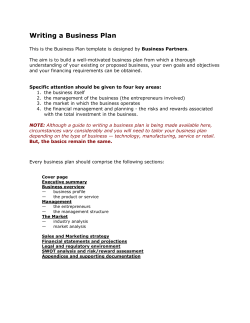

How to valuate a Social Enterprise? NTI University/ Business School Nederland