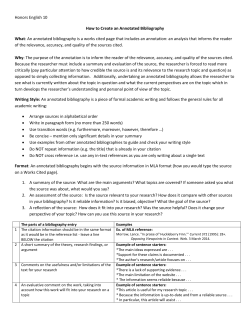

www.alastore.ala.org