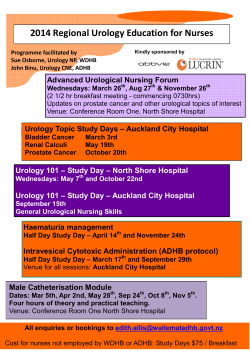

New Technologies in Urology