Expert Testimony: How to Prepare Your Expert

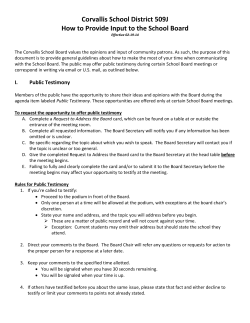

Expert Testimony: How to Prepare Your Expert and/or How to Be an Expert Howard Seife, Moderator Chadbourne & Parke LLP; New York William Q. Derrough Moelis & Company; New York Hon. Barbara J. Houser U.S. Bankruptcy Court (N.D. Tex.); Dallas Barry W. Ridings Lazard; New York Bonnie Steingart Fried, Frank, Harris, Shriver & Jacobson LLP; New York 207 NEW Online Tool Researches ALL ABI Resources Online Research for $275 per Year, NOT per Minute! With ABI’s New Search: • One search gives you access to content across ALL ABI online resources -- Journal, educational materials, circuit court opinions, Law Review and more • Search more than 2 million keywords across more than 100,000 documents • free for all ABI members *Cost of ABI membership One Search and You’re Done! search.abi.org 44 Canal Center Plaza • Suite 400 • Alexandria, VA 22314-1546 • phone: 703.739.0800 • abi.org Join our networks to expand yours: © 2012 American Bankruptcy Institute All Rights Reserved. American Bankruptcy Institute MakeSureIncredibleExpertIsAlsoCredible Contributing Editor: Brian L. Shaw Shaw Gussis Fishman Glantz Wolfson & Towbin LLC; Chicago bshaw@shawgussis.com Also Written by: Mark L. Radtke Shaw Gussis Fishman Glantz Wolfson & Towbin LLC; Chicago mradtke@shawgussis.com B ankruptcy litigators often find themselves embroiled in litigation in which expert testimony is critical to the case, if not outcome-determinative. The most obvious example—valuation—routinely plays an important role and requires expert testimony to assist the judge. For example, value is prevalent in contested matters or adversary proceedings involving relief from the automatic stay (§ 362), use of cash collateral (§ 363), secured claims (§ 506), avoidance actions (§§ 544, 547 and 548) and plan confirmation (§ 1129), among other matters. Of course, there are many other issues in bankruptcy cases that similarly require specialized expertise. Litigators sometimes have the luxury of handpicking their testifying experts. Other times an expert has already been chosen because of pre-existing relationships. Regardless Brian L. Shaw of the situation, a litigator rarely goes into a case with a mindset that his or her expert is lousy. (And on the rare occasion that one does think so, the case tends to settle quickly.) Instead, a litigator believes (rightly or wrongly) that the expert will help to deliver a victory. As a case progresses, the expert’s Kool-Aid starts to taste even better, and it is easy to become increasingly enamored with an expert and your case. In order to ensure that your incredible expert is also credible, numerous practical issues should not be overlooked—both when selecting and retaining your expert and before any report is distributed. Rule 702 and Daubert Issues1 The admissibility of expert testimony is governed by Rule 702 of the Federal 1 Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals Inc., 509 U.S. 579 (1993) (seminalcaseonadmissibilityofscientificexperttestimony). 50 September 2011 About the Authors Brian Shaw and Mark Radtke are members of Shaw Gussis Fishman Glantz Wolfson & Towbin in Chicago. Mr. Shaw also serves as ABI’s Vice President-Membership. Rules of Evidence (FRE), made applicable in bankruptcy proceedings by Rule 9017 of the Federal Rules of Bankruptcy Procedure. FRE 702 provides for the admission of expert testimony to assist the trier of fact where “(1) the testimony is based upon sufficient facts or data, (2) the testimony is the product of reliable principles and methods and (3) the witness has applied the principles and methods reliably to the facts of the case.”2 Unless expert testimony is both reliable and relevant, it is inadmissible.3 The trial court has a “gatekeeper obligation” to ensure that expert testimony is both relevant and reliable.4 Although as a practical matter bankruptcy judges may often ignore the gatekeeper obliga- cialized education and experience. When an expert intends to rely on experience, “the witness must explain how that experience leads to the conclusion reached, why that experience is a sufficient basis for the opinion, and how that experience is reliably applied to the facts.”7 “The expert’s testimony should also be grounded in an accepted body of learning or experience in the expert’s field.”8 In addition to determining reliability, the court must determine whether the proffered testimony is relevant. “Testimony is relevant if it assists the trier of fact in understanding the Mark L. Radtke evidence or in determining a fact at issue.” 9 Even reliable testimony may be barred if it does not meet the standard for relevance. Just as important, even otherwise reliable and relevant testimony may be discredited if Building Blocks I tion prior to trial and admit expert testimony where no jury is involved, good litigators perform their own gatekeeper analysis to ensure that their expert’s testimony will be reliable and relevant and to assess the relative strength or weakness of their case. To determine whether an expert’s testimony is reliable, the court must make a preliminary assessment of whether the reasoning or methodology underlying the testimony is valid.5 In order to pass the reliability hurdle of the Daubert test, an opinion must consist of more than simply “subjective belief or unsupported speculation.”6 More often than not, in bankruptcy litigation an expert is not relying on some scientific knowledge, but is testifying on a subject matter (such as value) that requires spe2Fed.R.Evid.702. 3 Kumho Tire Co., Ltd v. Carmichael,526U.S.137,147(1999)(expanded Dauberttononscientificexperttestimony). 4 Daubert, 509 U.S. at 589. See also Ueland v. United States, 291 F.3d 993, 997 (7th Cir. 2002) (expert testimony may be received only if expertis“qualifiedasanexpertbyknowledge,skill,experience,trainingoreducation...[and](1)thetestimonyisbaseduponsufficientfacts ordata,(2)thetestimonyistheproductofreliableprinciplesandmethodsand(3)thewitnesshasappliedtheprinciplesandmethodsreliably tothefactsofthecase”). 5 Daubert,509U.S.at592-93. 6 Cummins v. Lyle Industries,93F.3d362,368(7thCir.1996). an expert is not credible. It is accordingly important to address practical issues that will protect and even enhance the credibility of a testifying expert. Practical Issues: Selecting and Retaining an Expert Before assessing prospective experts, a litigator must first do some homework. You must know if your bankruptcy judge has written any opinions involving the subject matter of your expert’s testimony, what the judge is looking for from an expert and how other experts may have hurt their credibility before your judge. If no such opinions exist, you should identify any other opinions regarding the subject matter of your expert’s testimony. The information you acquire should guide your selection of the right expert for your case. How do you then determine who your expert should be? There is not a one-size-fits-all answer. Sometimes, 7 In re Husting Land & Dev. Inc.,255B.R.772,781(Bankr.D.Utah2000) (quotingAdvisoryCommitteeNotes,AmendmentstoFed.R.Evid.702 (effectiveDec.1,2000)). 8 Id. 9 Masters v. Hesston Corp.,291F.3d985,991(7thCir.2002). ABI Journal 209 Mid•Level Professional development Program you will not practically be able to look beyond a particular expert or firm. If you have the autonomy to select any expert you want, you have to ask yourself several questions. Are you going to be satisfied with a generalist who has some experience with a particular industry, or are you going to find the industryspecific expert? Is industry even important in your case? You obviously do not want a manufacturing expert for a real estate case or a real estate expert for a retail case. What exactly will the scope of the project be? For example, do you need your valuation expert to prepare a liquidation analysis and a going-concern analysis? Does your expert have a predisposed bias for utilizing a certain method? These questions address issues that may affect your expert’s credibility and must be evaluated in context. Experts’ Reputations Often Precede Them Especially in the bankruptcy and restructuring world, an expert can be preceded by his or her reputation (good or bad). The often-used saying, “It’s a small world,” applies with even greater force in bankruptcy circles. It usually does not take long to find someone who has had some experience with a particular expert. Thus, reputations are often formed by the perceptions of peers. Those perceptions range from staffing of assignments (do you want an expert who digs into the minutia, or who sweeps in at the end to compile the analyses?) to experience and beyond. However, those perceptions do not always mirror reality. It is a good idea to perform your own examination of an expert’s credentials even if he or she comes highly recommended. Every expert comes with a preexisting package of attributes that affect that expert’s credibility for any given case. One set of attributes is generally found in the expert’s curriculum vitae and includes such information as the expert’s employer, education, training, professional experience, publications and prior cases. This information will give you a general understanding of whether the proposed expert generally fits the needs of your case, but it does not tell the whole story. You must dig deeper. While weeding out a bad expert is typically not difficult, selecting among high-quality experts can be. Even if your expert is a well-known superstar, he or she may not be the best fit for your case. Existing law does not always align with your expert’s view of ABI Journal 210 the subject. For example, valuation literature permits an analyst to choose from various approaches to value a business as a going-concern, but some cases favor certain approaches. Just as you do not want an expert who performs a superficial analysis of available data, you do not want an expert who undertakes a mission to use your case as an opportunity to change law. In a case where you know a certain approach is required, you want to select the expert who already subscribes to that approach. An expert’s approach may already be known to you because he or she has testified credibly in several written opinions, but it is sometimes difficult to track an expert’s prior positions on a particular subject matter. You must start by performing an exhaustive search of written opinions involving testimony by your prospective expert. Just because a particular expert has an adverse opinion on his or her record does not mean that you should eliminate that expert from contention. You must consider how that black mark may affect credibility in your case and how badly you need the expert’s specialized knowledge. If your expert is a generalist, it is easier to simply move on to the next candidate. If your expert has unique industry experience, you may have to retain that expert. In addition to exploring your expert’s prior opinions and approach, including his or her success or failure before another court, you must determine the extent to which your potential expert may have had prior experience with the judge. The easiest way to understand whether your expert already has some credibility before a particular judge is to ask the expert. Be careful to not fall into the trap of overvaluing an expert’s pre-existing credibility before the court. Reputations may set experts apart but are not guarantees of success. Compensation May Unintentionally Affect Credibility Compensation issues may also affect your expert’s credibility. If you are not yet in the midst of litigation but anticipate that an expert’s opinion may someday be needed to prove a disputed issue, contingent-fee or incentive-based compensation should be avoided. The TOUSA bankruptcy case provided a prime example of how a contingentfee compensation arrangement can cast doubt on an expert’s credibility and invalidate opinions. 10 In connection 10 In re TOUSA Inc.,422B.R.783,839-40(Bankr.S.D.Fla.2009),rev’d on other grounds,444B.R613(S.D.Fla.2011). with a pre-petition financing transaction, TOUSA agreed to pay its expert $2 million if the expert ultimately opined that TOUSA was solvent, but only the expert’s hourly fees and reimbursement of expenses if the expert could not render an opinion that TOUSA was solvent. 11 Given that, among other things, the expert’s hourly fees and actual expenses amounted to less than half of the $2 million contingent fee the expert was ultimately paid for a solvency opinion, the bankruptcy court concluded that the expert’s opinion was “unpersuasive.”12 In short, contingent fees and incentive-based compensation are big red flags that should be avoided. These types of compensation arrangements may have validity under certain circumstances and for certain fields of expertise based on industry customs, but it is generally advisable to avoid them in bankruptcy litigation. Contingent-fee and incentive-based arrangements are not the only type of expert-retention pitfalls that should concern a litigator. The magnitude of an expert’s fees and the circumstances of an expert’s retention may also inadvertently provide fodder for your opponent to attack your expert’s credibility. Practical Issues Testing Opinions Recent amendments to the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure have thankfully eliminated the silly gymnastics that lawyers and experts would have to engage in to avoid the creation of discoverable work product. Under the old rules, courts would generally allow discovery of all drafts of an expert’s report, along with all communications between the expert and lawyer. Those drafts and communications are now generally protected.13 Litigators should take advantage of the improved rules to ensure that they take every possible step to protect and enhance their experts’ credibility, especially before submission of the expert report. Before distribution of an expert’s final report, there are a number of things that a litigator should do to test the opinions and enhance credibility. Nothing is worse than a litigator who assumes that his or her expert knows everything and is afraid to ask questions or challenge the expert (unless you are that litigator’s 11 Id.at839. 12 Id. 13Fed.R.Civ.P.26(b)(4). continued on page 79 September 2011 51 American Bankruptcy Institute Building Blocks I: Make Sure Your Incredible Expert Is Also Credible from page 51 opposing counsel). It is assumed that a qualified expert has specialized knowledge that may assist the court. The question is how well the expert knows his or her craft, especially as compared to a competing expert. The key is to explain, explain, explain! An expert’s credibility will often be enhanced if he or she can clearly explain reasoning in layman’s terms in his or her report (and testimony) without forcing the judge to independently attempt to learn the complex underpinnings. A litigator must instruct his or her expert to avoid analytical leaps. If you do not understand what the expert is attempting to explain when you read the report or discuss the topic, chances are the concept will also be lost on the judge. Frustration over the inability to understand what an expert is attempting to convey will likely erode credibility and open the door for your opponent to further attack your expert’s credibility. It is important to explore with your expert different ways of presenting the same concept. The presentation is typically improved if your expert breaks down dense concepts into separate and simplified explanations. Keep in mind that your expert likely knows the concepts better than you (and hopefully anyone else), but you know the best way to present those issues in the report and when testifying before the court. The existence of dense concepts is not the only reason to challenge your expert to provide better explanations. You must similarly challenge your expert to provide an expanded explanation of his or her thought processes when it is apparent that the expert is assuming too much and risking a loss of credibility due to a superficial analysis of the key inputs.14 Assumptions must be supported by detailed analysis of underlying data rather than superficial analysis. If you ever find yourself wondering “why” (why did the expert assume this, why does the report not provide a level of detail that you would expect given your experience or existing law, etc.), you must ask the question and ensure 14“[A]n expert’s report that does nothing to substantiate this opinion is worthless,andthereforeinadmissible.”Minasian v. Standard Chartered Bank PLC,109F.3d1212,1216(7thCir.1997).“Anexpertwhosuppliesnothingbutabottomlinesuppliesnothingofvaluetothejudicial process.” Mid-State Fertilizer Co. v. Exchange Nat’l Bank, 877 F.2d 1333,1339(7thCir.1989). that your expert’s report provides an understandable answer. Unless the circumstances warrant, you should also ensure that your expert avoids hedging words such as “appears,” “seems” and the like, all of which suggest some level of speculation or uncertainty. Plus, there is always the smell test. Your expert’s assumptions and opinions should pass it. Trust your instincts and willingly challenge your expert. Why risk a potential loss of credibility or invalidation of your expert’s opinions? Conclusion The selection of an expert cannot change the facts or law of a case. However, the right expert can often positively or negatively change the manner in which a judge (or jury) perceives the facts and applies them to the applicable law. How much weight your expert is given by the trier of fact and the court (usually the same in bankruptcy land) will be directly related to his or her credibility and reception by the judge. Accordingly, do not take the selection process and credibility assessment lightly, as it is a vital part of any litigation process. n Copyright 2011 American Bankruptcy Institute. Please contact ABI at (703) 739-0800 for reprint permission. ABI Journal September 2011 79 211 American Bankruptcy Institute Federal Rules of Civil Procedure Rule 26(a)(2) Disclosure of Expert Testimony. (A) In General. In addition to the disclosures required by Rule 26(a)(1), a party must disclose to the other parties the identity of any witness it may use at trial to present evidence under Federal Rule of Evidence 702, 703, or 705. (B) Witnesses Who Must Provide a Written Report. Unless otherwise stipulated or ordered by the court, this disclosure must be accompanied by a written report— prepared and signed by the witness—if the witness is one retained or specially employed to provide expert testimony in the case or one whose duties as the party's employee regularly involve giving expert testimony. The report must contain: (i) a complete statement of all opinions the witness will express and the basis and reasons for them; (ii) the datafacts or other informationdata considered by the witness in forming them; (iii) any exhibits that will be used to summarize or support them; (iv) the witness's qualifications, including a list of all publications authored in the previous 10 years; (v) a list of all other cases in which, during the previous four years, the witness testified as an expert at trial or by deposition; and (vi) a statement of the compensation to be paid for the study and testimony in the case. (C) Witnesses Who Do Not Provide a Written Report. Unless otherwise stipulated or ordered by the court, if the witness is not required to provide a written report, this disclosure must state: (i) the subject matter on which the witness is expected to present evidence under Federal Rule of Evidence 702, 703, or 705; and (ii) a summary of the facts and opinions to which the witness is expected to testify. (D) Time to Disclose Expert Testimony. A party must make these disclosures at the times and in the sequence that the court orders. Absent a stipulation or a court order, the disclosures must be made: 215 Mid•Level Professional development Program (i) at least 90 days before the date set for trial or for the case to be ready for trial; or (ii) if the evidence is intended solely to contradict or rebut evidence on the same subject matter identified by another party under Rule 26(a)(2)(B) or (C), within 30 days after the other party's disclosure. (D) Supplementing the Disclosure. The parties must supplement these disclosures when required under Rule 26(e). **** Rule 26(b)(4) Trial Preparation: Experts. (A) Deposition of an Expert Who May Testify. A party may depose any person who has been identified as an expert whose opinions may be presented at trial. If Rule 26(a)(2)(B) requires a report from the expert, the deposition may be conducted only after the report is provided. (B) Trial-Preparation Protection for Draft Reports or Disclosures. Rules 26(b)(3)(A) and (B) protect drafts of any report or disclosure required under Rule 26(a)(2), regardless of the form in which the draft is recorded. (C) Trial-Preparation Protection for Communications Between a Party's Attorney and Expert Witnesses. Rules 26(b)(3)(A) and (B) protect communications between the party's attorney and any witness required to provide a report under Rule 26(a)(2)(B), regardless of the form of the communications, except to the extent that the communications: (i) relate to compensation for the expert's study or testimony; (ii) identify facts or data that the party's attorney provided and that the expert considered in forming the opinions to be expressed; or (iii) identify assumptions that the party's attorney provided and that the expert relied on in forming the opinions to be expressed. (D) Expert Employed Only for Trial Preparation. Ordinarily, a party may not, by interrogatories or deposition, discover facts known or opinions held by an expert who has been retained or specially employed by another party in anticipation of litigation or to prepare for trial and who is not expected to be called as a witness at trial. But a party may do so only: (i) as provided in Rule 35(b); or 216 American Bankruptcy Institute (ii) on showing exceptional circumstances under which it is impracticable for the party to obtain facts or opinions on the same subject by other means. (CE) Payment. Unless manifest injustice would result, the court must require that the party seeking discovery: (i) pay the expert a reasonable fee for time spent in responding to discovery under Rule 26(b)(4)(A) or (BD); and (ii) for discovery under (BD), also pay the other party a fair portion of the fees and expenses it reasonably incurred in obtaining the expert's facts and opinions. 217 American Bankruptcy Institute The 2010 Amendments to Rule 26 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure Related to Expert Witnesses By Bonnie Steingart and Nathan Grow In 2010 the Supreme Court of the United States approved amendments to Rule 26 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure that affected expert testimony disclosure requirements and the availability of discovery related to expert testimony. Under these amendments, which took effect on December 1, 2010 (the “2010 Amendments”), certain expert witnesses that previously had no obligation to produce written materials are now required to provide a summary disclosure regarding their anticipated expert testimony. Further, the 2010 Amendments place restrictions on parties’ ability to obtain draft expert reports and certain communications between attorneys and expert opinions through discovery. There are two types of proceedings in bankruptcy cases: adversary proceedings and contested matters. Under Rule 7026 of the Federal Rules of Bankruptcy Procedure, Rule 26 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure is applicable in adversary proceedings. Under Rule 9014(c) of the Bankruptcy Rules, unless the court orders otherwise, Civil Rule 26(a)(2) (disclosures regarding expert testimony) is not applicable in contested matters. Under Bankruptcy Rule 9032, where Civil Rules are incorporated in the Bankruptcy Rules, any amendments to the Civil Rules are also made applicable. The following is a description of 2010 Amendments and the basis therefore as indicated in the Advisory Committee Notes. A blackline of the relevant provisions of Rule 26 showing the 2010 Amendments is annexed hereto as Exhibit A. Expert Testimony Disclosure Requirements Expert witnesses may be divided into three categories for purposes of determining their obligation to prepare materials regarding their expert opinion: reporting experts, non-reporting experts and non-testifying experts. Reporting experts are expert witnesses that are “retained or specially employed to provide expert testimony in the case or one whose duties as the party’s employee regularly involve giving expert testimony.” Fed. R. Civ. P. 26(a)(2)(B) (2012). Under Rule 26(a)(2)(B) (both before and after the 2010 amendments), reporting experts are required to file a detailed report including several enumerated elements. See Fed. R. Civ. P. 26(a)(2)(B)(i)--(vi). In adversary proceedings in bankruptcy court, investment bankers and others commonly testify as reporting experts as they are often specially retained to provide expert testimony on specific topics, such as on valuation and insolvency issues in fraudulent conveyance proceedings, and Rule 26(a)(2) applies in such proceedings. However, in contested matters in bankruptcy court, such as contested plan confirmation hearings in chapter 11 cases, though investment bankers often testify on such issues as valuation, restructuring options, and financial outlook, the filing of expert reports is not required in such contested matters unless the bankruptcy court, pursuant to Bankruptcy Rule 9014(c), so orders or directs the application of Rule 26(a)(2). 219 Mid•Level Professional development Program Non-reporting experts are any other expert witnesses that the party wishes to have testify during trial that are not “retained or specially employed to provide expert testimony in the case or one whose duties as the party’s employee regularly involve giving expert testimony.” Fed. R. Civ. P. 26(a)(2)(B). For example, in bankruptcy cases, an officer of the debtor (such as a chief financial officer or a chief restructuring officer) may provide expert testimony as a non-reporting expert given that such officers are usually not employed to provide expert testimony and do not regularly provide expert testimony as part of their job duties. If the officer is also an investment banker or financial advisor and was retained for the purpose of providing expert testimony, then the officer may be a reporting expert. The third category of expert witnesses is non-testifying experts who may be consulted by parties or their attorneys but do not offer testimony during trial. For example, a debtor’s counsel may consult with an expert in the debtor’s industry or an individual with expertise in public offerings in order to understand options for the debtor moving forward. Rule 26 (both the current version and the version before the 2010 Amendments) contains no requirement for nontestifying experts to prepare reports or disclosures. Work performed by non-testifying experts is generally not discoverable because it is covered by the attorney work product doctrine. Note, however, that if a testifying witness relies on the work of a non-testifying expert as the basis for the testifying witness’s testimony, that may open up the non-testifying expert’s work product and communications to discovery. As with anything else that is protected by the attorney work product doctrine, attorneys must exercise caution to protect non-testifying expert’s work from becoming discoverable. Discovery Related to Expert Testimony Prior to the 2010 Amendments, Rule 26(a)(2)(B)(ii) required that expert witness reports include the “data or other information” considered by the witness in forming the witness’ expert opinion. Fed. R. Civ. P. 26(a)(2)(B)(ii) (before 2010 Amendments). Courts interpreted “other information” broadly and allowed parties to request information relied on by expert witnesses through discovery, including communications between attorneys and expert witnesses. Limitation to “Facts or Data” The 2010 Amendments changed Rule 26(a)(2)(B)(ii) to require only “the facts or data” considered by the witness in forming the witness’s expert opinion. Fed. R. Civ. P. 26(a)(2)(B)(ii) (2012). According to the Advisory Committee Notes, the amendment is intended to alter the outcome in cases that have relied on [the pre-amendment] formulation in requiring disclosure of all attorney-expert communications and draft reports. . . . The refocus of disclosure on “facts or data” is meant to limit disclosure to material of a factual nature by excluding theories or mental impressions of counsel. At the same time, the intention is that “facts or data” be interpreted broadly to require disclosure of any 2 220 American Bankruptcy Institute material considered by the expert, from whatever source, that contains factual ingredients. Fed. R. Civ. P. 26 Advisory Committee’s Note. Work-Product Protection for Communications The 2010 Amendments also added Rule 26(b)(4)(C) which limits discovery of “communications between the party’s attorney and any witness required to provide a report under Rule 26(a)(2)(B)” (i.e. reporting experts). Fed. R. Civ. P. 26(b)(4)(C). In effect this means that work-product protection is afforded to certain attorney-expert communications. Parties are only allowed to request discovery of the following three types of communications between attorneys and reporting experts: (i) communications that “relate to compensation for the expert’s study or testimony” Fed. R. Civ. P. 26(b)(4)(C)(i); (ii) communications that “identify facts or data that the party’s attorney provided and that the expert considered in forming the opinions to be expressed” Fed. R. Civ. P. 26(b)(4)(C)(ii); and (iii) communications that “identify assumptions that the party’s attorney provided and that the expert relied on in forming the opinions to be expressed.” Fed. R. Civ. P. 26(b)(4)(C)(iii). According to the Advisory Committee Notes, discovery of communications on subjects outside the above three categories may be available in limited circumstances and by court order. “A party seeking such discovery must make the showing specified in Rule 26(b)(3)(A)(ii) — that the party has a substantial need for the discovery and cannot obtain the substantial equivalent without undue hardship. It will be rare for a party to be able to make such a showing given the broad disclosure and discovery otherwise allowed regarding the expert’s testimony.” Fed. R. Civ. P. 26 Advisory Committee’s Note. Notably, the new Rule 26(b)(4)(C) applies only to communications with reporting expert witnesses. There is no restriction on parties requesting discovery of communications between a party’s attorney and a non-reporting expert witness, however, there may be other privileges that apply to such communications. Previously, parties were permitted to request discovery of all communications between attorneys and expert witnesses. Led by the desire to avoid producing discoverable communications, parties frequently felt compelled to employ a reporting expert to testify at trial and a separate non-testifying expert for consultation. Attorneys would then discuss more sensitive and confidential case analysis with the non-testifying expert while limiting discoverable communications and the exchange of draft reports with the reporting expert. This dynamic created increased costs for parties and impeded effective communication. The Advisory Committee stated that the addition of Rule 26(b)(4)(C) was intended to “protect counsel’s work 3 221 Mid•Level Professional development Program product and ensure that lawyers may interact with retained experts without fear of exposing those communications to searching discovery.” Id. Work-Product Protection for Draft Reports In addition to protecting certain communications between attorneys and expert witnesses, the 2010 Amendments added Rule 26(b)(4)(B), which explicitly prohibits discovery of “drafts of any report or disclosure required under Rule 26(a)(2), regardless of the form in which the draft is recorded.” Fed. R. Civ. P. 26(b)(4)(B). This means that work-product protection is also afforded to draft expert reports prepared by reporting expert witnesses as well as draft disclosures prepared by non-reporting expert witnesses. Previously, courts generally allowed parties to request draft reports and thus discern whether an expert witness’s opinion changed or evolved during the time that the report was prepared and whether an attorney may have drafted or influenced portions of the report. Changes to Disclosure Requirements for Non-Reporting Experts Prior to the 2010 Amendments, there was no requirement for non-reporting expert witnesses to submit any written materials in connection with their expert testimony. The 2010 Amendments added Rule 26(a)(2)(C), which requires non-reporting experts to prepare a more limited “disclosure” setting forth “(i) the subject matter on which the witness is expected to present evidence under Federal Rule of Evidence 702, 703, or 705; and (ii) a summary of the facts and opinions to which the witness is expected to testify.” Fed. R. Civ. P. 26(a)(2)(C). Prior to the 2010 Amendments, courts occasionally imposed disclosure requirements on non-reporting experts in order to prevent the tension caused by the prospect of unexpected testimony during trial. According to the Advisory Committee Notes, the inclusion of Rule 26(a)(2)(C) was intended to resolve that tension. Fed. R. Civ. P. 26 Advisory Committee’s Note. Further, the Advisory Committee stated that a non-reporting expert’s “disclosure is considerably less extensive than the report required by Rule 26(a)(2)(B). Courts must take care against requiring undue detail, keeping in mind that these witnesses have not been specially retained and may not be as responsive to counsel as those who have.” Id. Application of 2010 Amendments in Selected Recent Cases In re Asbestos Prods. Liab. Litig., Civ. No. MDL 875, 2011 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 143009 (E.D. Pa. Dec. 13, 2011) In this case, the attorneys for plaintiff asbestos claimants sent letters to doctors with information regarding certain individuals’ exposure and medical history, which the doctors may have utilized in forming letters or reports to counsel to support a claim. The defendants requested discovery of these letters. The plaintiffs argued that the letters were protected under new Rule 26(b)(4)(B) because they were draft reports. However, the court ruled that the letters fell under the exception to the work product doctrine set forth in new Rule 26(b)(4)(C)(ii) because they constituted “facts or data that the party’s attorney provided and that the expert considered in forming the opinions to be expressed.” 4 222 American Bankruptcy Institute The court explicitly endorsed the view expressed in a law review article which stated, One final unanswered question is whether counsel will be able to use Rule 26(b)(4)(B) to trump Rule 26(b)(4)(C)(ii-iii)—can counsel protect from discovery facts or data considered by or assumptions relied upon by a retained expert by providing some in a draft report. Courts would not seem to be receptive to such an obvious loophole, and caution dictates against embarking upon such a course without the support of new case law in support of such a practice. George Lieberman, “Experts and the Discovery/ Disclosure of Protected Communication,” 78 Defense Counsel Journal 220, 227 (Apr. 2011). Allstate Ins. Co. v. Nassiri, 2:08-cv-00369-JCM-GWF, 2011 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 79866 (D. Nev. July 20, 2011) The plaintiff insurance company assigned an employee the task of determining the amount of damages incurred by the plaintiff in anticipation that the employee would testify as an expert witness. Testifying as an expert witness was not a part of the employee’s regular duties. The defendants argued that the employee should be required to prepare a report under Rule 26(a)(2)(B) rather than a summary disclosure under Rule 26(a)(2)(C). The court found that the expansion of the requirements for non-reporting experts in the 2010 Amendments militated toward requiring less of expert witnesses that were not retained specifically to provide expert testimony. Therefore, the court ruled that the witness was only required to provide a more limited disclosure under Rule 26(b)(2)(C). In re Application of Republic of Ecuador, 280 F.R.D. 506, 508 (N.D. Cal. 2012) The court ruled that communications between counsel and an expert’s assistants concerning the expert’s testimony are protected under the work product doctrine to the extent provided in Rule 26(b)(4)(C). However, communications between an expert witness and another expert (whether testifying or non-testifying) are not protected. Further, the court ruled that materials prepared by the expert’s assistants for use in an expert report are protected under Rule 26(b)(4)(B). However, materials prepared by nonattorney employees of one of the parties for an expert report are not protected under Rule 26(b)(4)(B) and must be produced. The court ordered the party that retained the expert to produce (1) “[n]otes, outlines, memoranda, presentations, reviews and letters . . . including those incorrectly labeled as ‘draft reports’” that were drafted by the expert, his assistants, non-attorney employees and non-retained experts; (2) “[c]ommunications between [the expert and his assistants] and non-attorney . . . employees, even where an attorney is copied”; (3) 5 223 Mid•Level Professional development Program “[c]ommunications between [the expert and his assistants] and third party expert consultants or those among third party consultants and . . . employees”; and (4) “[c]ommunications between [the expert and his assistants] and other . . . testifying experts.” Id. at 516 In making this ruling, the court stated as follows: The work product doctrine is to be narrowly construed as its application can derogate from the search for the truth. The party seeking to invoke the work product doctrine bears the burden of establishing all the requisite elements, and any doubts regarding its application must be resolved against the party asserting the protection. . . . If the rules committee intended to protect from disclosure all expert information prepared in anticipation of litigation, it would not have refashioned section 26(b)(4) specifically to address expert discovery. As the Advisory Committee notes to the 2010 amendments reveal, work product protection is limited to communications between an “expert witness required to provide an expert report under Rule 26(a)(2)(B) and the attorney for the party on whose behalf the witness will be testifying.” Id. at 514-15 (internal quotations and citations omitted). Decena v. Am. Int’l Cos., Civ. No. 11-1574, 2012 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 61303 (E.D. La. May 1, 2012) The defendant insurance company designated a doctor as a reporting expert witness and later notified the plaintiff that the doctor would be retained solely as a non-testifying, consulting expert and would not prepare an expert report nor be produced for a deposition. The plaintiff moved to compel the defendant to produce the doctor for a deposition. The court ruled that parties are not required to produce non-testifying experts for deposition, even where such experts have been previously designated as reporting experts. In making this ruling, the court noted as follows: [T]here is no consensus of authority as to whether an expert initially designated as a testifying expert witness, but later designated as a non-testifying expert before the disclosure of her expert report, may nonetheless be deposed as a testifying expert under FED. R. CIV. P. 26(b)(4)(A). The principal case on which Plaintiff relies, House v. Combined Insurance Co. of America, 168 F.R.D. 236 (N.D. Iowa 1996), has been described as representing the “minority approach” with respect to this issue. In contrast, the majority of courts to have addressed the issue have held that a 6 224 American Bankruptcy Institute party is only entitled to depose a non-testifying expert -- even when the expert had previously been designated as a testifying expert -- upon a showing of “exceptional circumstances,” as required under Fed. R. Civ. P. 26(b)(4)(B). The courts adopting the majority rule have almost universally concluded that the purposes of Rule 26 are better served by requiring a party to show “exceptional circumstances” to depose a non-testifying expert. As these courts have noted, the purpose of Rule 26(b)(4)(A) is to ensure a party’s ability to properly prepare to effectively cross examine his opponent’s experts at trial. Rule 26(b)(4)(B), in contrast, is intended to prevent one party from being able to benefit from his opponent’s trial preparation. Where an expert will not testify at trial, the purposes of Rule 26(b)(4)(A) are not served by allowing his opponent to depose the expert, as there is no need to prepare for cross-examination. Furthermore, permitting the deposition of a non-testifying expert will, in most cases, frustrate the purposes of Rule 26(b)(4)(B) by essentially allowing a party to utilize his opponent’s expert’s opinions to prepare his own case, and at his opponent’s expense. Id. at 4-7 (internal citations ommitted). 7 225

© Copyright 2025