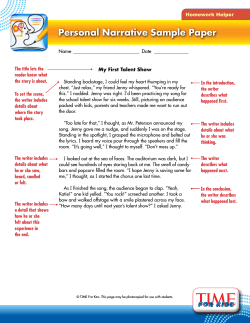

How to Write a Winning ... By Jon M. Shane November 12, 2002

How to Write a Winning Grant Proposal By Jon M. Shane November 12, 2002 Copyright www.jonmshaneassociates.com Copyright www.jonmshaneassociates.com Introduction At a time when most law enforcement agencies are being asked by their communities, through their elected officials, to do more with less, using grants funds to supplement the Department’s budget is a perfect method toward achieving the agency’s goals. Policing is an expensive endeavor, sometimes as much as twenty to thirty per cent of the city’s entire budget; often ninety to ninety-seven percent of the police Department’s budget is dedicated to salaries and benefits. That leaves very few dollars for equipment or overtime to embark upon new initiatives. Grant programs provide a source of relief for fiscally strapped cities and towns. Whether the agency is large or small everyone can benefit from using grants. During the 1970's the Law Enforcement Assistance Administration (LEAA) began establishing grant programs. The LEAA program was designed to improve an agency’s infrastructure and to bring about change within the agency. Purchasing equipment, sharing technology, hiring personnel and increased training were the themes. Although much has changed since the 1970's, much has not. These very themes continue to dominate most program strategies. Improvement and change are the key considerations of most grants. Whether a Department’s current methods and operations need improvement or an agency’s practices need to change to conform to contemporary standards, grants serve to bridge the gap between imagination and practice. Receiving grant funds can be very advantageous. A combination of hiring initiatives and equipment purchases will improve service delivery while bolstering a Department’s image and reputation. Remember that the public is the indirect recipient of the grant award. One’s grantsmanship can have a profound effect on crime, the fear of crime, corrections, alternatives to Copyright www.jonmshaneassociates.com -1- incarceration, juvenile delinquency, and the overall quality of life for every citizen the Department serves. However, there are disadvantages to applying for funding. The process can be labor intensive: researching, designing charts, obtaining letters of support, gathering endorsements and forming partnerships. Then, should funding be awarded, there are special conditions set by the funding source that the Department must abide by. Finally there is monitoring and tracking: did the Department meet its intended goals? Did the Department accidentally supplant1? Is the Department at risk for an audit? There are a myriad of different forms and reports required by the funding agency usually on a monthly, quarterly and annual basis. Of course these reports are due amid the regular daily work! All too frequently criminal justice agencies find themselves separated from the grant process because of inexperience. “Where do we find the funds?” “How do we apply?” “What’s expected of the agency?” These questions are heard from every agency executive that ever sought after grant funds the first few times. The assumption is that when the Chief says to the Deputy Chief “I want you to apply for this grant. Just write it up, get it done,” miraculously the funding source will select your proposal over the 2,000 other proposals they received. Not so. Grants are both competitive and often discretionary. To the uninitiated writing competitive discretionary grants is intimidating. The entire research and writing process takes a creative genius, which may not result in an award. This article is designed to bring even the most inexperienced grant writers into the competitive arena. Experienced grant writers may find this article refreshing with a different perspective. If an agency adopts the principles outlined here, the prospects for success will Copyright www.jonmshaneassociates.com -2- improve greatly. The entire grant application process is provided here and will furnish readers with an understanding of not only where to seek funding but how to write a winning proposal. Funding Sources A variety of funding sources exist from federal and state agencies to private corporations. The most overlooked source is the private sector. Many companies have a philanthropic extension willing to fund projects and programs that represent their company’s interest.2 These are some potential sources: Federal Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA) 1-800-421-6770 http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/BJA/ National Institute of Justice (NIJ) 1-800-851-3420 http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/nij/ Office for Victims of Crime (OVC) 1-800-627-6872 http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/ovc/ The Office of Community Oriented Policing Services (COPS Office) 1-800-421-6770 or 202 616-3031 http://www.usdoj.gov/cops/home.htm Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP) 202-307-5911 http://www.ojjdp.ncjrs.org/ National Institute of Corrections (NIC) 1-800 995-6423 http://www.nicic.org/ Copyright www.jonmshaneassociates.com State Private Contact the State’s “administrative agency” for assistance. For example, in New Jersey the administrative agency is the State Division of Criminal Justice; in California it is the Office of Criminal Justice Planning. The State’s administrative agency is responsible for passing through federal funds to local jurisdictions. Often the federal government does not make funds directly available to the local jurisdiction; the federal government passes the money to the administrative agency who then disseminates it to the local jurisdictions. A significant source of funding for programs on a state level is the Edward Byrne Memorial State and Local Law Enforcement Assistance Formula Grant Program (Byrne Formula Grant). Contact the administrative agency and ask for a copy of this program. There are literally thousands of private foundations that fund hundreds of program areas each year. Besides the internet or the library as a research mechanism, the following company publishes resource guides to assist you in targeting only those foundations awarding programs in your geographical area: -3- Research Grant Guides PO Box 1214 Loxahatchee, Fl 33470 561-795-6129 561-795-7794 (Fax) These guides are extremely useful. First, they are categorized so you only need to review the guide for the category for which you are interested (i.e., equipment grants, building grants, social service grant, etc.). Then they are arranged by state further organizing each guide into a comprehensible format. Another source is the National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS). The NCJRS is a federally sponsored information clearinghouse for people around the country and the world involved with research, policy, and practice related to criminal and juvenile justice and drug control. Check their web site for details on funding opportunities: http://ncjrs.org/. When contacting the funding source ask for an RFP (request for proposal). The RFP is the official announcement from the source that grant funds are available. The agency may have many RFP’s available, if so, specify which RFP’s are needed: your Department may be seeking funds to hire personnel, or purchase equipment, or fund a special initiative for a target population. If the funding source states that they do not have an RFP that fits the specific program being requested, then ask to have all of them sent to the Department. Oftentimes the person receiving the call is not sufficiently trained to interpret the request; often they do not have a criminal justice background and do not fully understand what is actually meant. Once the Department receives the RFP the individual programs can be digested and a determination can be made as to whether funding is applicable. Life of a Grant The life of a grant begins with the decision to apply for funding. Usually a member of the command-staff or the chief executive first creates the interest (e.g., the desire to form a new anticrime task force, or to enhance services for domestic violence victims, or to implement an overtime program for DWI). Once it is determined that the current operating budget is insufficient to harness the idea, the grant process begins. As indicated earlier, the funding process is labor intensive and can be intimidating. Depending on the jurisdiction’s form of government and the level of bureaucracy, the grantdevelopment team may be up against a very cumbersome application process, or one that flows Copyright www.jonmshaneassociates.com -4- rather easily. Here is an illustration of the individual steps that comprise a typical application process: Whatever the process do not be discouraged. The rewards, both personal and organizational, are tremendous. There is a great sense of accomplishment when the final draft is submitted and the award letter is received congratulating the Department. Typical Grant Application Process S tep 1 S te p 2 S tep 3 RFP/Solicitation is reviewed for eligibility and program No requirements Project is abandoned Project is abandoned S tep 4 S tep 5 Application and Resolution are reviewed, approved and signedNo by Chief Executive S tep 6 Project is reviewed; discussion is opened Project is abandoned No Police Department conducts a needs assessment Grant application is drafted and reviewed by Command Staff personnel Request RFP/Solicitation from funding source Grant application is sent to Legal Affairs. Resolution to Participate is prepared Resolution is delivered to the following for endorsement and approval: S tep 7 Application is rejected by funding source No No Resolution & application are presented to City Council for vote Application is sent to funding source for review Sources Signatures Required · Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA) · Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) · Office of Community Oriented Policing Services Corrections, additions and (COPS Office) deletions are made · Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP) · National Institute of Justice (NIJ) ·Office for Victims of Crime (OVC) · State Adminsitrative Agency Staff meeting held to determine applicability Grant project is awarded; award letter and supporting grant documents are sent Resolution to Accept is prepared by Legal Affairs Copies of award letter, application and signed contracts are sent to budget office for budget insertion Signatures Required · Contracts/Special Conditions are signed by Mayor S tep 8 Budget insertion and sent to next council meeting for approval Budget office assigns budget codes; lineitem is established Project is abandoned Budget office notifies the Police Department that the budget is on the system; spending may begin Police Department begins to spend funds Municipal Council accepts/rejects the Resolution S te p 10 S te p 1 1 · Identify Vendors · Hire Personnel · Purchase Equipment · Other uses Budget codes enable the spending process S t ep 12 S te p 1 3 Police Department tracks spending Fiscal Responsibility Council Vote · Chief Executive · Corporation Counsel · Business Administrator · City Clerk · Council Sponsor S te p 9 · Corporation Counsel · Business Administrator No · City Clerk · Council Sponsor · Progress reports prepared · Financial statements prepared · Reimbursement vouchers prepared S t ep 14 S tep 15 The fifteen steps listed above represent approximately four to six months worth of effort. In most situations approximately thirty to fifty percent of the time is spent waiting for the funding source to review the proposal. Remember, if the funding agency is a government entity, then they are receiving hundreds, possibly thousands, of applications from Departments around the country. Copyright www.jonmshaneassociates.com -5- Each proposal must be accounted for, assigned to a reviewer, and reviewed (accepted or rejected for funding), until finally the award announcement is made. Gathering Materials Before the writing process begins it is necessary to gather sources of information and conduct a literature review on the topic. An excellent starting place is the grant writer’s own knowledge and experience. Life experience (particularly within one’s profession) is a rich place from which to draw information; the various assignments that one may have been held throughout their career, a person’s educational pursuits or possibly a different job at some point in the writer’s life all contribute to a personal library of information. A natural corollary that flows from using personal experiences is using the experiences of others. Consider conducting an interview. First, define the purpose of the interview. After preliminarily researching the topic decide whom to interview. It is best to go to the top, executives, administrators, division heads, section chiefs and directors. They are likely to have a broad understanding of the policies, issues and procedures on the topic in question. Often they can provide the writer with specific information that is necessary regarding the proposal, and if not, they can at least identify the right person. Probably the most convenient and extensive way to gather materials is through the internet. Using meta search engines3 further reduces the amount of time spent searching for results. The local library’s reference section is yet another place to assemble materials. And every accredited college or university has a web site, the NCJRS and the National Council on Crime and Delinquency (NCCD) collection are some of the thousands of places to begin researching the proposal. Copyright www.jonmshaneassociates.com -6- There are also research groups dedicated to improving policing. Two of the most prominent “think tanks” are The Police Foundation and the Police Executive Research Forum (PERF).4 Both organizations have conducted some of the most historic and notable research on policing ever written. Their studies include the Newark Foot Patrol Experiment, the Kansas City Preventive Patrol Experiment, Racially Biased Policing: A Principled Response and The Police Response to Gangs: Case Studies of Five Cities. These two organizations have both free and premium publications which may prove indispensable to the proposal’s development. Supporting Your Ideas After the resource materials have been gathered and the writing process begins it is necessary to support the ideas. Support for the program can come from a variety origins such as authorities (also known as subject matter experts), examples, or statistical illustrations. For virtually every program a Department can conceive there will be an authoritative documented source available which will support the concept. If the program being designed is a patrol augmentation program locate authors Charles D. Hale or Tony Pate; a community policing program try authors Robert Trojanowicz, James Q. Wilson and George L. Kelling; a problem solving or situational crime prevention program try Ronald V. Clarke, Marcus Felson or Herman Goldstein; a juvenile justice program try authors John T. Whitehead and Steven P. Lab; a supervision program try Nathan F. Iannone. These are some of the most influential academics and practitioners who have used scientific methods to lend credibility to the social sciences, particularly policing. Authoritative support is when a respected author or publication is cited on the topic under consideration. This demonstrates that the Department is not just espousing a theory or advancing a supposition, but that the topic actually has been studied scientifically or the theory has been proven. Most people are influenced by the testimony of other people when dealing with topics Copyright www.jonmshaneassociates.com -7- they are unfamiliar with. By quoting or paraphrasing authorities, the reader (i.e., the review team) will tend to respect their statements because of their special knowledge or experience on the topic in question. “Research has shown that vivid, concrete examples have more impact on [readers’] beliefs and actions than any other kind of supporting material.”5 With examples ideas become specific, personal and lively. The Bible is an extraordinary source of examples where stories, parables and anecdotes make abstract principles clear and compelling. There are two types of examples that can be used, factual and hypothetical. A factual example is a story of a true incident as it relates to the proposal. A hypothetical example is an imaginary situation (often fiction based on fact) that relates to the general principle of the proposal. When using hypothetical examples a realistic scenario is created. It is then related directly to the proposal and captivates the reader (again the review team). Then, if real statistics are incorporated, it gives the perception that this undoubtedly could happen in real life! Indeed it is recommended that the writer use statistics to support the hypothetical example so it does not seem too far-fetched. Finally, this is an age of statistics. Expressing what is actually meant numerically often gives others a sense of security in their own knowledge. It also affords the reader the opportunity to visualize the intensity of what is being said, or to feel the impact of a particular problem. There is a widely shared belief that, when used properly, statistics offer an effective way to clarify and support ideas. To avoid falling victim to unreliable statistics ask the following questions: 1 - Are the statistics from a reliable source? 2 - Are the statistics representative? If the answer to either of these questions is “no,” then the writer risks misrepresenting what they are trying to portray. Therefore, statistics should be used to quantify ideas and give them numerical precision. Whenever possible visual aids should be used to clarify statistical trends. A Copyright www.jonmshaneassociates.com -8- simple pie chart, time line, or bar graph will show the relationship between a time period and the particular social condition. The two charts listed here are a 100% stacked bar chart and a time series chart. Source: 2002 Anytown Police Union Source: U.S Census Bureau 1930-1995 Ethics The goal of grant writing is to receive funding—but not at any cost. Writing is a form of power and therefore carries with it a heavy ethical burden. People will be influenced and persuaded by presentation. This is how your Department’s proposal will be funded over the others. The question of ethics in grant writing usually centers around the writer’s goals and methods. Make sure the goals are ethically correct. As a criminal justice professional and (probably) a government representative, if worthless or wasteful programs are lauded, the Department is on Copyright www.jonmshaneassociates.com -9- shaky ground ethically. Similar caution extends to the grant writer’s methods. Even if the goals are ethically correct, the grant writer is not being ethical if cheap and careless methods are used. Basically this signifies that the “ends do not justify the means.” There are five recognized considerations for ethical grant writing: Subject Awareness - The writer has an obligation to himself or herself, to the granting agency, and to the public being served. Understand the program for which the Department is applying and how it relates to the city, to the Department, or the Department’s mission or vision statement. Service is the credo, not selfservice. Honesty in What You Say - The writer must be cognizant of the temptation to distort facts and figures for their own purposes. Responsible writers do not falsify facts, present few facts as representative of the whole picture or use tentative findings as conclusive evidence. Employing Valid Reasoning - It should suffice to say that responsible writers take affirmative steps to avoid making hasty generalizations, asserting casual connections where none really exists, using invalid or absurd analogies/examples and yielding to prejudices Using Sound Evidence - A grant that is awarded is not full of “fluff.” It contains real circumstances that are supported by qualified, objective sources. This also means avoid plagiarizing. Plagiarizing - Generally, the grant proposal is a collaboration between the writer and his or her sources. To be fair and ethical, the writer must acknowledge the borrowing of another writer’s ideas and words by documenting the source. To borrow without proper documentation is a form of dishonesty known as plagiarism. Plagiarism occurs in two forms: 1) borrowing someone else’s ideas, information or language without documenting the source and 2) documenting the source but paraphrasing the source’s language too closely without using quotation marks to indicate that words and phrases have been borrowed.6 Most criminal justice professionals and many universities use the American Psychological Association (APA) style of citation when writing. Consult a good writing handbook such as The Chicago Manual of Style or The Bedford Handbook for Writers for documenting sources. Give credit where credit is due; if someone else’s material is used, cite it! Writing the Actual Grant Needless to say this is the test of the grant writer’s determination and creativity, which will coalesce into a comprehensible, meaningful and persuasive document that brings money into the agency. Remember that the grant writer is selling something: they are selling a concept, they are selling belief in the city/agency, they are convincing people to invest in the city/agency because a Copyright www.jonmshaneassociates.com -10- worthwhile service is being offered. Draft the grant proposal with these basic principles at the forefront: Presentation - Probably the single most salient feature of the grant package! Presentation is so important because there is no second chance to make a first impression. Use headers and footers in the document; make sure each page is numbered; use a good word processing program, never hand write the proposal; use good binding materials; use letterhead with original signatures, and do not fold or crease the paper; use color printing but do not leave the document gaudy with too many different colors; use charts and graphs to depict data; organize the document logically and according to the RFP requirements; include an eyecatching cover page that boldly identifies the name of the program and the agency; grammar check and spell check the document, and have it proofread by someone other than the writer, and above all else follow the instructions offered by the funding source. Language, Grammar and Punctuation - Words are the tools of a writer’s craft. Choose the right words for the job at hand. Do not use a word unless its meaning is clear, if unclear look it up; use a thesaurus, vary the words, but do not use big complicated ones. The exception to this is when there is a need to explain or clarify a difficult subject, such as DNA testing procedures, forensic science equipment, or computer equipment; avoid sexist language—do not refer to all members of an occupational group as “he.” Say he or she or change the pronoun to they; use the “eight parts of speech”: noun, pronoun, verb, adjective, adverb, preposition, conjunction and interjection—these are recognized as the traditional parts of English grammar; use all of the common punctuation marks: period, comma, exclamation point, question mark, semicolon and the colon. The substantive provisions of the grant are defined by the respective funding source. The provisions will vary among sources, but all grantors have basic requirements: problem statement, goals and objectives, program strategy, and budget narrative. Other substantive requirements that funding agencies may desire are: management structure, organizational capability, an abstract, curriculum vitae of participants, matching funds requirement (local match sources), projected milestones or accomplishments, geographic location, a statement of the project’s anticipated contribution to criminal justice policy and practice, continuation and retention, additional resource commitments and a statement of the program’s contribution to the State’s strategy (Byrne formula). Copyright www.jonmshaneassociates.com -11- The Process Organize the grant according to the following format. Many Departments seeking grant funds do not follow a predefined format and therefore their application does not have logical flow. By following these steps a grant writer will increase their prospect of an award: 1. Cover Page - Design a cover that is bold and attractive. Include: 1) the name of the grant, 2) a subtitle, if any, 3) the name of the grant program from which funding is being sought, 4) the funding agency, 5) the date of submission, 6) the city and state, and 7) the name of the agency. Use graphics and color to heighten the appearance. 2. Table of Contents - A table of contents should always be included so when a reviewteam member wants to refer back (or to refer someone else) to a specific provision they will know where to go without fumbling through each page. Use outline format and indent the subsections for clarity. 3. Abstract - If required, this is a one page description of what the program proposes to do and the expected results. It is a summary of the important points of the program; highlight the key aspects of the problem statement, the program description and the goals and objectives. 4. Problem Statement - This is the bedrock upon which all else rests. If there is no problem to overcome, then funding is not needed. Set a historical perspective that leads from the beginnings of the problem, through different time periods up the to the current condition. If it is a crime problem, insofar as possible, make a correlation between the crime problem an underlying criminological theory (i.e., rational choice, routine activities, social disorganization, conflict). Also, identify the antecedents that preexisted or coexist with the crime problem. Use statistics and a variety of charts to bolster your claim: extract percentages, use rates and add trend lines. 5. Goals and Objectives - Goals and objectives are often used interchangeably when, in fact, they are two distinct criteria that must be met. A goal is a broad general statement explaining what the grant program is expected to accomplish. Objectives are specific, precise and exact statements which lead step by step to the achievement of the goals. Goal statements often start with action verbs such as “To or Will. . .”. (e.g., To reduce inmate population; to reduce fear of crime; Will strengthen community partnerships; Will minimize the temptation to join a gang). There are four elements of an objective that must be met in order for them to be measurable: subject, assignment, condition, and standard. A. The subject represents who is tasked with doing something? (e.g., The Tactical Narcotics Team. . .; The Patrol Division. . .; The Municipal Court system. . .). The subject is the organizational element or person that will be responsible for accomplishing what your program is designed to do. Copyright www.jonmshaneassociates.com -12- B. C. D. The assignment represents what the subject is to do (e.g., To effect arrests for curfew violations. . .; To expedite incoming prisoners. . .; To conduct a workload analysis. . .). The assignment is an action. It explains the specific task (or responsibility) that is required of the subject in question. The condition represents the given circumstances under which the task must be performed. Conditions may be environmental or situational. (e.g., In the field. . .; At the domestic violence advocacy center. . .; In the county jail. . .). Conditions explain how, where, and with what the assignment is to be done.. Because the condition represents the “given” circumstances under which the assignment will be performed, in many cases the objective will contain the word “given” (e.g., Given a cellular telephone the neighborhood patrol officer will. . .). The standard specifies how well the task must be accomplished. The standard defines what the expected or anticipated results will be (e.g., Without error. . .; with 90% accuracy; According to approved agency policy and procedure. . .; Within the first month. . .). Here is an example of goals and objectives: Narcotics Enforcement Program Goal C To reduce narcotics complaints by 25% within the first six months. C To secure guilty pleas or convictions in 80% of all cases. Objective C To deploy the Tactical Narcotics Team, who will use covert surveillance techniques within the target area, for the first eight weeks. C To deploy the Special Investigation Unit, who will conduct undercover (UC) and confidential informant (CI) narcotics “buy” operations within the target area, for the first twelve weeks. C To deploy the Special Investigation Unit, who will apply for search warrants at locations within the target area in response to the UC and CI intelligence, throughout the duration of the program. C To employ the Emergency Response Team, who will execute all search and arrest warrants within the target area, throughout the duration of the program. C To assign a Special Narcotics Prosecutor, who will investigate and prosecute all individual cases as part of a RICO scheme when the case involves a firearm or the weight of the contraband seized equals or exceeds 1 U.S. pound, throughout the duration of the program. C To assign uniformed patrol officers, who will conduct situational crime prevention operations for those locations within the target area that are responsible for ten (10) or more calls for service, during the last fifteen weeks of the program. Copyright www.jonmshaneassociates.com -13- 6. Program Strategy - The program strategy is the specific method or activities that are to be employed for the duration of the grant program. In this section the requirement is to provide a clear statement of how the project is going to be organized and administered in order to meet the intended goals and objectives. The writer should meet with the various Departmental elements involved in carrying out the plan; identify what each organizational element is prepared to commit (e.g., fifteen police officers from the Tactical Narcotics Unit; one municipal prosecutor dedicated to the program; five street sweepers from Sanitation for neighborhood clean up; three drug and alcohol counselors from Health and Human Services, etc.). If the RFP requires, identify specific individuals who, by virtue of training and experience, will carry out portions of the program, and attach their resumes. In short, this section requires the writer to state the means which will be will be used to achieve the ends. 7. Budget Narrative - The budget narrative is a detailed, comprehensive itemization and explanation of the costs incurred from the administration and implementation of the program. Budgeted costs must be reasonable, allowable and cost effective for the activities proposed in the program strategy. The budget narrative must also describe and explain how each particular item was calculated. The typical budget categories that may be required are: personnel, fringe benefits, travel, equipment, supplies, contracts, utilities, construction, indirect costs and consultants. When creating the budget there is one issue that must not be overlooked: take extra care to ensure that the budget is in proportion to the goals and objectives. Often times the goals of the project far exceed the funds being requested, thus making the goals unattainable. This is known as the reasonableness requirement of the budget. 8. Appendix - Often times a grant application has a page restriction, limiting the narrative portion. If this is the case, include an appendix that contains all of the charts, tables and supporting documents. Do not waste valuable space in the actual narrative section, append all of your supporting materials, which can be located by an in-text citation (i.e., see chart 1 in appendix). All letters of support should be on company letterhead with original signatures, again, do not fold or crease the paper; create organizational charts, flow charts depicting a particular process, Gantt charts depicting a sequence of events and milestones, and include additional statistical data here too. A variety of off-the-shelf software applications exist for creating charts and flow diagrams, which are very user friendly. These programs can clearly illustrate complex processes and strategies, and can present ideas and information with greater impact through the power of clear visual communication. Copyright www.jonmshaneassociates.com -14- Summary Because of obvious space limitations it is not possible to cover all of the nuances that arise during the grant development process. However, the essential elements of researching, writing, and organizing a grant have been illustrated. The below listed cause and effect diagram summarizes the primary grant components and provides a graphic representation of the relationships necessary for a winning grant proposal. Table of Contents Clearly identify the pages and sections of the grant application Goals and Objectives Abstract Concise description of the problem, goals and what you propose to do Objectives : specific, measurable, step by step procedures leading to the goals Goals: broad statements about what you hope to accomplish Budget Narrative Correlated with goals and objectives Reasonable Winning Grant proposal Identify what needs to be improved or changed Bold, Eye Catching Cover Page Problem Statement The methods and design intended to be employed Authenticate the problem with statistics, empirical data, and authoritative sources Append charts, tables, letters of support and other supporting documents Organization and administration of the program Program Strategy Appendix Whenever a Department is tasked with addressing a problem consider the grant process as a viable solution. A Department can use grants to start new initiatives or supplement existing ones. Millions of federal, state and private funds are dispersed every year, but you have to be in it to win it! So the next time a staff member must draft a grant proposal apply the principles outlined here. By adhering to these basic concepts the writer will add strength and credibility to their application. And once the award letter comes congratulating the Department as being a winner, one can proudly proclaim that their efforts directly contributed to the image and reputation the Department enjoys with the community. Copyright www.jonmshaneassociates.com -15- Notes 1. Grant funds must always supplement the city’s budget, not supplant the previously authorized budget. Supplanting can occur in several ways. The most common form of supplanting is when the agency uses grant funds in place of previously appropriated funds. For example, the city has appropriated $3 million for vehicles. The Department then receives a grant for $3 million and purchases vehicles from grant funds and does not buy any vehicles from the previously budgeted funds. The Department has just supplanted the original funds with the grant funds. This is always impermissible and may result in the city having to return that portion of the funds which were supplanted. There are other more subtle ways in which supplanting can occur, if the city is not certain about whether they are supplanting, contact the funding agency and pose the scenario to them. 2. The difference between a project and a program is that a project is usually short in duration with a narrow purpose: to computerize the Department, to replace the Department’s fleet, etc. A program is a system of opportunities designed to meet a social need often long in duration: a quality of life program, an auto theft suppression program, etc. Private companies enjoy associating their name with projects and programs that reflect their business: insurance companies often donate vehicles, and computer companies donate hardware and software. 3. A meta search engine is an internet “search engine of search engines.” A meta search engine searches several other internet search engines at the same time for the information requested. This way you cover more territory with one request than having to go through each individual search engine. 4. “The Police Foundation is an independent and unique resource for policing. The Police Foundation acts as a catalyst for change and an advocate for new ideas, in restating and reminding ourselves about the fundamental purposes of policing, and in ensuring that an important link remains intact between the police and the public they serve.” The Police Foundation can be reached at www.policefoundation.org. “The Police Executive Research Forum (PERF) is a national membership organization of progressive police executives from the largest city, county and state law enforcement agencies. PERF is dedicated to improving policing and advancing professionalism through research and involvement in public policy debate. Incorporated in 1977, PERF's primary sources of operating revenues are government grants and contracts, and partnerships with private foundations and other organizations.” PERF can be reached at www.policeforum.org. 5. Kobella, Jr, Thomas R. (1986). Persuading Teachers to Reexamine the Innovative Elementary Science Programs of Yesterday: the effect of anecdotal vs data summary communications. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 23. p.437-449. 6. Hacker, Diana. (1991). The Bedford Handbook for Writers. St. Martin’s Press: New York. Copyright www.jonmshaneassociates.com -16-

© Copyright 2025