Help Wanted How to Hire The Best Teachers

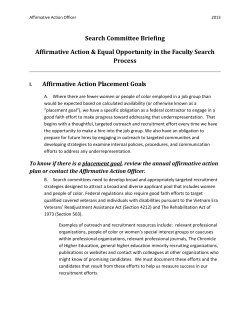

Help Wanted How to Hire The Best Teachers An interviewing technique borrowed from the business world can help principals decide which candidates make the best new hires. B Y M ARY C. C LEMENT 16 P R I N C I PA L L E A D E R S H I P very time you interview a candidate for a position at your school, you probably ask yourself, “Can this person really do the job?” The looming teacher shortage makes you wonder, “Even if this candidate lacks certain experience, will he or she be able to attain a satisfactory level of job performance?” If a candidate seems somewhat stronger, you may find yourself asking, “Will this candidate stay at my school long enough to grow into a master teacher who can lead others?” If time and money were not barriers, principals could spend time in the classrooms of student teachers and watch them teach, evaluating first-hand which candidates would make the best new hires. If technology were a perfect tool, candidates could be evaluated by means of videos or “realtime” cameras placed in their classrooms. If you had hours to read portfolios and evaluate those colorful four-inch binders that student teachers now produce, you would have a strong indication of the kind of lesson plans, activities, PHOTO BY COMSTOCK IMAGES units, and tests the candidates were capable of producing. However, the real world gives us time and budget constraints, and the truth is that the on-site interview will probably remain the most useful tool for determining which candidates receive job offers. Although the job interview has always been used as a tool for sorting and ranking the best candidates for jobs, it may now be viewed as an early step in recruiting the strongest candidates to your school and in retaining teachers. Expectations of a Position When an opening occurs at your school, envision the new position by identifying the job skills an effective teacher will need. Whenever possible, do not give the new teacher the most challenging classes, smallest room, or multiple preparations. Practice “truth in advertising” about a position. If the opening is for a teacher of remedial students or for classes with large numbers of special education students, include that information in the job description and discuss it openly in the interview. Often, a teacher who leaves a position remarks, “It just wasn’t what they told me it would be in the interview.” Candor in the interview should make expectations very clear to the candidate. When interviewing prospective teachers, a middle level principal told interviewees that teaching at her school might be considered a little like working in the Peace Corps because it could easily be “the toughest job you’ll ever love.” Her straightforward attitude in interviews eliminated some candidates quickly through self-selection, but those who joined the staff felt they had been chosen to do important and significant work. Feeling needed and appreciated for the job of teaching is an incentive for idealistic teachers, and this technique is a recruitment and retention tool that costs no money. Preliminary Review Teacher retention often depends on whether the candidate is a capable teacher and whether the candidate is qualified for SEPTEMBER 2002 17 the position. When reviewing candidates’ paperwork before the interview, the first criterion to sort by is the question, “Is this candidate certified or not?” Although a debate continues to rage about whether certification equals qualification to teach, teaching-certification standards are currently the best available measure for assessing whether candidates are qualified to teach. When at all possible, consider only candidates who are certified in the fields for which they will teach. Of course, in times of teacher shortages, some districts must turn to noncertified teachers or those who are provisionally certified so all classes will be covered when the new school year begins. If your school’s geographic location, intense jump in enrollments, or lack of a pool of certified applicants forces you to consider provisionally certified personnel, plan for their continued training toward certification. During interviews, inform candidates of the district’s policies about their progress toward certification and discuss the termination of their employment if they do not meet state guidelines for certification within given time frames. Put these guidelines in writing so candidates with provisional certification know every step they must complete for initial hiring and continued employment. The first years of teaching can be very stressful for any new teacher, and those new teachers who must attend evening classes to complete their certification will possibly have less free time and more stress than other new hires. Plan their induction and support accordingly and explain your school’s programs in the interview. Candidates can accept clearly expressed expectations. New hires who leave the classroom quickly are those who say, “But nobody told me,” and “I didn’t know I had to do that.” U nlike traditional interview- ing that begins with “tell me about yourself” and asks hypothetical questions, in behaviorbased interviews, candidates describe specific past experiences and how they dealt with and learned from those experiences. Tips from the Business World Historically, certain sectors of the business world have dealt with employee shortages and high employee turnover. To be competitive, businesses with those concerns have sometimes been able to raise salaries or improve workplace conditions. In addition, the business world has developed behavior-based interviewing as a means of hiring the best new employees. Defined by Janz, Hellervik, and Gilmore (1986), this strategy is based on the premise that past behavior is the best predictor of future performance. Unlike traditional interviewing that begins with “tell me about yourself ” and asks hypothetical questions, in behavior-based interviews, candidates describe specific past experiences and how they dealt with and learned from those experiences. Richard Deems (1994) reminds us that “The single best predictor of a candidate’s future job performance is his or her past job behavior” (p. 9). He has found that the 18 P R I N C I PA L L E A D E R S H I P behavior-based interview is a more reliable predictor of a candidate’s ability than an interview focused on personality traits. Principals who have interviewed elementary education majors know that almost all candidates say, “I want to be a teacher because I love children.” Although this is a commendable trait, it doesn’t help the principal sort the candidates; questions about specific past experiences will. The Basics of Behavior-Based Interviewing Two acronyms guide behavior-based interview questions: PAR and STAR. PAR refers to the formula of asking about a problem, an action, and a result. For example, an interviewer asks a candidate, “Tell me about a time when you had to deal with a large number of students in a small space.” The candidate, who has experience with larger classes, talks about student teaching 31 students in grade 7 in a small classroom. The candidate describes how she and her cooperating teacher designed a seating chart and used a table near the door for students to pick up their journals for class as they entered the classroom. The candidate concludes that as a result of the new plan, the students wasted less time at the beginning of every class. An interviewer can rate this answer very highly. Here is a candidate who has experience working successfully with larger classes, who worked creatively with her cooperating teacher, and who knows that students in large classes must have a process in place to get into the room and get settled. When faced with a class of 30 middle level students, this candidate should know how to organize her room to accommodate them. The acronym STAR refers to asking questions about a situation, a task, an action, and a result. Because grading is a significant task for all teachers, an interview question could be “How have you dealt with assigning grades in high school English classes that required many writing assignments?” A candidate should be able to describe how he or she taught writing in the classroom and how grading was handled. A strong candidate should be able to describe how rubrics were used for individual assignments and how the grades were averaged using a grade-book software program. An exceptional candidate might elaborate on how learning Sample Interview Questions These questions are generic enough in nature that they fit teacher interviews for almost any grade or subject level. Use them as a starting point for developing a personalized list of questions. For each advertised position, some of the questions will be made more specific. For example, ask a candidate for a first-grade position to describe his or her experiences in teaching phonics or ask a candidate for a middle level math position to describe how calculators can be used in the classroom. For the sake of fairness, it is important that each candidate for the same position be asked the same set of questions. (For lists of other questions, see Building the Best Faculty [Clement, 2000] and Essentials for Principals [Clement, D’Amico, & Protheroe, 2001].) Curriculum Meeting Individual Students’ Needs 1. How have you decided what to teach to your class in the past? 2. What have you used from the national and state standards to guide your teaching? 3. What are important curricular topics for this grade or subject? 1. Describe an approach to teaching your subject that has helped all students succeed. 2. What have you done in past classes to promote acceptance, tolerance, and cultural diversity in your classroom? 3. What modifications have you made to assist special education, language minority, or gifted students in your classroom? Planning 1. Describe a successful unit you have taught. 2. Describe a typical lesson plan that works well for you. 3. Tell me about a time when one of your lessons ran short or when you ran out of time. What did you do? 4. What are good techniques for beginning and ending your class? Classroom Management and Discipline 1. Describe rules, consequences, and rewards that work for students in this grade. 2. Tell me about a time when a student confronted you or attempted to break school classroom rules. How did you handle this? 3. Describe the arrangement of your classroom. If I were to walk in, what would I see that helps keep students organized? Homework, Grading, and Assessment 1. How do you assess student learning informally without grading? 2. Tell me about a typical homework assignment for this class. 3. How have you dealt with students who turn in homework late or not at all? 4. Describe a grading system that has worked well for you in the past. Communication With Parents and Others 1. Describe a positive way to communicate with parents that you have used in the past. 2. Describe a parent conference that you have conducted and the results from it. 3. Tell me about a time when you cotaught a class or planned an activity with a colleague. Professional Growth 1. What have you read or studied recently that led to a change in your teaching? 2. What par ts of your teacher education program do you most often use? 3. Describe what you learned in the past from a cooperating teacher or mentor teacher. References ❏ Clement, M. C. (2000). Building the best faculty: Strategies for hiring and supporting new teachers. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press. ❏ Clement, M. C., D’Amico, J. J., & Protheroe, N. (2001). Essentials for principals: How to interview, hire, and retain high-quality new teachers. Alexandria, VA: National Association of Elementary School Principals. SEPTEMBER 2002 19 PHOTO BY DIGITAL VISION Share details of your induction opportunities with candidates during the interview, reminding them of the support and help available at your school. this grading system during student teaching enabled him or her to help the cooperating teacher determine which seniors were eligible for honor society. Both PAR and STAR help the interviewer remember to phrase the questions in a manner that calls for past experiences to be explained. This is more useful in evaluating candidates than asking hypothetical questions or questions about personality traits or feelings. Specific Interview Questions Although the field of education can borrow the practice of behavior-based interviewing from the business world, the specific questions designed for the teaching interview will be unique ones. After a brief icebreaker or warm-up question, the interview should consist of questions about the topics that represent effective teaching. Effective teachers know their subject matter and how to organize it into appropriate lessons and units, so the interviewer must ask about curriculum. Good teachers plan for instruction and manage the classroom environment and student behavior, so the interviewer should ask planning and management questions. Homework, grading, and assessment are vitally important in today’s climate of teacher accountability, so questions on those topics must be asked. Although 20 P R I N C I PA L L E A D E R S H I P it is easy for candidates to say that “all children can learn,” candidates should be asked how they will address meeting individual student needs, including the needs of language minority children and those in special education. All teachers work in the public eye, therefore a teacher’s ability to communicate with parents is important. Because teachers can be viewed as public relations personnel for their schools, some questions should address the candidate’s past experience with parents, as well as his or her ability to deal with colleagues and administrators. Finally, teachers are professionals and professionals stay current in their field, so the interviewer should prepare some questions for evaluating the candidate’s professional development. The Candidate’s Responses Before you ask interview questions, think about how you will determine whether an answer is strong, acceptable, or weak. You may want to create a rating scale for your answers, or simply write down S, A, or W beside each question and two or three words to remind you of the candidate’s response when you review the interview with other supporting paperwork. In many districts, the principal is no longer the only interviewer. Personnel directors and representatives from I nduction and retention begin at the end of the interview. All schools should have planned professional development for their new teachers that includes orientation before school starts, ongoing support seminars during the school year, and a mentoring program. human resources may conduct initial interviews at job recruitment fairs. Committees of teachers may interview a candidate and make a recommendation to the principal and the personnel director. If your district uses teacher committees in interviews, make sure that all teachers receive necessary training and orientation about hiring processes (Nuzum, 2002). Office support staff members also need orientation regarding illegal interview questions and confidentiality matters. Recruiting Through Interviewing Although you are trying to decide which candidate is best for a position, the candidate is also trying to decide which school will be best for him or her. Your district’s response to the candidate’s submission of a cover letter and résumé should be timely. A form letter can be sent, along with a checklist that informs the candidates whether they still need to submit transcripts, letters of recommendation, a district application, or other paperwork. Candidates appreciate having the name and phone number of one person who can answer their questions. When setting up interviews, tell the candidates with whom they will be interviewing and whether the interview will be conducted by a committee. Letting candidates know the specifics about when to arrive, where to go, and what to bring (e.g., portfolio, video, supporting paperwork) will also help make candidates feel at ease. Candidates who feel that the interviewer had time for them also feel that the school will have time to support their work. Candidates want to feel as if they are being recruited into the business world, and every small token of time and attention given to them will encourage them to join your faculty. Supporting New Teachers Induction and retention begin at the end of the interview. All schools should have planned professional development for their new teachers that includes orientation before school starts, ongoing support seminars during the school year, and a mentoring program. Share details of your induction opportunities with candidates during the interview, reminding them of the support and help available at your school. Although money isn’t everything, new teachers are concerned about surviving financially. Some schools pay a stipend to new hires who attend a week’s worth of orientation sessions and training before the regular back-to-school workdays, and this stipend may help a new teacher on a tight budget. Arranging for the first year’s salary to be spread over 13 months instead of 12 may make a difference in a candidate’s decision to start teaching at your school as well. (A 13-month year provides a paycheck the first August through the following August, yet costs the district nothing extra.) The complete benefit package, including insurance for dependents and early retirement options, may be the deciding elements for some. Just as the education profession has adapted behaviorbased interviewing from the business world, so too should we consider other business examples. The quality of the workplace will always be a factor in attracting and keeping the best new teachers, so we must provide “the schools our teachers deserve” (Cohen, 2002). All teachers deserve a workplace that is professional in both its physical setting and its administrative support. Finally, many people enter the teaching profession with a sense of mission or from a sense of calling. Supporting this positive attitude in new teachers will not only help retain faculty but also may help the new teachers rejuvenate the veterans. An interview that asks about specific past experience and behavior should help to determine the candidate’s mission and calling, allowing you to hire the best qualified candidate for your faculty. PL References ❏ Cohen, R. M. (2002). Schools our teachers deserve: A proposal for teacher-centered reform. Phi Delta Kappan, 83(7), 532–537. ❏ Deems, R. S. (1994). Interviewing: More than a gut feeling. West Des Moines, IA: American Media Publishing. ❏ Janz, T., Hellervik, L., & Gilmore, D. C. (1986). Behavior description interviewing: New, accurate, cost effective. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. ❏ Nuzum, M. L. (2002). Preparing teachers for staffselection committees. Principal Leadership, 2(7), 20–24. Mary C. Clement (mclement@mindspring.com) is an assistant professor in the department of teacher education at Berry College in Georgia. Her teaching includes a graduate course in supervision, hiring, and mentoring for aspiring principals. SEPTEMBER 2002 21

© Copyright 2025