Document 205377

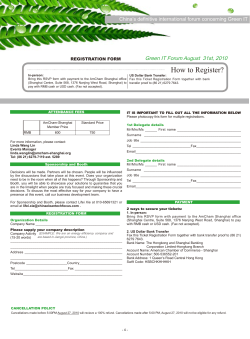

Report Public Education and Awareness How to put it into Practice Article 13 of the Convention on Biological Diversity Global Biodiversity Forum Workshop Bratislava, May 1998 Contents Workshop Report: Public Education and Awareness- Article 13How to put it into practice Pages Rationale Organisation Learning from the workshop on putting article 13 into practice Defining the issue Specific approaches for specific groups Understanding perceptions The role of government to “promote and encourage understanding” 1 2 3 4 6 The role of NGOs in Article 13 15 Lessons learned from managing networks to mobilise communities 18 International Co-operation and Article 13 19 Lessons learned in managing an educational program 21 Conclusions of the GBF workshop Participants 26 Public Education and Awareness - Article13 – How to put it into Practice Rationale For the first time, Article 13 on public education and awareness was discussed by the fourth Conference of the Parties, May 1998. Since many of the threats to biodiversity are a result of human action, public awareness and education need to play a large role if the Convention is to be successfully implemented. The Global Biodiversity Forum workshop aimed to bring up to date thinking on how Article 13 could be implemented and accordingly make recommendations to the Parties. Article 13 states that the Contracting Parties shall: (a) Promote and encourage understanding of the importance of, and the measures required for, the conservation of biological diversity, as well as its propagation through media, and the inclusion of these topics in educational programs; and (b) Cooperate, as appropriate, with other States and international organisations in developing educational and public awareness programs, with respect to conservation and sustainable use of biological diversity. Organisation The workshop was sponsored by the Ministry of Environment Norway, and chaired by Sylvi Ofstad Sontag, Deputy Director and CEC member. Around 50 participants attended from 23 countries representing NGOs, governments and indigenous people. Cases were presented that explored the role and principles for organising and managing education / communication programs for biodiversity conservation and sustainable use. What marked the workshop was a high degree of accord from the lessons learned and these are brought out in the following text. At the end of the workshop, participants developed key recommendations that arose from the papers and discussion. 1 Public Education and Awareness GBF Workshop Report Learning from the workshop on putting article 13 into practice Defining the issue: making biodiversity realistic and tangible The challenges facing biodiversity communication and education are:• • to make something boring and remote to most people, real and personally relevant. In other words, replace the feeling that “I can’t influence it anyway” to something personalised; make a large issue small enough to be solved, as biodiversity tends to be all inclusive and is hard to narrow down. Therefore, translate it from something complex to something easy to grasp. Change the issue from something unclear to a clear issue which can be evoked by a symbol or visual story; What is the nature of your issue? Impact on people business etc Complexity Strategic relevance Stakeholders Symbols & anecdote Awareness & interest Sensitivity (potential for conflict) Interface / relation to other issues Figure 1: Clarifying the nature of the issue from Hans Olav Otterlei • • • • to change the communication from wordy arguments about why biodiversity is important, to communicating what results are wanted; to use other more accepted issues as a way to lever interest in biodiversity like climate change for example; to access the hearts and minds of your target audience; concentrate on those that have high influence, either negative or positive, and spend little on those that have weak negative influence. 2 Public Education and Awareness GBF Workshop Report Not all audiences are equally im portant influence Negative positive Figure 2: Concentrate efforts on those that have the most positive and most negative influence. Hans Olav Otterlei The biodiversity issue is often expressed as a traditional management goal and must be clearly stated and kept in focus, since the communication or education program is an instrument to assist in attaining that goal. Management approaches often are ecosystem based; but when it comes to practical application it is sometimes easier to understand a problem in terms of species, populations, or habitats. Remember that what is about to be accomplished must be real and “do-able” to many people. Specific approaches for specific groups There is a widespread tendency to try to address biodiversity conservation issues through broad mass media campaigns to educate the public at large. A significant body of educational research presented at the workshop, disputes this approach. Rather than attempting to reach vast generalised public audiences, it emphasises the importance of designing educational initiatives for specific groups within specific contexts. This targeted approach has much in common with the concept of market segmentation in the corporate sector based on the argument that knowledge is dependent on context and actively constructed and reconstructed within the world of real practice. People’s thinking is intimately interwoven with the context of the problem to be solved so the program for a fisherman or an eco-tour leader is distinctly different. Programs designed to create a generalised understanding of biodiversity are therefore less effective than those targeted toward a specific biodiversity concept. Educational research also recognises that people learn when engaged on real projects, and exchange information with others. 3 Public Education and Awareness GBF Workshop Report Whose support do you need to gain •The more specific description of your audience, the better •What perceptions do you need to change? Current perception & behaviour Emotional & rational drivers and barriers Desired Perception & behaviour What is the “hot button” Figure 3: In applying marketing approaches to biodiversity issues it is essential to understand the target group’s current perception and behaviour and the barriers or drivers (emotional and rational) that stand in the way of a different perception and action. The hot button is the trigger to stimulate change. Hans Olav Otterlei Understanding perceptions - motivation People’s actions determine if biodiversity is conserved or is sustainably used. Those practices that degrade or destroy biodiversity ideally need to change, whereas positive practices need to be encouraged. Changing practices or behaviour is difficult as it can create hardship or inconvenience. What a person does depends on their intentions and attitudes which are shaped by many influences such as past experience, values, culture, personality, emotions, knowledge, and expectations. There is a general tendency to act as if the only important thing about learning is the manipulation of information in the learner’s mind. This fuels an erroneous assumption that action for biodiversity can be induced simply by presenting people with information about animals or environments and explaining the problems that confront them. Learning involves the senses, desires, longings, feelings and motivation, not just the mind. Attitudes, social relationships and social structures all play a role in how a person reacts to a situation, and determine the action they would take. Values and beliefs determine the attitudes people have. Values are standards that influence how people perceive fact and are used to guide action. Beliefs refer to what an individual perceives as knowledge and may be factual or based on personal opinion. People are not empty vessels waiting to be filled with new knowledge. Decades of educational research indicate that recipients of scientific knowledge are far from passive but interact with science, test it against personal experience, overlay it with local knowledge, and evaluate its 4 Public Education and Awareness GBF Workshop Report social and institutional origins. The idea of one way flow of information from scientist to public is inadequate. Perceptions colour what people hear, even amongst children. This demands that education encourages people to explore and challenge their own knowledge and beliefs about biodiversity in relation to accepted and socially held views. Reality therefore depends on how a person perceives it. Coming to terms with these different realities is part of any stakeholder negotiation, round table, or conflict resolution process. By working to better understand the different perceptions, people adjust their own world view and can find ways to develop a shared understanding or goal. The impact of different perceptions on conservation seriously affects the sustainable use of wildlife in southern Africa. Development is an imperative for people in southern Africa where people need to gain economic benefits from using wildlife. When benefits are clear there is more incentive to conserve wildlife, especially when as in the case of elephants they create serious damage to people’s gardens and livelihood. Yet conservation ideology from more developed western nations has set up a trading block for many of the species that can be harvested. This seriously reduces the income that can be derived from marketing wildlife products. To influence “northern“ perceptions an active communication program has begun. How do you plan your campaign? •What do you want to achieve (as specific as possible?) •What are the critical factors for success •What is your issue- how do you define the problem? •Which audiences will have to change in order for you to achieve your objectives? •What do they currently feel, think & do? •Who influences them? •What do we need them to think and act? •What can persuade them to change- what is the “hot button”? Figure 4 : Summary of the steps to work through for a campaign aimed at influencing perception and behaviour. Hans Olav Otterlei 5 Public Education and Awareness GBF Workshop Report The role of government to “promote and encourage understanding” Governments, as signatories to the Convention, have an obligation to promote and encourage understanding of the Convention and its measures. Public information to promote and encourage public understanding differs radically from press information provided by governments. The way countries inform their citizens depends often on the provisions of their Government Information Act. Information can be provided • in a reactive form, on request, or • in an active form to provide information on policy and policy plans, • through communication as a policy instrument, and • communication in the policy making process. Informing on policy and plans Informing the public about policy and policy plans has traditionally been one of the government’s main duties. The basic aim is to inform relevant groups within the general public as soon as this is required in order to ensure that the decision making process is both effective and depending on the country, democratic. Secondly, the aim of information once a policy is adopted, is to let people know what is expected of them and what they should do or not do. In the UK a consultation paper to key sectors has been produced. Information is disseminated through internet, newsletters and articles produced in government publications as well as in those of other organisations. High profile Ministerial launches are used to put issues on the agenda, and a postage stamp series has been released on endangered species along with an explanatory information sheet. E d ucation & P ub lic aw aren ess in th e U K - achiev em en ts • • • • • • • • • • G uidan ce n otes o n local b io diversity action plans internet site q uarterly n ew sletter co nsultatio n p aper for k ey secto rs p ub lication s / initiatives at co un try / reg io nal lev el h ig h pro file m in isterial laun ches B u siness & b io diversity d ocu m ent articles on b io diversity in N G O / g ov m ag azin es b io diversity p ostag e stam ps “ed ucatin g fo r life- ed ucatio n g uidelin es” Figure 5: UK achievements in biodiversity education as of May 1998: Graham Donald, Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions 6 Public Education and Awareness GBF Workshop Report Figure 6: The stamp set prepared for the UK on endangered biodiversity is accompanied by an information sheet listing all the endangered species in the United Kingdom. 7 Public Education and Awareness GBF Workshop Report Education & PA in the UKchallenges •Embed biodiversity throughout government at practical level •decide how biodiversity should be reflected in formal education in schools- curriculum •little general impact on business •large shopping list of good ideas- no priority or strategy •targeted approaches to “influencers” in key professions •local environment / biodiversity month in 1999 •seminar/ workshop involving DETR, DfEE & CEE Figure 7: UK challenges in biodiversity education and public awareness as of May 1998: Graham Donald, Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions Governments have obligations to prepare biodiversity strategies and actions plans to implement the Convention articles. In the UK, guidance notes on local biodiversity action plans have been issued to local authorities. Yet, many countries are experiencing difficulties because there is an inadequate understanding of biodiversity issues amongst sectors and stakeholders, frustrating a participatory approach in planning and implementation. In developing its National Biodiversity Strategy, Argentina aims at a consensus building approach to involve the public in designing a national action framework. At first, the role of education and communication in this preparatory phase was not appreciated but soon became apparent that it was of primary importance. In the first phase of consultations the difficulties encountered were a lack of information on Argentina’s commitments to biodiversity conservation; how to involve some key sectors in the process, and a lack of interest from the media. The strategy for communication and education at this initiation phases is promoting the National Biodiversity Strategy and building capacity of key groups to effectively become involved and implement the action plan. Target groups for this capacity building and training include administrators, professionals, technicians, local community members, businessmen. The training is oriented to improve skills & knowledge in regard to biodiversity administration, control, management, & conservation. The strategy is to: • incorporate biodiversity issues into permanent training & capacity building programs for public agents and introduce special mandatory courses for officials, forming alliances with universities and institutions. 8 Public Education and Awareness • GBF Workshop Report Promote and develop training programs for project elaboration, management and financial operations. It has been recommended to reinforce and increase international exchange mechanisms. In Norway, a level of competence was assumed in other Ministries in requiring them to prepare sectoral strategies according to an agreed format. The Ministry of Environment gave feedback over many years to encourage and foster the ideas and strategies. However, encouragement has to be sustained to see these strategies become action plans, funded and implemented. Making information available Increasingly, governments are turning to web pages as ways of making information available and as part of the Clearing House Mechanism under the Convention. The Ministry of Environment Norway supports GRID UNEP to provide state of the environment reporting in condensed and simplified ways enabling the user to delve deeper for more detail if wanted. Information is presented in graphs and maps where possible to make the information more succinct. The Norway model for state of the environment reporting is being used by other countries, which will make comparisons possible. The web site also has applications to formal education and guidance on how to use it is provided to schools. As a policy instrument Many policy measures under the Convention are designed to influence or change behaviour of citizens and firms in such a way that they start doing 1 something new or stop doing something. Communication by itself may not be a sufficiently strong instrument to bring about change in behaviour. When used together with another policy instrument such as a subsidy, tax credit or a facility it can have the desired effect. In addition to supporting and strengthening other policy instruments, communication may also be used to: generate public debate on a particular topic, raise awareness of backgrounds and causes, increase involvement, ensure policy plans have a greater chance of being accepted and influence attitudes and behaviour. In Australia, the Coast Care Program funds community facilitators and projects to engage communities in playing an active role in restoring or conserving the coastal environment. Financial resources are an important part of triggering action. The Ministry of Environment Norway has provided financial as well as technical information on environmental education action plan that has developed a new core curriculum from the age of 6 up to university. This was achieved through co-operation with Ministries involved in education and environment. Educational programs are linked to the Ministries’ monitoring of biodiversity, so that the students’ work feeds into municipal and statewide information on biodiversity. 1 Communication tools include instruction, education, information, public relations, and marketing and advertising. 9 Public Education and Awareness GBF Workshop Report 10 Public Education and Awareness GBF Workshop Report Communication in the policy-making process. The underlying goal of communication as a factor in the policy making process is to act as a catalyst in improving relations between the government and the public. The normal practice has been for policy and policy measures to be cooked up in the ivory towers of civil servants. There may be even a perception that there has been involvement of “stakeholders” in the process. Frequently, these are an elite group that does not adequately reflect the reality. In South Africa, even at the protected area level, elite groups tended to dominate participatory processes and used these positions to try to provide benefits to their own group. Problems associated with community development -South Africa •The process of participation tends to only represent the socio-economic & environmental elite; •Community participation regarded as unnecessary, unwieldy, time consuming & idealistic dream; •Burdens - dilution of power, lack of time to interact, lack of patience to educate others & lack of negotiating skills; •Lack of money, co-operation, attendance & interest; •Extensive bureaucratic control •Lack of knowledge by the community •Lack of will power & initiative in the community Figure 8: Issues associated with participation and community development in South Africa. Solly Mosidi In some cases, policy making is followed up with consultation, with participation of those groups of people who are to be affected by the policy in question. In Norway, the government is responsible for making information available to the public, having open communication and participation in decision making. The national biodiversity strategy was agreed to by 7 Ministries with each sector being responsible for defining its own strategy. Public consultation was a part of each sectoral action plan. At the request of the Ministry of Environment municipalities are also drawing up plans for contributing to conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity thereby, involving communities in more local planning initiatives. To stimulate this input, the Ministry funded 435 environment officers in municipalities; however, now most municipalities continue funding them. When governments devise policies and measures in order to bring about changes that they deem desirable they often have trouble gaining public 11 Public Education and Awareness GBF Workshop Report acceptance. In other words, the public does not want to do what the government wants it to do. The workshop heard about the difficulties of the Netherlands government in implementing its Nature Policy Plan, necessitating a review of their process as described under. In the Netherlands, the government is increasingly aware that it is not possible for them to bear the responsibility for certain changes, but also that they should not aspire to do so either. For this reason there is a tendency for civil servants to abandon their ivory towers and seek to make policy in conjunction with relevant groups. This is not simply because such groups can play a role in implementing the policy in question but also because their experience and knowledge of what is feasible in practice, can make a valuable contribution to moulding the substance of the policy. Bringing together politicians, policy makers and general public to provide an answer to the question of how to involve the public in policy formulation is a task for which a communication expert is eminently suited. Moreover, communication is the oil in the wheels of this type of co-productive process. In the Netherlands, the Nature Policy aimed to create new nature – bogs, and forests, and to link existing natural areas with corridors. In the de Peelvenen region of the Netherlands, the government reviewed progress on its policy implementation. To achieve its policy, the government wants to buy land to create new natural areas. However, Dutch farmers do not see the government’s nature policy plan in the same way as the government. Therefore, trying to implement these policies and realising these goals is a problem of the government and it is not seen as the farmers’ problem. This creates a gap between the general interest and the individual - private interest. Dutch farmers’ perceptions of nature •Historical view: nature as an enemy •Farmers’ nature •Integration of nature in farm- management •No acceptance for strict nature •Nature as a license to operate Figure 9: Communication depends on understanding the perceptions of the other party. Farmers and the government both talk about “nature” but have different perceptions of what it means. Here Farmers’ perceptions are listed. Jan van Rijen Farmers’ lack trust in the authorities and see them as affecting their economic well being. Farmers also have a different perception of nature than conservation groups. Farmers were not happy about any wild areas of nature being re-created, as they had worked hard to change wild land to farming land over the past generations! Environmental NGOs were 12 Public Education and Awareness GBF Workshop Report confrontational, objecting to developments on farms, and advocating for wildness. The farmers saw NGOs as enemies. An interactive process was begun to build up trust between the players. The provincial government staff had to come out from behind their desks into the community, to become one of the community and to organise and facilitate the process to build relationships and networks. In the De Peel region a stalemate between the stakeholders existed. The way out of this situation was to turn inaction itself into a common enemy and work to overcome that. In building relations out of confrontation, small steps are taken, with the group designing a small project together as a way of building trust. U s in g fa rm e rs ’ p e rc e p tio n s • I n v e s t in th e p r o c e s s : – T a k e in te r e s t g r o u p s s e r io u s ly – u se a co m m o n en em y – s tim u la te in itia tiv e s ; b e p r o a c tiv e a n d c r e a tiv e s o th r e a ts can becom e chances – p a r tic ip a te in th is p r o c e s s ; b e v u ln e r a b le y o u rs e lf • O r g a n is e th e p r o c e s s – r e g io n a l c o m m itte e – in te g r a te d p la n s Figure 10: Summary of the steps taken by the Dutch government to work with Farmers In this new way of working, the government has to clarify its role in the process as the intent of its communication depends on how much the government is trying to influence the group. Communication can be used to generate support and commitment if the government is acting as a stage manager of the process. Or it can create new information via a process of interaction in negotiation. When the government plays simply the role of mediator it facilitates the process towards solving problems which become the responsibility of the organisations involved. Here the government plays the role of independent advisor and facilitates the smooth flow of information. One problem is that the interactive process takes time; a factor that is not popular with authorities from South Africa to the Netherlands. Once the communication process undertaken by government changes, government processes also have to change. For example, in the Netherlands, it is considered important to cut down on bureaucracy when becoming more sensitive to working with communities. In addition there needs to be an increase in financial incentives to support the agreed changes and the time of people to participate in the process. 13 Public Education and Awareness GBF Workshop Report Therefore, communication is one of the key critical factors determining the success of government policy and government itself. Without strategic communication management, both, government and management are deaf, blind and paralysed. Communication management can be effective only if it is a full and integral part of the policy process. That means that it is used as a tool for interactive policy making, and in all phases of the policy process. It is used in combination with other instruments and is adapted in process and vehicles to objectives, target groups and the substance of policy. If communication is to perform a key role for the government, the communicator must also occupy a key position in the government’s organisation. This, however, is an obstacle at present, even in advanced institutional and environmental nations like Norway. 14 Public Education and Awareness GBF Workshop Report The role of NGOs in Article 13 NGOs provide important agenda setting roles for society and government. In Nepal, the Nepal Forum of Environmental Journalists NEFEJ, established since 1986, has played an effective role in keeping issues before the government and the public. Seventy-five journalists in the country are members of the Forum, along with 25 experts as associate members. The Forum has built the capacity of journalists to investigate and report on environmental matters by giving fellowships to research and study issues, providing field visits and training programs, and giving an environmental journalism award. Journalist and decision-makers have interactive sessions. Radio and TV programs are produced as well as a wall newspaper for distribution in remote mountainous villages. The journalists mount advocacy on issues like pesticides, tourism, and urban development. Figure 11: Section of the large wall newspapers that are prepared by the Nepal Journalists Forum for distribution to villages. The text is written simply and those that cannot read seem to have the news read for them by those that can. Governments are increasingly inclined to join forces with NGOs and other intermediary organisations for communication purposes as NGOs may 1) foster public debate on an issue; 2) raise support amongst the target groups associated with them; 15 Public Education and Awareness 3) 4) 5) 6) GBF Workshop Report feed in information to the government about the public’s views; pass on messages, education or training; fill in gaps in terms of geographical reach; to be a more trusted agent of the message for some target groups. In the UK, British Trust for Volunteers has practical skills in mobilising community involvement in conservation and is used by the government to gain support for biodiversity conservation management practices in local government managed nature conservation areas. The NGO is able to provide training and most importantly back up services to maintain community interest and confidence. Mobilising community involvement to care for the marine and coastal environment is encouraged by an Australian government NGO sponsored program - the Marine and Coastal Community Network. Funds provide financing for community facilitators in each state and the provision of information and educational workshops aimed at presenting different views on issues. Members of the network are involved in defining a national ocean policy, carry out surveys on community attitudes to coastal development proposals, provide input to marine national parks and monitor marine species. An NGO, the Quebec Labrador Foundation works in collaboration with the Canadian Wildlife Service to address the problem of declining sea bird populations. To do so, the program has had to develop a sustained improvement in local knowledge, attitudes and behaviour towards sea birds as well as greater local participation in the management process. In the longest running and evaluated project, this example presents essential steps to planning education programs based on its 20 years experience. Above all, it proved the efficacy of education and the result has been an increase in sea bird populations. Often, the initiative to work with government comes from an NGO, as in many governments there are insufficient people to effectively organise a communication program. However, this approach can have its pitfalls. In Sri Lanka, with backing of the Ministry of the Environment, an NGO March for Conservation, based on university staff, trained hundreds of officers of state agencies in a comprehensive series of workshops on biodiversity conservation. Despite the apparent government support and engagement of its personnel in extensive training (even Directors, and Secretaries of Ministers were trained), the trainees were not subsequently involved in biodiversity policy or preparation of the action plan. This suggests that it is preferable, at the start, to institutionalise the training efforts for certification and evaluation professionally. It also indicates that NGO actions on nonformal education cannot be carried out in a vacuum if they are to have an impact on the course of action. In the Peruvian rainforest, concurrence between the Ministry of Education and Teachers Colleges has been fundamental to an NGO education project. Massive immigration to urban areas has resulted in people living in shantytowns, suffering from high rates of unemployment and impacting 16 Public Education and Awareness GBF Workshop Report on the rainforest. To educate city populations, a model school based project in 4 cities has been developed to revise the substance and process of education in relation to the rainforests and sustainable development. Government engagement is essential to hopes of future up-scaling the demonstration project to other areas of the country and to other grades. Figure 12: An example of the model educational project material produced in Peru. Fiorella Ceruti Indigenous peoples Indigenous peoples, concerned about the destruction of the environment, are also becoming more active in sharing their knowledge for the education system. This has demanded a change for the (Canada) Dene people’s oral traditions to one of preparing resources in print so teachers have access to the material. Use, however, is by no means universally accepted in the Canadian schools of the Arctic region. One factor in the resistance to using traditional knowledge and its spiritualism is reconciling this “pagan” perception with that of Christian teaching. The Convention on Biological Diversity has helped indigenous people to gain some measure of support for their traditional knowledge. Yet, there are difficulties in Canada to develop sensitivity in the bureaucracy and in its ways of working. One such area of difference is reconciling the top down government approach with the traditional one of consensus building. Even in its goodwill to develop an Arctic Strategy the government risks not building on the capacity in the community. 17 Public Education and Awareness GBF Workshop Report Lessons learned from managing networks to mobilise communities Networking facilitates links between groups and individuals and encourages more informed and energetic groups. In Australia Diane Tarte told how 1. Communities have a great deal of interest & concern for marine issues and genuinely want to do something. People also acknowledge the need for networking and information. 2. There is little knowledge of marine conservation and concerns are localised. 3. Despite limited knowledge, there are issues, icons, and habitats that attract the public’s attention. 4. People are confused about who is responsible for marine issues. 5. People are only just starting to communicate across State boundaries. Many issues are national, such as ballast water and the impacts of fishing and shipping. However there are few national efforts to address problems. Some of the lessons on networking presented in the workshop include: • • • • • • • Identify the issue(s) carefully so that the network can address them. Avoid extremely controversial issues otherwise the network becomes polarised. The strength and dynamism of a network comes from grass roots participation. Emphasis must be placed on cross linkages between participants, rather than establishing a top-heavy hierarchy of responsibility. Take time to establish trust so that co-ordinators, groups and individuals can begin working together. Be relevant- people need to see tangible result from the effort. Have continuity, a co-ordinator or facilitator can provide continuity and therefore resources for this are essential. Build laterally, rather than vertically. Networking facilitates links between groups and individuals and encourages more informed and energetic groups. Key tools to mobilise a community network for action are: • Regional Co-ordinators • Quarterly national and regional newsletters • Workshops and Government policy & planning fora • Regional visits and workshops by Co-ordinators • Free call national number • Radio programs • Web page • National awareness programs • Link to international special days • Gauging community opinion 18 Public Education and Awareness GBF Workshop Report International co-operation and Article 13 Article 13 calls on states to co-operate to develop educational and public awareness programs. One example of co-operation was Norway’s sponsorship of the Global Biodiversity Forum workshop enabling different people from all over the world to share their experience and to set the stage for providing guidance to the Parties. The workshop also heard about co-operation between Pacific Island governments on campaigns in the Pacific on turtle conservation and coral reefs. These were triggered with the assistance of the South Pacific Regional Environment Program, SPREP. In SPREP, campaign planning commenced one year in advance with fund raising, planning and support from heads of government. One advantage was the existence of a regional program and strong regional networks of organisations that could be the basis of the campaign action. Ten months before the campaign was launched, preparations began. A regional meeting decided on the campaign goal, target audiences, slogan and key messages and the support required at the regional level. Following the regional meeting, national campaign planning meetings were put in place in each participating country. Multi-sector groups were engaged in the planning at the national level such as religious groups, women, fisheries, education; and they were involved along with environment government departments and NGOs. At the regional level, support was given to national campaign actions; information was shared about what was happening in different countries; access to resources provided, and agreed common resources produced, such as posters and videos for use throughout the region. After the campaign a regional evaluation meeting was held. There was a high degree of ownership and involvement by countries with NGOs and governments working in a fun way together. The mass media were used to good effect to gain high exposure of the issues. The work was not without its difficulties, not least that of communicating in a region one sixth the area of the earth and lacking in many instances electronic means of communication. National resources, human and financial, were limited resulting in actions that were highly focused, though not as extensive as desired. Monitoring the impact is difficult, e.g. there are no media monitoring services. The international co-operation on the campaign • led to shared benefits from attracting sponsors, high exposure, shared music/songs, and shared ideas; • by using a participatory approach, ownership amongst countries is assured; • and high level endorsement of the campaign helped to facilitate implementation; Key characteristics of the campaign were 19 Public Education and Awareness GBF Workshop Report 1) region-wide heads of government endorsed the campaigns giving the highest political support possible; 2) the campaign approach was part of an agreed regional strategy; 3) a fully participatory approach to designing the campaign, implementing and evaluating it was undertaken; 4) co-operation between states occurred; 5) a network of national campaigns supported by SPREP at the regional level; 6) high degree of government, NGO and private sector involvement at the national and regional levels; 7) high degree of media coverage and involvement by educational institutions; 8) working links to wider international initiatives; 9) fun, empowering and innovative activities that reached targeted audiences. The key facts of the two campaigns, one on turtles and the other on coral reef are listed in the table from Sue Miller and Lucille Apis-Overhoff, SPREP. 1997 Pacific Year of the Coral Reef SPREP ( coordination role), participating Pacific Island countries, territories and NGOs Pacific Island region Location Region wide education and Type of awareness campaign project 2 years* includes campaign design, Duration implementation and evaluation To communicate the urgent need to Aim conserve coral reefs and related ecosystems in the region Campaign national and regional Campaign national and regional Target plans included a wide range of plans included a wide range of groups activities that were clearly targeted to activities that were clearly targeted key audiences e.g. government to key audiences e.g. government leaders, media, youth, community leaders, media, youth, community leaders leaders Cooperation • • National – through in-country National – through in-country governments /NGO campaign governments /NGO campaign committees committees • • Regional – through SPREP Regional – through SPREP coordination and coordination and governments/NGOs governments/NGOs • • International links to IUCN International links to ICRI and the Turtle network International Year of the Reef Multi donor including GEF, SPREP, Multi donor including GEF, SPREP, Financing member governments, private sector member governments, private and NGOs. sector and NGOs. New five year coral reef and Second Regional Marine Turtle Follow Up associated ecosystem strategic Conservation Programme Strategy action plan 1997-2001 * Note: campaigns were actions identified in existing and ongoing strategies and action plans Project Name of Organisation 1995 Year of the Sea Turtle SPREP ( coordination role), participating Pacific Island countries, territories and NGOs Pacific Island region Region wide education and awareness campaign 2 years* includes campaign design, implementation and evaluation To communicate the urgent need to conserve sea turtles 20 Public Education and Awareness GBF Workshop Report Lessons learned in managing an educational program Key points to consider in developing an educational plan were illustrated by Kathleen Blanchard from the QLF/ Atlantic Center for the Environment, USA who has conducted a long term educational project with a community to improve the conservation of sea birds. Based on this experience the following guidance has been prepared. Phase I Research and Goal Identification 1. Identify the need from the standpoint of biological diversity The need, often expressed as a traditional management goal, must be clearly stated and kept in focus, since the education program is an instrument to assist in the attainment of that goal. Examples: The restoration of depleted wildlife populations; the recovery of endangered, threatened, or rare species; the management of hunting to sustainable levels; the restoration of vital habitat. . Describe the need in tangible, manageable terms, rather than broad concepts or large geographic areas. Remember that what is about to be accomplished must be real and do-able to many people. Management approaches often are ecosystem based; but when it comes to practical application it is sometimes easier to understand a problem in terms of species, populations, or habitats. Projects should be organised such that all parties will understand what needs to be done and the specific things that they can do to help achieve success. 2. Identify stakeholders, inform them of the need. Involve stakeholders in the whole process from this point on. 3. Investigate the problem and its context thoroughly, from both biological and human perspectives. This will help to identify such aspects as: • root causes of the problem • knowledge of the problem among the stakeholders • attitudes specific to relevant behaviour and consonant with changes needed • motivating influences, both extrinsic ( eg regulations and fines) and intrinsic (norms, personal ethics, traditions) • barriers ( eg economic political, geographic,, cultural, legal etc.) to improvements • parties involved both in creating the situation and able to work towards solutions • decision makers and opinion makers The research should yield answers to questions relevant to establishing the necessary groundwork for a sound education program. Such questions might be: 21 Public Education and Awareness • • • • • • GBF Workshop Report How vital are the activities to the region’s culture Are the technologies appropriate to the need and to the resources? How have the activities changed over time? What is the prevailing opinion of management agencies, non governmental organisations, and outsiders in general? Is the region undergoing rapid development? What do people value? Education as a Conservation Instrument Planning evaluation outcome Research information stakeholders RESULTS STRATEGY EVALUATION Implementation timing & place KASA GOAL REPORTS 4. Modification of the goal Take the results of the research to the stakeholders and modify, if necessary, the management goal such that all parties can agree. Example, “the recovery of endangered populations of a species while preserving the integrity of the local culture”, or the “ protection of critical wildlife habitat while enhancing the economic development of the region”, or “ the protection of species while ensuring the basic life support needs (named) of the people.” The important point is to include a human component to the basic goal of biodiversity and to ensure that all parties agree to this goal. If there is conflict in achieving the agreed upon goal, then take time for all parties to elaborate. Try visioning or conflict resolution procedures and broaden the goal to basic fundamental principles. The principles of sustainability defined in “Caring for the Earth” are useful as fundamental goals on which most parties can agree. Language that expresses concern for future generations often works. 22 Public Education and Awareness GBF Workshop Report Achieving a goal on which all parties can agree is fundamental to the long term success of the project. It is the foundation for later effort. It is the basis for the establishment of trust. It is referred to constantly during the process and it ids the benchmark for the evaluation of the project and the success of the education intervention. If this step is missing or weakened then the project as a whole may fail in the long run. 5. Define the overall approach to achieving the goal and the role that education will take in an integrated plan that includes other instruments. What instruments will be used (e.g. education, legal, research, economic)? How will they relate to one another? What cross communication will be established so that each does not work in isolation from the other, but rather works in an integrated manner towards the attainment of the goal? Phase II Planning Formulate results of the education and target audiences such that they support the overall biodiversity goal stated in phase 1 The education results (objectives / goals) may be in terms of knowledge (cognitive), attitudes (affective), or in the practices (behavioural) or a combination of all three. Prioritise the educational goals, each with target audience, according to such factors as the management goal, ecological parameters, socio-economic factors and limits imposed by time and budget. Examples might be “ to increase public awareness of wildlife regulations”, or to increase knowledge amongst government agency personnel about the economic imperatives of the local culture.” 1. Establish educational objectives and learning outcomes. This will require use of information gathered during the research phase. An example might be, to “ increase willingness of fishermen to report their by catch.” 2. Devise a specified method or methods of evaluation to monitor performance of the plan in relation to the intended results. Establishing an evaluation plan must come early in the process rather than after activities are underway. As with all steps involvement and participation of people to be affected by the program helps to establish trust among all parties. 3. Develop the actual educational strategy The value of local participation is especially apparent at this point because successful strategies must subtly reflect local channels and styles of communication, ethical norms, and conditions. Choosing strategies 23 Public Education and Awareness GBF Workshop Report requires clarity about desired learning outcomes ( eg short term or long term ?) knowledge of available resources and considerable sensitivity to local leadership patterns and the ways the target group normally receives information. Too often strategies selected are merely those customary or familiar to the planner, for example, an educational brochure to provide information. Review the specifics of the situation and consider how much and what kind of information is actually needed by the target audience and who will deliver it. Some educational programs require long term delivery of services, a consideration that may dictate inclusion of strategies such as technical training, leadership development, and nurturing other sources of financial and technical support. For instance, the financial or other backing of corporations or industry may be essential if long term goals are to met; ongoing involvement of local organisations may be essential. Phase III - Implementation 1. Continue to build trust with the people involved and establish accountability so that they will be open to new information. 2. Understand the existing conceptual and behavioural constructs of the target audiences so that the introduction of new information, skills, and activities can link logically with the old. Not being alert to the learner’s perceptions or way of seeing the situation – can lead to misconceptions, cognitive dissonance and failure to hold people’s attention. This can be especially true for internal education programs designed for management agency personnel who are unaccustomed to dealing with the public. 3 Take advantage of well used channels of communication and adapt to the use of special events that may provide unexpected learning opportunities. 4. Go to where the people are and repeat the message in a wide variety of circumstances. Make repeated face to face contact with audiences. 5 Use innovative approaches to education Incorporate hands on activities. Include activities that develop knowledge, attitudes and skills and conservation behaviours. 5. Train local citizens and empower them for leadership roles in the project. 6. Use appropriate mass media such as community radio, cable TV, electronic mail etc. 7. Select field personnel who are able to relate well to people especially in cross cultural experiences. 8. Keep program mandates reasonable in scope and time frame so as to avoid burn out amongst workers or lack of financial resources just as 24 Public Education and Awareness GBF Workshop Report the project gains momentum 9. Emphasise the positive ( what has been accomplished) rather than despair over what needs to be done. Inspire and motivate, this can be just as or more important that providing information. Phase IV - Evaluation The purpose of evaluation is to measure the degree to which the educational objectives are being achieved and whether the education program is integrated with the overall management goals. It suggests how the program might be modified, such as by targeting new audiences, changing particular strategies, conducting more research, or enlarging the educational objectives. 25 Public Education and Awareness GBF Workshop Report Conclusions of the GBF workshop Education and communication are essential to achieve the objectives of the Convention on Biological Diversity, providing the means to connect people to biodiversity. Only then can responsibility for biodiversity be engaged. Results from educational programs can be as concrete as an increase in different species of seabird populations. But this is not education modelled on the idea that people are empty vessels into which we need to pour ever more information to effect change. It is education and communication based on building relationships and shared understandings. It is a process that engages people to participate in solving problems. The presentations at the workshop led to a high degree of accord amongst the lessons learned. The participants felt this could be presented as a set of guiding principles to the Parties including: 1. defining a shared goal among stakeholders; 2. incorporating local knowledge and culture; 3. involving stakeholders to plan, implement and evaluate policy and programs; 4. facilitating networks at all levels. The perspectives that arose in the workshop are not those indicated by Article 13 of the Convention which sees public education and awareness as separate activities rather than as an integral component of making policies and implementing them. Education and communication are important policy tools, just as economic and legal instruments. Obligations The imperative obligation of the Parties to Article 13 is clear as the Convention directs that the Parties shall undertake public education and awareness. This obligation demands the Parties to take responsibility at the national level and allocate human and financial resources to this instrument. The workshop suggested measures to make this more accountable such as - reporting on work undertaken on Article 13 at each COP meeting; - tabling public education and awareness action plans in connection with biodiversity action plans; - and to report specifically on how Article 13 is being implemented as an integral instrument in each theme. Funding Parties are urged to allocate budgets to fully meet their obligations under Article 13 - to lever funds by making it a GEF program area; including developing capacity in biodiversity education and communication; seek support from the World Bank and other multi-lateral and bi-lateral funding agencies; and stimulate increased funding for biodiversity education in formal education systems. Capacity Building 26 Public Education and Awareness GBF Workshop Report Human capacity to mobilise communities and individuals is limited. Therefore, it is recommended that the Parties develop institutional capacity to manage biodiversity education and communication programs and facilitate training of practitioners. International co-operation Parties should develop, as part of their action plans, ways to co-operate regionally and in all other relevant Conventions to develop the most costeffective ways of working. The Parties should consider endorsing the UN-ECE Convention on “Access to Environmental Information and Public Participation in Environmental Decision Making” going before the Aarhus Environment for Europe Conference, June 1998. 17/09/98 updated 12/05/2000 27 Global Biodiversity Forum - 10th Session Workshop on Public Education and Awareness Article 13 How to put it into Practicce 1-2 May 1998 List of Participants (in alphabetical order) Ms Marta Andelman Conservation and Management Foundation Maipu 853, Piso 3 1006 Buenos Aires, Argentina tel: +54 1 311-2233 fax: +54 1 312-6878 e-mail: master@webar.com Mr Tibor Baranec The Slovak Agricultural University in Nitra Dept. of Botany Slovak Agricultural University Tr. A. Hlinku 2 949 76 Nitra, Slovakia tel: +421 87-601 ext. 450 fax: +421 87-411 451 Mr Aake Bjoerke Information Manager UNEP/GRID - Arendal P.O. Box 1602, Myrene 4801 Arendal, Norway tel: +47 370 35-650 fax: +47 370 35-050 e-mail: bjoerke@grida.no Ms Kathleen A. Blanchard Quebec-Labrador Foundation Atlantic Center for the Environment 55 South Main Street Ipswich, 01938 Massachusetts, USA tel: +1 978 356-0038 fax: +1 978 356-7322 e-mail: kblanchard@qlf.org Mr Jan Brindza The Slovak Agricultural University in Nitra Dept. of Genetics and Plant Breeding Slovak Agricultural University Tr. A. Hlinku 2 949 76 Nitra, Slovakia tel: +421 87-601 ext. 787 fax: +421 87-411 451 e-mail: brindza@sai.uniag.sk Ms Maria Cecilia Wey de Brito PROBIO/SP - State Programme for the Conservation of Biodiversity of the SMA Environment Bureau of Sao Paulo State Av. Prof. Frederico Herman Jr., 345 Predio 2, sala 201 A. de Pinheiros, Sao Paulo CEP 05489-900, Brazil tel: +55 11 3030-6625 fax: +55 11 3030-6203 e-mail: sma.mceciliab@cetesb.br Ms Dora A. Lange Canhos Base de Dados Tropical, Fundacao André Tosello Rua Latino Coelho 1301 13087-010 Campinas Sao Paulo, Brazil tel: +55 19 242-7022 fax: +55 19 242-7827 e-mail: dora@bdt.org.br Ms Fiorella Ceruti Oficial de Comunicaciones y EA WWF Peru Programme Office Avenida San Felipe 720 Jesús María Lima 11 Peru Tel: ++51 (1) 261-5300 Fax: ++51 (1) 463-4459 Email: fiorella@wwfperu.org.pe Ms Antonia Chilikova Youth Environmental Organisation Rodopi 114 Pozitano Str., fl. 3, ap. 20 1000 Sofia, Bulgaria tel: +359 2 21-7623 fax: +359 2 77-7628 e-mail: chilikov@nat.bg Ms Miroslava Cierna DAPHNE Centre for Applied Ecology Hanulova 5/d 84140 Bratislava, Slovakia tel: +421 7 6541-2133 fax: +421 7 6541-2162 e-mail: daphne@changenet.sk Mr Graham Donald Head of the Biodiversity Action Plan Secretariat Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions Room 904, Tollgate House Houston Street BS2 9DJ Bristol, UK tel: +44 117 987-8850 fax: +44 117 987-8182 e-mail: european.wildlife.doe@gtnet.gov.uk Ms Viera Ferakova Prirodovedecea Fakulta Faculty of Natural Sciences Department of Botany Comenius University Revova 39 811 02 Bratislava, Slovakia tel: +421 7 531-2127 Ms Wendy Goldstein IUCN Education and Communication Programme Rue Mauverney 28 1196 Gland, Switzerland tel: +41 22 999-0282 fax: +41 22 999-0025 e-mail: wjg@hq.iucn.org Ms Julie Harlan World Resources Institute 1709 New York Avenue, NW 20006 Washington D.C., USA tel: +1 202 662-2518 fax: +1 202 347-2796 e-mail: julieh@wri.org Ms Latipah Hendarti RMI the Indonesian Institute for Forest and Environment Jl. Sempur n° 64 16154 Bogor, Indonesia tel: +62 251 32-0647 fax: +62 251 32-0253 e-mail: rmi@bogor.wasantara.net.id Ms Vera Kappers PAN Netherlands Pontanusstr. 37A 1093 Amsterdam, the Netherlands tel/fax: +31 20 694-0412 Ms Elin Kelsey 222 Laine Street, Apt 3 Monterey, CA 93940 USA tel: +1 408 648-1039 e-mail: elin@iname.com Ms Tatiana Kluvankova Institute for Forecasting Slovak Academy of Sciences Sancova 56 81105 Bratislava, Slovakia tel: +421 7 39-5256 fax: +421 7 39-5029 e-mail: tatiana@progeko.savba.sk Ms Sukianto Lusli Jamblangraya I/17 11270 Jakarta, Indonesia tel: +62 21 631-38-29 e-mail: slusli@wwfnet.org Mr Chris Maas Geesteranus National Reference Centre for Nature Management P.O. Box 30 6700 AA Wageningen, The Netherlands tel: +31 317 47-4820/2 fax: +31 317 47-4909 e-mail: c.maas.gesteranus@ikcn.agro.nl Mr Barney Masuzumi Dene Cultural Institute 7 Otto Drive Yellowknife, NT, X1A 2T9 Canada tel: +1 867 669-0613 fax: +1 867 669-0813 e-mail: bmas@internorth.com Ms Elaine McNeil SIAST International Services, 2505 23rd Ave. P.O. Box 556, Regina Saskatchewan, Canada S4P 3A3 tel: +1 306 787-1374 fax: +1 306 787-4840 e-mail: mcneil@siast.sk.ca Ms Sue Miller South Pacific Regional Environment Programme (SPREP) P.O. Box 240 Apla, Samoa tel: +683 21-929 fax: +685 20-231 e-mail: sprep@samoa.net Mr Dennis Minty Softwaves Educational Software Inc. P.O. Box 2188, St-John’s Newfoundland, Canada tel: +1 709 722-6680 fax: +1 709 753-0708 e-mail: dminty@firstcity.net Dr Jonathan Mitchley Environment Department Wye College University of London Wye, Ashford, Kent TN25 5AH UK tel: +44 1233 81-2401 fax: +44 1223 81-2855 e-mail: j.mitchley@wye.ac.uk Mr Rob Monro Zimbabwe Trust Box 4027 Harare, Zimbabwe tel: +263 4 72-2957 fax: +263 4 79-5150 e-mail: monro@zimtrust.samara.co.zw Mr Solly Mosidi Head, Environmental Education Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism Private Bag X447 0001 Pretoria, South Africa tel: +2712 310-3781 e-mail: opv_sm@ozone.pwv.gov.za Ms Sylvi Ofstad Royal Ministry of Environment Myntgaten 2 0030 Oslo, Norway tel: +47 22 24-5714 fax: +47 22 24-2772 e-mail: sylvi.ofstad@md.dep.no Dr Ronald Orenstein Humane Society of the United States 1825 Shady Creek Court Mississanga, Ontario, Canada tel: +1 905 820-2886 fax: +1 905 569-0116 e-mail: ornstn@inforamp.net Mr Hans Olav Otterlei Managing Director Burson-Marsteller 24-28 Bloomsbury Way LONDON WC1A 2PX Tel: ++44-171 300 6442 Fax: ++44-171 831 6638 email: hans_otterlei@bm.com Mr Juan Ovejero Africa Resources Trust Rue Jules Lejeune 32 1050 Brussels, Belgium tel/fax: +32 2 343-0604 e-mail: ovejeroart@compuserve.com Dr Nirmalie Pallewatta Senior Lecturer Department of Zoology University of Colombo P.O. Box 1490 Colombo 3, Sri Lanka tel: ++941 580-246/594-490 fax: +941 59-4490 e-mail: nirmalie@eureka.lk Ms Daniela Panakova Slovak Republic email: panakova@fns.uniba.sk Ms Anita Prosser 36, St Marys Street Wallingford Oxfordshire OX10 0EU, UK tel: +44 1491 83-9766 fax: +44 1491 83-9646 e-mail: A.Prosser@dial.pipex.com Ing Jan van Rijen Ministry of Agriculture, Nature Management and Fisheries Postbus 6111 5600 HC Eindhoven The Netherlands tel: +31 40 232-9181 fax: 31 40 232-9199 Email: j.p.m.van.rijen@lnvz.agro.nl Mr Jan Seffer DAPHNE Centre for Applied Ecology Hanulova 5/d 84140 Bratislava, Slovakia tel: +421 7 6541-2133 fax: +421 7 6541-2162 e-mail: daphne@changenet.sk Mr Mangal Man Shakya Nepal Forum of Environmental Journalists PO Box 5143 Thapathali, Kathmandu, Nepal tel: +977 01 26-1991/26-0248 fax: +977 01 26-1191 e-mail: nefej@env.mos.com.np Andra Suchankova Cervenakova 5 841 01 Bratislava Slovak republic fax: + 421 7 374 266 tel.: + 421 7 764 207 email: suchanek@isnet.sk Ms Diane Tarte IUCN Regional Councillor Executive Officer Australian Marine Conservation Society P.O. Box 3139 (Level 1, 92 Hyde Road) Yeronga, 4104 Queensland, Australia tel: +61 7 3848-5235 fax: +61 7 3892-5814 e-mail: dtarte@ozemail.com.au Ms Elena Vartikova GREENWAY P.O. Box 163 81499 Bratislava, Slovakia tel/fax: +321 7 541-4674 e-mail: vartikova@ba.telecom.sk Ms Julia Ruth Willison Botanic Gardens Conservation International Descanso House, 199 Kew Road Richmond, Surrey TW9 3BW, UK tel: +44 181 332-5953 fax: +44 181 332-5956 e-mail: jw%bgci@rbgkew.org.uk Ms Jana Zacharova Ministry of the Environment Nam Stura 1 812 3T Bratislava Slovak Republic tel: ++4217 516-2211/516-2031 e-mail: zacravova@hotmail.com 5/26/00

© Copyright 2025