage, important family decisions of the past, find genealogy records and so much more. Topics range

from questions to ask, where to search and find answers, and how to analyze historic information.

The following material is a compilation of personal experience and resources.

Introduction: Where are Permitt Lee and Maxey Ewell?

As a genealogist I have experienced the frustration of coming to an ancestor (in my case, Permitt

Lee, and Maxey Ewell), for which there seems to be no link to the old country or land of birth.

As I have consulted with other family genealogists, I have been in awe at the length our family

has gone to find our roots to no avail. I have searched on-line, collaborated through the message

boards, and traveled to the place of our family’s beginnings in Pennsylvania, Tennessee, North

Carolina, Kentucky, and Virginia. I have found and developed an extensive paper trail of the

family, and did find important clues, but not close enough to where I felt I was ready to jump my

search over the sea to my suspect home land.

After some thought, I decided to step away from my search and learn all I could about “How to

Find the Birthplace of My Ancestors. I researched

•

•

•

Methodologies, what others have done and suggested for searching for the homeland.

Records/artifacts that can reveal important clues that pinpoint or narrow the scope of ones

search.

How understanding immigration/migration patterns of ones ethnic heritage at a time and

place can yield rich insight not found in a document.

My search took me through hundreds of internet sites, books, and oral discussions. I was

overwhelmed at the massive amount of material that exists. When I finished, I understood how

documents, immigration patterns, and research methodology would combine to help find

ancestors. I had clarity of how to re-evaluate what I had, see the gaps and opportunities for

further research, and renewed hope that I would find the answers.

The design of this paper is to share with you a consolidated overview of my findings which are a

compilation of many talented experts in the field of genealogy and history. I have expanded my

original research so that I might be able to give other genealogists clues, ideas and direction for

finding their ancestors. While I would like to say I have every answer for every question you will

face, I can say you will have a good start of where to go next.

How to Use this Presentation

8

As you search for your ancestors, realize that it will take a combination of methodology,

tools/resources, and knowledge about your ethnic history to find your family roots. This

presentation is divided into the following sections to help you begin, continue, or renew your

search.

•

A Methodology: How to Find the Origin of Your Immigrant Ancestors

•

What Records to Search and Why:

Using the Paper Trail of Your Immigrant Ancestors to Find Their Origins

•

Immigration/Migration Patterns:

Revealing Clues to Finding the Origin of Your Immigrant Ancestors

•

Just in Case: Important Research Notes and Practices for Finding Immigrant Ancestors

Definitions to Remember

Assimilation. The way that someone who comes from a foreign land or culture becomes

absorbed into a culture and learns to blend into the ways of its predominant, or main, society.

Colony. A group of people living as a political community in a land away from their home

country but ruled by the home country.

Emigration. Leaving one's country to go to another country with the intention of living there.

Exiles. People who have been sent away from their homeland.

Immigration. To travel to a country of which one is not a native with the intention of settling

there as a permanent resident.

Migration. To move from one place to another, not necessarily across national borders.

Overlanders. People traveling west by land rather than by sea.

Topography. The surface features of a region, such as mountains, plateaus, or basins.

9

A Methodology:

How to Find the Origin of Your Immigrant Ancestors

Genealogy is a process, a methodology, for finding our ancestors. There are many tools

available, but it’s knowing what to use and when to use the tool that makes the difference.

I remember many years ago as a Boy Scout, a member of our troop became lost. The first thing

many of us did was rush right out and start looking in the wilderness and calling out his name.

We had no record of who had gone where, or what if anything was found. Any evidence that

may have been found was trampled over. As evening came, we built large bonfires, hoping he

might see us in the dark. As the morning came, we gathered as a troop and discussed what we

remember and what we know about his last where abouts. Next, we formed ourselves into groups

being led by an adult with one adult being the coordinator of our efforts. Each group was

assigned a specific area or quadrant to search. As we searched each quadrant, we either found a

clue of where he might be or where he wasn’t. As the day wore on, we found him asleep on the

trail not more than a mile from camp, a happy ending. The happy ending resulted not from our

hurry and scurry of the previous day but from a systematic method of searching that began the

next morning. The following is an approach to finding your ancestors through immigration

records.

Step 1: Identify Important Information to Know About Your Ancestor

What do you know about your ancestor? Gather and review all the documents you have relating

to your ancestor. I personally like to develop a spreadsheet that allows me to record each piece of

information by date. The following are a few questions to get started to review the information

you currently have:

1. What is the full name of ancestor? Was the name changed when they came to America?

If yes, identify what the name was before it was changed?

• Name of ancestor

• Name changes -- both given and surnames

2. What are the names of immediate family?

• Names of the parents and their birth places

• Names of siblings

• Name of spouse (s)

• Names of children

• Common names given to family members.

3. Identify the name of friends and relatives that are associated with your ancestor in

American and in the country of origin. It is a great help in making sure you have found

your ancestor when you find them together in the country from which they immigrated.

• Names of family and friends with whom they associated.

4. Identify an event (e.g., date, month, year [be as specific as possible]) associated with your

ancestor (e.g., birth, christening, marriage) which occurred in the country of origin. I

have found especially in the Scandinavian research many individuals may have the same

name and the only way to tell them apart is by the event date.

• Birth date/locality

5. What was the country of origin? Do you have the name of a village, town, and county?

This can be the most difficult piece of information to secure.

10

•

•

•

Localities lived in

Geographical clues

Historical clues

6. Was the ancestor you are searching for, really the first one to come to America? I have

found cases when my ancestor was a member of the family that came to America.

7. What other information do you have?

• Documents in your possession

• Information about culture and religion

• Time period of immigration

• Family stories and traditions

• Family heirlooms

Step 2: Start a Profile and Timeline of Your Ancestor

Take the information you know and begin a written profile and timeline. Use an existing form or

create one of your own to help track your ancestor’s information and what you find. Make sure

you also document where you find the information you record as the need will always arise to

review at least one of your data points to confirm or search deeper for information. I believe you

should record any and all information you learn about your ancestor not matter how insignificant

you consider it. Not only will it help in your search but once you find them, it will help in writing

family histories. The following are the types of information you should be finding:

• Name of ancestor

• Name changes -- both given and surnames

• Names of Parents and their birth places

• Names if siblings

• Name of spouse (s)

• Names of children

• Common names give to family members

• Names of family and friends with whom they associated

• Birth date/locality

• Localities lived in

• Geographical clues

• Historical clues

• Documents in your possession

• Information about culture and religion

• Time period of immigration

• Family stories and traditions

• Family heirlooms

At this point you should be able to clearly see some trends in your ancestor’s life. The types of

documents you are able to find are dependent upon where they live and time frame. Doublecheck that you've reviewed every document you have on your ancestor; this includes letters,

diaries, photographs in your files and in the possession of your relatives. Check the online

message boards for correspondence that you may not be aware of. Your ancestor’s life is

recreated one event at a time.

Now that you have your information written down, develop a timeline starting from their death

and moving toward their birth (reverse chronologically). What do you see? Any trends? What

11

don’t you see? What gaps do you see in the information? Write down “all” the questions you

still need and want to answer. No question is too small or out of bounds.

Don’t forget to include a search for items such as histories, sketches, photographs, letters, and

diaries as part of your search. Documents can be online, in libraries, or in a distant cousin’s file.

Step 3: Start Your Document/Record Search in America

Once you are fairly certain about the ancestor for which you are going to search, begin in

America to find records that will provide and confirm important information about your ancestor

and lead you where to look for records from countries of origin.

Based on the time period in which your ancestor lived, outline some of the documents that might

exist for your ancestor and where they might exist to help fill in the gaps and answer your

questions. Start with the paper trail you already have for your ancestor. You won’t be looking

for a birth certificate if your ancestor’s life predates civil registration. Start with the basics —

birth, marriage and death records, church documents, indentures, land records, court records and,

of course, immigration materials.

Try to find at least two records, more if possible, of your ancestors to help confirm and

collaborate information provided. Throughout your search, you will be exposed to resources that

range from oral discussions to information that you find in print, online, and on other types of

media (e.g., CD’s, tapes). It is important to always ask questions such as:

• What is fact? What is suspicion?

• Did I search for the entire family?

• Did I search a broad time period in this record?

• Did I search a wide enough geographical area?

• Did I search every location they lived in covered by this record?

• Did I search variant spellings of names in this record?

• Did I search for and record neighbors, family, and friends found in this record?

• Did I search for and use indexes?

• Do you understand this resource/record’s intention, what it offers, how it’s put together

and its limitation?

As you gather and review information, continue to add to your current ancestor profile and

timeline. Keep a detailed log of where you have been. As you continue the search you will

check-off questions answered and add new questions based on your findings. Keeping this list

up-to-date is vital to keeping focused and helping to shed light at times when you need

inspiration.

Step 4: Review and Learn about Immigration Patterns

One of the most important considerations in finding our ancestor is immigration research.

Look at immigration from an historian’s point of view and not from the genealogical point of

view. You’re trying to understand what your ancestors did and why. As a genealogist, you

wonder why your ancestors migrated. You look for clues that might direct you to the birthplace in

the country of origin. As genealogists the first thing we do is start searching through deeds, wills,

bible records, and other such documents. Documents can tell that your ancestor sold his property

from one person to another, but it does not tell why he picked up and moved from Virginia to

Tennessee. When you seek to understand immigration patterns of the time and people your

chances for success expand dramatically because you begin to understand what your family was

12

thinking, you see what other individuals were doing, where they were going, and where they

came from.

By learning about the immigration patterns for a specific ethnic group to which your ancestor

belonged in the time period they lived, you begin to see trends that correlate to your family such

as the ports they arrived at, the counties and cities from which they came and where they settled,

the reasons for decisions that were made, the types of records they left behind and where.

You start by answering the question:

• What was their ethnic background or group to which you think they belonged?

• Were they Puritans, Welch, or Germans?

Now you begin to answer the questions:

• Why did they come?

• When did they come?

• Where did the settle?

• What were their social and work conditions?

• What was their religious background?

• Are there any clues to family naming patterns?

A Few Words about Maps. Maps help trace the migration paths our ancestors took. More

detailed maps will show what routes were available at the time, including railroads, waterways,

early roads, etc. It is important to trace the path our ancestors took because there may have been

records created along the way. The naturalization process may have been started at the port of

entry, and the records may be scattered in stops along the route to the final destination. Ethnic and

religious groups often traveled together, and your ancestors' travels can be traced by tracking

others in their group. Also, on the long journey west in the United States, babies were born,

people married, and people died. There may have been records of events created along the way.

Beginning your Search.

Included in this paper are examples of immigration/migration profiles for the following countries

or regions. They provide an example of the type of information that is available to find the origin

of your ancestors as well as helping to better understand your ethnic heritage. See the section:

Immigration/Migration Patterns:

Revealing Clues to Finding the Origin of Your Immigrant Ancestors

Profiles included:

1. African American Immigration

2. Arab World Immigration

3. Asian Indian, Korean, and Southeast Asian Immigration

4. Chinese, Japanese, and Filipino Immigration

5. Czechs and Slovaks Immigration

6. Danish Immigration

7. Dutch Immigration

8. Eastern European Immigration

9. English Immigration

10. Finnish Immigration

11. Forced Migrations

a. African Americans

13

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

b. Arcadians

c. Japanese Americans WW II

d. Mormons

e. Native Americans

French Immigration

German Immigration

Greek Immigration

Hungarian Immigration

Icelandic Immigration

Irish Immigration

Italian Immigration

Jewish Immigration

Latino and Caribbean Migration and Immigration

Mexican Immigration

Norwegian Immigration

Polish Immigration

Russian Immigration

Scandinavian Immigration

Scottish and Scotts-Irish Immigration

Swedish Immigration

Welch Immigration

Westward Migration 1783-1912

a. Migrations From the Eastern States 1780s to 1840s

b. The Oregon Trail

c. California Gold Rush

d. Orphan Trains

e. On the move: Life on Wagon Trains

f. Railroads

g. Mail systems

h. Homestead Act

i. The Dust Bowl and the Okie Migration

1000 Year North American Immigration Timeline: 1000 to 2002

Example of State, County, and City Histories

Step 5: Review Your Data: Is It Time to Track Your Ancestor in the Country of Origin?

Review your data. At this point:

• You have confirmed the country of origin.

• You can put your ancestors in historical and social context.

• You have researched records and have developed a timeline of your ancestor’s life in the

new world.

• You’ve assigned a time period when the ancestor entered the country.

• Perhaps you can place your ancestor in a region, county, or city where they lived.

• Are you ready to start your search in the county of origin?

o If yes, congratulations. Now learn your resources and continue your search.

o If no, identify gaps and retrace your steps to see if you missed any important

clues. Often, it only takes one clue to get the break you need.

See the section: How to find your ancestor when you hit a “brickwall” and

you’re out of clues.

14

What Records to Search and Why:

Using the Paper Trail of Your Immigrant Ancestors

to Find Their Origins

The following are records and resources genealogists find extremely helpful and full of clues to

help find the birthplace of ancestors. The information provided is not listed in any particular

order. It is designed to provide a quick reference and direction of where to find and search for

records as probable places to find information.

Federal Census Records

Federal census records provide the building blocks of your research, allowing you to both

confirm information, and to learn more. The following is an outline of the type of information

From 1790-1840, only the head of household is listed and the number of household members in

selected age groups.

From 1850 to 1930, details are provided for all individuals in each household, such as:

• Names of family members

• Ages at a certain point in time

• State or country of birth

• Parent's birthplaces

• Year of immigration

• Street address

• Marriage status and years of marriage

• Occupation(s)

• Value of their home and personal belongings

• Crops that they grew (in agricultural schedules), etc.

How to use Census Records

Use naturalization records to

• Track your ancestors' movement over time

• Find names and rough birth years

• Determine relationships

• Learn birthplaces

• Find clues to the previous generation (e.g., birthplace)

• Learn street address

• Learn whether a slave or a slave owner

• Learn occupations

• Learn other country of birth

• Learn of other children who likely died young

• Learn year of immigration and/or naturalization

• Note naming patterns in your family

• Find clues to your family's economic status

• Find some clues to education

• Find some clues to military service

• Find some clues to medical conditions

• Narrow year and place of marriage

15

•

•

•

•

•

Learn about employment status

Learn about exceptional circumstances, such as convicts and homeless children

Learn native tongue

Narrow death dates

Identify other potential branches of your family living nearby

Starting Points for Further Research

Entire books have been written about how to work with census data. And you can find answers

to any question you have about a particular census with a Google search. See the Appendix:

“Learn to Use the Census.” The following are starting points to assist with the census.

Familysearch.org

http://www.familysearch.org/Eng/Search/frameset_search.asp?PAGE=census/search_cen

sus.asp

Links to Online Census Records

http://www.census-online.com/links/

US Census Help, Links & Online Records

http://home.att.net/~wee-monster/censuslinks.html

The National Archives

http://www.archives.gov/genealogy/

Death Records

Death certificates are usually the first source in which an official written account will reveal an

exact place and date of death, and a good chance of additional genealogical details, such as the

date and place of birth, name of father, maiden name of mother, name of spouse, social security

number, name of cemetery, funeral director, and the name of the informant (often a relative of the

deceased).

How to Use Death Records

Information is helpful to

• Find an approximate year of immigration or arrival in this locality

• Find an address to seek in deeds or city directories, locate on maps, or narrow your search

in an un-indexed census

• Identify employer records to pursue

Starting Points for Further Research

Starting points for searching for death records are as follows:

Where to Write for Vital Records

http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/howto/w2w/w2welcom.htm

United States Vital Records Information

http://www.vitalrec.com

Express Certificate Service

http://www.vitalchek.com

16

Ancestry.com

http://ancestry.com/search/

Rootsweb.com

http://resources.rootsweb.com/cgi-bin/townco.cgi

U.S. Naturalization Records

Documenting that an individual was granted citizenship in the United States. Naturalization

records provide a way to find arrival information for immigrant ancestors. Recent naturalization

records (those issued after 1906) also contain other significant genealogical information. Many

immigrants did become naturalized. Because citizenship was required to own land, serve in

public office, or to vote. Information varies greatly among documents and time period.

Pre-1906

Documents/records pre-1906 vary greatly from state to state because there were not federal

standards. You should at least be able to find:

• Country of origin

• Port of arrival

• Port of embarkation

• Date of arrival in the United States

Post-1906

Documents post 1906 can include:

• Name

• Current address

• Occupation

• Birthplace or nationality

• Birth date or age

• Marital status

• Name, age, and birthplace of spouse

• Names, ages, and birthplaces of children

• State and port of emigration (departure)

• State and port of immigration (arrival)

• Name of ship or mode of entry

• Town or court where the naturalization occurred

• Names, addresses, and occupations of witnesses

• Physical description and photo of immigrant

• Immigrant's signature

• Witness names

• Immigration year

• Additional documentation such as evidence of a name change

How to Use Naturalization Records

Use naturalization records to

• Find the country of origin for your ancestor (Pre/Post 1906)

• Narrow the timeframe to search for a ship passenger arrival list (Pre/Post 1906)

• Find clues of relatives or neighbors (Pre/Post 1906)

17

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Find an ancestor's signature (Pre/Post 1906)

Perhaps find another version of your ancestor's name (Pre/Post 1906)

Learn exact village or town your ancestor came from (Post 1906)

Learn immigrant's birth date and/or place (Post 1906)

Learn details of arrival in U.S. (e.g., name of ship, date, port of arrival, etc.) in order

to find ancestor's ship arrival record (Post 1906)

Obtain or confirm names, dates and/or birthplaces of wife and children (Post 1906)

Learn occupation (Post 1906)

Find marriage details (Post 1906)

Find a photograph of the ancestor (Post 1906)

Find evidence of a name change (Post 1906)

Find reference to other courts where the "first papers" may have been filed

(suggesting immigrant lived elsewhere for a while) (Post 1906)

Starting Points for Further Research

Starting points for searching for Naturalization records are as follows:

Naturalization Records: Introduction and Links to Resources

http://www.archives.gov/genealogy/naturalization/

Pledging Allegiance: Naturalization records by Julia M. Case, Myra Vanderpool

Gormley and & Rhonda McClure:

http://www.rootsweb.com/~rwguide/lesson16.htm

Ancestors: Immigration Records

http://www.byubroadcasting.org/ancestors/records/immigration/extra1.html

Examples of naturalization papers:

http://members.aol.com/rprost/natural.html

Ship's Passenger Lists

Chances are your ancestors came to America in a ship. Every ship had record of its passengers

known as a passenger list or manifest, many of which exist today. The information available on

these lists varies over time.

Prior to 1820

Most sailing ships were cargo ships and the passenger list may be found among ships cargo

manifest. Ships sailed only when the cargo hold was full. There is no consistency to the type and

amount of information that exists. The manifests were normally deposited at the port of arrival

and were originally kept at these colonial ports. Many of these early records have been lost or

destroyed. If they exist you will find them distributed among libraries, historical societies,

museums and private hands. If you are fortunate to find them, the type of information you may

find includes:

• Country (possibly province, or exact town of origin)

• Date of arrival in the U.S.

• Family members or others who immigrated on the same ship

• Destination in the U.S.

• Occupation, age, and sex

• Ship's name, its master, its port of embarkation, and its port of arrival

18

Between 1820 to about 1891

After immigration to America increased, ships were being built especially for passenger traffic;

companies had regularly scheduled sailing dates. After 1840's, trans-oceanic steam powered

ships started to replace the sailing vessels which reduced the travel time from one-or-two months

or more to about two weeks.

Customs Passenger Lists were prepared by the ship's captain and were filed with the collector of

customs at the port of arrival. These lists were initially meant to serve for statistical purposes.

Except for a few ports, most of these passenger lists have survived. Information that may be

found includes:

• Country, province, or exact town of origin (About 10% of the lists may have an exact

town listed)

• Date of arrival in the U. S.

• Family members or others who immigrated on the same ship

• Destination in the U. S.

• Occupation, age, and sex

About 1891 to 1957

In 1892 Congress passed the first federal law regulating immigration followed in 1891 with the

Superintendent of Immigration being established which in 1906 became the Bureau of

Immigration and Naturalization. The records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS)

are called Immigration Passenger Lists. The 1891 list consisted of one page. Further

information was added in following years and the list became two pages in 1906. Information

found on these lists includes:

• Ship's name and date of arrival in America.

• Family members or others who immigrated on the same ship

• If going to join a relative, the relative's name, address, and relationship

• Birthplace (country and city), added in 1906

• Name and address of the alien's nearest relative in the country from which they came

was added in 1907

• Look closely for notes marked on the passenger lists. For example, some annotations

indicate the passenger was naturalized (possibly leading you to find the naturalization

record), other notes indicate they were detained. (Note: The detained passengers with

the reason for detention and including other information are generally listed on the

last sheet of the ship's manifest.) See: "Guide to Interpreting Passenger List

Annotations" http://www.jewishgen.org/InfoFiles/Manifests/

Available Immigration Passenger Lists

The implementation of the new forms depended on many factors, including who was in charge of

the port. Some ports were immediately regulated by federal immigration officials while, for other

ports, federal officials contracted the administration to local officers. Typically any lists created

under the authority of the Immigration Bureau are considered Immigration Passenger Lists, even

though they may have begun at various times.

Although the National Archives has Immigration Passenger Lists for at least thirty-seven

different ports, many of those lists include only a few ships over a few years, such as

Panama City, Florida from 1927 to 1939. Three small Florida ports appear to have lists

for one day only! Virtually all modern immigrants arrived at one of seven different ports,

whose records have been acquired by the National Archives and are available on

19

microfilm. The following table identifies these major ports. Other ports, with significant

Immigration Passenger Lists on microfilm include Key West, FL; Providence, RI.

Immigration Passenger Lists in the National Archives

Ports

Baltimore, MD

Lists

1891-1957

1891-1943

1903-1945

Indexes

1897-1952

1902-1906, 1906-1920,

1899-1940

New Orleans,

LA

1897-1948

1900-1952

New York, NY

1883-1945

1897-1902, 1902-1948

Philadelphia,

PA

1893-1953, 19541957

1883-1948

San Francisco,

CA

1890-1957, 19491954

1893-1934

Boston, MA

Seattle, WA

Un-indexed

How to Use Passenger Lists

You can use ships passenger lists to

• Discover when your ancestor arrived in the U.S.

• Find out which country your ancestor was from

• Learn roughly when he or she was born

• Find the occupation of your ancestor

• Uncover family relationships

• Find evidence of chain migration

• Perhaps find the name of a county, town or place more specific than a country

• Learn the dividing line time-wise of when to focus your research in the U.S. and

when to focus on the country of origin

• Learn marital status

• Learn place of origin in the "old country"

• Find names and addresses of other family members

• Find clues to initial (perhaps temporary) settling places in the U.S.

• Learn of previous stays in the U.S. (leading to other arrival records)

• Determine literacy

• Get a feel for economic status

• Help reconstruct the immigrant journey and experience

• Seek clues for motivation of emigration (e.g., poverty, possibly avoiding draft in

home country, etc.)

• Learn of health problems

• Learn of family members who may have been turned back or who died before

formally entering the U.S. (e.g., at sea or at hospital)

• Learn of ancestors born at sea

• Discover an ancestor's physical appearance

• Learn the birth place

20

•

•

Learn of other places the ancestor may have lived before emigrating

Obtain information to lead to emigration records

Starting Points for Further Research

Starting points for learning more about Passenger Lists on the internet are as follows:

Emigration/Migration Ships and Trails Mailing Lists

http://www.rootsweb.com/~jfuller/gen_mail_emi.html

Immigration and Ships Passenger Lists Research Guide

http://home.att.net/%7Earnielang/shipgide.html

Passenger Lists on the Internet

http://members.aol.com/rprost/passenger.html

Passenger Lists; Ships; Ship Museums

http://www-personal.umich.edu/~cgaunt/pass.html

The Ships Lists

http://www.theshipslist.com/

What Passenger Lists are on line?

http://home.att.net/~wee-monster/onlinelists.html

Immigration and Ships Passenger Lists Research Guide

http://home.att.net/%7Earnielang/ship02_3.html#Introduction

National Archives: Genealogists/Family Historians

http://www.archives.gov/genealogy/index.html

Passport Applications

Passports have been issued since 1789 by the Department of State to U.S. citizens traveling

abroad and passport records for individuals are available from 1795. Foreign born applicants

were required to provide documented proof of naturalization to secure a passport. For children,

the name of the father, his date and place of birth, and naturalization were listed. Passports were

issued for 3 years. (They are now issued for 10 years) Photos have been attached since WWI and

physical descriptions were then added including, height, hair and eye color. Until 1941,

passports were not always required for travel to most foreign countries. Passport applications can

help in locating your ancestral home. Naturalized immigrants may have applied for passports

when they may have returned to visit their native countries. If they did apply for a passport, their

passport records would generally provide information regarding:

• Family status

• Date and place of birth

• Naturalization

• Occupation or business

• Physical characteristics

Starting Points for Further Research

Starting points for learning more about passport applications include:

21

National Archives: Genealogists/Family Historians

http://www.archives.gov/genealogy/index.html

Other Immigration Lists

When our ancestors immigrated to America, especially from Europe, a number of lists were

generated:

• Lists made at the original port of embarkation

• Lists may have been prepared if the ship stopped at another port along the way

• Lists at the port of arrival in the U.S. (Ships Passenger Lists)

• Lists in newspapers tell the ships arriving and departing and type of cargo

• Lists by a sponsoring organization such as (e.g. an emigrant aid society), or if the

ship was quarantined when it arrived in the U.S.

Probate Records

Probate records (i.e., the process of passing that property, both land and various goods, on to

one's heirs) are one of the major types of records used in genealogical research. Heirs may be

anybody the testator (the person who made the will) chooses to name, including servants, in-laws,

friends, and others. Wills and other papers created during the probate process are often the best

possible source to document relationships between family members, particularly parent to child.

Persons often identified themselves according to the place (often a town) they came from, or were

born in. Some (but certainly not all) wills and other probate papers may provide a key link

between an immigrant in the new world and his family in the old. For example:

•

•

American wills may mention a family's origins in the old country

Foreign wills, e.g., British, may bequeath property (goods or money) to relatives who

had emigrated

Many of the colonial probate records up through the early 1800’s have been published.

How to Use Probate Records

Use probate records to

• Find death date and place

• Find residence

• Find names (and addresses) of descendants

• Find details to search for land records

• Discover other places where the ancestor may have held property

• Discover relationships

• Get a feel for ancestor's economic standing

• Look for clues about ancestor's feelings toward family members

• Find clues to the deaths of other family members

• Sort out adoptions, guardianships and other unclear relationships

• Learn names of stores and vendors frequented by your ancestor

• Find your ancestor's signature

• Find occupation

• Find citizenship

• Find marital status

22

Starting Points for Further Research

Starting points for learning more about probate documents include:

Cyndi's List:

www.CyndisList.com/wills.htm

About.com

Wills and probate sites:

genealogy.about.com/hobbies/genealogy/msubwills.htm?rnk=r&terms=wills

To learn more about probate records and how to use them in your research:

Wills and Testaments

By Donna Przecha:

www.genealogy.com/46_donna.html

Where There's a Will, There's a Way

By George G. Morgan:

www.ancestry.com/columns/george/12%2D25%2D98.htm

Land Grants and Transfers

Land records are generally not a preferred source for learning the origins of immigrants. They are

invaluable in other aspects of genealogical research, but seldom mention an immigrant's home.

They also seldom identify that a person was not an immigrant, nor do they usually provide an

age. They are generally best at establishing residency, and relationships. However, in the colonial

time period, land records can sometimes be used to establish immigration.

One of the major factors influencing immigrants to come to America was the availability of land.

Many came for the land and therefore became the first settlers in many areas. Most lists of early

settlers seem to be based on land grants of one kind or another. In some southern states these

settler lists come from headrights, which is documentation of having transported a certain number

of persons to settle on, and improve, various tracts of land.

How to Use Land Records

Use land records to

• Find death date and place

• Find residence

• For names (and addresses) of descendants

• Find details to search for land records

• Discover other places where the ancestor may have held property

• Discover relationships

• Get a feel for ancestor's economic standing

• Look for clues about ancestor's feelings toward family members

• Find clues to the deaths of other family members

• Sort out adoptions, guardianships and other unclear relationships

• Learn names of stores and vendors frequented by your ancestor

• Find your ancestor's signature

23

•

•

•

Find occupation

Find citizenship

Find marital status

Starting Points for Further Research

Starting points for learning more about land records include:

Bureau of Land Management (BLM)

A site with live database access to federal land conveyance records for the public land

states. Includes digital images of more than 2,000,000 federal land title records for

Eastern public land states issued between 1820 and 1908. Images of serial patents, issued

between 1908 and the mid-1960s, are currently being added:

www.glorecords.blm.gov

Analyzing Deeds for Useful Clues

By Elizabeth Shown Mills:

www.bcgcertification.org/skillbuilders/skbld951.html

Linda Haas Davenport's Learning Center - click on land records:

http://homepages.rootsweb.com/~haas/learningcenter.html

U.S. Land & Property Research

By Bill Utterback

http://users.arn.net/~billco/uslpr.htm

Retracing the Trails of Your Ancestors Using Deed Records

By William Dollarhide

www.ultranet.com/%7Edeeds/deeds.htm

Homesteaders Left Marks on Land and Paper

By Myra Vanderpool Gormley

www.ancestry.com/columns/myra/Shaking_Family_Tree07-24-97.htm

Social Security Applications

As a result of the Great Depression that began in 1929 which destroyed the finances of millions

of Americans and created wide-spread suffering, President Franklin D. Roosevelt responded by

working for the passage of the Social Security Act of 1935. In that legislation, employers and

employees were taxed for the purpose of providing old age pensions to workers who reached the

age of sixty-five. In order to get into the program persons were required to complete a short

application form, the SS-5, to receive a Social Security number.

If the person you're searching for was alive and working sometime from 1937 on, there's a good

chance there's an application on file for him (unfortunately, this is a less useful resource for

women until recent decades when virtually everyone started to get a Social Security card).

Because the application was filled out by the person themselves, the information is fairly reliable.

The Social Security application is so valuable because the names of the parents were provided by

the very person being researched. The SS-5 application can be used as a pointer to other sources.

The form included 16 questions which have varied over time and includes the following

information:

24

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Applicant's first, middle and last names

For women, the maiden name or previous married name

Applicant's address

Applicant's employer and employer's address

Applicant's age at last birthday

Applicant's date of birth

Applicant's place of birth

Full name of applicant's father

Full maiden name of applicant's mother

Applicant's gender

Applicant's race

Applicant's signature

Date the application was filled out

It may also include:

• Applicant's work name if different than name above

• Applicant's marital status

• Wife's maiden name if applicant is male

• Beginning or ending date of employment

• How applicant was paid

In order to obtain a copy of an SS-5, you can contact the Social Security Administration. For the

latest instructions and fees go to:

Guide to FOIA Requests

http://www.ssa.gov/foia/html/foia_guide.htm

Or Google: How to Request a Copy of the SS-5

The fee for searching for the SS-5 application when the Social Security number is provided is

$27.00 and $29.00 when a number is not provided, at the time of this writing.

Starting Points for Further Research

Starting points for learning more about social security records include:

Cyndi’s List

http://www.CyndisList.com/socsec.htm

Social Security Death Index

Immigrants are included in the Social Security Death Index (SSDI). SSDI does not include the

names of everyone, even if they had a Social Security number (SNN). If relatives or the funeral

home did not report the death to the Social Security Administration, or if the individual died

before 1962 (when the records were computerized) then they probably will not appear in this

database. The omission of an individual in this index does not indicate the person is still living. It

simply means that there was no report of the person's death to Social Security Administration.

When using the Social Security Death Index, in addition to the date of birth and date of death,

there are three possible places included as well:

25

•

•

•

State of issuance (where a person then lived and applied or the state in which the office

that issued their social security number was located).

Residence at time of death (this is really the address of record, but not necessarily where

they lived or died).

Death benefit (where the lump sum death benefit [burial allowance] was sent).

Starting Points for Further Research

Starting points for learning more about social security records include:

Cyndi’s List

http://www.CyndisList.com/socsec.htm

Rootsweb.com

http://rootsweb.com/

Societies

Lineage/Hereditary Societies

A lineage society is an organization whose membership is limited to persons who can prove

lineal, documented, or descent from a qualifying ancestor. Hundreds of such organizations exist

in America, such as who fought in the American Revolutionary War (Daughters of the American

Revolution, DAR), who came as Mormon Pioneers (Daughters of the Utah Pioneers, DUP), or

those who arrived on the Mayflower.

Many lineage societies publish books of interest to their members, and of interest to other

researchers. These books are found in most major genealogical libraries and can help you

determine if a society might have information about a possible ancestor. A good resource to

identify such societies includes:

Hereditary Society Blue Book

http://members.tripod.com/~Historic_Trust/society.htm

Immigrant and Early Settler Societies

Dozens of societies have been established focusing on specific immigrant groups, or early settlers

of some locality. While these societies have an interest in immigrants, they do not always know

where any particular immigrant came from in the old country. Their objectives do not include

establishing the immigrant or settler's ancestry, only their descent to current persons. Examples

of these societies include:

•

•

•

•

Society of the Descendants of the Founders of Hartford (Connecticut), which requires the

ancestor be living in Hartford by early 1640.

Order of Descendants of Ancient Planters, those persons who arrived in Virginia before

1616.

General Society of Mayflower Descendants, descendants of the Mayflower passengers.

The Order of the Founders and Patriots of America, (pre-1657) founders who established

families in America, among whose descendants, of the same surname line, were persons

who fought for American independence in the Revolutionary War.

Some examples of immigration collections include:

26

•

•

The Balch Institute for Ethnic Studies at Temple University in Philadelphia in

transcribing many of the passenger arrival lists of ethnic immigrants.

The Immigration History Society at the University of Minnesota has collected thousands

of ethnic newspapers and other sources dealing with eastern European ethnic groups.

Their "Immigration History Research Center" is one of the most significant repositories

of research materials for those groups in North America.

European Ancestry Societies

Some lineage societies focus on ancestors who were notable long before the American colonies

were established. Therefore, descendants who wish to join need to trace their ancestry back to the

immigrant (called the "gateway" ancestor), and then trace that immigrant's ancestry back to the

qualifying ancestor in the old country. Usually the qualifying ancestor was part of British royalty

or nobility. Examples include:

•

•

Order of the Crown of Charlemagne in the United States of America, which requires

documented descent from that early emperor. This means tracing your ancestry back

more than 1,000 years.

Descendants of the Illegitimate Sons and Daughters of the Kings of Britain.

Nationality or Ethnic Lineage Societies

These are societies that focus on an entire ethnic group. They gather information, teach their

members, and publish stories, findings, and sources, about that group. A small number of such

societies, and actually the oldest such societies in America, are true lineage societies.

Membership is limited to those persons who can prove descent from an early settler of a specific

ethnic group. Examples include:

• Dutch in New York,

• Germans in Pennsylvania

• Scots-Irish in the Carolinas

Genealogical Societies

Genealogical societies exist throughout the United States and Canada in every state or province,

most counties and many major cities. The people in these societies share the same interest you do:

individually discovering a heritage. They gather together, usually monthly, to learn from each

other about how to trace their ancestry. They recognize that together they are much more

knowledgeable about the ins and outs of family history research than they are individually.

Society Publications

Society publications can be a significant aspect of immigrant research. Any local record may be

the subject of publication by a local society. Whenever you contact a genealogical or ethnic

society, be certain to inquire about their publications. Even when such publications do not

identify an immigrant's home town, they may provide further identification about your

immigrant, or may instruct you on additional sources specific to a locality or ethnic group.

Starting Points for Further Research

Starting points for learning more about or finding societies include:

Cyndi's List of societies and groups

Ethnic, lineage, national, etc.

http://www.CyndisList.com/society.htm

27

Cyndi's List of state resources

Look under your state of interest and select "societies and groups.”

http://www.CyndisList.com/usa.htm

Genealogical Societies

To locate societies in a specific area or for more information about genealogical societies

in general, contact the Federation of Genealogical Societies (FGS). This is an umbrella

organization of more than 525 genealogical groups throughout North America.

Federation of Genealogical Societies

P.O. Box 200940

Austin, TX 78720-0940

Phone: 512-336-2731

Fax: 512-336-2732

E-mail: fgs-office@fgs.org

Military Records

For immigrants in all time periods, military records are very important because they often ask the

soldier's birth place and birth date or age at enlistment. Records exist for many of the military

engagements taken by the United States from the Revolutionary war forward. There are 3 types

of military records: Service Records, Pension Records and History Records.

The most important for immigration records are Enlistment/Discharge and Pension Records. The

following is an overview of the three types of records.

The records that are important for immigration include:

Service Records

Service records cover the time an ancestor was actually in the service. These records almost

always include:

• Name

• Dates of enlistment, attendance, and discharge

• Beginning and ending rank

• Military unit

And they may include:

• Date and/or place of birth

• Age

• Physical description

• Occupation

• Citizenship

• Residence

• Mentions of injuries or illnesses

• Reference to time as a POW

• Date and/or cause of death

• Cemetery of burial

28

How to Use Service Records

Use service records to

• Learn about an ancestor's military service

• Find the necessary details to locate a pension file or military history

• Learn place and/or date of birth

• Learn other details such as residence, occupation or citizenship

• Find a physical description

• Find death and/or burial information

• Find medical information

• Find insights into ancestor's personality and performance (e.g., promotions, AWOL

notations, etc.)

• See if and where held as a POW

Pension Records

Pension records cover the post-service period when your ancestor (or their next-of-kin) may have

received benefits. They usually include:

• Name

• Dates of enlistment and discharge

• Beginning and ending rank

• Military unit

They may include

• Date and/or place of birth

• Physical description

• Occupation

• Citizenship

• Residence

• Marital status

• Name of spouse

• Names (and possibly birthdates) of children

• Marriage date and details

• Names of parents

• Affidavits by friends, associates and others

• Letters written by the veteran, his kin, or his attorneys

• Signature

• Medical examination findings

• Date and/or cause of death

• Cemetery of burial

• Photo or sketch

How to Use Pension Records

Use pension records to

• Learn about an ancestor's military service

• Find the necessary details to locate a military history

• Learn place and/or date of birth

• Learn of dates and places of other life events

• Learn names of spouse and/or children, as well as their birth dates

29

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Learn other details such as residence, occupation or citizenship

Find a physical description

Find death and/or burial information

Find medical information

Learn insights into ancestor's personality and performance (e.g., through his letters,

affidavits files by others who knew him, etc.)

Learn of ancestor's literacy

See ancestor's signature

Learn more about ancestor's post-war years and life

See what he looked like

Military History

Military histories (often referred to as regimental or unit histories) can add historical background

to help you understand the conflict and your ancestor's participation in it. They usually include:

• Roster of those who served in the unit

• Dates of major engagements

May also include:

• Descriptions of battles

• Personal details about individuals, especially officers

• References to personal diaries and letters of those who served in the unit

• Photos of those who served

How to Use Military History Records

Use military history records to

• More fully appreciate the military experience of your ancestor

• Learn who he served with

• Learn which engagements he was involved in

• See what he looked like

Starting Points for Further Research

Starting points for learning more about military records include:

How-to Guides, Research Outline for U.S. Military Records

www.familysearch.org/sg/Military.html

RootsWeb's Guide to Tracing Family Trees - U.S. Military Record

www.rootsweb.com/~rwguide/lesson14.htm

In Search of Military Records

By Ken Short

www.iigs.org/newsletter/9807news/military.htm.en

Military Records: History of and How to Use Them

By Linda Haas Davenport

http://homepages.rootsweb.com/~haas/learningcenter/military.html

Cyndi's List of U.S. Military Resources

Including links by conflict, mailing lists, researchers, and more:

www.CyndisList.com/military.htm

30

Cyndi's List of lineage societies and groups with a military focus:

www.CyndisList.com/military.htm#Societies

NARA's links

Official organizations that can provide historical information such as unit histories,

personal papers, and photographs:

http://www.archives.gov/publications/by_organization.html

About.com military resources

http://genealogy.about.com/od/military_records/

Lineages, Inc.'s Military Research Room

An online resource with historical information and research tips, broken down by

conflict:

www.lineages.com/military/default.asp

Military record indexes on CD

(Mostly Civil and Revolutionary Wars)

www.familytreemaker.com/backissu.html

Resources Specific to Military Conflicts

http://www.usigs.org/library/military/

Cemeteries

Cemetery records have their own limitations as sources for immigration information. While it is

not common for a foreign birth town to appear on a cemetery headstone, there are literally

thousands of cases where such is the case. Such circumstances seem to be more common where

there are many immigrants in a cemetery, such as in Pennsylvania German communities or the

cemeteries by the Catholic missions in California.

While locating a burial site can be difficult. People are usually buried where they die. Begin

your search for a cemetery where your ancestor “drops” out of the records.

In any given area, there are usually many cemeteries which include all or most of the types listed

below. The records of these various cemeteries are often in many different places, and not easily

accessible. The records are often organized in chronological order or by plot, and therefore, not

alphabetical. If public records exist for your ancestor, they will usually denote where the burial

occurred. For deaths occurring after 1870, the community may have required a burial permit

from the local health department (these are not death certificates) and identify the cemetery.

There are many directories to assist you in locating a specific cemetery, or even a list of all

possible cemeteries in a certain locality. In large cities, begin with the city directory for the time

period when the immigrant died. Directories include:

•

•

•

Cemeteries of the U.S.

United States Cemetery Address Book

The Geographic Names Information System (GNIS)

Nation's official repository of domestic geographic names information including

cemeteries.

31

http://mapping.usgs.gov/www/gnis/gnisform.html

If you still have trouble locating the cemetery, you may want to check current directories of

mortuaries (available from your local mortician). A local mortuary in the area where an

immigrant died, will be aware of at least the active cemeteries, and may be able to refer you to a

local cemetery association. Once you have located the cemetery, you will seek the following

information:

•

The inscription on the stone.

Tombstone inscriptions are as different as the individuals they commemorate. In most

cases you will find some element of value. For example, a tombstone can show a

relationship with an inscription "Beloved wife of . . .". You will find logos or markers

that indicate service in the military or organization. Depending on the area of the

country and era, you will find a birth place such as immigrant rich communities. Some

tombstones contain photos, favorite saying, writings, music, or images that relate to a

hobby or profession. Tombstones can also carry lineage such as names of the children or

“Daughter of….”. You will most like find the true given name of the person or even a

nick name that can help you find information.

•

The records of the sexton.

Note: Many cemeteries have paper records of persons who are buried there which are

kept with the sexton. These records come in many formats. They usually include the

name of the person buried, death date, and owner of the cemetery plot. The first place to

find sexton's records is the cemetery itself. If you come across a cemetery that is

“inactive” or “full” because there is no more room for additional burials, contact the local

sexton to begin your search to see if they have records.

When you combine the tombstone and sexton’s record, you can build a profile that

unusually include:

o Name of deceased (Tombstone and Sexton Record)

o Years of birth and/or death (Tombstone)

o Date of burial (Sexton Record)

•

May also include:

o Address of deceased (Sexton Record)

o Age of death (Tombstone and Sexton Record)

o Birthplace (Tombstone)

o Cause of death (Tombstone and Sexton Record)

o Cost of the plot and/or burial (Sexton Record)

o Date of death (Tombstone and Sexton Record)

o Full name, including maiden name for women (Tombstone and Sexton Record)

o Full dates of birth and/or death (Tombstone and Sexton Record)

o Information linking the plot owner to other plots (e.g., disinterment, reburial,

etc.) (Sexton Record)

o Information about military service, such as unit (Tombstone)

o Inscription (e.g., poem, Bible quote) providing insight into the ancestor or those

left behind (Tombstone)

o Logo of organization deceased belonged to (ethnic, religious, military, etc.)

o Name of doctor and/or hospital (Sexton Record)

o Name of officiating minister (Sexton Record)

o Names of other involved - funeral home, officiating clergyman, memorial

company (Sexton Record)

32

o

o

o

o

Owner of the plot (Sexton Record)

Relationship Clues ("Beloved wife of...) or (Who else is buried in plot)

(Tombstone and Sexton Record)

Marriage date (rare) (Tombstone and Sexton Record)

Where deceased died, if other than where he/she lived (Sexton Record)

The four types of cemeteries include:

Religious Cemeteries. Religiously devout immigrant ancestors were most often buried

in religious cemeteries. These cemeteries were often located next to the group’s church

or synagogue. Qualification for burial was often reserved for burial of the faithful (and

sometimes not so faithful). For some religions, notably the Roman Catholic, burial in

sacred, consecrated, ground was essential to a person's salvation. For many others, burial

was a sacrament, to be conducted by a spiritual leader. If a church conducted a burial, the

most convenient place of interment would be the local church yard. The records of

burials in religious cemeteries are most likely to be found with that religious group.

Records of these burials are usually found with church and not with a sexton.

Community Cemeteries. Most of our immigrant ancestors during the 1800’s were

buried in cemeteries established by a local community (i.e., city, town, township, or