Funding challenges: How to finance expensive technologies in the context

EHRA Policy Conference Athens, December 13th 2011 Funding challenges: How to finance expensive technologies in the context of limited resources Giuditta Callea Cergas - Bocconi University, Milan, Italy www.together4healthinnovation.eu “Stemming the global tsunami of cardiovascular diseases”, Lancet, 2011 • 2 billion people are at risk of cardiovascular diseases: o 1.3 billion smokers o 600 million hypertensive o 220 million diabetics. 2 “Forecasting the Future of Cardiovascular Disease in the US”, Circulation, 2011 • Currently, CVD is the leading cause of death in the US and constitutes 17% of the overall national health expenditures. • By 2030, 40.5% of US adults (116 million people) will have one or more forms of CVD. • • • Between 2010 and 2030, total direct medical costs are projected to triple, from $273 billion to $818 billion. Indirect costs due to productivity loss are estimated to increase from $172 billion in 2010 to $276 billion in 2030 (+61%). Projected Direct and Indirect Costs of CVD, 2010 to 2030 in the US (in Billions 2008$) 1 200 1 000 276 800 600 400 200 - 172 196 220 273 358 470 2010 2015 2020 246 622 2025 818 2030 Direct (Medical) Costs of CVD Indirect (Lost Productivity) Costs of CVD These projections do reflect the demographics of an ageing population. 3 In 2010, over 1/3 of EU’s population has developed at least one chronic disease 4 Economic burden of CVD in EU-27, European Heart Journal, 2006 Cost of CVD (in Billions 2003€) 168 105 63 29 CVD Informal care 34 Production losses 28 Healthcare costs Medications 14 Inpatient care Promary & outpatient care 5 Pacemakers: units per million inhabitants 6 Defibrillators: units per million inhabitants 7 CRT-P: units per million inhabitants 8 CRT-D: units per million inhabitants 9 Good clinical evidence is not enough any longer • Over the past decades, the quality of clinical evidence has become the primary criterion for accepting and funding technologies. • Nowadays increasing concerns around healthcare costs escalation: o The proportion of elderly is increasing 2030 2010 > 65 < 65 > 65 16% 84% • < 65 24% 76% o The incidence of chronic conditions increases o Public resources as from fiscal revenues necessarily decrease: fewer people would cover a greater number of more costly people. Necessity to combine clinical effectiveness to economic efficiency. 10 Where is Economics…in principle? • Healthcare decision-making level. • Bring evidence to the policy makers: o Health Technology Assessment 11 Health Technology Assessment • HTA is a multi-disciplinary process studying the medical, economic, social and ethical implications of diffusion and use of health technology aimed at informing policy-decisions to efficiently allocate scarce resources. • Economic Efficiency and Clinical Effectiveness dominate HTA activities and Cost-Effectiveness Analysis normally makes the most of HTAs. • CEA decision rule: Incremental Cost-Effectiveness Ratio (ICER). ICER = CB CA EB EA 12 Are (current) CEAs & ICERs good proxies for cardiac devices values? • Since the 90s there has been significant innovations in the cardiology sector (e.g. balloon angioplasty, coronary stents, ICDs, TAVI, mitra-clip, ...). • Nevertheless a systematic review* on economic evaluation studies of cardiac devices (i.e. ICDs, pace-makers, stents) over the period early 1990-2009 shows poor results: o 5% examined long-term benefits o 15% used QALYs o Cost of device at uptake primary cost driver: No consideration for learning curves No organisational impact. *Sorenson et al., Applying Health Economics for Policy Decision Making: Do Devices differ from Drugs?,2011, Europace, Vol. 13 (suppl. 2), pp. ii54-ii58. 13 Are (current) CEAs & ICERs good proxies for cardiac devices values? NO • Adapting CEAs for pharmaceuticals to devices gives a partial picture of the true costs and benefits. • Drugs differ from devices: o • Evidence is growing (Drummond et al., 2009; Sorenson et al., 2010; Tarricone & Drummond, 2011) but needs support by clinicians to contribute to the debate (e.g. 2nd Join-Action by EC). RCTs do not work sufficiently for MDs: o • Registers need to become more reliable and credible. Benefits should encompass a wider perspective: o Productivity gains by patients & informal care givers o Returns on the economy (R&D, competitiveness, qualified employees, …) through the multiplier effect of MedTech. 14 What might happen then? • We would measure the true “opportunity cost” of allocating scarce resources in programmes other than healthcare. • Higher level debate might be engaged onto how and where to allocate global public budgets, providing that benefits healthcare programmes accrue to non-healthcare sectors also. 15 Is it out of reach? • John Dalli, “Better Health, Better Economy”, at Finnish Government (February, 2011). • German Ministry of Economic Affairs, “We must not only regard health care spending as a cost factor, but need the full economic perspective”: o Direct medical costs have increased by €101 billion in 2003-2008 vs. 2002. This is however counterbalanced by an avoided loss of gross national product by €123 billion in the same period, as a result of avoided loss of productive life years. o Medical progress has thus a positive net impact on the economy, as a result of lowered indirect costs such as productivity losses. 16 Where is Economics…in principle? • Healthcare decision-making level. • Bring evidence to the policy makers: o Health Technology Assessment o EHTI International Study “Linking Hospital Payments to Innovation and Value”. 17 Linking Hospital Payments to Innovation and Value: Research Team • LSE Health: Michael Drummond and Corinna Sorenson • Bocconi University: Aleksandra Torbica and Giuditta Callea • University of Lisbon: Ceu Mateus 18 Linking Hospital Payments to Innovation and Value: Background and Aims • Shift towards prospective payment schemes for hospitals in a wide range of countries. • Most new MDs are first introduced in the inpatient sector medical technology is strongly dependent on funding regulation. • Minimal available evidence that the value added by a device is used in determining payment levels. o • However, EHTI phase I research and the EuroDRG project both highlight that some countries use instruments (e.g., special payments) to provide extra payments for technological innovations. Thus, proposed research aims at identifying ways in which the additional value offered by devices can be directly reflected in payments. 19 Linking Hospital Payments to Innovation and Value: Research Questions • What are the characteristics of the reimbursement system (DRG system developed locally vs. imported from elsewhere, DRG rates developed at national vs. regional level, frequency of updates)? • What provisions exist for extra payments in various jurisdictions to facilitate the adoption of new devices? • Are there any hospital payment schemes in Europe and elsewhere that consider evidence of the value of new technologies when updating DRGs and/or tariffs? • How is such evidence considered or incorporated into adjusted payments? What are the challenges of this process? Who is involved? • In what ways could payment schemes be changed to more closely link payment levels to evidence on value? 20 Linking Hospital Payments to Innovation and Value: Components of the Study • Literature review. • International survey of experts involved with developing/administering prospective payment schemes o 14 countries represented: o • Australia, Austria, Canada, England, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, USA. 51 surveys disseminated, 33 returned to date (65% response rate). Semi-structured interviews in England and Italy with o Hospital managers (ongoing) o Clinicians (to be performed). 21 Linking Hospital Payments to Innovation and Value: Preliminary Results • Almost an even split between countries that developed their DRG system locally vs. importing/adapting it from elsewhere. • Most DRG rates/tariffs are defined on the national level, although in many countries, this is also done at the regional level. • Almost all countries update DRG rates/tariffs annually. • Minority of countries create a single DRG and rates/tariffs outside of a general update as a response to innovative technology. o In cases where they have been created, volume and cost are the principal criteria for a new code. 22 Preliminary Results of the International Survey: Use of Evidence of Value 4 14 Number of Countries 12 Therapeutic Benefit 10 8 Yes 6 No Uncertain CostEffectiveness (V4$) Both 2 4 2 0 0 Use of Evidence of Value If Yes, Type of Evidence Considered *Yes: England, France, and Portugal 23 Preliminary Results of the International Survey: Perceived Impact of DRGs on Uptake of Innovative Technologies Australia Austria Canada England Finland France Germany Ireland Italy Norway Portugal Spain Sweden US No impact Modest impact Moderate impact Significant impact Extremely Significant impact 24 Preliminary Results of the International Survey: Type of Impact • “Depends on how the tariff is set – too low and innovation is inhibited”. • “If no DRG specific to a given treatment, then use by clinicians can be limited”. • “DRG values in the US mostly encourage surgical/procedural innovations, which have high tariffs and now much in the medical DRGs (e.g., stroke) that have much lower tariffs”. • “Depends on the design of the DRG system. R&D as well as early innovation need to be funded as separate programmes”. • “Tariffs are set annually; hospitals ahead of the adoption curve take the risk that their higher costs will not be reimbursed in the first years – this slows adoption. But, as a medical innovation disseminates across the system, these costs are absorbed into the costings that form the basis of DRG tariffs,25 reflecting patterns of adoption”. 14 Number of countries 12 10 8 6 4 2 0 Type of Impact Encourage Inhibit Both No impact Linking Hospital Payments to Innovation and Value: Drawbacks of DRGs to Supporting Uptake and Diffusion of Innovation • Time lag between: o Introduction of the new MDs o Update of classification system: “The integration of innovation into the DRG tariff cannot be determined as long as there is no possibility to code the innovation separately” o • Update in DRG rates/tariffs Hospital motivation: o • “Generally, DRG systems lag behind in reflecting innovative health technologies, which are initially expensive, and therefore hospitals are unlikely to invest if they are primarily motivated by DRG payment in the short term”. Perspectives: o “A limited picture – one needs to consider the overall costs of the DRG. While a new technology may have a higher cost, it may result in a shorter LOS”. 26 Linking Hospital Payments to Innovation and Value: Special Payments • About 70% of countries surveyed use some form of special payment for specific technologies. o • • Most commonly in the form of payments in addition to the tariff or a payment negotiated outside of the DRG. Typical criteria for these payments include: o High costs o Defined specialist services/interventions or diagnoses o Level of activity (i.e., found in a number of DRGs) o New innovation. MoH and regional authorities/hospitals most often involved in determining or negotiating special payments. 27 Linking Hospital Payments to Innovation and Value: Use of Evidence of Value in Special Payments 6 14 Number of Countries 12 10 Therapeutic Benefit 4 8 CostEffectiveness (V4$) Both Yes No 6 2 4 2 0 0 Use of Evidence of Value *Yes: Australia, England, France, Germany, Portugal, Sweden, US If Yes, Type of Evidence Considered 28 Linking Hospital Payments to Innovation and Value: Special Payments Processes • In the majority of countries, it takes between 1-2 years to determine special payments. • Payments are generally reviewed annually and/or when a given technology can adequately be incorporated into an existing DRG. • All respondents deemed such payments an effective mechanism to integrate technologies into the health system. 29 Preliminary Results of the International Survey: Technologies Where Special Payments Have Been Applied Drug-eluting stents AU, EN, FR, DE, IE, IT Transcatheter Heart Valve (TAVI) AU, EN, FR Neuromodulation Implants EN, FR, NO, PT, IT Ambulatory Volumetric Pumps FR Gastric bands EN, FR, PT, SP Cochlear implants AU, FR, IE, NO, PT, SP, IT Hip prosthesis AU, FR, SP Knee prosthesis AU, FR, SP Bladder band FR 30 Conclusions • Very preliminary results. • Next steps: • o Complete interviews with hospital managers in England and Italy and analyze data. o Interview clinicians. If any of the participants to the EHRA Policy Conference is willing to contribute to the Research, please send an email to giuditta.callea@unibocconi.it to receive the questionnaire. 31

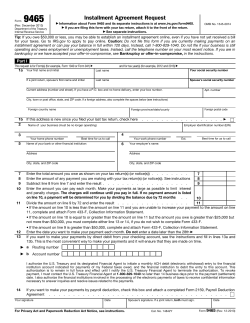

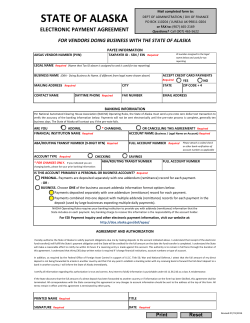

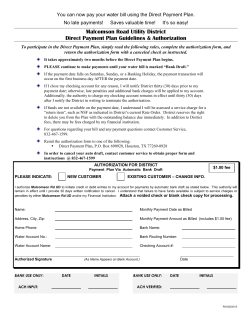

© Copyright 2025