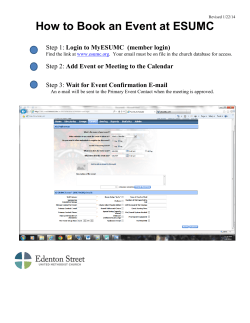

CSB W P