Writing competitive proposals: How to proceed in FP7 Building and Managing

Day 1:

Writing competitive proposals:

How to proceed in FP7

Day 2:

Building and Managing

a successful consortium

Contact Details:

Lotte Jaspers

jaspers@yellowresearch.nl

Mette Skraastad

skraastad@yellowresearch.nl

Course 18 and 19 December Bilbao:

CONTENTS

Chapter 1

Handout Presentation Day 1:

Writing Competitive Proposal:

How to succeed in FP7’

Chapter 2

Handout Presentation Day 2:

Building and Managing

A Successful Consortium

Chapter 3

Guide - Handling the EU evaluation criteria:

Impact and implementation

Chapter 4

Gantt and Pert Charts

Chapter 5

Checklist for researchers: How to start?

CHAPTER 1

Competitive Proposals

How to succeed in FP7

1

Presenters yellowresearch.nl

Lotte Jaspers:

Mette Skraastad:

jaspers@yellowresearch.nl

skraastad@yellowresearch.nl

+31-20-422.1115

+31-20-422.1801

In co-development with Richard Tomlin,

Bluebell Research

22

Programme

Part I

Part II

FP7 structure

Writing Your FP7 Proposal

z

Part III

Part VI

Exploitation

Effective dissemination plans

z

Part V

Proposal structure

z

Part VI

Part VII

Project budgeting

FP7 agreements

z

z

z

z

33

1

Part I: FP7 structure

4

Relationships legal and other texts

TREATY

TREATY

FRAMEWORK PROGRAMME

FRAMEWORK PROGRAMME

RULES for PARTICIPATION

RULES for PARTICIPATION

Negotiation

Negotiation

Guidance

Notes

Guidance Notes

SPECIFIC PROGRAMMES

SPECIFIC PROGRAMMES

Rules for

Rules for

evaluation

evaluation

Guide to IP

Guide to IP

rules

rules

EC – Grant

EC – Grant

Agreement

Agreement

Guides for

Guides for

applicants

applicants

WORK PROGRAMMES

WORK PROGRAMMES

Call

Call

Guide to fin.

Guide to fin.

issues

issues

Consortium

Consortium

Agreement

Agreement

Checklist for a

Checklist for a

CA

CA

55

EU Framework Programmes

60

€ Billion

50,5

50

40

30

17,5

14,96

20

10

3,27

5,36

6,6

13,12

0

(FP1)

FP2

FP3

FP4

Cooperation

FP5

Coor.

FP6

FP7

Integr.

Comp.

66

2

Diagram of FP 7

Cooperation

Ideas

People

Initial training

1. Health

2. Food, Agr.

Biotech.

Life long

training

IndustryAcademia

International

dimension

3. ICT

4. Nano

5. Energy

ERA-NET

6. Environment

7. Transport

8. Socio-econ

9 Space

10 Security

Capacities

Research

Infrastructures

Research for

benefit of SMEs

Regions of

knowledge

Research

potential

Science in

society

International

cooperation

JRC

Prosperity

Solidarity

Security and

freedom

Europe as

world partner

Emerging needs

International

cooperation

JTI

77

Technology

platforms

Budget breakdown

Cooperation

Ideas

People

Capacities

JRC

88

Cooperation budget breakdown

Health

KBBE

ICT

NMP

Enery

Environment

Transport

SSH

Space

Security

99

3

Policy Background FP7

The overriding aim for FP7 is to become the world's leading

research area by establishing excellent research projects and

networks

2000 - Lisbon:

European Research Area (ERA)

2001 - Stockholm: Stimulating jobs

2002 - Gothenburg: Entrepreneurship and a well-functioning

internal market as key to growth and job

creation.

2002- Barcelona:

The Sustainable Development Strategy.

2005

The renewed EU Sustainable Development

Strategy.

2005

Renewed Lisbon Partnership for Growth &

Jobs

2007

Green Paper the European Research Area:

New Perspectives

10

10

Employment

Full employment

Sustained growth

Lisbon

Innovation

Stockholm

Knowledge

Gothenburg

Competitiveness

Barcelona

Economic

sustainibility

The EU policies

11

11

Research charter

z

z

z

z

z

Enlargement of research employability

Voluntary basis

27 countries have undersigned the Charter

Perhaps a regulation

DG mobility passport (track record for pensions etc)

12

12

4

Influencing calls

z

European Commission

z

European Commission

z

Programme Committee

members

z

Expert groups

z

Stakeholders

z

Interest groups

z

Call for interest

z

Programme Committee

13

13

FP7 Specific Programmes

Activities:

Funding Schemes:

Cooperation

z

z

z

Collaborative Research: Large Scale IP

and Small/Medium Scaled Focussed

Projects (including specific groups),

Network of Excellence,

Coordination and Support Actions.

Ideas

European Research Council

People

Marie Curie

Capacities

Research Capacities

14

14

Relevance

to the

Programme

Potential

Impact

&

S&T

Excellence

&

3

Consortium

Quality

&

4

3

Management

Quality

&

3

Mobilisation

of

Resources

&

3

3

FP6 = Maximum 30 and a Threshold of 19

Impact

Relevance

Science & Technology

Relevance

3-4

&

3-4

Implementation

Quality & efficiency

&

3-4

FP7 = Maximum 15 and a Threshold of 10 to 12

15

15

5

Evaluation criteria Cooperation

z

Scientific and/or technological excellence + Relevance

z

The potential impact through the development,

dissemination and use of project results + Relevance

z

Quality and efficiency of the implementation and

management

The workprogramme may specify and add

additional requirements, weightings and tresholds

16

16

Selection criteria ICT and NMP

z

Quality of science and technology

● Soundness of concept and quality objectives

● Contribution to knowledge

● Quality and effectiveness workplan

z

Impact of project

● Contribution to EU challenges

● Measures for dissemination and/or exploitation

● Broader beneficial impacts (large scale)

z

Implementation

● Management structures and procedures

● Quality of consortium and balance

● Quality and expertise of individuals

● Resources allocation and justification

17

17

Gender aspects (Part B4)

z

When addressed in the call, gender might be an

evaluation criterion which is assessed and negotiated by

the EC

z

Good to include anyway

z

Practical actions:

●

●

●

●

Collect gender statics

Establish Gender Awareness Group

Organise outreach activities

Create incentives

18

18

6

Ethics (Part B5)

RESEARCH INVOLVING:

Human beings, -biological material,

-embryo's & -genetic information

RESEARCH FIELD

Medical Research

Personal data including data about

a person's health, sexual lifestyle,

ethnicity, etc.

Animals

Social sciences (questionnaires),

medical research

Developing countries

Social Sciences other………….

Plants

Food and Agriculture.

Dual use

Security and Space.

Medical, Veterinarian, biology and

some social sciences

19

19

Evaluation score values

z

0 - The proposal fails to address the criterion under examination or cannot

be judged due to missing or incomplete information

z

1 - Very poor. The criterion is addressed in a cursory and unsatisfactory

manner.

z

2 - Poor. There are serious inherent weaknesses in relation to the criterion

in question.

z

3 - Fair. While the proposal broadly addresses the criterion, there are

significant weaknesses that would need correcting.

z

4 - Good. The proposal addresses the criterion well, although certain

improvements are possible.

z

5 - Excellent. The proposal successfully addresses all relevant aspects of

the criterion in question. Any shortcomings are minor.

20

20

Evaluation procedure – step 1

z

3 evaluators per proposal (5 for NoE)

z

Briefing by EC

z

Evaluation in Brussels or remote

z

Each evaluator gives scores and comments for each criterion

z

Each evaluator indicates whether the proposal falls

● inside the scope of the call,

● deals with sensitive ethical issues or/and security considerations

Æ Outcome Individual Assessment

21

21

7

Evaluation procedure – step 2

The next phase is to reach consensus, based on the individual

assessments

z

Consensus meeting (in Brussels or electronic) to discuss scores and

comments

z

EC appoints rapporteur

z

EC is monitor

Æ Outcome Consensus Report with scores and comments

22

22

Evaluation procedure – step 3

Review panels have the tasks:

z

To examine the consensus reports, to check consistency of scores,

and, where necessary, to propose a new set of scores.

z

If applicable,

● Hearings with the applicants;

● Resolving cases with a minority view;

● Recommending a priority order for proposals with the same

score;

● Making recommendations on possible clustering or combination

Æ Outcome Evaluation Summary Report and listings with priority

23

23

Part II: Writing Your FP7 Proposal

24

8

Exploration phase:

Is FP7 the right instrument ?

z

National Funding

z

Charities, national or international

z

EU: Marie Curie, European Research Council

z

Industry

Be honest and dare to abandon an idea

25

25

How to write a proposal

z

Call Fiche

z

List of Topics, Funding Schemes, Deadline

and budget, evaluation procedure and

timeline, minimum conditions (number of

partners)

z

Workprogramme

z

Policy context, approach, other activities,

content of calls (description area and topics)

and call fiche

z

Guide

z

Description funding scheme, how to apply,

check list, administrative procedure, glossary,

timetable, evaluation criteria and procedure,

instructions part A and part B

http://cordis.europa.eu/fp7/home_en.html

26

26

Part III – Exploitation strategies

27

9

Proposal Writing is an incremental process and needs Business Development

expertise

Impact

Relevance

Science & Technology

Relevance

B1

&

Implementation

Quality & efficiency

&

B3

B2

28

28

FP7

Core Proposal Structure

z

B1 – Scientific and/or technical quality (concept and objectives, progress,

workplan including work packages, deliverables and milestones)

z

B2 – Implementation (management structure, individuals, consortium, resources)

z

B3 – Impact (expected impact, D&E plan, management IPR)

z

B4 – Ethical issues (if applicable)

z

B5 – Gender

29

29

B1-Deliverables could be anything

Data or Human Material

Publications, Repositories

Software: Technical, Business,

Application

License, Open Source Public domain

Policy Recommendations:

Workshops, websites

Some forms of

Project Results

Inventions (New matter

or new process) : License / sale

Database and Repositories:

Research Tool

30

30

10

B3-Use

GA: II-1.8

z

Further research

z

Exploitation (direct or indirect):

● Product or process

● Service

z

For every result the possible use and exploitation route

need to be considered.

31

31

B3-Results

z

Deliverables, those tangible results necessary to fullfill your

contractual obligation to the commission during the duration of the

project.

z

Results could be the deliverables or other tangible results of the

project and need to be addressed in the Dissemination and Use plan

32

32

B1-Deliverables and milestones

z

Deliverable is a tangible result: a concrete output and

evidence of the work .

The nature of the deliverable may be a report, product,

patent, prototype etc.

z

Milestone is a point in time. A control point at which a

decision is needed.

Example: adoption of a technology as a basis for the next

phase of the project

33

33

11

B1 - Objectives

Demonstrate impact through addressing one or more topics (the EU

challenges) described in Specific and Work Programmes in a

measurable and verifiable way.

The topics are EU challenges, not national challenges, only achievable

by:

● Pooling European resources

● Comparative research

● Standardisation

34

34

Concepts

•

•

Value model

1 invention

► 1 product

► 1-3 licensees

•

•

Open innovation

100-1000 inventions

► 1 product

► 10-100 licensees

35

35

Development drug

value model

Chemistry

COSTS

10,000 compounds

Pharmacology and safety assessment

100 compounds

Clinical phase

10 compounds

Market

1 compound

36

36

12

Development consumer electronics

Open Innovation

Research

1 invention

Development

10 ideas

Prototype

COSTS

1000 prototypes

Market

500-2000 products

37

37

Public domain

z

No IP protection

● ‘No market’

● No tool to detect breach of patent right

● For specific sector

z

Free for everyone to be used for further research and/or exploitation

z

Examples: material, research tools etc

38

38

‘Open Source’

z

License is freely obtained, provided improvements are

made available to all

z

Right to file patent on products

39

39

13

Part IV - Dissemination

40

What is Dissemination

z

Spread and transfer of knowledge –

z

in multiple forms and via multiple mediums.

41

41

Use (exploitation)

Dissemination

Societal engaged

actors:

Exploitation

Stakeholders:

Target

Audiences:

- Experts (peers)

- Business sector

- Academics

- Information providers

- Information

- Public Sector

- Public, societal actors

providers

Science & Tech

- End-users

- End-users

- Public

- Other sectors

42

42

14

Dissemination Objectives

1.

Awareness raising

2.

Interest raising or Persuasion about the relevance and applicability

of something (the impact)

3.

State of the Art – the more traditional tools of the academic

community

4.

Decision- tools that provide in depth understanding of the project or

innovation

5.

Action or Sustaining the changed practice

Jeffrey Froyd, Texas A&M University, 2001

43

43

Effective dissemination

z

Needs careful planning which ensures that activities:

● Feed into objectives

● Create the desired impact

● are timely and comprehensive

z

Is far more than the traditional academic dissemination of the results

to their peers or exploitation of results as is common practice for the

business sector.

z

Must be an integral part of your project and can be either a separate

work package or be combined with Use.

44

44

Dissemination strategy

State of

the art

Decision

Action: using

Tools: Results

Awareness

Interest

Strategy

45

45

15

Tools

Example of tools per objective

Awareness

Interest

State-of-theArt

Decision

Action-Using

1-page

summary

Longer

summaries

Publications

2-4 hrs

workshops

1-2 day

workshops

Flyers

Multi-media

tools; CD-roms

Conference

publications

CD-rom

containing

entire web-site

Course

manuscripts

Short films

Website

containing

project

descriptions,

instructional

materials,

assessment

and results

Brochures

Project

descriptions

Sample lessons

46

46

Simple Dissemination Plan

z

Who are the Target Audiences

z

What is the content (message) to be disseminated per target

audience and in what form (type or result)

z

How, through which medium or media is the message disseminated

z

When has the dissemination action to take place

47

47

Elaborate Dissemination Plan adds:

1.

Goals

1.

Access

2.

Objectives

2.

Availability

3.

Source

4.

Success

5.

Barriers

6.

Sustainability

48

48

16

Target Audience

1. Academic users ( i.e. Educational/ research Institutions,

Corporate/ research Universities)

2. Business sector (i.e. Large Companies, SMEs or SME

Networks)

Networks

3. Public Sector (i.e. Public Sector Organisations)

4. SemiSemi- public sector (i.e. workers unions…

unions…..

5. Market specific sectors for example: cultural sector,

Edutainment Industry etc

6. Public in general

49

49

Goals

Key Goal:

Ensure that generated knowledge is used.

The target audience must be able to reach decisions,

learn from experience, and take specific actions to use

the knowledge

50

50

OBJECTIVES – India Reach Project

1.

Collaborate to share good practices and exchange knowledge and

tools

2.

Impact on policy, through advocacy and awareness campaigns

(including forums, networks, website discussions, action research

etc)

3.

Raising community and public awareness about EFA and UEE

Goals.

4.

Individual objectives per partner, that may be more specific for

example raising funds etc.

51

51

17

How and what to disseminate

z

Same objective may require different approaches

(mediums) and content depending on target audience

(since audiences differ in needs, exposure, socio-cultural patterns etc.)

52

52

SAMPLE MATRIX

Target Audience

Objectives

Tools

Media and their

Enablers

Timeline

Academics:

- Researchers

- PhD students

State-of-the-art

Action-Using

Scientific

publications;

Methods,

techniques

Publishers Journals;

Teaching

materials, SOPs

End of Project

Public Sector

users:

-

Awareness;

Interest; Decision;

Action-using

Film, video

Broadcasters, film

distributors

53

53

Overcoming Barriers

z

Language

z

Contextualised situations

z

Localised media

z

Presentation is attractive and sensitive to regional/local

sentiments

54

54

18

Tools/results and IPR protection

z

Most results of dissemination activities will be subject to

copyright, some might be subject to database protection

rights

z

You need to consider what you personally want to do

with the results and what the ‘public’ use is going to be.

55

55

Personal Benefit for a researcher

z

The right to publish results in peer reviewed journals.

z

The right to present results on a congress or in a

meeting.

z

The right to use the results for further research,

preferable world wide.

56

56

From Dissemination to Use

z

Tools/results developed to raise awareness or to be

used in the action stage may have a (commercial) value

as well

z

the short films about medical research projects made for

secondary eduction, may be of interest to broadcast

stations for their educational shows………

57

57

19

To summarise:

Key Elements:

z

Outline your dissemination objectives (based on needs

assessment of target audience)

z

Based on your objectives, plot out a matrix that maps

specific approaches (or communication channels) for the

target audience and identify the enablers to reach to

target audience

z

Matrix should be a comprehensive tool for

implementation with timelines.

58

58

Helpfull websites

GOOGLE!

z

Openaccess-berlin

z

RUSH

z

CHSRF

z

Athenaweb (audiovisual communication of european research)

z

European Research - A guide to successful

communication

=> “dissemination plan”, “dissemination plan ppt”

59

59

Part V – Project Plan

60

20

Proposal Part B-1

z

Concept and objectives

● Explain your concept

● Describe in detail the S&T objectives

z

Progress beyond the state of the art

z

S/T methodology and associated workplan

● Describe the strategy

● Show the timing of WPs and tasks (e.g. Gantt chart)

● Provide a description of work packages

● Summary effort table

● List of milestones

● Provide a Pert diagram or similar

61

61

FP7 proposal structure

EPSS – electronic proposal submission system

62

62

Work package description

W ork package no.

W ork package title

Activity type

Partic. No.

Partic. Short nam e

Start date or starting event

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

Person-m onths per

partic.

Objectives

Description of work (possibly broken down into tasks), and role of

participants

Deliverables (brief description and month of delivery)

63

63

21

B1 – Work packages

z

Type and number of work packages

z

Interactions and dependencies causes by deadlines of

Deliverables and accompanying Milestones

64

64

B1 – Number of WPs

z

RTD and Demonstration:

● Logical clustering of work

● Greater # of partners require greater clustering skills

z

1 WP for management

z

1 WP for Dissemination & Use

z

Other: e.g. Gender and/or ethical?

65

65

How to write a work package

Element

Description

Objective

Describe the outcome of the activity. For example: To set up

a central repository with high quality material of 10.000

patients from three different countries in 1 year time for

proteomics research. To harmonise the clinical data of these

patients in 1,5 year. To obtain informed consent from all

patients within 1 year time.

Description of work

Describe the tasks. The samples will be collected in 3 months

time. For this purpose a material transfer agreement

between the providers Partner 2, 3 and 7 and recipient

Partner 4 will be signed

Deliverables

Describe deliverables and milestones. M1 = Collection of

10.000 samples. D1 = report on the sample collection. D2 =

Database with harmonised data. D3 = Report on the

repository

66

66

22

List of deliverables

Del no

Deliverable name

WP no

Nature

Dissemination level

R = report

PU = public

P = Prototype

PP = restricted to

partners

D = Demonstrator

RE = restricted to a

specific group

O = Other

CO = confidential

Delivery Date

67

67

List of milestones

Milestone no

Milestone name

WPs involved

Expected Date

Means of verification

E.g. Lab prototype

completed and

running flawless

Softeware released and

validated by a user

group

68

68

Part V – Project Costing

69

23

Eligible Costs

Art. II-14

z

Actual

z

Incurred by the beneficiary during the project (except reporting

costs)

z

Determined according to usual accounting and management

principles/practices

z

Used only to achieve project objectives consistent with principles of

economy, efficiency and effectiveness

z

Recorded in accounts (or the accounts of third parties)

z

Indicated in the estimated overall budget in Annex I

70

70

Non-eligible Costs

Art. II-14.3

z

Identifiable indirect taxes including V.A.T.

z

Duties

z

Interest owed

z

Provisions for possible future losses or charges

z

Exchange losses, cost related to return on capital

z

Costs declared or incurred, or reimbursed in respect to another

Community project

z

Debt and debt service charges, excessive or reckless expenditure

71

71

Proposal preparation

z

Coordinator assembles and submits the proposal

z

Partners provide information for section A3:

● Their method of calculating indirect costs

● For each Activity:

• Personnel costs

• Sub-contracts

• Other direct costs (This is where you put the audit costs from the

management section)

• Indirect costs

● Total requested Community contribution

72

72

24

Coordinator: Postman and Banker ?

Art. II.2.3

z

Administer, keep record of Community financial contribution and

inform Commission

z

Distribution of pre-financing/payments in accordance with

Consortium decisions

z

Review the financial statements to verify consistency with the project

tasks before transmitting them to the Commission;

z

Monitor the compliance by beneficiaries with their obligations under

this Grant Agreement.

73

73

Beneficiary Responsibilities

Art. II-3.4

z

To maintain proper records

z

To prepare and submit Financial Statements and

Certificates

z

To agree financial arrangements with Consortium re.

pre-financing and cost limits

z

To carry out the work of the project

74

74

The FP7 Cost Model

One cost model for all applicants:

● Real direct and indirect costs on beneficiary’s

‘normal’ management and accounting principles

● Can be combined with a flat rate for indirect costs

● Provision to combine with lump sums and other flat

rates in the future

75

75

25

Costs categories to be calculated

As in FP6:

z

Direct eligible costs – temporary researchers, consumables, minor

equipment purchases, technical infrastructure and travel and

subsistence.

New in FP7:

z

Time of permanent researchers.

z

Indirect costs: real indirect or flat rate

76

76

Reimbursement rates

Collaborative research

Entity Type

Direct Elig.

Costs

Indirect Elig. Costs

Non profit

75%

75% of real indirect

costs or of flat rate

SME

75%

75%

Others

50%

50%

77

77

Reimbursement rates

Collaborative Projects

Activities

Direct Elig.

Costs

Indirect Elig.

Costs

RTD

50% or 75%

50% or 75%

Demonstration

50%

50%

Other(dissemination,

networking,

coordination, IP,

studies, promotion,

certificates, training.

100%

100%

Management

100%

100%

78

78

26

One activity per work package

z

RTD = Research and technological development (including any

activities to prepare for the dissemination and/or exploitation of

project results, and coordination activities);

z

DEM = Demonstration;

z

MGT = Management of the consortium;

z

OTHER = Other specific activities, if applicable (training, networking

etc).

79

79

Management

Art. II-16.5

No longer limited to 7% (but justify when more)

z

Management activities include:

● the maintenance of the consortium agreement, if it is obligatory

● the overall legal, ethical, financial and administrative management

including all types of required certificates

● the implementation of competitive calls for new participants

● any other management activities foreseen in the proposal except

coordination of research and technological development activities

80

80

Part VII - FP7 Agreements

81

27

Terminology changes

•

Contract

Grant Agreement

•

Contractor

Beneficiary

•

Proposor

Applicant

•

Instrument

Funding Scheme

•

Financial guideline

Financial Rules

•

Audit Certificate

Certificate on FS

•

INCO

ICPC

•

Knowledge

Foreground

•

PEKH

Background

82

82

Diagram of FP 7

and the main Grant Agreement

Cooperation:

MGA

Ideas

People

Capacities

JRC

Core Agreement

III – Infrastructures

II – General

conditions

III –

III – SME actions

III – Civil

Society Org.

IV – Accession

V – Accession

new beneficiary

VI – Form C

VII – Form D

III - ERA-NET plus

VII – Form E

Special clauses

83

83

Collaborative Grant Agreement

Guide: 1.0

•

GA

•

CA

B

B

B

P

B

B

C

P

B

B

P

P

P

P

P

B

P

84

84

28

Development of FP7 CA-s

Guide: 1.1

DESCA

DESCAFP7

FP7

IPCA

IPCAFP7

FP7

IPCA

IPCAFP6

FP6

FP6

FP6Network

NetworkofofExcellence

ExcellenceConsortium

ConsortiumAgreement

Agreement

Collective

CollectiveFP6

FP6Consortium

ConsortiumAgreement

AgreementMemory

Memory

EICTA/UNIT

EICTA/UNIT

EE

ANRT

ANRT

Fr.

Fr.Res.

Res.Org.

Org.

HELMHOLZ

HELMHOLZ

UNITE

UNITE

85

85

Minimum conditions for participation

z

In general 3 independent legal entities from 3 different

Member States (MS) or Associated Countries (AC)

z

Additional conditions can be established by the specific

programme and work programme (i.e. number of

participants, place of establishment, type of participant)

z

Deadline, funding scheme and maximum requested EU

budget

86

86

Definitions

GA: II-1

Background: all IPR/information generated before the

project which is needed

Foreground: all results from the project

Sideground (IPCA): all IPR/information generated during

the project but not resulting therefrom, limited to scope

87

87

29

Definitions: Background

GA: II-31; Guide : 2.3

Negative List:

z

The right to exclude specific

background

Positive List*:

The right to define the

background needed for the

project

z

z

z

No access to other

Background

Access to all background as

long as needed

* Stated in the RfP, therefore no longer

in conflict with competition law

88

88

Definition: Use

GA: II-1.8, II-29, II-32, II-34

Direct or indirect utilisation of Foreground:

z In further research activities

z

For developing, creating and marketing a

product or process or service

Therefore read all Use clauses twice; once for the purpose of further

research and once for exploitation!

89

89

Access rights GA

II-33, II-34

Foreground

For the

project

Background

If needed to carry out the project

Royalty Free unless

otherwise agreed

Royalty Free

If a participant needs them for using

its own Foreground

For Use

On fair and reasonable conditions or

royalty free – to be agreed

90

90

30

Access rights for Use: DESCA

Art. 9.4

Foreground

Background

If a participant needs them for using its own

Foreground

reasonable conditions

a: Fair/reasonable

for further research

but royalty free for

internal research

b: Royalty free

91

91

Access rights for Use: IPCA

Art. 4.4

Foreground

Background

To all Foreground

is deemed granted

If needed to use

Foreground

Royalty Free

Fair and reasonable

conditions

92

92

IP models

Principle

Value

model

Securing own

investment

Mutual benefit

Open

Innovation

Use

Access only

when “Needed”

and limited

access for

affiliates

All participants

have Access for

Use as well as

their affiliates.

(Joint) Ownership

When used

then

remuneration

to co-owner

No

remuneration

DESCA

IPCA

93

93

31

Dissemination: Publications

Subjects to be covered:

● Right to publish and present your results

● Right to authorship

● Procedure for using data from others

● Procedure for review: right to rais objections, mMaximum period

of delay

● Thesis, degree

94

94

FP7 proposal structure

EPSS – electronic proposal submission system

95

95

Last topic

In the EPSS do not forget the key buttons:

2 page A4

Save form

Upload

Submit

96

96

32

Data Suppliers

Multinational Partners

Data Users

Multinational Clients

TeamRoom

Partner 2

Partner 3

Online

Data Entry System

Data

bases

Reg.

TT

Reg.

Internet Server

Q

Partner 1

Reg.

Online HelpDesk

Partner n

Q

Q == Quality

Quality Control

Control

Reg.

TT

97

97

98

98

99

99

33

100

100

http://www.oceanlab.abdn.ac.uk/esonet/esonim.php

101

101

SPECIFIC

TARGETED RESEARCH PROJECT

Retrieval Of Figurative Images

www.cs.uu.nl/profi

Perceptually-relevant

102

102

34

CHAPTER 2

Building and Managing

a Successful Consortium

1

Building and managing

a successful consortium

Presenter:

● Mette Skraastad, Yellow Research

● Lotte Jaspers, Yellow Research

● Developed in close collaboration with Richard Tomlin (Bluebell

Research)

22

Programme

z

Evaluation criteria

Events and Risks

Governance structures

Balancing interests

z

Lunch

z

Tool

Problem solving

Finances and audit

Closure

z

z

z

z

z

z

33

1

Evaluation criteria

Part I

4

Relevance

to the

Programme

Potential

Impact

&

S&T

Excellence

&

3

3

Consortium

Quality

&

4

Management

Quality

&

3

Mobilisation

of

Resources

&

3

3

FP6 = Maximum 30 and a Threshold of 19

Science & Technology

Relevance

3-4

Impact

Relevance

&

3-4

Implementation

Quality & efficiency

&

3-4

FP7 = Maximum 15 and a Threshold of 10 to 12

55

Impact of the evaluation criteria

Impact

Relevance

Science & Technology

Relevance

3-4

&

3-4

Implementation

Quality & efficiency

&

3-4

Total award: maximum 15 and a threshold of 10-12

66

2

FP7

Core Proposal Structure

z

B1 – Scientific and/or technical quality (concept and

objectives, progress, workplan including work packages,

deliverables and milestones)

z

B2 – Implementation (management structure, individuals,

consortium, resources)

z

B3 – Impact (expected impact, D&E plan, management IPR)

z

B4 – Gender

z

B5 – Ethical or other issues

77

Implementation

Events and risks

Part III

8

What did FP6 consortia look like?

Instrument

No. Contracts

# Participants

# CEC

Contribution

NoE

137

29

7,3

IP

399

25

10

Streps

1165

9

1,9

99

3

Implementation issues

z

Challenges of complexity and scale

z

Communication modalities

z

Communication Barriers

=> Solutions

10

10

Challenges of Scale:

Large Scale Projects

Small to medium scale projects

Deciding on:

• Budget

• Number of participants

• Duration

• Other

11

11

Management work packages

z

Type and number of work packages

z

Interactions and dependencies in relation to

deadlines of Deliverables and accompanying

Milestones

12

12

4

Potential risks

•

•

•

•

•

Management

Financial change

Technical change

Change of partners

Change in dissemination and exploitation

Possible outcome:

Amendment of EC-GA / CA

13

13

Risks

COMMUNICATION

# partners

Technical risks

Alignment

RISKS

Financial risks

Management risks

years

14

14

Communication modalities

Proposal – Consortium Agreement

z

z

z

z

z

Day to day communication

Use of email

Telephone conferencing

Web based application tools (google! Project

management)

Video-conferecing

=> Decision making

15

15

5

Communication Barriers

z

Language

z

Costs of translation

z

IT – firewalls

z

Culture

16

16

17

17

Formal or Informal Collaboration

Formal

Informal

z

Project with goals

Contract

z More than 2 partners

z Structural collaboration

running > several months

z Technical and financial risks

z

z

z

Not well defined project

No contract

z 2 partners

z Ad hoc collaboration

z No technical or financial risk

18

18

6

Governance structure

Efficiency and involvement

19

TREATY

TREATY

FRAMEWORK

FRAMEWORK

PROGRAMME

PROGRAMME

RULES for PARTICIPATION

RULES for PARTICIPATION

Negotiation

Negotiation

Guidance

Guidance

Notes

Notes

SPECIFIC

SPECIFIC

PROGRAMMES

PROGRAMMES

Evaluation

Evaluation

Guidelines

Guidelines

WORK

WORK

PROGRAMMES

PROGRAMMES

Guide to IP

Guide to IP

Rules

Rules

EC – Grant

EC – Grant

Agreement

Agreement

Guides for

Guides for

applicants

applicants

Call

Call

Consortium

Consortium

Agreement

Agreement

Guide to fin.

Guide to fin.

issues

issues

Checklist

Checklist

for a CA

for a CA

20

20

Two contracts

Two structures

B

B

B

P

B

B

C

P

P

P

P

B

B

P

P

B

P

21

21

7

Contractual Structure

EC-Grant Agreement

● ‘Hub and spoke’

● Collective responsibility for management of the

project and delivery of the results

● Individual responsibility for financial management

● EC-GA says NOTHING about how the project is to be

implemented

22

22

Contractual Structure

Consortium Agreement

● ‘Network’ – connects each partner to every other

partner

● Deals with consequences of collective obligations to

the Commission

● Defines obligations of partners to one another

● Says how the project is managed and implemented

23

23

Roles to be divided

z

Contractually: Coordinator, Contractors and

Subcontractors

z

Project support roles: project manager, exploitation

manager and other support

z

Local contractor support roles: financial administrators

and legal etc.

24

24

8

Different Consortium Models for FP7

Coordinator

Core group

All Parties

Postman,

Banker and

Monitor of

implementation

Board

General

Assembly

DESCA

Last in

hierarchal order

of governing

bodies; largely

administrative

role.

Intermediary

between sub

project committees

and GA. Monitors

progress

The decision

making body.

IPCA

Direct relation to

the ‘owners’ of

the project.

Informs the

Board and EC

about the

implementation

‘Owners’ of the

project:

-Strategic decisionmaking.

- Market

orientation.

Marginal role it

is the safety

valve in case of

serious dissent

within the

Board.

25

25

26

26

Controlling Tasks

z

z

z

z

z

z

z

z

Science

Internal information and communication

Administration

Finance

Legal aspects

Ethics

Exploitation

Dissemination

Who and at which level ?

27

27

9

Control versus mandate

z

Unclear project and tasks

z

Heavy management

Well defined project, goals and

tasks

z Lean management

z

Permission for every step

z

Delegated mandate and report

z

???

z

Trust

z

Time consuming

z

Efficient

z

28

28

Balancing interests

PART IV

29

Personal Benefit – Mutual Benefit

WHAT

WHO

●

●

●

●

Yourself

Project members

Affiliates

Others

● Project

● Future research

● Exploitation

● Publications

30

30

10

Important to researchers

z

The right to publish results in peer reviewed journals.

z

The right to present results on a congress or in a

meeting.

z

The right to use the results for further research,

preferable world wide.

31

31

Important for research groups

z

The right to collaborate with third parties, including

further research.

z

The right to receive reimbursement via license

agreements for developing and/or selling the invention.

z

Precise labelling of pre-existing know how and

knowledge

32

32

Important to Industry

Interest is sector specific:

z

Exclusive patent rights when one patent means one

product; reimbursement is open for negotiation

z

Access to all knowledge including patents when aim is

developement of a new standard; no reimbursements

33

33

11

Results could be anything

Data or Human Material

Publications, Repositories

Software: Technical, Business,

Application

License, Open Source Public domain

Policy Recommendations:

Workshops, websites

Some forms of

Project Results

Inventions (New matter

or new process) : License / sale

Database and Repositories:

Research Tool

34

34

Collaboration aims

Standardisation

New product

ICT – Transport

z Technology platform –

multiple producers

z Further research

Health - Biotech

z Single product – one

producer

z Further research

35

35

Access rights for partners

z

What are the results

z

Who owns the results

z

What are the access rights for

partners for:

z

Who pays for the patent costs

z

Who is responsible for

exploitation

z

Which parties need to be

involved, directly or indirectly

● further research

● exploitation

● dissemination

z

What are the exploitation and

dissemination strategies

36

36

12

Access Rights

z

Choose a model: Value model, Open Innovation or

another model

z

Define the terms for access to Background

z

Define the terms for Use of Foreground

z

Use for further research

z

How is access provided? Written request ‘deemed’?

37

37

IP Models in IPCA and DESCA

Principle

Value

Model

Use

(Joint)

Ownership

Securing own Access only

when “Needed”

investment

When used

than

remuneratio

n to coowner

DESCA

All participants

have Access for

Use as well as

their affiliates.

No

remuneratio

n

IPCA

and limited

access for

affiliates

Open

Mutual

Innovation benefit

38

38

Assessment Tool

PART V

39

13

Bringing together different interests

z

Identify the Individual Interests of partners: common and

differences

z

Align these interests

●

●

●

●

z

Clear objectives and goals

Committed people

Effective project management

Create win-win situation

Take into account cultural differences

40

40

How good is your Consortium?

Consortium Assessment Tool:

z

12 success factors identified

z

Scores strength and stability of a Consortium

z

Useful when building a consortium

41

41

Key Success factors

Structure

z

History of working together

z

Sufficient flexibility

z

Open and clear communication

z

Project plan reflects vision and goals of the partners

z

Right mix of partners – no conflicts of interest

z

Quality of Management

Management:

Management structure fits the consortium dynamics

z

Efficient administrative systems and support

z

Transparency in project finances and accounting

z

Research and Evaluation

z

Clear set of rules on intellectual property

z

Dispute avoidance and dispute resolution

z

42

42

14

Problem solving

Avoiding and resolving conflicts

43

Avoiding conflicts

z

z

z

z

z

z

z

z

Clear project, goals and tasks

Risk assessment

Minimising interdependencies

Open communication

Possibility to address issues in a meeting

Clear management structure

Clear decision making structure

Clear voting

44

44

Decision making

z

Voting:

● Qualified Majority

● Simple Majority

● Veto

● Limited Veto’s

● Unanimous

● Quorum

45

45

15

Decision making 2

How to make decision

z

z

z

z

In writing and/or hand raising

In a meeting

Electronic

????

46

46

Decision making 3

Level of decision and mandate

z

Who prepares decision

z

All decisions at highest level

z

Decisions on highest level and lower level

● Categorising topics

● Impact of decisions

● Safety valve

47

47

Resolving conflicts

z

Informal discussion within work package

z

Formal discussion at Board level

z

Formal decision

z

Safety valve ?

z

Legal steps

48

48

16

Finances and Audit

Achieving transparency and control

49

Financial Structure

Third party contract:

z Maximum budget

z Fixed price per task

z Budget allocation in

accordance with project

plan

Consortium Agreement:

• Financial management

• Changes of budget

allocation

• Allocation of work to another

partner

• Financial reponsibility

50

50

Coordinator Responsibilities

z

To distribute payments in accordance with Consortium

decisions

z

To inform partners about budget, costs etc

z

Monitor compliance with contracts (EC-GA) and verify

reports

51

51

17

Contractor Responsibilities

z

To maintain proper records

z

To prepare and submit financial statements and – if

necessary - certificates

z

To agree financial arrangements with Consortium re.

pre-financing and cost limits

z

To carry out the work of the project

52

52

Time recording and reimbursement

Time recording of staff

• Method of recording; fair allocation method

• One or more projects

• One or more activities

• Effect of fixed price per deliverable

• Planned time = planned costs => money

• Actual time < planned costs => less money

• Actual time > planned costs => gap money

53

53

Audit

z

z

z

z

Right to conduct audit

Access rights

Type of audit: financial and/or technical

Auditor selection

54

54

18

Conclusion

z

Building and managing a

consortium is a continuous

process

z

Therefore: Talk every step

through and repeat

55

55

How to start ?

z

z

z

z

z

z

z

z

Identify one or more partners

Discuss ideas and write a plan on 2-4 A4’s

Identify and ask other partners

Talk with experienced people and support management.

Use guidelines.

Discuss the draft plan and write a plan on 8-15 pages

using a proposal guideline

Discuss the plan again with partners and advisors

Ask the missing partners

Write a first proposal draft and discuss it

56

56

19

How to bridge gaps?

State agencies

Customs,

Police, etc.

Ministries of

trade,

transport, etc.

Big companies

and associations

in various sectors

Exporters,

importers,

freight forwarders,

software companies

banks, SMEs

etc.

Business

BBR and YR, slide 75

Possible structure

BBR and YR, slide 76

1

Data Users

Multinational Clients

Data Suppliers

Multinational Partners

Partner 1

Partner 2

Partner 3

Online

Data Entry System

Data

bases

Reg.

Internet Server

Q

TeamRoom

Reg.

TT

Reg.

Online HelpDesk

Partner n

Reg.

TT

Q

Q == Quality

Quality Control

Control

BBR and YR, slide 77

BBR and YR, slide 78

2

BBR and YR, slide 79

BBR and YR, slide 80

3

BBR and YR, slide 81

BBR and YR, slide 82

4

BBR and YR, slide 83

BBR and YR, slide 84

5

National / international Partners

- BPS Consortium

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Attorney Heyland (Brüssel and Königswinter/Bonn)

useConsult (Bornheim/ Bonn) QM

Strategem (Manchester)

Arttic France (Paris, Marseille)

Nexture Consulting srl (Ivrea)

Comase (Charleroi)

German-Greek Chamber of Commerce and

Industry (Athens)

• German-Swedish Chamber of Commerce and

Industry (Stockholm)

• Inmark (Madrid) BBR and YR, slide 85

BBR and YR, slide 86

6

BBR and YR, slide 87

BBR and YR, slide 88

7

BBR and YR, slide 89

BBR and YR, slide 90

8

BBR and YR, slide 91

BBR and YR, slide 92

9

CHAPTER 3

GUIDE:

Handling the Evaluation Criteria:

Impact and Implementation

Version

7.0

8.0

9.0

Changes made

Conceptual Framework: new chapter introduced on interrelation of impact on B1 and

B3 proposal incorporated,

Chapter “Results and Deliverables” rewritten

Impact: new chapters introduced on dissemination, confidentiality, commitment letter

and database.

Rewritten the discussion on internal research in further research.

Governance: completely rewritten chapter with regard to other parties influencing

research, dissemination and exploitation

Governance: 3.2 management structure DESCA, 3.3 terminology changes

Publication: annotation regarding publication in DESCA and IPCA

Edited: Sarah Jones editing

Authors:

Lotte Jaspers,

Mette Skraastad,

Jet van Dijk

Contributors:

Richard Tomlin, Bluebell Research

Margot Spaargaren, TTLegal

Page 1 of 108

Table of Content

Conceptual Framework

1.0

1.1

1.2

1.3

1.4

1.5

1.6

1.7

1.8

1.9

The Legal Documents of FP7................................................................................... 4

FP7 Consortium Agreement Models ...................................................................... 11

Open Innovation ..................................................................................................... 13

The Value Model .................................................................................................... 15

Individual Benefit and Mutual Interest .................................................................... 17

FP7 - The Competitive and Dynamic Knowledge Economy................................... 18

Impact of the FP7 evaluation criteria ...................................................................... 19

Impact – Policies and Strategies IPR ..................................................................... 21

Generating Impact through Dissemination and Exploitation................................... 26

Results and Project Deliverables............................................................................ 28

Impact

2.1

2.2

2.3

2.4

2.5

2.6

2.7

2.8

2.9

2.10

2.11

2.12

Exploitation and Research Activity Strategies ........................................................ 31

Dissemination ......................................................................................................... 34

Negotiation conclusions ........................................................................................ 36

The project spin-out company ................................................................................ 38

Software ................................................................................................................. 41

Access rights to software ....................................................................................... 44

Open source........................................................................................................... 47

Databases .............................................................................................................. 48

Confidentiality ......................................................................................................... 51

Letter of Commitment ............................................................................................. 54

Dissemination - Publications .................................................................................. 56

Further Research ................................................................................................... 60

Governance

3.0

Governance - Introduction ...................................................................................... 63

3.1

Management Structures, drawing the Consortium organogram ............................ 66

3.2

Governing bodies ................................................................................................... 68

3.3

Societal & Stakeholder Involvement ...................................................................... 70

3.4

Decision-making and voting .................................................................................. 75

4.0

Barometer for EU Consortia ................................................................................ 78

4.1

Introduction............................................................................................................. 78

4.2

Consortium Score Card .......................................................................................... 79

Schedule 1: Scoring a Starting Consortium ........................................................................... 80

Schedule 2: Scoring a Running Consortium .......................................................................... 81

Schedule 3: Reading the Scores............................................................................................ 83

Financial Basics

5.1

5.2

5.3

Framework Eligible Costs....................................................................................... 85

The Financial Structure .......................................................................................... 87

Financial Provisions Desca .................................................................................... 92

Annexes

Annex 1:

Annex 2:

Annex 3:

Annex 4:

Annex 5:

Annex 6:

Dissemination and Exploitation Strategies – checklist ....................................... 84

Ethical Issues in EU Research Proposals – checklist ........................................ 86

Glossary – Dissemination and Exploitation ........................................................ 90

Glossary – Project Management ........................................................................ 92

Glossary – Ethical Issues ................................................................................... 95

Glossary – Gender ............................................................................................. 96

Page 2 of 108

Part I :

Conceptual Framework

Page 3 of 108

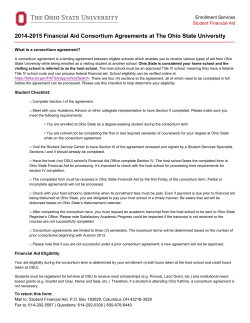

1.0 The Documents of FP71

The picture below shows the relationships of the different legal and other documents

pertaining to the Seventh Framework Programme.

TREATY

FRAMEWORK

PROGRAMME

RULES for PARTICIPATION

Negotiation

Guidance

Notes

SPECIFIC

PROGRAMMES

Rules for

evaluation

WORK

PROGRAMMES

Guides for

applicants

Call

Guide to IP

rules

EC – Grant

Agreement

Consortium

Agreement

Guide to

fin. issues

Checklist

for a CA

Treaty

Treaty establishing the European Community (Nice Consolidated Version) - Part

Three: Community Policies - Title XVIII: Research and Technological Development Article 163 - Article 130f - EC Treaty (Maastricht Consolidated Version)

Articles 163 to173 lay down the framework for the EU policies with regard to:

- a multi annual framework programme for RTD

- setting up structures for the execution of such programmes (Article 169)

- setting up community joint undertakings (Article 171).

The structure and relationship of the legal documents as discussed below regard

obligation of the Commission to set up a multi annual framework for RTD. The

structure of the Euratom framework is almost similar as FP7 but is not discussed

here.

Framework Programme

1

Version 4_0

Page 4 of 108

Decision No 1982/2006/EC of the European Parliament and the Council of 18

December 2006 concerning the Seventh Framework Programme

Annex I

Criteria for selecting the themes and objectives of community activities

Annex II

General outlines of community activities, scientific and technological

objectives and related priorities

Annex III

Seventh Framework Programme (2007 to 2013) amounts and

breakdown

Annex IV

Rules for financial participation by the community

Explanation: This decision is the foundation upon which the Commission is allowed

to support RTD activities. It concerns the thematic programmes, budget and the

basic requirements for FP7 projects. The annexes work out the criteria in more detail.

Specific Programmes

Council Decision on adopting a specific programme for research, technological

development and demonstration on (specific programme name)

Annex I

Indicative breakdown of the amount deemed necessary

Annex II

The general outlines, the scientific and technological objectives and

the priorities

Annex III

Specific rules for implementing the specific programme

Annex IV

Selection criteria for the implementation of the specific programme

The specific programme contains the key themes and priorities as agreed by the

Council and the European Parliament. Each specific programme has a specification

of the budget allocated for each theme and the funding schemes. The specific

programme provides the background information with regard to the aim and

objectives of each theme.

Work Programmes

The work programme is drafted by the Commission and specifies the implementation

of the specific programmes. The Commission consults the Programme Management

Committees, European Research Community via expert groups, and members of the

Technology Platforms and other stakeholders. The work programme comprises

detailed descriptions of the activities ~ detailed thematic priorities and research

topics, funding schemes used, indicative budget (plus budget breakdown), deadlines,

and the evaluation procedure. It provides all information necessary to launch calls for

proposals. The extent to which a proposal addresses the objectives of the work

programme is an evaluation criterion, ie: in order to prepare a successful proposal,

one has to carefully read the work programme related to the call addressed.

Calls

The official invitation to submit proposals for funding to the European Commission is

issued by calls for proposals. To the call belongs a so-called call fiche which will

detail the topics covered, indicative budget and deadlines. This document is virtually

identical to the annex of a work programme.

Guide for Applicants

Page 5 of 108

For each call the EC provides a guide describing how to apply for funding. This guide

contains general information about the funding scheme, how to apply, checklist and

procedure. The general information may vary slightly per call or work programme.

This guide contains also call-specific information such as timetable, evaluation

criteria, procedure and instructions to fill in Part A (administrative section) and Part B

(the proposal itself). This is the most important document for scientists writing a

project proposal. This guide is updated for every new call.

Rules for Submission, Evaluation, Selection and Award

This document describes the rules for proposal submission and the procedure for

evaluating, selecting and awarding proposals. The EC publishes electronically a call

for proposals for each work programme and funding scheme. After the closing date,

the EC checks whether the proposal is eligible according to the Rules for

Participation and the scope of the call.

Individual Assessment:

For each project proposal, 3 evaluators are assigned, 5 for Network of Excellence.

These evaluators have been carefully selected, based on their knowledge and

expertise in, eg: the scientific field, management or exploitation of results. Each

evaluator marks the proposals according to the evaluation criteria and gives written

comments. The outcome is an Individual Assessment.

Consensus Assessment:

In the next phase these individual assessments are discussed in a consensus

meeting to reach a consensus on the scores and comments. The evaluators also

consider whether the proposal falls within the scope of the call and deals with ethical

or security issues. This process is monitored by the EC (Monitor). The outcome is a

Consensus Report written by a Rapporteur, one of the evaluators.

Final Assessment:

In the next phase a Review Panel examines and compares the Consensus Reports

and gives, if necessary, new scores. If applicable, the Review Panel organises

hearings with the Applicants who have passed the thresholds. If applicable, the

Review Panel resolves minority reviews, prioritises proposals with the same scores

and recommends clustering or combining proposals. The outcome is an Evaluation

Summary Report which contains lists of selected, prioritised, rejected and ineligible

proposals.

The EC notifies the Coordinator of selected proposals and, depending upon the

negotiation, the proposal may be awarded.

Page 6 of 108

Rules for Participation

Regulation No EC/1906/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18

December 2006 laying down the Rules for Participation of research centres and

universities in actions under the Seventh Framework Programme and for the

dissemination of research results (2007-2013).

This document contains the basic requirements for participation in FP7 projects. The

legal framework of the RfP is subject to:

1.

State Aid Framework for Research, Development and Innovation;

2.

Financial Regulation

3.

Political needs

The RfP regulates:

Partner Eligibility

Proposal, Submission, Evaluation and Negotiation

Legal and Financial Rules

Community Financial Contribution

Maximum Funding Rates

Implementation and Grant Agreement

Cost Reporting

Intellectual Property Rights

Procedures for Appointment of Experts

Grant Agreement (GA)

The grant Agreement may specify some, or most, of the requirements as laid down in

the RfP. It consists of several parts:

The core Grant Agreement.

- Annex I

Description of Work;

- Annex II

General conditions;

- Annex III

Specific provisions related to the specific instrument

- Form A

Accession of Beneficiaries to the Grant Agreement (Annex IV)

- Form B

Request for Accession of a New Beneficiary (Annex V)

- Form C

Financial Statement per Funding Scheme (Annex VI)

- Form D

Terms of Reference for the Certification of Financial Statements (Annex

VII)

- Form E

Terms of Reference for the Certification of the Methodology

Page 7 of 108

EC-Grant Agreement

Fig. 1: the Hub and spoke relation of the

Generally speaking, the Grant

Commission with the Beneficiaries

Agreement for collaborative research

projects regulates the relationship that

the Commission has, or wants to have,

with the members of the Consortium. The

Commission is not concerned with

Beneficiary

matters related to how the project is

Beneficiary

Beneficiary

implemented by the Consortium, how

deadlines are kept, access rights are

provided etc. The Grant Agreement is a

contract designed to protect the interests

of the European Community. These

Cie

interests are of a political (Lisbon agenda BeneBeneficiary

ficiary

etc), legal and very much of a financial

nature, eg: with regard to recovery of

amount to be retrieved by the

Commission from one or more

beneficiaries. Consider that the

Beneficiary

Beneficiary

Commission contract is designed as a

hub with spokes. The Commission is the

Beneficiary

hub; the Commission has a contractual

relation with all Beneficiaries. The

Beneficiaries (the spokes) are only linked

to the other Beneficiaries via the hub. A

direct relationship of the Beneficiaries is

shown right.

Consortium Agreement

With regard to collaborative projects the

call can make the conclusion of a

Consortium Agreement mandatory. The

beneficiaries are free in the design of

their Consortium Agreement. The main

purpose of a Consortium Agreement is

to specify the relationship of the

members of the Consortium towards

each other regarding the

implementation of the project. The MGA

makes, in Article II.4, some suggestions

of issues to address in the Consortium

Agreement:

- Internal organisation and dispute

resolution

- Distribution of CEC contribution;

- Settlement of disputes

- Access rights

- Liability, indemnification and

confidentiality

Fig. 2: Nodal linkage of Consortium parties

to each other

Party

Party

Party

Party

Page 8 of 108

Party

Part

y

Party

Party

FP7 Negotiation Guidance Notes

When you are invited to Brussels to negotiate your project, this guide outlines the

information and procedures of the negotiation process.

Guide to Financial Issues

The guide to financial issues is a comprehensive guide explaining all the financial

issues related to the European Commission Grant Agreement. This Guide treats

each topic in the order as presented in the Grant Agreement.

Guide to Intellectual Property Rules

This document provides an overview to the Intellectual Property Rights as presented

in the legal documents of FP7: Rules for Participation and the Grant Agreement. It is

a guide to the various issues and potential pitfalls regarding IPR that participants may

encounter when preparing and participating in an FP7 project.

Checklist Consortium Agreements

This document provides non-binding guidance to FP7 participants regarding the

issues they may wish to address in their Consortium Agreement.

Flowchart of the conclusion of contracts

The call may stipulate that a Consortium Agreement is mandatory. For most Large

Scale Integrated Projects (Funding Scheme for large collaborative projects) a

Consortium Agreement will be required. The Grant Agreement specifies in Article 1.4

that a Consortium Agreement is deemed to be concluded. Therefore the Commission

assumes that such a Consortium Agreement is in place before the Commission itself

signs the Grant Agreement. This assumption affects the timing of the conclusion of

the Consortium Agreement, the Grant Agreement and the Accession Forms.

The sequence for signing the documents:

The Accession Forms can only be signed after the Grant Agreement has been

signed because one can only accede to an Agreement when there is an Agreement

in place! Therefore the Grant Agreement is signed by Coordinator and Commission.

The Grant Agreement gives the Coordinator 45 days to have the Accession Forms

signed by the other members of the Consortium.

Between signing the Grant Agreement and the Accession Form, the Consortium

Agreement could/should be signed. Some model Consortium Agreements are drafted

to be signed already in the project preparation phase and require parties, when the

project is selected for funding, to sign the Accession Form as swiftly as possible.

When taking the point of view that the Consortium Agreement should at least be in

place before the Accession Forms have to be signed, the following flowchart unfolds:

Page 9 of 108

1 Conclusion

Consortium

Agreement

time

2 Conclusion

EC-GA

Within 45 days

3 Signature and

submission to

Commission of

Accession Forms

European Commission

1. – EC-GA: Coordinator

concludes MGA with EC on

behalf of the Consortium

3. - Accession

Forms binding the

Beneficiaries to

MGA

Coordinator =

Beneficiary 1

2. – CA:

Between

Beneficiaries

Beneficiary 2

Beneficiary 3

Beneficiary 4

Subcontract

Subcontractor

Page 10 of 108

Beneficiary n

1.1 FP7 Model Consortium Agreements2

At the start of FP7, several models for Consortium Agreements have been

presented. The models are all based on FP6 predecessors3. Different sectoral

interest groups of industry, academia and research organisations have developed the

following models:

- IPCA by ICT and telecom industries;

- DESCA by academia and research organizations;

- EU-Car by the automotive industries

- IMG by the aerospace industries

IPCA

The IPCA model is developed by the European Information & Communications

Technology Industry Association (EICTA). This group of ICT and telecom industries

have a longstanding tradition of developing sector-specific Consortium Agreement

models. They have done so since the beginning of the Framework Programmes. The

procedure for the development of such Consortium Agreements is well-organised

and strict. It is necessary to have such strict procedures because all members of

EICTA must feel comfortable using the end result of their negotiations for their own

participation in FP7 consortia. For FP7, just as in the previous Framework

Programmes, EICTA has made use of the IPCA model developed for FP6, making

sure that the FP6 model fitted the objectives and legalities of FP7. Some serious

redesigning has been undertaken:

- Rights for affiliates;

- Joint ownership rights;